Resomia similis ( Margulis, 1977 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.174440 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5688263 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/038F8C6C-FFC9-D427-6314-FAFC4B0BA864 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Resomia similis ( Margulis, 1977 ) |

| status |

|

Resomia similis ( Margulis, 1977) View in CoL

Diagnosis: Very young nectophores usually with distinct lateral digitate processes. Bracts with relatively large rounded distal facet, often bearing a lateral cusp. Bracteal canal ends below cluster of nematocysts on slightly swollen process on upper side of bract. Palpons with cluster of nematocysts at distal tip.

Material examined: Fragments believed to represent parts of a single specimen, collected by a sediment trap; parts appeared in four out of five sequential samples, each open for ten days, over the period 5th January to 24th February 1999. The sediment trap was located at a depth of 442 m at 52°37.18’S, 174°08.75’E over a water depth of 2592 m on the Campbell Plateau, south of New Zealand. The first sample contained the posterior end of the siphosome; the second the main bulk of the specimen; while loose gastrozooids and tentacles were found in the 4th and 5th samples of the sequence. I am extremely grateful to Dr Dennis Gordon of NIWA, Wellington, New Zealand, for sending this material to me.

Description:

Pneumatophore: The pneumatophore ( Fig. 12 A View FIGURE 12. A ) was very distinctive and measured 5.5 mm in height and 2.1 mm in diameter. There was a group of darker cells at its apex, which may indicate that it was pigmented in life, and eight external ribs that petered out toward the apex. The pneumatosaccus was restricted to a small volume in the apical half. It was not clear, however, how much distortion occurred due to the expansion of gas during retrieval.

A pneumatophore ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12. A B), in poor condition, was found amongst Totton’s material in the Natural History Museum from Discovery St. 1913 (See Table 1 View TABLE 1 for station details). No external ribs could be discerned, and the pneumatosaccus occupied almost threequarters of the total length. However, the overall structure and particularly the region below the pneumatosaccus showed some similarities with the pneumatophore found in the sediment trap material. The possibility that this pneumatophore may belong to Resomia similis is discussed below.

Nectosome: The young nectophoral buds were attached below the pneumatophore on the ventral side of the stem ( Fig. 12 A View FIGURE 12. A ).

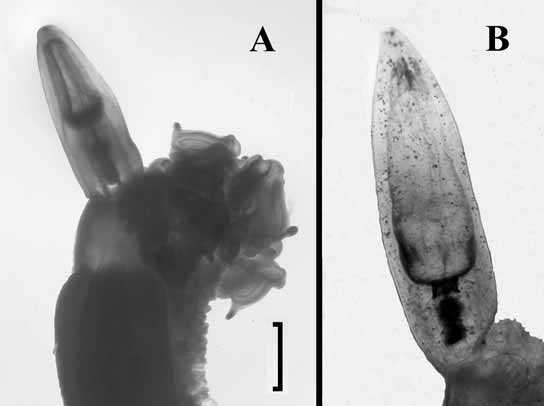

Nectophore: Unfortunately no nectophores other than those at a very early growth stage were found with the material examined. Nonetheless, these very young nectophores are of interest as they clearly showed a difference from those of Resomia convoluta in that they usually bore digitate processes projecting laterally from the region of the axial wings ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 ). These nectophores measured 2.4–2.7 mm in length, and from 2.8 to 3.7 mm in maximum width, dependent on the presence or absence of the digitate processes. Even at this stage it can be seen that the radial canals are straight and that both ascending and descending pallial canals are present. The youngest nectophores, still attached to the stem ( Fig. 12 A View FIGURE 12. A , Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 – centre), bore a digitate process on both sides, but as they enlarged these processes were gradually resorbed to a point where there was only a lateral swelling on one side ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 – left). Unfortunately this process of resorption could not be followed further because of the absence of larger nectophores in the sample.

Siphosome:

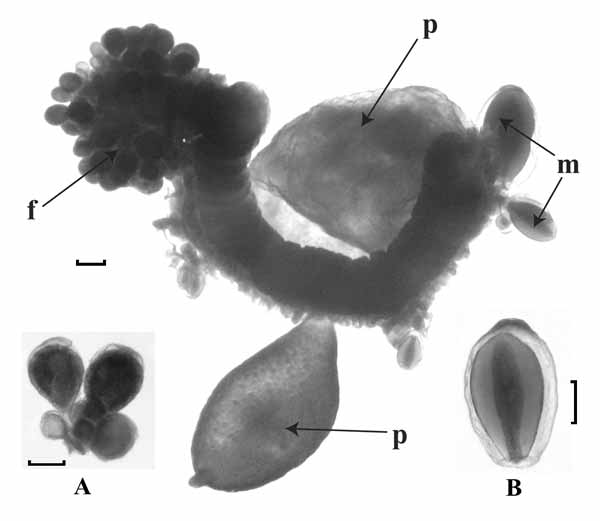

Bract: ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 ). The bracts measured up to 10 mm in length and 6 mm in width, with the largest ones being very flimsy. There was a transverse ridge running across the upper side of the bract between two, more or less pronounced, lateral cusps. This ridge, which separated the proximal and distal parts of the bract, had a variable position, but most often it occurred at the mid-length of the bract, or slightly more distally. At all stages of growth it partially overhung the distal facet, and usually extended to the lateral margins of the bract. The ridge occasionally had a ragged appearance, particularly in the younger bracts. Proximal to the ridge the width and depth of the bract tapered gradually so that, in the oldest bracts, the proximal end formed a rounded point. The distal facet was almost hemispherical in outline, and rapidly lost depth distal to the transverse ridge. On about a third of the bracts there was a distinct lateral cusp on one side ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 C).

On mature bracts ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 C) the proximal end of the bracteal canal began on its upper side and then extended for some distance along one side before passing over onto the lower side at the proximal end of the bract. This extension was usually less marked in the younger bracts ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 B). In the youngest bracts ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 A) the walls of the canal were greatly thickened by a honeycomb of endodermal cells. The canal itself, however, was expanded only in its mid-region. As the bracts matured the walls of the canal narrowed, and in the most mature ones they were only slightly thickened in the mid-region, being relatively thin both distally, as it passed up through the mesogloea, and proximally.

The distal end of the canal terminated below a small cluster of nematocysts ( Fig. 15 View FIGURE 15 ), 10–15 in number, although in the mature bracts these often had been lost. The nematocysts were located on a pronounced mesogloeal protuberance situated on the upper side of the bract a short distance from, but not at, the distal end of the bract. This mesogloeal protuberance was more marked in the younger bracts. The nematocysts were of the same type as for Resomia convoluta but larger, measuring 125µm in length and 28µm in diameter. The shaft of the discharged nematocyst measured 95µm.

Palpon: The palpons ( Fig. 16) were largely structureless bags, measuring up to 9 mm in length and 2.5 mm in maximum width; older ones were filled with an amorphous substance. However, there was a small but marked cluster of about 100 nematocysts at the distal end. These nematocysts were of the same type and dimension as those found on the bract. Although the palpons narrowed towards their bases, there was no distinct buttonlike structure as was found on those of Resomia convoluta . The palpacle, arising at the very base of the palpon, had the semblance of being annulated but there were no signs of any nematocysts along its length.

More than 140 palpons were found with the specimen, alongside 23 gastrozooids. Thus, as was the case for Resomia convoluta , there appears to be at least six palpons present in each cormidium.

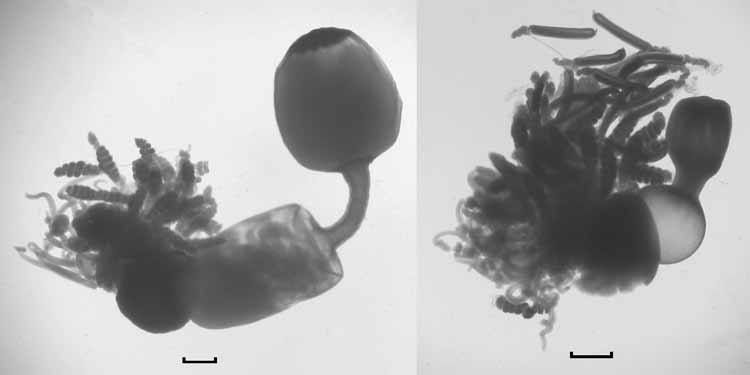

Gastrozooid and tentacle: The gastrozooids ( Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 ), which measured up to 11.6 mm in length and 2.8 mm in diameter, were extraordinarily variable in their shape, particularly with regard to the proboscis region. There was a distinctive basigastral region, which often occupied approximately one-third the length of the gastrozooid, and whose diameter was equal to or greater than its length. The stomach region took on a variety of shapes, varying from cylindrical to spherical. The proboscis region was usually demarcated from the stomach by a slight constriction, but in some cases ( Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 , left) this constriction resulted in a narrow tubular structure that separated the cylindrical stomach from the bulbous proboscis region. There were 12 longitudinal “liver stripes” arranged symmetrically around the proboscis, whose distal mouth region appeared to have been surrounded by darker pigmentation. Although the structure of this gastrozooid is very distinctive, nonetheless it is probably of no systematic value as the gastrozooids of siphonophore species are known to be extremely variable in shape, particularly with regard to the proboscis region.

The tentilla ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 ) on the tentacles of Resomia similis followed a similar pattern of development to those described for R. convoluta . They first appeared as simple tubular side branches on the tentacle ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 a) and quickly began to differentiate the terminal filament, then the cnidoband and pedicle. The cnidoband began to coil up into a loose spiral that gradually tightened ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 b–c) and then the involucrum began to develop ( Fig.18 View FIGURE 18 c). The involucrum continued to develop distally ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 d–f — the distal end of the involucrum is marked by a white line) until it entirely covered the cnidoband and the terminal filament ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 g). At this point the transformation of the cnidoband began and various stages of this are shown in Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 h–l. In Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 h the spiralled cnidoband was beginning to uncoil, while in Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 i–l the cnidoband consisted of straight segments that were in the process of being organised into the final arrangement. At two intermediary stages ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 i–j) this reorganisation necessitated that the cnidoband project distally beyond the involucrum, but at latter stages ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 k–l) it had largely been confined within the involucrum. Finally the involucrum ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 m–o) extended further so as to cover the entire cnidoband and formed a long distal tube with the retracted terminal filament occupying only the proximal half. The terminal filament arose from the distal end of the cnidoband, which did not recurve back proximally to form the beginnings of a fourth zag as was found to be the case in R. convoluta .

The types of nematocysts and their arrangements on the tentilla were exactly the same as in Resomia convoluta . The microbasic mastigophores (heteronemes), however, were much smaller, measuring 53– 66 x 16 µm, and less numerous, with only c. 100 being found on each side of the first 2½ spirals of the coiled cnidobands or about ¾ the length of the first zag on the other type. At the proximal end there were three rows on each side that, for the zigzagged form, continued up to about half the length of the first zag. The number of rows then rapidly decreased to one, and the individual nematocysts became more widely spaced. The anisorhizas (haplonemes) (53– 58 x 6.5–9.25µm) were present throughout the length of the cnidoband and, in the zigzagged form, it could be seen that there were only about four rows of these at the proximal end of the cnidoband. This number gradually increased to ca. 10 half-way along the first zag and, by the time the heteronemes had disappeared, there were about 20 rows. What were believed to be desmonemes ( 20–29 x 13.25–16µm) and small acrophores (13–18.5 x 5.23–8 µm) were found on the terminal filament. The doubled elastic band ran throughout the cnidoband for the spiralled type, and on the outer side of the first zag for the zigzagged type. It appeared to be much less welldeveloped than in R. convoluta .

Gonophores: Fragments of the stem bore both male and female gonophores. Both formed clusters borne on a single gonostyle ( Fig. 19 View FIGURE 19 ), with the female gonodendra forming much denser clusters than the male ones. The latter possessed gonophores at various stages of development. The largest mature male gonophore measured 1.7 x 1 mm (length/width), but all the female gonophores preserved were small, up to 0.45 mm in diameter, and immature. It was not possible to elucidate their cormidial arrangement.

| NIWA |

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Physonectae |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |