Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik, Grismer & Wood Jr & Anuar & Muin & Quah & M Guire & Brown & Tri & Thai, 2013

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/zoj.12064 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/038F8788-4E21-874C-094D-2D91FC7C282C |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov.

Tebu Mountain Slender-toed Gecko

Holotype: Adult female ( ZRC LSUHC 10904 View Materials ) collected on 2 September 2010 by Mohd Abdul Muin and Shahrul Anuar and at 2200 h from Gunung Tebu,

Terengganu, Malaysia (05°36.11′ N, 102°36.19′ E; 600 m a.sl.) GoogleMaps .

Diagnosis: Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. can be separated from all other species of Hemiphyllodactylus by the unicolour rust–orange dorsal pattern, absence of white postorbital spots, and a lamellar foot formula of 3-4-5-4. It is further separated from all other congeners by: the unique combination of a maximum SVL of 40.4 mm in females (males unknown); eight chin scales, extending transversely from unions of second and third infralabials, and the posterior margin of mental; enlarged postmental scales; five circumnasal scales; three scales between supranasals (= postrostrals); 11 supralabials; 10 infralabials; 18 longitudinally arranged dorsal scales at midbody contained within one eye diameter; 12 longitudinally arranged ventral scales at midbody, contained within one eye diameter; lamellar formula on hand 3-3-3-3; no precloacal or femoral pores in females (males unknown); postsacral mark orange and bearing anteriorly projecting arms; and ceacum and oviducts unpigmented. These characters and potentially diagnostic morphometric characters are scored across all species in Table 4.

Description of holotype: Adult female; head triangular in dorsal profile depressed, distinct from neck; lores and interorbital regions flat; rostrum relatively long (NarEye/HeadL = 0.40); prefrontal region flat to weakly concave; canthus rostralis smoothly rounded, barely discernible; snout moderate, rounded in dorsal profile; eye large; ear opening oval, small; eye to ear distance greater than diameter of eye; rostral wider than high, partially divided dorsally, bordered posteriorly by large supranasals; three internasals (= postnasals); external nares bordered anteriorly by rostral, dorsally by supranasal, posteriorly by two postnasals, ventrally by first supralabial (= circumnasals 5R,L); 11 (R,L) square supralabials tapering to below posterior margin of orbit; 10 (R,L) square infralabials tapering to below posterior margin of orbit; scales of rostrum, lores, top of head, and occiput small, granular, those of rostrum largest; dorsal superciliaries flat, rectangular, imbricate; mental triangular, bordered laterally by first infralabials and posteriorly by two large postmentals; each postmental bordered laterally by a single sublabial; four enlarged sublabials extending posteriorly to third infralabial; row of eight scales extending transversely from juncture of second and third infralabials, and contacting mental; gular scales triangular, small, granular, grading posteriorly into slightly larger, subimbricate, throat and pectoral scales, which grade into slightly larger, subimbricate ventrals.

Body somewhat elongate, dorsoventrally compressed; ventrolateral folds absent; dorsal scales small, granular, 18 scales contained within one eye diameter; ventral scales, flat, subimbricate, much larger than dorsal scales, 12 scales contained within one eye diameter; no enlarged, precloacal scales; row of enlarged, poreless femoral scales extend continuously from midway between the knee and hindlimb insertion of one leg to the other; forelimbs short, robust in stature, covered with granular scales dorsally, and with slightly larger, flat, subimbricate scales ventrally; palmar scales flat, subimbricate; all digits except digit I well developed; digit I vestigial, clawless; distal, subdigital lamellae of digits II–V undivided, angular, and U-shaped; lamellae proximal to these transversely expanded; lamellar formula of digits II–V 3-3-3-3 (R,L); five transversely expanded lamellae on digit I; claws on digits II–V well

For morphological abbreviations, see Material and methods.

Values set in bold are diagnostic from Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov.

* Zug’s (2010) concept of Hemiphyllodactylus yunnanensis , including the subspecies H. y. jingpingensis, H. y. longlingensis , H. y. yunnanensis , the Mandalay, Myanmar, population, the Cjiang Mai, Thailand, population, and the Vietnam populations.

† Zug’s (2010) concept of Hemiphyllodactylus typus , which includes the Pulau Sibu , Malaysia and Pulau, Enggano, and Indonesia populations .

developed, unsheathed; distal portions of digits strongly curved, terminal joint free, arising from central portion of lamellar pad; hindlimbs short, more robust than forelimbs, covered with slightly pointed, juxtaposed scales dorsally and by larger, flat subimbricate scales ventrally; plantar scales low, flat, subimbricate; all digits except digit I well developed; digit I vestigial, clawless; distal, subdigital lamellae of digits II–V undivided, angular, and U-shaped; lamellae proximal to these transversely expanded; lamellar formula of digits II–V 3-4-5-4 (R,L); five transversely expanded lamellae on digit I; claws on digits II–V well developed, unsheathed; distal portions of digits strongly curved, terminal joint free, arising from central portion of lamellar pad; tail relatively short, regenerated, approximately 0.8 times SVL, round in cross section; all caudal scales flat, imbricate, not forming distinct caudal segments. Morphometric data are presented in Table 4.

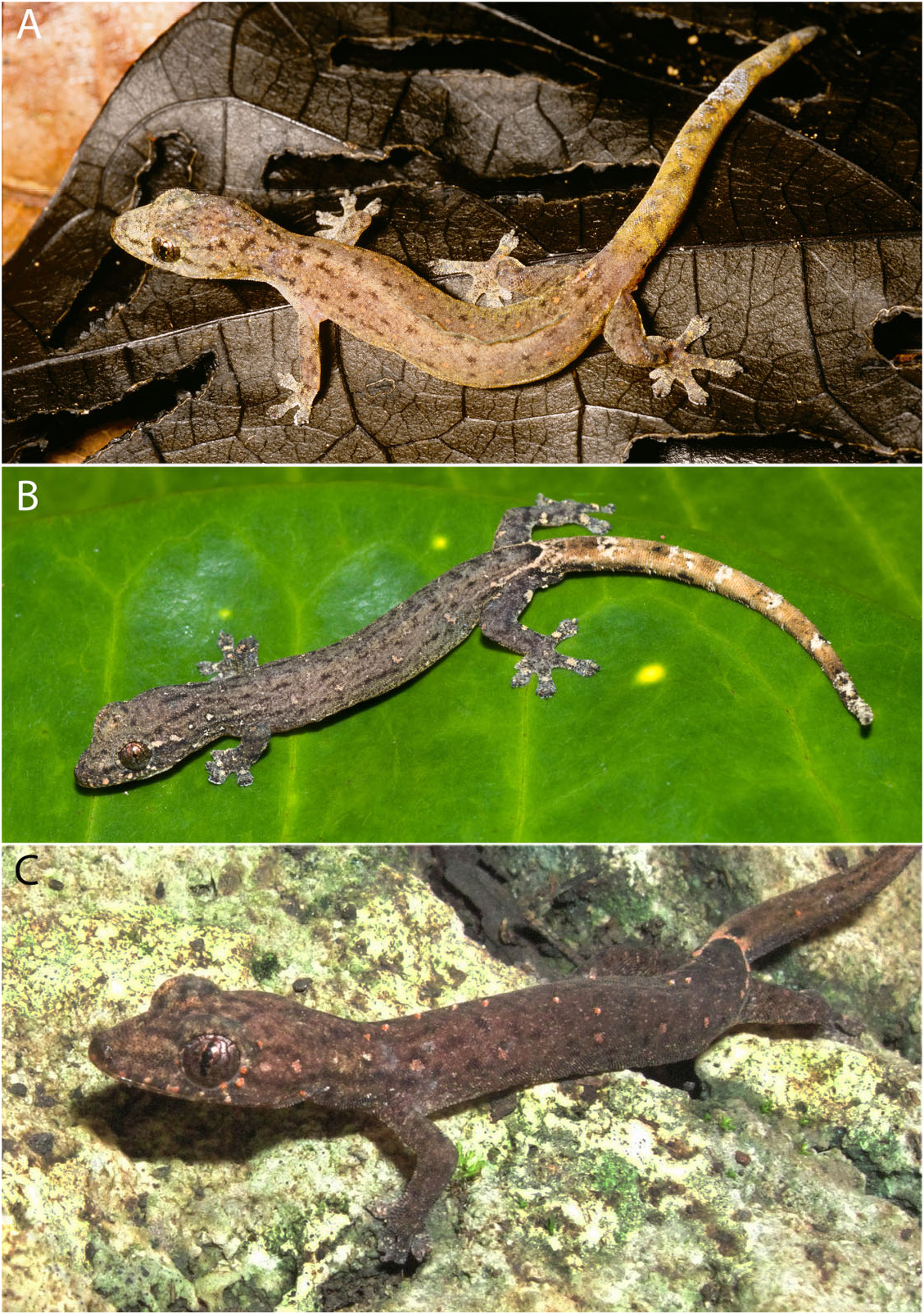

Coloration in life ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ): Top of head unicolour dull orange, transitioning into a slightly darker rust–orange coloration on body; longitudinal series of small, dark, faint, diffuse, postorbital spots; faint, dark, diffuse preorbital stripe; a slightly more prominent postorbital stripe extends to anterior margin of forearm, becoming more faint and diffuse, and wider, as it continues along ventrolateral margin of body to groin, and into postsacral region; light postsacral marking orange, bearing anteriorly projecting arms and dark medial spot; dorsal surface of limbs same colour as body; tail regenerated immediately posterior to postsacral marking, and unicolour dark brown dorsally and ventrally; distinct transition between dull or rust–orange dorsal coloration of head, body, and limbs, and immaculate, cream-coloured venter.

Distribution: Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. is known only from the type locality on Gunung Tebu, Terengganu, Peninsular Malaysia ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ), but is expected to range more widely throughout this portion of the Banjaran Timur.

Natural history: The holotype was seen at night on the leaf of a palm tree ( Licuala sp. ), approximately 1 m above the ground, along the edge of a small stream coursing through large granite boulders. During a first attempt to capture it, the lizard dropped to the ground and escaped, but was captured later that night on a different leaf of the same tree. The holotype is an adult female carrying two eggs, indicating that the reproductive season of this species extends at least through August. From only a single female, it cannot be determined if H. tehtarik sp. nov. is unisexual or bisexual.

Etymology: This species is named after a traditional Malaysian tea, Teh Tarik, which bears the rich orangish coloration of the holotype.

Comparisons: The taxonomy of Zug (2010) is used in the comparisons below. Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. differs from all other species of Hemiphyllodactylus in: a lamellar foot formula of 3-4-5-4; no white postorbital or body spots; and a unicolour dorsal body pattern. It differs further from Hemiphyllodactylus ganoklonis Zug, 2010 in having a maximum known SVL of 40.4 mm versus 34.2 mm, and from Hemiphyllodactylus margarethae Brongersma, 1931 , H. titiwangsaensis , H. typus , and H. yunnanensis by having a maximum SVL less than 46.1–49.3 mm. It differs from H. aurantiacus , H. ganoklonis , and H. insularis in having enlarged as opposed to small postmentals. Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. has five circumnasal scales that separate it from H. aurantiacus , H. ganoklonis , and H. yunnanensis having two to four, H. insularis having one to four H. margarethae having two or three, and H. titiwangsaensis having three. It is further separated from H. aurantiacus and H. margarethae in having 18, as opposed to 11–17, dorsal scales, and from H. titiwangsaensis in having 12, as opposed to between seven and nine, ventral scales. Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. has a lamellar hand formula of 3-3-3-3, which separates it from H. aurantiacus having 2-2-2-2, H. ganoklonis having 3-4-4-3, H. margarethae having 4-4-4-4, and H. titiwangsaensis and H. typus having 3-4-4-4. From H. harterti , H. tehtarik sp. nov. differs in having five transversely expanded subdigital lamellae beneath digits I on the hands and feet, as opposed to having three on digit I of the hand and four on digit I of the foot. It can be separated further from H. harterti in having three cloacal spurs as opposed to one, and from H. yunnanensis , which has between zero and two cloacal spurs. Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. has an orangish postsacral marking, which separates it from all other species except H. aurantiacus and most H. typus . The postsacral markings in H. tehtarik sp. nov. bear anteriorly projecting arms that differentiate it from H. aurantiacus , H. harterti , H. titiwangsaensis , and H. yunanensis . The caecum and gonadal tracts of H. tehtarik sp. nov. are unpigmented, further differentiating them from H. aurantiacus , H. ganoklonis , some H. margarethae , and H. typus . A number of morphometric ratios of other species of Hemiphyllodactylus differ discretely from the corresponding ratio in H. tehtarik sp. nov; however, having a sample size of one does not allow for observing the range of ratios that must exist, and therefore they are not considered definitive at this point, but they are illustrated in Table 4.

Phylogenetic relationships: Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik sp. nov. is part of an upland clade of species endemic to the mountain systems of Peninsular Malaysia ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). The basal member of this clade, H. harterti , occurs in the westernmost range, the Banjaran Bintang, whereas H. tehtarik is known only from an outlying section of the eastern ranges (referred to collectively as the Banjaran Timur), but is

the sister species of H. larutensis from the Banjaran Bintang.

Remarks and comments: There have been no published herpetofaunal surveys from the extensive mountain systems of north-eastern Peninsular Malaysia (Banjaran Timur), save for Boulenger (1908) and Dring (1979). Thus, the discovery of a new species from a widespread lineage of small, secretive geckos from a remote unexplored upland area in a region in which nearby mountain ranges are rich in lizard diversity ( Grismer, 2011a) is not surprising. Nonetheless, it further underscores our lack of knowledge concerning the herpetological composition of the Banjaran Timur in general, and Gunung Tebu in particular. The fact that our expedition was able to collect three new species of lizards, three new species of frogs, and a new species of snake in two nights (see Grismer et al., 2013; E. Quah, unpubl. data) is a clear indication that sampling from this mountain is far from complete. Given the high degree of herpetological endemism and diversity seen in the other two major upland systems of Peninsular Malaysia, the Banjaran Bintang and Banjaran Titiwangsa (see Grismer & Pan, 2008; Grismer et al., 2010b; Grismer, 2011a and references therein), and what relatively few species are know from the upland areas of the Banjaran Timur (see Boulenger, 1908; Dring, 1979), we can estimate that only a small fraction of this herpetofauna is known. Effective management and conservation strategies can only be accomplished once this herpetofauna is more fully understood.

Some (i.e. Dayrat, 2005) have grave concerns about descriptions of new species based on only a single specimen, and posit that this should ‘never’ be reported because such a description cannot take into account infraspecific variation that could potentially preclude its specific recognition. Although this is a theoretically noble notion, it is counterproductive in reality, and might impede biodiversity studies in general and taxonomy in particular, given that recent estimates show that 19% of all new vertebrate species described between 2000 and 2010 were based on a single specimen ( Lim, Balke & Meier, 2012). In the context of the monographic revision of Hemiphyllodactylus by Zug (2010) and the molecular data presented here, it is clear the morphology, colour pattern, and genetics of H. tehtarik lie well outside that of the known species boundaries of all other Hemiphyllodactylus , and would thus require a significant amount of contradictory evidence to provide a robust, scientific reason for not describing H. tehtarik sp. nov. If future work proves that this name (i.e. hypothesis about the relationships of individuals discovered in the future) is falsified and H. tehtarik is a junior synonym of some other taxon, then it is the very testability of the name that makes it a legitimate hypothesis ( Valdecasas, Williams & Wheeler, 2008).

The convoluted taxonomic history of H. harterti has accumulated from a sequence of compounding errors including: (1) the imprecise designation of its type locality ( Werner, 1900); (2) the fact that two names, H. harterti and Hemiphyllodactylus larutensis ( Boulenger, 1900) were available for different populations from the Banjaran Bintang for well over a century; (3) various authors (i.e. Chan-ard et al., 1999) indiscriminately applying both names to a single population (Cameron Highlands) from an entirely different mountain range (the Banjaran Titiwangsa); (4) erroneous reports ( Bauer & Günther, 1991) as to what Boulenger (1912) actually considered the type locality of H. harterti (see discussion in Grismer, 2011a: 499); (5) colour descriptions of H. harterti based on the wrong species ( Zug, 2010: 29); and (6) no recent material of either species being available for morphological and molecular analyses since 1900. We examined two specimens recently collected from Bukit Larut ( LSUHC 10383–84) that are consistent with the description of H. harterti ( Werner, 1900) and with images of the holotype from Gunung Hijau ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ) and nine specimens recently collected from Bukit Larut ( LSUHC 11293–96, 11298–99, 11542, 11591–92) that match the description and images of the holotype of H. larutensis ( Boulenger, 1900; Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). These specimens provide the basis for more complete descriptions of both species [commensurate with those descriptions of other species of Hemiphyllodactylus following Zug (2010)] as well as a molecular analysis in order to determine their phylogenetic placement within the genus—in particular their relationships to each other and other upland populations from Peninsular Malaysia.

Boulenger (1912) noted that the imprecise type locality designation of ‘Melacca’ by Werner (1900) for H. harterti essentially referred to the entire west coast of the Thai-Malay Peninsula and noted that the specimen collected by Ernest J. O. Hartert came from ‘Gunong’ (= Gunung) Inas, a peak in the northern portion of the Banjaran Bintang. Shortly after Werner’s (1900) description, Boulenger (1900) described H. larutensis from the Larut Hills (= Bukit Larut)—another upland locality approximately 40 km south of Gunung Inas in the same mountain range— and later indicated ( Boulenger, 1912) that these two populations were probably conspecific. Kluge (1991, 2001), by implication, was the first to apply the nomen H. harterti to both populations and was followed by Grismer et al. (2010b) who listed a complete synonymy of names. Zug (2010) was the first in over a century to examine the holotype of H. larutensis and by comparing it to a series of photographs of the holotype of H. harterti , he indicated the two species were conspecific. A morphological ( Table 5; Fig. 5 View Figure 5 and see below) and molecular analysis of the newly collected material of both species from Bukit Larut confirms that not only are they different species, they are not even each others’ closest relatives, in that H. larutensis is the sister species of H. tehtarik —an upland species across three different mountain ranges 175 km to the east ( Figs 1 View Figure 1 , 4 View Figure 4 ). Additionally, H. harterti and H. larutensis have a sequence divergence of 20.6% despite being sympatric.

Werner’s (1900) short description of the adult female holotype of Hemiphyllodactylus harterti (ZMB 1360) does not unequivocally diagnose it from Boulenger’s (1900) slightly better description of the adult male holotype of H. larutensis ( BM 1901.3.20.2). Nonetheless, H. harterti can be separated from H. larutensis on the basis of a number of characteristics observable on a series of photographs of the holotype ZMB 1360 ( LSUHC 8080–86) that were confirmed on specimens LSUHC 10383–84. The body stature of H. harterti is more robust than that of H. larutensis ( Fig. 5B–F View Figure 5 ) and it has a smaller adult SVL. Adult male (as determined by gonadal inspection) H. harterti are 33.2–34.7 mm SVL versus 42.7–43.1 mm in adult male H. larutensis . The female holotype of H. harterti measures 42 mm SVL versus 44.3–52.2 mm for adult female H. larutensis . Male H. larutensis have 27–36 femoroprecloacal pores and two or three cloacal spurs whereas male H. harterti have 44 or 45 femoroprecloacal pores and a single cloacal spur. The subcaudal scales of the holotype and recently collected material of H. harterti are nearly twice the size as the dorsal caudal scales whereas in H. larutensis dorsal and subcaudal scales are the same size. Werner (1900) did not describe the colour pattern of H. harterti but mentioned it matched that of L. lugubris which Zug (2010) interpreted to mean having dark wavy crossbars. The only colour photograph of a living specimen of H. harterti appeared in Grismer, 2011a, which showed it to have a generally spotted dorsum (that is only vaguely visible on the faded holotype) as opposed to the generally unicolour dorsal pattern of H. larutensis ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The colour photograph of the unicoloured specimen in Zug (2010: fig. 11c) from Bukit Larut labelled as H. harterti is actually H. larutensis . Zug (2010: 29) used a colour photograph of a different nearly unicoloured specimen of H. larutensis appearing in Chan-ard et al. (1999: 130) to form the basis of his colour pattern description of H. harterti . Boulenger (1900) noted that the caudal colour pattern of H. larutensis was ‘yellowish with... a vertebral series of small blackish spots widely sepa- rated from each other’. This pattern is still clearly visible on the holotype and occurs in the newly collected specimens ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ) whereas the caudal pattern of H. harterti consists of randomly arranged spots that are visible on the holotype and the specimens from Bukit Larut ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The base of the sacral marking in H. larutensis is bordered by a medial, dark, triangular marking whereas in H. harterti the base is bordered by a pair of dark lateral blotches ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ).

The following redescriptions of H. harterti and H. larutensis are based on two adult males ( LSUHC 10383–84 View Materials ) and one adult female ( ZMB 1306 ) of the former and four adult males ( BM 1901.3.20.2; LSUHC 11298 View Materials , 11591–92 View Materials ) and six adult females ( LSUHC 11293–96 View Materials , 11299 View Materials , 11542 View Materials ) of the latter. A number of the recently collected specimens from Bukit Larut were photographed shortly after capture ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). For comparative purposes, the following redescriptions are generally styled after those of other Hemiphyllodactylus ( Zug, 2010) .

Redescription of Hemiphyllodactylus harterti ( Werner, 1900)

Head triangular in dorsal profile depressed, distinct from neck; lores and interorbital regions flat; rostrum moderate in length; prefrontal region flat; canthus rostralis smoothly rounded, barely discernible; snout moderate, rounded in dorsal profile; eye large; ear opening oval, small; eye to ear distance greater than diameter of eye; rostral wider than high, partially divided dorsally, bordered posteriorly by large supranasals; two or three internasals (= postnasals); external nares bordered anteriorly by rostral, dorsally by supranasal, posteriorly by two large postnasals, ventrally by first supralabial (= circumnasals 5R,L); ten or 11 square supralabials tapering to below posterior margin of orbit; ten or 11 square infralabials tapering to below posterior margin of orbit; scales of rostrum raised, juxtaposed; scales of lores, top of head, and occiput small, granular, smaller than those of rostrum; dorsal superciliaries flat, rectangular, imbricate; mental triangular, bordered laterally by first infralabials and posteriorly by two large postmentals; each postmental bordered laterally by one or two sublabials; two enlarged sublabials extending posteriorly to second infralabial; row of eight scales extending transversely from juncture of second and third infralabials and contacting mental; gular scales triangular small, granular, grading posteriorly into slightly larger, subimbricate, throat and pectoral scales which grade into slightly larger, subimbricate ventrals.

Body somewhat stout, dorsoventrally compressed; ventrolateral folds absent; dorsal scales small, granular, 14–19 scales contained within one eye diameter; ventral scales, flat, subimbricate much larger than

For morphological abbreviations, see the Material and methods.

dorsal scales, ten–14 scales contained within one eye diameter; no enlarged, precloacal scales; row of 44 or 45 enlarged, pore-bearing femoral scales extend continuously from midway between the knee and hindlimb insertion of one leg to the other; forelimbs short, robust in stature, covered with flat, subimbricate scales dorsally and ventrally of similar size; palmar scales flat, subimbricate; all digits except digit I well developed; digit I vestigial, clawless; distal, subdigital lamellae of digits II–V undivided, angular and U-shaped; lamellae proximal to these transversely expanded; lamellar formula of digits II–V 3-3-3-3; three transversely expanded lamellae on digit I; claws on digits II–V well developed, unsheathed; distal portions of digits strongly curved, terminal joint free, arising from central portion of lamellar pad; hind limbs short, more robust than forelimbs, covered with flat subimbricate scales dorsally and ventrally of similar size; plantar scales low, flat, subimbricate; all digits except digit I well developed; digit I vestigial, clawless; distal, subdigital lamellae of digits II–V undivided, angular and U-shaped; lamellae proximal to these transversely expanded; lamellar formula of digits II–V 3-3-4-3; four transversely expanded lamellae on digit I; claws on digits II–V well developed, unsheathed; distal portions of digits strongly curved, terminal joint free, arising from central portion of lamellar pad; tail relatively short, not forming distinct caudal segments; original tail ( LSUHC 10384, ZMB 1306) round in cross-section, covered with flat imbricate scales, subcaudal scales nearly twice the size of dorsal caudals; regenerated tail ( LSUHC 10383) more flat in cross-section covered with flat imbricate scales, and bearing a weak ventrolateral fringe of scales, subcaudal scales slightly larger than dorsal caudals. Morphometric and mensural data are presented in Table 5.

Coloration ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ): The ground colour of the dorsal surface of the head, body, limbs, and tail is light brown and overlain with semi-regularly arranged longitudinal rows of diffuse, irregularly shaped darker dorsolateral markings; light and dark speckling occurs on the top of the head; there is a faint, irregular dark, preorbital and postorbital stripe bordered dorsally by a faint, beige line or a series of diffuse blotches; light, diffuse, irregularly shaped markings occur on the back and extend from the nape to the base of the tail; a diffuse, barely discernible postsacral marking begins at the base of the tail with paired light coloured blotches edged anteriorly by dark markings and anteriorly projecting arms extend to just beyond the anterior margin of the hind limb insertions; both the regenerated and original tails have a lighter base colour than the dorsum and are covered with semi-longitudinally arranged diffuse small, dark, irregularly shaped blotches; faint, dark, diffuse markings occur on the limbs much like the body; there are no distinct, large, white to orange spots on the digits; all the ventral surfaces are beige with each scale bearing 0–2 small black stipples.

Redescription of Hemiphyllodactylus larutensis ( Boulenger, 1900)

Head triangular in dorsal profile depressed, distinct from neck; lores and interorbital regions flat; rostrum moderate in length; prefrontal region flat; canthus rostralis smoothly rounded, barely discernible; snout moderate, rounded in dorsal profile; eye large; ear opening oval, small; eye to ear distance greater than diameter of eye; rostral wider than high, partially divided dorsally, bordered posteriorly by large supranasals; three internasals (= postnasals); external nares bordered anteriorly by rostral, dorsally by supranasal, posteriorly by one or two large postnasals, ventrally by first supralabial (= circumnasals); nine–11 square supralabials tapering to below posterior margin of orbit; seven–ten square infralabials tapering to below posterior margin of orbit; scales of rostrum raised, juxtaposed; scales of lores raised, larger than those of rostrum; scales of top of head and occiput small, granular, smaller than those of rostrum; dorsal superciliaries flat, rectangular, subimbricate; mental triangular, bordered laterally by first infralabials and posteriorly by two large postmentals; each postmental bordered laterally by one or two sublabials; two or three enlarged sublabials extending posteriorly to second infralabial; row of six–nine scales extending transversely from juncture of second and third infralabials and contacting mental; gular scales triangular small, flat, grading posteriorly into slightly larger, subimbricate, throat and pectoral scales which grade into slightly larger, subimbricate ventrals.

Body somewhat elongate, dorsoventrally compressed; ventrolateral folds absent; dorsal scales small, granular, 13–20 scales contained within one eye diameter; ventral scales, flat, subimbricate much larger than dorsal scales, six–13 scales contained within one eye diameter; no enlarged, precloacal scales; row of 27–36 enlarged, pore-bearing femoral scales extend continuously from midway between the knee and hind limb insertion of one leg to the other; forelimbs short, robust in stature, covered with flat, subimbricate scales dorsally and ventrally of similar size; palmar scales flat, subimbricate; all digits except digit I well developed; digit I vestigial, clawless; distal, subdigital lamellae of digits II–V undivided, angular and U-shaped; lamellae proximal to these transversely expanded; lamellar formula of digits II–V 2-4-4-3, 3-3-3-3, 3-4-4-3, or 3-4-4-4; three transversely expanded lamellae on digit I; claws on digits II–V well developed, unsheathed; distal portions of digits strongly curved, terminal joint free, arising from central portion of lamellar pad; hindlimbs short, more robust than forelimbs, covered with flat subimbricate scales dorsally and ventrally of similar size; plantar scales low, flat, subimbricate; all digits except digit I well developed; digit I vestigial, clawless; distal, subdigital lamellae of digits II–V undivided, angular and U-shaped; lamellae proximal to these transversely expanded; lamellar formula of digits II–V 3-3-4-3, 3-4-4-4, 3-5-5-4, or 4-5-5-5; four transversely expanded lamellae on digit I; claws on digits II–V well developed, unsheathed; distal portions of digits strongly curved, terminal joint free, arising from central portion of lamellar pad; tail relatively short, not forming distinct caudal segments; original and regenerated tail round in cross-section, covered with flat imbricate scales, subcaudal scales same size as dorsal caudals. Morphometric and mensural data are presented in Table 5.

Coloration ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ): The ground colour of the dorsal surface of the head, body, limbs, and tail is dark brown to tan and generally unicolour except for very faint, diffuse, irregularly shaped darker dorsolateral markings; faint, diffuse dark, preorbital and postorbital stripe; a series of small postocular dots extend onto neck; postsacral marking begins at the base of the tail with a medial triangular dark marking; orangish coloured anteriorly projecting arms extend to just beyond the anterior margin of the hind limb insertions; both the regenerated and original tails are orangish in colour bearing a series of dark, widely spaced vertebral spots, spots sometimes form a faint vertebral line; limbs immaculate; there are no distinct, large, white to orange spots on the digits; and all the ventral surfaces are beige with each scale bearing zero–four small black stipples.

Hemiphyllodactylus titiwangsaensis Hemiphllodactylus titiwangsaensis is known from three populations within the Banjaran Titiwangsa of Peninsular Malaysia: a northern population from the Cameron Highlands, Pahang, and two southern populations, one from Fraser’s Hill, and another from Genting Highlands, Pahang ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). Zug’s (2010) description of H. titiwangsaensis included only specimens from the Cameron Highlands, although he mentioned the occurrence of this species at Fraser’s Hill, but did not note its presence from the Genting Highlands ( Smedley, 1932). Grismer (2011a) alluded to the differences between the northern and the two southern populations, which is well-supported in the molecular analysis ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). This cladogenic split along the Banjaran Titiwangsa is also seen in the sister species Cyrtodactylus trilatofasciatus Grismer et al., 2012a and Cyrtodactylus australotitiwangsaensis Grismer et al., 2012a , and is a common pattern beginning to emerge in a number of other taxa (L. L. Grismer, P. L. Wood, E. S. H. Quah, S. Anuar, M. A. Muin & A. Norhayati, unpubl. data). The two lineages of Hemiphyllodactylus are separated by approximately 85 km and have a sequence divergence of 12.4–12.8%, strongly suggesting that gene flow between them does not exist. The sequence divergence within the southern clade between the sister lineages from Fraser’s Hill and the Genting Highlands is 3.5%, and occurs over a distance of approximately 35 km ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). Based on the sequence divergence and discrete morphological differentiation (L. Grismer, unpubl. data), we restrict the distribution of H. titiwangsaensis to the Cameron Highlands and, at this juncture, consider the populations from Fraser’s Hill and the Genting Highlands as the CCS H. sp. nov. 1, which is currently being described.

The typus group

Zug (2010) speculated that Hemiphyllodactylus was composed of two ‘subclades’ (for which no explicit data of monophyly for either were presented), based on generally non-discrete overlapping morphological characters. He proposed the typus species group to contain Hemiphyllodactylus auarntiacus (Beddome, 1870) , H. ganoklonis , H. insularis , H. typus , and populations in Borneo, and the yunnanensis species group to contain at least H. harterti , H. margarethae , and H. yunnanensis . The placement of other taxa were not mentioned. The genetic data presented here do not support this division, in that multiple members of Zug’s (2010) proposed groups are embedded within each other ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). Given the lack of unequivocal morphological support for these subclades and no evidence for their monophyly, we elect to follow a more robust partitioning of Hemiphyllodactylus based on the deep divergence (28.9%) indicated by the molecular evidence. The typus group as constructed here is composed of seven distinct strongly supported clades that encompass the nominal taxa H. aurantiacus , H. ganoklonis , H. insularis , H. typus , and H. yunnanensis , including the subspecies H. y. dushanensis , H. y. jinpingensis , H. y. longlingensis , and H. y. yunnanensis ( Zhou et al., 1981; Zug, 2010). Samples of H. margarethae from Sumatra, Indonesia, were unavailable, and we will not speculate about which group it belongs to. With the exclusion of the unisexual H. typus , this group extends from southern India and Sri Lanka, across Indochina, to Hong Kong. Although the relationships among the four wellsupported basal lineages (A–D) composing the typus group remain unresolved, the considerable degree of phylogenetic substructuring within and among the seven clades that these basal lineages comprise is well supported ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ), and the taxonomic implications of this substructuring are discussed below.

Taxonomy of the typus group

Zug (2010: fig. 16) provisionally divided H. yunnanensis into a northern upland group ( H. yunnanensis ) from southern China and adjacent northern Southeast Asia, and a southern lowland group (‘ H. yunnanensis ’) from Southeast Asia and Hong Kong, although no clear morphological differences were presented in support of either group. The genetic data presented here and those of Heinicke et al. (2011b) do not support this division. Hemiphyllodactylus yunnanensis s.l. is polyphyletic with respect to lineages from northern Thailand, northern Myanamar, southern Laos, and central Vietnam, as well as H. aurantiacus from southern India ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ).

Clade 1: This lineage is composed of an insular population from Pulau Sibu of the Seribuat Archipelago, Peninsular Malaysia, and its sister population from Pulau Enggano, off the south-west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, and both are currently recognized as H. typus ( Wood et al., 2004; Grismer et al., 2006; Zug, 2010; Grismer, 2011a, b). The Pulau Sibu population (LSUHC 5797; Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ) is not H. typus because the only known specimen is a male and H. typus is parthenogenetic. Unfortunately, the specimen was lost in transit. Because this specimen is a male and is genetically distinct from all other congeners, we recognize the Pulau Sibu population as CCS H. sp. nov. 2. We examined two specimens recently collected from Pulau Enggano (MVZ 239345–46, Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ), and conclude that they are not H. typus based on scalation and that MVZ 239345 is a male. Additionally, this population cannot be ascribed to H. margarethae from Sumatra (with a possible occurrence on Pulau Nias off the west coast of Sumatra; Zug, 2010) in that the male specimen (MVZ 239345) has a total of 42 continuous femoral and precloacal pores, whereas H. margarethae has a total of 29 pores, and the femoral and precloacal series are discontinuous ( Zug, 2010). We consider the Pulau Enggano population as CCS H. sp. nov. 3. The peculiar biogeographical pattern of species from islands in the Seribuat Archipelago being more closely related to species on islands in the Sunda Shelf (hundreds of kilometres to the south), as opposed to species from Peninsular Malaysia, less than 40 km to the west, is not uncommon (for a list of species across a broad taxonomic range, see Grismer et al., 2006), and is a pattern that is continuing to emerge as more phylogenies are developed.

Clade 2: This clade is composed of two sister lineages: a weakly supported Philippine and Pulau Ngercheu lineage, and a strongly supported lineage containing a population from Mindanao, Philippines, and populations of H. typus extending from Peninsular Malaysia to Fiji. The basal species of clade 2 are H. insularis from Zamboanga City Province, Mindano ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ) and H. ganoklonis from Pulau Ngercheu, respectively. The sister populations from Mount Lantoy, Cebu Island, and from Pulaui Island each represent new species, as neither is embedded within any other species on the tree ( Figs 1 View Figure 1 , 8 View Figure 8 ), and have sequence divergences of 13.9–17.5% and 16.6–21.9%, respectively, from the other species of clade 2. The morphology of the Cebu Island specimen (KU 331843) is unique and does not align with any known taxon ( Zug, 2010), and as such it is considered here as CCS H. sp. nov. 4. We did not examine material from Pulaui Island, and thus consider it UCS H. sp. nov. 5. The H. typus lineage contains a basal population from Mindanao that we consider as UCS H. sp. nov. 6, in that it shows reasonable separation (3.0% sequence divergence) from the other H. typus specimens, even though the specimens examined (KU 314090–91) are superficially similar to H. typus and require further study. Although only four specimens of the widely distributed unisexual H. typus were sampled, the samples covered a distance of approximately 9000 km from Penang Island, Peninsular Malaysia, in the west to Suva, Fiji, in the east, and showed a sequence divergence of only 0.1%, which is not surprising given this species is parthenogenetic and a likely human commensal. We consider this as additional support to our hypothesis that KU 314090–91 from Mindano are not H. typus , even though they have less than a 5.8% sequence divergence from H. typus . Zug (2010) reports a bisexual population of H. typus from northeastern Borneo in need of further study.

Clade 3: The phylogeny indicates H. yunnanensis (sensu Zug, 2010; clades 3–7) is polyphyletic with respect to H. aurantiacus and at least four undescribed species (see below), even though it is composed of a number of lineages with considerable and well-supported substructuring ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). Zug (2010) considered H. y. longlingensis and H. y. jinpingensis (and presumably H. y. dushanensis , although it was not mentioned) as synonyms of a ‘monotypic’ (sensu Zug, 2010) H. yunnanensis , based on what he considered (without examination) to be a size continuum between two different states (ranging from ‘barely’ enlarged to ‘strongly’ enlarged) of the postmental and chin scales (contra Zhou et al., 1981). The phylogeny ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ), however, indicates that H. y. jinpingensis and H. y. longlingensis form distinct lineages that are not even each other’s closest relatives, in that H. y. longlingensis forms a clade with populations from Central Myanmar and northwestern Thailand, which are shown below to be distinct species themselves (i.e. not H. yunnanensis sensu Zug, 2010 ). Zhou et al. (1981) separated these two subspecies on the basis of the former having subdigital scansor formulae of 3-4-4-4 on the hand and 4-5-5-5 on the foot, as opposed to 3-3-3-3 on the hand and 3-4-4-4 on the foot in the latter, and they have a mean sequence divergence between them of 18.6% ( Table 3). Furthermore, based on Zhou et al. (1981), these non-reticulating lineages come from disjunct upland populations in different mountain ranges that extend for approximately 1200 km across southern China, from Longling County, Yunnan Province, in the west to Dayaoshan, Guangxi Province, in the east ( Zhou et al., 1981; Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). One outlying individual of H. y. longlingensis (FJ971049.1) does not group with other H. y. longlingensis specimens, but instead forms a distant (18.4% sequence divergence) sister lineage relationship with H. y. jinpingensis ( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). Unfortunately we were unable to examine this specimen or to determine from the authors its provenance, and thus we leave its species status as insertae sedis. With the exception of this outlying individual, recognizing the subspecies of H. yunnanensis as species-level taxa is more consistent with the genetic, morphological, and biogeographic data, and does not misrepresent their evolutionary history by recognizing a polyphyletic H. yunnanensis .

Clade 4: Clade 4 is the sister lineage to clade 3, and is composed of a basal lineage from Chiang Mai, Thailand, and its sister lineages from Pyin-Oo-Lwin, Mandalay Division, Myanmar, and H. longlingensis from southern China ( Zhou et al., 1981; Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). Neither the Chiang Mai nor Mandalay populations are phylogenetically imbedded within H. longlingensis , to which they are related, or imbedded within H. yunnanensis , with which they are currently considered conspecific ( Zug, 2010). Additionally, they bear substantial sequence divergences between them and the other lineages of clades 3 and 4 (18.6– 18.8%; Table 6). We have examined nine specimens (Appendix) from Chiang Mai, and have found that they are morphologically distinct from all other Hemiphyllodactylus (L. L. Grismer, P. L. Wood, M. Cota, unpubl. data), and recognize them here as CCS H. sp. nov. 7 ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ). We have examined only colour photos of a specimen from Mandalay ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ), but given its phylogenetic position within clade 4 and its 13.5% sequence divergence from its sister species H. longlingensis , we consider this population as UCS H. sp. nov. 8.

Clade 5: The species status of H. aurantiacus from southern India and Sri Lanka ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 10 View Figure 10 ) is well supported in the phylogeny, and corroborates Zug’s (2010) continued recognition of this taxon as a species-level lineage (contra Smith, 1935), based on morphology. A specimen catalogued as H. yunnanensis (FMNH 258695) from Pakxong District, Champasak Province, in southern Laos, and recognized by Zug (2010) as ‘ H. yunnanensis ’ is the sister lineage to H. aurantiacus ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). Based on the considerable sequence divergence (23.1%) between these lineages, the significant distributional gap between southern India and Champasak, Laos (∼ 3000 km; Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ), and the distinct morphology of this population (B. L. Stuart, unpubl. data), we consider this lineage as CCS H. sp. nov. 9, and we predict that geographically intervening species within this clade will eventually be discovered. Heinicke et al. (2011b) have previously considered this population to be a distinct species.

Clade 6: Clade 6 is composed of a basal lineage from Ba Na-Nui Chua Nature Reserve, Hoa Vang District, Da Nang City, in central Vietnam (‘ H. yunannensis ’; Zug, 2010), and the sister species H. zugi from Vinh Phuc Province in northern Vietnam ( Zug, 2010) and H. dushanensis from Guizhou Province in southern China ( Nguyen et al. 2013; Zhou et al., 1981; Figs 1 View Figure 1 , 2 View Figure 2 ). Based on morphology (V. T. Ngo, L. L. Grismer, H. Pham, P. L. Wood, unpubl. data), the Ba Na-Nui Chua Nature Reserve population ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ) cannot be ascribed to any known species of Hemiphyllodactylus , and it has a 16.7% sequence divergence from other lineages in clade 6. Thus, we consider it here to be CCS H. sp. nov. 10.

Clade 7: Clade 7 comprises H. yunnanensis s.s., and is what Zhou et al. (1981) considered to be H. y. yunnanensis . The phylogeny ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ) indicates that there is considerable substructuring within this lineage, with perhaps as many as five additional species. We were unable to ascertain the exact localities of the specimens in Figure 1 View Figure 1 , nor did we examine material from southern China. Unlike other species of Hemiphyllodactyls, H. yunnanensis s.s. still contains a large number of undescribed species scattered throughout the vast fragmented uplands of southern China.

| ZRC |

Zoological Reference Collection, National University of Singapore |

| LSUHC |

La Sierra University, Herpetological Collection |

| BM |

Bristol Museum |

| ZMB |

Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (Zoological Collections) |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Hemiphyllodactylus tehtarik

| Grismer, L. Lee, Wood Jr, Perry L., Anuar, Shahrul, Muin, Mohd Abdul, Quah, Evan S. H., M Guire, Jimmy A., Brown, Rafe M., Tri, Ngo Van & Thai, Pham Hong 2013 |

Hemiphyllodactylus

| Grismer & Wood Jr & Anuar & Muin & Quah & M Guire & Brown & Tri & Thai 2013 |

Cyrtodactylus trilatofasciatus

| Grismer 2012 |

Cyrtodactylus australotitiwangsaensis

| Grismer 2012 |

Hemiphyllodactylus titiwangsaensis

| Zug 2010 |

typus

| Bleeker 1860 |