Eleutherodactylus wixarika, Reyes-Velasco, Jacobo, Ahumada-Carrillo, Ivan, Burkhardt, Timothy R. & Devitt, Thomas J., 2015

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3914.3.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C83CDA14-8528-4E15-B5A5-ECE88621196B |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5613539 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03915F52-5F52-A02A-FF23-469EFAACFBA6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Eleutherodactylus wixarika |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Eleutherodactylus wixarika View in CoL , new species

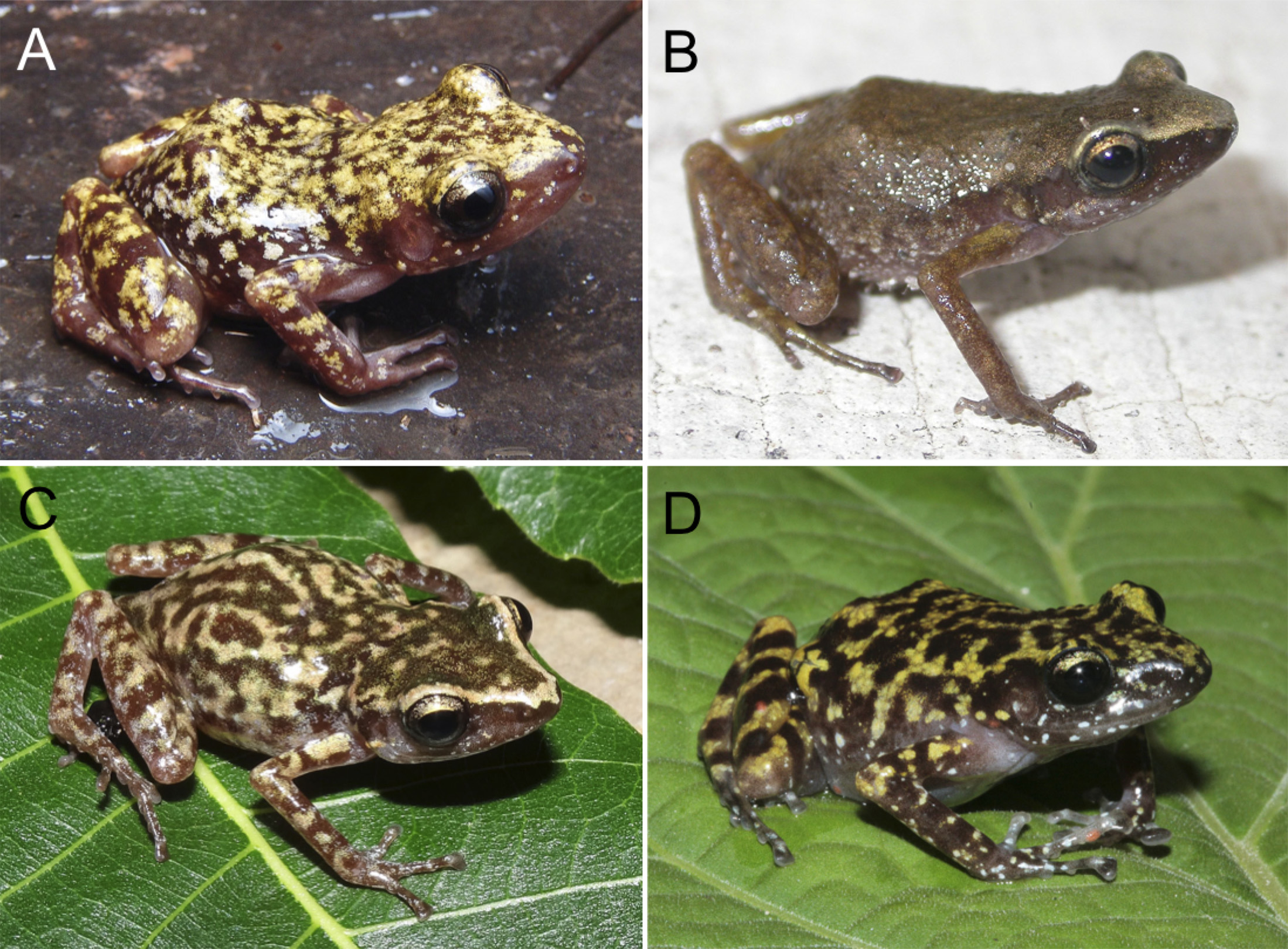

Holotype. MZFZ 27477. Adult male collected by Ivan Ahumada-Carrillo on July 6, 2011, at Bajío de los Amoles, Municipality of Mezquitic, Jalisco, Mexico (22.059429, -103.933983, 2,467 m; datum = WGS84; Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 , 5 View FIGURE 5 C–D).

Paratypes. MZFC 27478-27479, adult males, collected on the same day and place as the holotype by Ivan Ahumada-Carrillo ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ).

Diagnosis. Eleutherodactylus wixarika (Huichol pronunciation: /wiˈraɾika/) is a member of the E. longipes species series of the subgenus Syrrhophus as defined by Hedges et al. (2008). It is a medium sized frog compared to other members of the species series, with adult males measuring 21.2–24.5 mm in SVL; snout truncate and angular, not rounded from above (as defined by Savage, 2002 p. 171), but rounded in profile; head slightly wider than long, forming a flattened snout; tympanum visible, rounded, and small, with a diameter of tympanum/ diameter of eye ratio of 0.3–0.4; vocal slits absent in males; digital tips expanded conspicuously, but less than twice the width of narrowest part of digit on fingers three and four; digital discs slightly rounded to slightly truncate at tips ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B); body about as wide as head; dorsal coloration consisting of reddish orange or red ground color with white or pale gray on lateral portions and upper lip, totally covered in dark military green, brown to almost black blotches, which range from spots to reticulations; tuberculate dorsum; ventral coloration generally gray with some white spots and a bit of darker mottling; ventral skin areolate; no dark or pale interorbital bar present; no bars on thighs; iris orange.

This new species is distinguished from other members of the E. longipes species series by the following combination of characters: (1) absence of compact lumbar glands; (2) digital pads of third and fourth finger expanded, but less than twice width of narrowest part of finger; (3) medium size, adult males 21–25 mm; (4) tympanum visible; (5) red, reddish or rusty orange ground color covered by dark green, dark gray, or black reticulations and spots.

While Eleutherodactylus wixarika has not been collected in sympatry with any other species of the subgenus Syrrhophus , we believe that further collecting will find E. guttilatus , E. pallidus , E. teretistes and E. saxatilis either in near proximity or in sympatry with this species. Eleutherodactylus pallidus and E. teretistes are known from the lowlands and barrancas of Nayarit and west-central Jalisco, and there are faunal corridors entering deep into the southern portions of the Sierra Madre Occidental to the Sierra Huichola (e.g. Cox et al., 2012). Eleutherodactylus guttilatus is known from central Durango, and E. saxatilis occurs in southwestern Durango, and both may follow the eastern and western flanks respectively of the Sierra Madre to the Sierra Huichola. Eleutherodactylus wixarika may be distinguished from E. guttilatus by its smaller size, tuberculate dorsum, smaller and more concealed tympanum, and reddish ground color with dark green or gray reticulations ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 A). It can be distinguished from E. pallidus primarily by size and color pattern, as E. pallidus is a smaller frog, rarely over 20 mm; the color pattern of E. pallidus consists of plain brown ground color, as opposed to reddish in the new species; and E. pallidus lacks all traces of dark markings and reticulations on the dorsum. Also, in E. pallidus the tympanum is concealed, whereas in E. wixarika it is discernable ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 B). Eleutherodactylus saxatilis can be distinguished from E. wixarika by the following characteristics: larger body size, which is usually over 26 mm and up to 31 mm; outer digits more widely expanded, usually twice or more the width of the narrowest part of the finger on the third and fourth fingers; venter immaculate white as opposed to E. wixarika , which has a gray venter with both darker and lighter markings; presence of a distinguishable lumbar gland in E. saxatilis ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 D). Eleutherodactylus teretistes has smooth dorsal skin, while E. wixarika has a tuberculate dorsum; E. teretistes has a light brown or tan ground color vermiculated with dark brown, as opposed to E. wixarika which has a red or reddish orange ground color, and dark green or gray reticulations which may be broken up into spots. Furthermore, E. teretistes has a diagnostic light colored line, starting on the snout, following the outline of the head above the nostrils, above the eyes, onto the shoulders and then fading towards the back. This light line is present on all specimens of E. teretistes that were observed in the field, including individuals from Sinaloa, Nayarit and Jalisco. This line is not present on any of the three specimens of E. wixarika . This new species can be distinguished from E. modestus by its larger size (males 21–25 mm SVL, vs <20 mm in E. modestus ); also E. modestus has a uniform white or cream ventral coloration, whereas in E. wixarika it is darker gray with white spots and darker mottling.

Description of the holotype. Relatively small size (21.9 mm SVL); head slightly wider than long, 7.3 mm in length, 7.7 in width, about as wide as body; snout truncate, angular, non-rounded from a dorsal view but rounded from a lateral profile; tympanum distinct and rounded, no distinct supratympanic fold, greatest diameter of tympanum 1 mm; greatest diameter of eye 2.4 mm, tympanum-to-eye ratio 0.4; eyelid 1.9 mm wide, approximately three fifths of the IOD; first finger same length as second finger; finger lengths from shortest to longest 1-2-4-3, with 1 and 2 equal; digital pads on fingers three and four moderately expanded, approximately 1.8 times the narrowest point of the digit; three palmar tubercles; inner palmar tubercle about 70% as large as middle palmar tubercle, outer palmar tubercle about half as large as the middle palmar tubercle; toe lengths from shortest to longest 1-2-5-3-4. FL 8.5 mm, TL 10.1 mm, FeL 9.1 mm, FoL 6.6 mm, IND 2.2 mm, IOD 2.9 mm, END 2.3 mm. FeL to SVL 42%, TL to SVL 46%, FL to SVL 39%, HL to SVL 33%, HD to SVL 35%. Dorsal skin tuberculate; lateral skin and ventral skin areolate. Vocal slits absent in males. See Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 for a photograph of the holotype in life. Coloration in preservative is a light ground color of tan to orange, with dark gray almost black reticulations covering the entire dorsal surface of the head, back and arms. Thighs orange-yellow with some dark gray blotches. Ventral coloration is cream and gray with some darker and paler spots.

Variation. The three known specimens of this species vary little in morphology and color pattern. One specimen is larger than the type, measuring 24.5 mm. The dorsal ground color is always reddish with darker reticulations, the intensity and width of which varies from individual to individual, making one individual seem darker. Measurements for the holotype and paratypes are given in Table 1 View TABLE 1 .

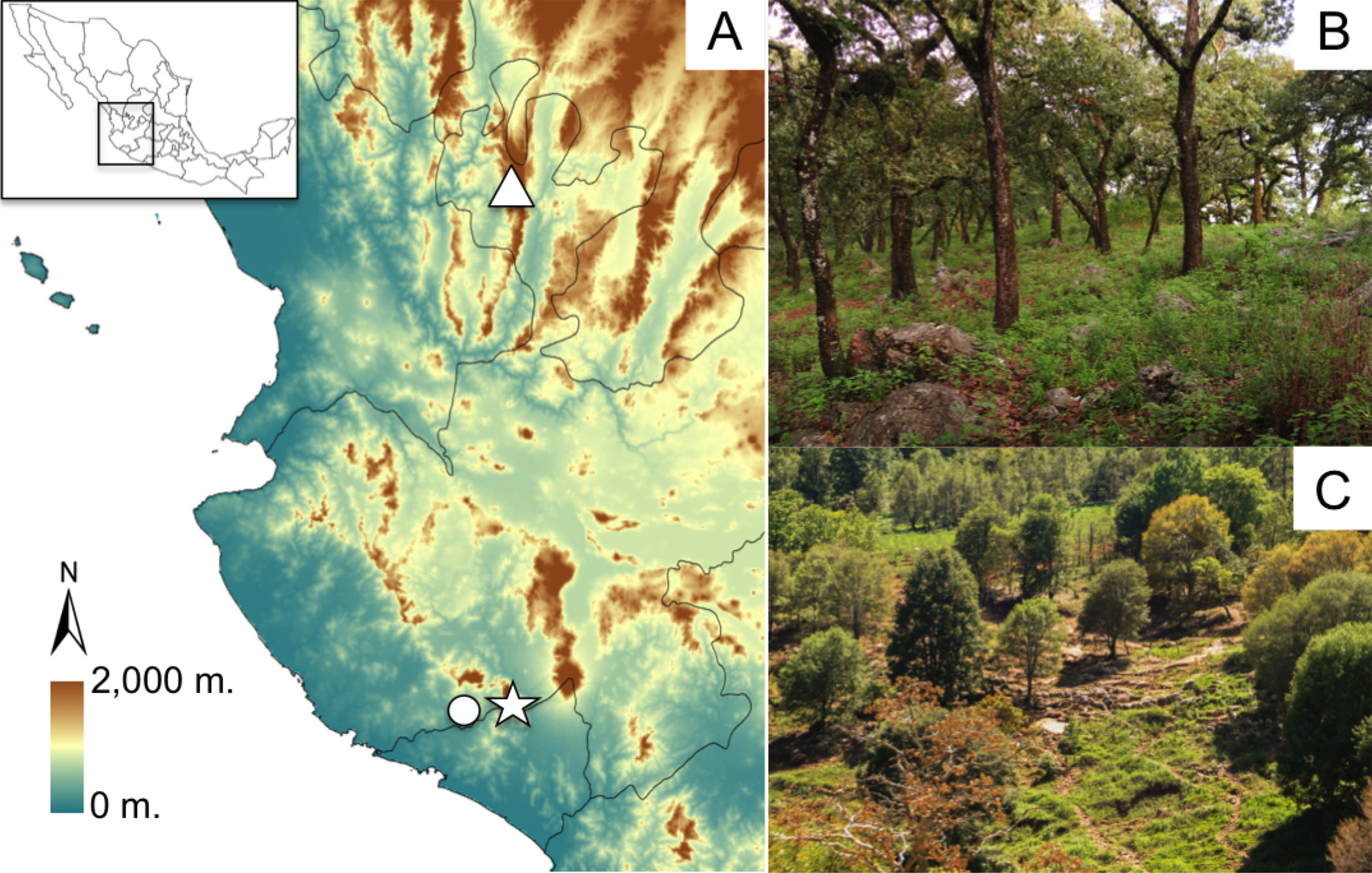

Distribution and ecology. This species has been collected in the Sierra Huichol in the municipality of Mezquitic, Jalisco ( Fig. 6A View FIGURE 6. A ). It likely occurs continuously at high elevations throughout this mountain range and possibly also in other nearby mountain ranges in Jalisco, Zacatecas, Nayarit and Durango. It has been collected between 2400–2500 m at the type locality in pine forest ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6. A C). All specimens were collected in July, which is the beginning of the rainy season in western Mexico and likely the breeding season for these frogs.

Etymology. Eleutherodactylus wixarika is a patronym honoring the Wixárika people, better known by their Spanish name, Huicholes. Once widespread in the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Zacatecas, Durango and San Luis Potosí, the Wixárika people still inhabit the area around the type-locality of this frog, and the Sierra Huichol mountain range remains one of the last outposts of their language and culture.

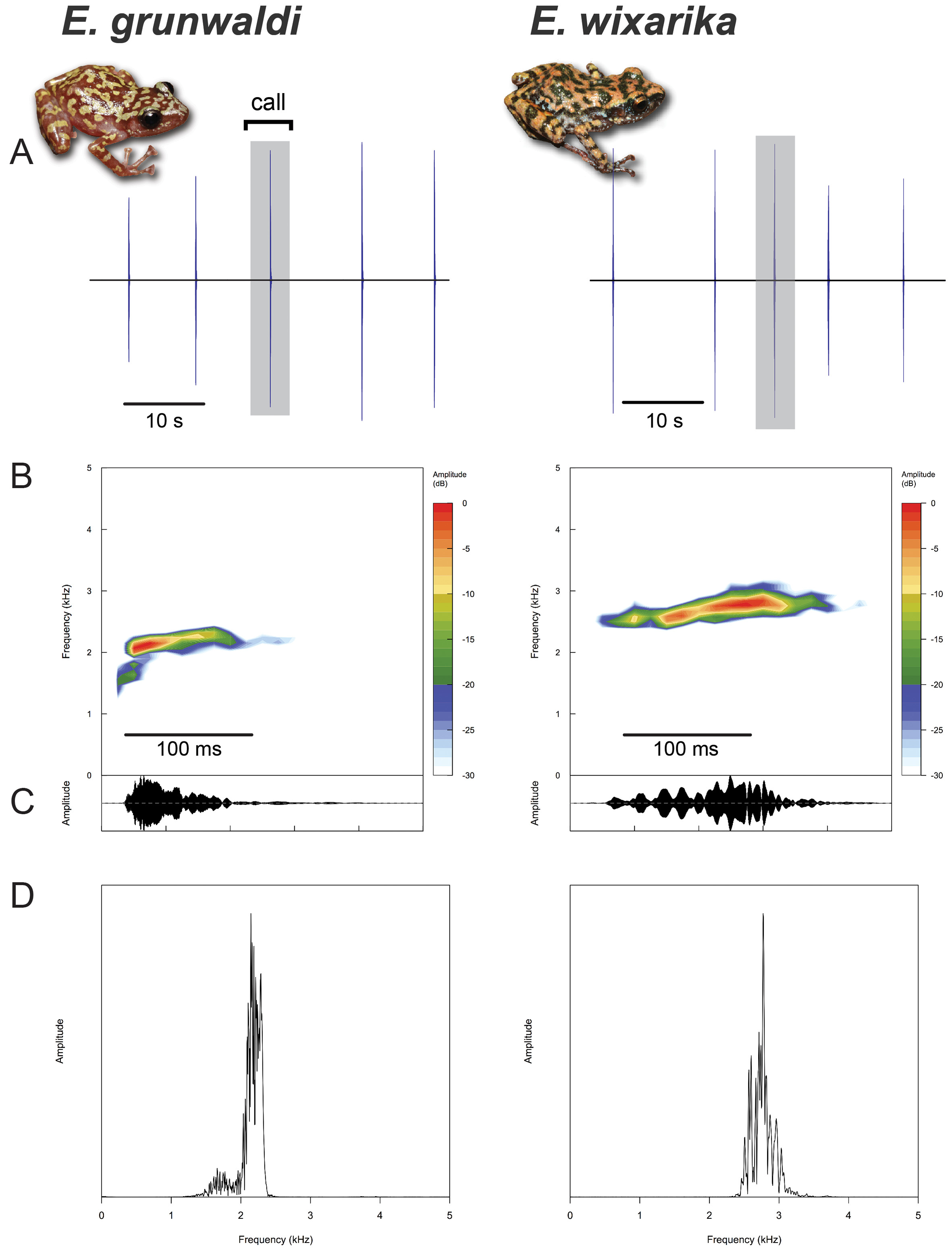

Advertisement calls. Like other members of the subgenus Syrrhophus , the advertisement call of these species consists of a short note best described as a “chirp” or “peep”. These notes are relatively narrow band (<500 Hz), nearly pure-tone bursts of acoustic energy organized into a discrete train repeated about 6 times per minute ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 , Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ). The fundamental frequency contains nearly the same amount of energy as the dominant frequency in both species (not shown). Compared to E. wixarika , the call of the larger species E. grunwaldi is much shorter (70 vs. 130 ms), ascends to its dominant frequency more rapidly, and has a lower dominant (and thus fundamental) frequency (2100 vs. 2700 Hz). The calls of both species show substructure within a call, but the pulses of acoustic energy are irregular in timing and duration. The signals of both species show very slight frequency modulation from beginning to end. Although Syrrhophus may produce an irregular introductory trill prior to a call bout ( Fouquette 1960), our recordings do not contain any trills.

Advertisement calls. Spectral and temporal acoustic properties of male advertisement calls differ between the two new species described here. Few descriptions (and even fewer recordings) of Syrrhophus advertisement calls have been published. Fouquette (1960) described the calls of Eleutherodactylus marnockii , E. pipilans , and E. nitidus . Dixon (1957) reported reciprocal calling by female E. angustidigitorum , a behavior that has been reported in at least two other eleutherodactylids ( Schlaepfer & Figeroa-Sandí, 1998; Stewart & Rand, 1991). It is not known whether female E. grunwaldi or E. wixarika call.

The small size of Syrrhophus imposes constraints for acoustic communication ( Gerhardt & Huber, 2002), namely the limited communication range of high-frequency calls. Like many other eleutherodactlyids, Syrrhophus increase their broadcast range by calling from elevated perches. Males of some species call from rock crevices ( Fouquette 1960), which may serve to amplify the signal by acting as a secondary resonator ( Penna & Solís, 1996).

Evolutionary relationships and biogeography. Twenty-four species of Syrrhophus occur in mainland Central and North America, all of them included in the Eleutherodactylus (Syrrhophus) longipes species series as defined by Hedges et al. (2008). This species series is further split into six species groups, which were first defined by Lynch (1970) and revised by Hedges (1989) and Hedges et al. (2008).

Eleutherodactylus grunwaldi View in CoL shares similarities with several members of the subgenus, including the species of the E. longipes View in CoL and E. marnockii View in CoL species groups as defined by Lynch (1970), as well as E. saxatilis View in CoL and E. interorbitalis View in CoL . Similarities include general coloration, size and the presence of greatly expanded digital discs ( Figs. 1–4 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 ). Lynch (1970) considered E. longipes View in CoL and E. dennisi View in CoL to be closely related and Farr et al. (2013) commented that they might be conspecific. Eleutherodactylus longipes View in CoL is restricted to karst formations in the Sierra Madre Oriental, from Coahuila to Hidalgo ( Lemos Espinal & Smith, 2007a, 2007b; Lynch, 1970), while E. dennisi View in CoL is known from several caves in southern Tamaulipas and eastern San Luis Potosí ( Lemos-Espinal & Dixon, 2013; Lynch, 1970). Both species resemble E. grunwaldi View in CoL in general color pattern, large size and by having broad digital discs. The marnockii View in CoL species group consists of E. marnockii View in CoL , E. guttilatus View in CoL and E. verrucipes View in CoL . Eleutherodactylus marnockii View in CoL is restricted to central Texas, eastern Chihuahua and northern Coahuila ( Lynch 1970), while E. guttilatus View in CoL it is restricted to the Chihuahuan Desert, the Mexican Plateau and the western versant of the Sierra Madre Oriental ( Lynch, 1970). Finally, E. verrucipes View in CoL is known from the Sierra Madre Oriental and associated ranges (Arenas- Monroy et al., 2012; Farr, et al., 2007). All three members of the E. marnockii View in CoL species group are similar to E. grunwaldi View in CoL in general dorsal coloration, body proportions and expanded digital discs, however they are smaller and their discs are not as broad as in E. grunwaldi View in CoL .

While general morphology would suggest a close relationship of E. grunwaldi View in CoL with the five species mentioned above, this seems unlikely from a biogeographical perspective. The entire range of the E. longipes View in CoL and E. marnockii View in CoL species groups falls east of the continental divide, in Atlantic or interior drainages, while E. grunwaldi View in CoL is known only from one mountain range on the Pacific Coast. The only species resembling E. grunwaldi View in CoL that inhabits the pacific versant of Mexico is E. saxatilis View in CoL . This species was formerly assigned to the genus Tomodactylus , which was later synonymized with Eleutherodactylus View in CoL by Myers (1962); all the former species of Tomodactylus are now included in the E. nitidus View in CoL species group of the subgenus Syrrhophus ( Hedges et al. 2008) . Eleutherodactylus saxatilis View in CoL is known only from the western flanks of the Sierra Madre Occidental in Durango and Sinaloa ( Webb, 1962). Like several of the species mentioned above, E. saxatilis View in CoL shares similarities in color pattern, digital pad shape and size to E. grunwaldi View in CoL . However, in E. saxatilis View in CoL the digital discs are not as broad and conspicuous lumbar glands are present.

Preliminary phylogenetic analysis of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene suggests that E. grunwaldi View in CoL is not closely related to the members of the E. longipes View in CoL and E. marnockii View in CoL species groups of northeastern Mexico discussed above (Devitt, unpublished). It is important to note that these species that share similarities in coloration and morphology to E. grunwaldi View in CoL also share a similar saxicolous existence, and thus these similarities are likely a result of adaptation to similar environments rather than recent, shared evolutionary history. Instead, E. grunwaldi View in CoL appears to be most closely related to members of the E. modestus View in CoL species group of Hedges et al. (2008) (Devitt, unpublished).

Eleutherodactylus wixarika View in CoL shares several morphological similarities with other members of the subgenus, including E. pallidus View in CoL , E. modestus View in CoL and E. teretistes View in CoL , which belong to the E. modestus View in CoL species group of Lynch (1970) and Hedges et al. (2008). Eleutherodactylus pallidus View in CoL is known from the Pacific lowlands, coastal sierras and inland barrancas of Nayarit and northwestern Jalisco ( Lynch, 1970, Ponce-Campos et al., 2003). This species is distinguishable from the E. wixarika View in CoL by its smaller size and dorsal coloration lacking any dark markings. Eleutherodactylus modestus View in CoL is known from the Pacific lowlands and nearby coastal mountain ranges of Jalisco and Colima ( Lynch 1970). This species shares the red ground coloration of E. wixarika View in CoL , however, E. wixarika View in CoL is larger and has a dark gray ventral coloration, as opposed to light cream or white in E. modestus View in CoL . Eleutherodactylus teretistes View in CoL is known to occur along the Pacific versant of the Sierra Madre Occidental in southeastern Sinaloa and Nayarit, as well as in coastal mountain ranges of southwestern Nayarit and northwestern Jalisco ( Lynch, 1970, Ahumada-Carrillo, et al., 2014). Eleutherodactylus teretistes View in CoL can be distinguished from E. wixarika View in CoL primarily based on skin texture and color pattern (see above). Eleutherodactylus pallidus View in CoL and E. teretistes View in CoL occur in Nayarit and Jalisco at lower elevations, with E. pallidus View in CoL known from 0–1225 m ( Lynch 1970) and E. teretistes View in CoL known from 300–1630 m ( Lynch, 1970, Ahumada-Carrillo, 2014). The deep barrancas that intersect the southern Sierra Madre Occidental serve as corridors to many lowland species ( Ahumada-Carrillo et al., 2014; Cox et al., 2012). In the case of E. wixarika View in CoL , the Río Atengo, a tributary of the Río Grande de Santiago, might have allowed an ancestor of these three species to reach the higher elevations of the Sierra Huichola. Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S ribosomal gene shows that Eleutherodactylus wixarika View in CoL is closely related to E. teretistes View in CoL (Devitt, unpublished). Based on the data discussed above, we believe that E. wixarika View in CoL might be closely related to E. pallidus View in CoL and E. teretistes View in CoL , and is probably a member of the E. modestus View in CoL species group.

Several of the most important topographic features of Mexico converge in central-western Mexico; these include the Sierra Madre Occidental, the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Pacific lowlands. The merging of these areas in the region has created a diverse assortment of unique habitats, and has made this region an important center of biodiversity, with many endemic species of vertebrates (e.g. Ceballos et al., 1995; Ceballos & Garcia, 1995; Peterson & Navarro, 2000). Many herpetological collections exist from the states of west central Mexico (Colima, Jalisco, Michoacán and Nayarit), but despite this, the herpetofauna of many areas in these states is still poorly known. We believe that future fieldwork in that area will result in new species discoveries, especially in isolated mountain ranges like the Sierra Cacoma and Sierra de Pihuamo in Jalisco, or the Sierra de Coalcomán in Michoacán.

Frogs of the subgenus Syrrhophus are among the most diverse groups of anurans in Mexico, but because of the lack of attention that they have received, many species are still awaiting formal description (personal observation). Additional fieldwork in western Mexico and elsewhere will certainly result in the identification of new species of this group, and a careful revision of museum material along with molecular analyses will help us to better understand the species-level diversity and evolutionary history of the group.

Conservation. Iron ore mining is an important economic activity in the mountains surrounding the Manantlán Biosphere Reserve, which is inhabited by E. grunwaldi View in CoL . Mining activities have had a negative impact in the ecosystems and communities around the area; for example, a new open pit mine has already destroyed one of the only localities for the rare Manantlán Long-tailed Rattlesnake ( Crotalus lannomi ) (Reyes-Velasco, personal observation; see also Reyes-Velasco et al. 2010 for a discussion on the biological importance of the region). The Sierra Huichol in northern Jalisco has some of the last remains of old growth forest in the Sierra Madre Occidental, which now contains less than 0.65% of its original extent (Lammertink, 1996). Logging and the conversion of forest into agricultural fields are some of the biggest threats to the biodiversity of the region. The Wixárika View in CoL or Huichol people, for whom E. wixarika View in CoL is named, have been greatly affected by new economic activities in the area, including new roads and mining projects, logging, agriculture and the expansion of drug cartels in recent years (authors personal observation; Boni, Garibay, & McCall, 2014; González-Elizondo et al., 2012; Liffman, 2011; Tetreault & López, 2011). The culture and traditions of the Wixárika View in CoL as well as the biodiversity of the area are increasingly threatened by human encroachment, and deserve protection if they are to persist in the long term.

| MZFC |

Museo de Zoologia Alfonso L. Herrera |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Eleutherodactylus wixarika

| Reyes-Velasco, Jacobo, Ahumada-Carrillo, Ivan, Burkhardt, Timothy R. & Devitt, Thomas J. 2015 |

Syrrhophus (

| Hedges et al. 2008 |