Paracoracias occidentalis

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00550.x |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9D4923C4-5CF1-4A01-B8A8-1EF3453247CA |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039187DA-FFED-FF98-6DF7-FAE3CCFBFBC6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Paracoracias occidentalis |

| status |

|

PARACORACIAS OCCIDENTALIS GEN. ET SP. NOV.

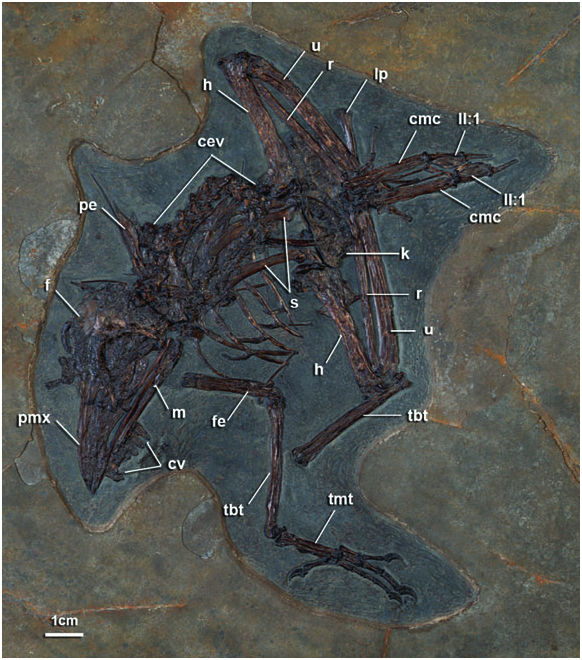

Holotype specimen: AMNH 30572 View Materials , a nearly complete skeleton lacking only the distal left hind limb (i.e. tarsometatarsus and pedal phalanges; Figs 2–7 View Figure 2 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 ; Table 1).

Etymology: ‘ Paracoracias ’ from the Greek affix ‘para’ for nearby or beside and to reflect phylogenetic placement in Coracii. ‘ occidentalis ’ reflects the New World or ‘Western’ provenience of the new species.

Locality: The holotype is from the Eocene Green River Formation. The Green River Formation represents an ancient and extensive lake system and has also yielded exquisite specimens of snails and insects as well as an exceptional record of vertebrates including birds, mammals, fish, and squamates ( Colbert, 1955; Grande, 1980; Bartels, 1993). Further proveniance information on this fossil is not available.

Diagnosis: The new species is differentiated from other Coracii below. Characters supporting placement in the Coracii are treated in the Discussion. Varying levels of completeness in material of other extinct Coracii and homoplasy across crown and stem Coracii prevented the optimization of unambiguous autapomorphies in the analysis. Species diagnosis is as for the taxon Paracoracias .

Paracoracias occidentalis differs from all parts of crown Coracioidea in the lack of an expanded descending process of the lacrimal (Character 11; Appendix 3). It is differentiated from both Coracioidea and Geranopterus alatus in the absence of an anterior projection on the postorbital process (Character 16; Appendix 3). It is further differentiated from these two taxa and Geranopterus milneedwardsi in the absence of an intermetacarpal process (Character 47; Appendix 3). The states for these characters in Paracoracias are presently optimized as plesiomorphies for Coracii.

Paracoracias occidentalis can be further differentiated from Coraciidae as the narial opening is not divided by an osseous bridge (Character 6; Appendix 3). Additionally, the posterior margin of the palatine is convex (concave in Coraciidae ; Character 18; Appendix 3), and the humeral bicipital crest is shorter in distal extent (Character 42; Appendix 3). Paracoracias occidentalis is differentiated from Brachypteraciidae , Geranopterus alatus , and G. milneedwardsi by subequal projection of metacarpals II and III (Character 50; Appendix 3), and it is further differentiated from Brachypteraciidae by a weakly projected anterior cnemial crest of the tibiotarsus (Character 61; Appendix 3). Geranopterus bohemicus is known only from a single tarsometatarsus; it was not used in differentiating Paracoracias : occidentalis from Geranopterus or Geranopteridae .

Paracoracias occidentalis is differentiated from Eocoracias brachyptera (the sole species in Eocoraciidae ) in possessing plesiomorphically broad nares. Eocoracias brachyptera is described as having a distinct slit-like narial opening (Mayr & Mourer- Chauviré, 2000; although see also comments in the description below). Paracoracias further differs from Eocoracias in proportions of the limb elements. Manual phalanx I:1 is shorter relative to total carpometacarpus length. The tarsometatarsus is also slightly longer relative to femoral and tibiotarsal proportions. The rostrum is proportionally broader than in Eocoracias and longer relative to hind limb elements (i.e. femur and tibiotarsus; see Table 1 and Mayr & Mourer-Chauviré, 2000). Finally, the ventral ramus (crus longus) of the ulnare is significantly longer than the dorsal ramus (crus breve; Character 45; Appendix 3) in Paracoracias but the rami of the ulnare are subequal in E. brachyptera ( Mayr & Mourer-Chauviré, 2000) . The condition seen in Paracoracias is also seen in Primobucco and Coraciidae View in CoL , but not Brachypteraciidae View in CoL .

Relative to all named Primobucco species , Paracoracias occidentalis differs in possessing a significantly broader beak, nares triangular with a flat ventral margin (ovoid in Primobucco ; Character 2; Appendix 3), more elongate processus postorbitalis (Character 15; Appendix 3); and significantly larger size (see Table 1). Support for the monophyly of Primobucconidae , or Primobucco , is not recovered in the phylogenetic analysis (see Discussion).

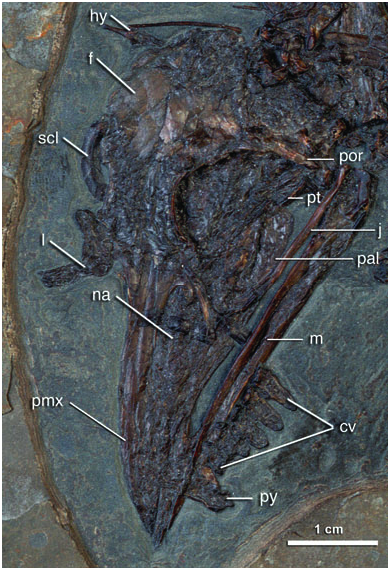

Description: The skull is broad and large relative to overall body size (e.g. significantly longer than either the humerus or tibiotarsus; Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). Beak length is just slightly greater than half of the skull length. The beak is curved in lateral view, with the peak curvature located anterior to the external nares. In this morphology the beak shape is more similar to Eurystomus than Coracias , Brachypteraciidae , Primobucco , or Eocoracias .

The external nares are large and broaden posteriorly. The long axis of the exposed left naris is approximately half the total length of the beak. The subtriangular shape of the naris approaches the condition developed in Coracioidea. The nares would be significantly broader dorsoventrally than in Eocoracias in which they are described as slit-like ( Mayr & Mourer-Chauviré, 2000). It is possible that this condition observed in Eocoracias may be a result of the plastic deformation common to birds from the Grube Messel (G. Mayr, pers. comm.). Currently known specimens may provide insufficient evidence to resolve this question with confidence.

An internarial septum is preserved as a sheet of bone visible through the left naris and inferred from the indistinct anterior edge of this opening ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). In the new species and in Coracioidea this septum grades smoothly into the anterior margin of the naris. In Coraciidae , an additional thin osseous sheet divides each naris, but this feature is absent in Paracoracias occidentalis . In Brachypteraciidae , a small osseous sheet rises from the posteroventral margin of the naris but does not contact the narial bar to divide the opening. The zone of the craniofacial hinge is slightly depressed but not strongly lineate. This condition appears also to be present in Eocoracias and was noted within crown Coracioidea ( Livezey & Zusi, 2006, 2007). The morphology of this region is highly variable, and is lineate in other traditional Coraciiformes recovered close to Coracii (e.g. some Alcedinidae and Momotidae ).

The postorbital processes are elongate; they closely approach the jugal bar and possibly contacted this element in life ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Such a morphology is seen in Eocoracias , Geranopterus , and Coracioidea (Mayr et al., 2004). The lacrimal head is expanded, a synapomorphy of Coracii known from all stem taxa except for Geranopterus for which it cannot be evaluated. Paracoracias also lacks an anterior projection of the postorbital process, a feature developed in all Coracioidea with the exception of polymorphism exhibited in Eurystomus orientalis (two of nine adult specimens of examined in this study lacked this process). The zygomatic process is elongate as in other Coracii.

The left palatine and posterior portion of the left pterygoid are exposed in the orbital region in oblique dorsolateral view ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Anteriorly the pterygoid is overlain by the palatine, and posteriorly it is in contact with the remains of the quadrate base. In the new species, some Brachypteraciidae ( Atelornis crossleyi and Brachypteracias leptosomus ), and Primobucco mcgrewi (Ksepka & Clarke, in press) this margin is slightly convex. By contrast, the posterior margin of the palatines is concave in ventral or dorsolateral view in Coraciidae and other Brachypteraciidae ( Atelornis pittoides and Uratelornis chimaera ). The frontal processes of the premaxillae are fused, although the suture between them remains visible posteriorly. The frontals are relatively broad, and rectangular in dorsal view ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). An interorbital septum is present. Remains of the right sclerotic ring are visible.

The mandible is partially exposed in oblique left dorsolateral view. The symphysis is relatively short, approximately one-fifth of total jaw length ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). A diminutive coronoid process is present. The broadly confluent lateral and posterior cotylae are partially exposed, whereas the medial portion of the articular is obscured by portions of the quadrate and jugal.

Portions of the hyoid apparatus are well preserved, but they appear to have been twisted such that the urohyal projects anteriorly ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). One ceratobranchial element is preserved in articulation with the fused urohyal and basihyal. Between the later elements the suture is incompletely obliterated. The paraglossale in the fossil appears to have been cartilaginous or absent. The urohyal is a welldeveloped elongate rod-like element similar to that in Brachypteracias leptosomus . In the specimens of Coracias garrulus and Coracias benghalensis examined, the urohyal was very poorly projected. This appears to be the result of a lack of complete ossification, as much of this element remains cartilaginous in the specimen of C. benghalensis depicted by Burton (1984: fig. 25). The basihyal is expanded at the contact with the ceratobrachials in both the new species and in extant Coracioidea, more so than in Meropidae and Todidae but less so than in Alcedinidae ( Burton, 1984) . There is a slight depression on the midline of the urohyal at its contact with the basihyal and a midline groove on the basihyal with two lateral depressions on the mediolaterally expanded area just distal to the inferred position of the ceratobrachial articulations. Several tracheal rings are preserved near the right side of the base of the sternal keel as well as between the right scapula and the right furcular ramus.

The presacral vertebral series is articulated and forms a tight U-shape from the back of the skull to terminate near the lower jaw where the sacrum is also located ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 4 View Figure 4 ). Eighteen presacral vertebrae are visible, although additional elements may have Skull

Maximum length 60.0 Rostrum, length (nasofrontal hinge to 30.6 premaxilla tip)

Orbit, diameter at midpoint 13.2 External nares, maximum length 12.6 Mandible, maximum length 50.0 Mandibular symphysis, maximum length 13.6

Vertebral column

Sacrum, length (estimated) 26.6 Pygostyle, midpoint anteroposterior diameter 4.3 Pygostyle, maximum height 9.6 been present. There is an osseous extension from the transverse processes to the postzygopophyses perforated by a small foramen in the third cervical vertebra ( Mayr & Clarke, 2003: character 52), a feature present in all taxa evaluated for the phylogenetic analysis except Trogonidae . The posterior thoracic vertebrae contain ovoid lateral excavations. The sacrum is exposed in ventral view but is largely obscured by overlying anterior cervical vertebrae and posterior skull fragments ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). At least one costal strut is present, which is developed in the part of the series correspondent with the area of the acetabulum. Four ribs bear fused, recurved uncinate processes.

Five free caudal vertebrae and the pygostyle are preserved in articulation. This portion of the caudal series is displaced and lies near the mandibular symphysis ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Two caudal vertebrae are preserved separately and are partially overlain by the anterior end of the sacrum. Additional free caudal vertebrae may have been present as well. Pygostyle morphology is nearly identical to Coracioidea in that the anterior margin is convex in lateral view with a conspicuous notch, the posterior margin is straight to slightly concave, and a projected discus is developed.

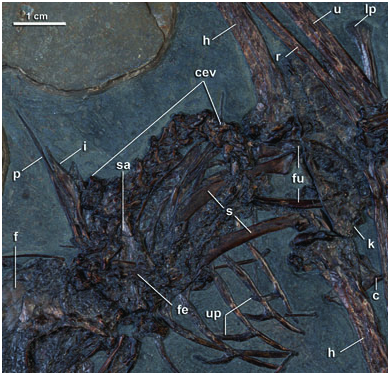

The right coracoid is preserved in ventral view but is mostly obscured by the proximal end of the right humerus and parts of the sternum and furcula ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ). A well-projected, pointed lateral process is

Pectoral girdle

Sternum, length on midline, anterior base of 35.5 carina to terminus

Scapula, maximum length (left, estimated) 36.0

Coracoid, maximum height (right, estimated) 26.2

Furcula, distance from apophysis to omal 21.5 tips on midline

Furcula, diameter at omal tip (left) 3.3

Pectoral limb

Humerus, maximum length (left/right) 43.7/43.6 Humerus, deltapectoral crest length 12.0 (right side)

Ulna, maximum length (right, estimated) 52.7 Radius, maximum length (right) 49.0 Carpometacarpus, maximum length (left) 25.9 Phalanx I.1 length (left/right) 7.4/7.5 Phalanx II.1 length (left/right) 10.6/10.9 Phalanx II.2 length (left/right) 8.4/8.4 Phalanx III.1 length (left/right) 5.3/5.3

Pelvic girdle

Ischium, maximum length from margin of 20.3 obdurator foramen (left)

Pubis, maximum length from margin of 30.1/29.3 obdurator foramen (left/right)

Pelvic limb

Femur, maximum length (left/right) 29.5/29.3 Tibiotarsus, maximum length (left/right) 39.8/39.6 Tarsometatarsus, maximum length (right) 19.2 Metatarsal I, maximum length (right) 5.4 Phalanx I.1 length (right, estimated) 8.1 Phalanx I.2 length (right) 5.8 Phalanx II.1 length (right) 7.0 Phalanx II.2 length (right) 6.4 Phalanx II.3 length (right) 5.3 Phalanx III.1 length (right) 6.6 Phalanx III.2 length (right) 5.3 Phalanx III.3 length (right) 7.4 Phalanx III.4 length (right) 5.9 Phalanx IV.1 length (right) 4.6 Phalanx IV.2 length (right) 4.0 Phalanx IV.3 length (right) 3.7 Phalanx IV.4 length (right) 5.6 Phalanx IV.5 length (right) 5.2 present. The medial coracoid margin flares slightly omally from its sternal contact and is distinctly notched at approximately the same level as the tip of the lateral process. The right scapula is visible in dorsal view, whereas the left is exposed in ventral view ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The scapula is shorter than the humerus and close in aspect to those of Coracioidea. The blade is recurved and expands slightly before tapering towards the distal end. The scapular glenoid facet is subcircular and projected from the shaft. The acromion may have been bifid. However, its medial surface is embedded in matrix so this feature cannot be verified.

The furcular apophysis is covered by the sternum, although its outline remains discernable ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The exposed omal tips are compressed mediolaterally. The sternum is exposed in right ventrolateral view. A spina externa is present. The apex of the sternal keel is projected anterior to the coracoidal sulci and extends to the posterior margin of the sternum. Lateral and medial posterior trabeculae are developed, with the lateral flared distally ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ).

The humeri are exposed in posterior view. The humerus is conspicuously shorter than the ulna ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The head is narrow and oblate with a welldefined distal margin in posterior view. This condition is developed in ground rollers but not in Coraciidae or in Geranopterus (Mayr & Mourer- Chauviré, 2000: fig. 8J). In Brachypteraciidae , the secondary tricipital fossa is relatively broad dorsoventrally excavating the humeral head and contributing to this well-defined margin. The deltopectoral crest is short, extending less than one-third of the total shaft length, and its dorsal margin is rounded ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The pit-shaped fossa for m. supracoracoideous insertion on the dorsal tubercle is conspicuous and deep. This fossa appears to be anteriorly directed, however, this orientation may be exaggerated by slight compression. The capital incisure is open and broad. The bicipital crest is relatively short, and its distal margin angles sharply into the shaft, more closely resembling the condition in Brachypteraciidae than Coraciidae . The shaft exhibits very little curvature. Distally, the m. scapulotriceps groove and a projected dorsal supracondylar process are visible ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ).

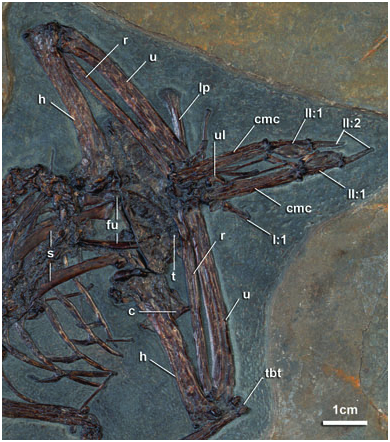

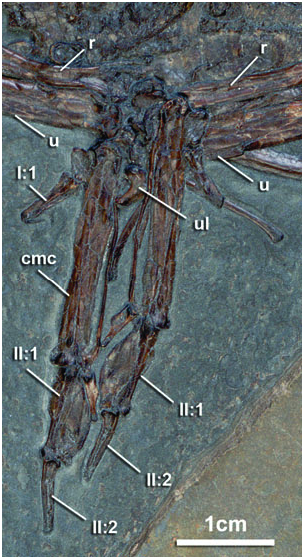

The radii, ulnae, and carpometacarpi are preserved in dorsal view ( Figs 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ). A tuberculated muscular attachment is present on the ulna between the olecranon process and the dorsal cotyla. The radius is robust, approaching nearly one half of the diameter of the ulna. The ulnare and radiale are in partial articulation with the carpometacarpus on both sides. The dorsal ramus (crus brevis) of the ulnare is markedly shorter than the ventral (crus longus; Figs 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ). In E. brachyptera , these rami are subequal in length.

The hand is shorter relative to the proximal wing elements when compared to Coraciidae or Brachypteraciidae but is comparable to E. brachyptera ( Mayr & Mourer-Chauviré, 2000; Table 1). The extensor process is low and weakly projected in dorsal view ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). Although it is with certainty less projected than Coraciidae , its relative lack of projection appears slightly exaggerated by the orientation of metacarpal I. The intermetacarpal space is narrow, with metacarpal III extremely thin and subparallel to metacarpal II ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). Metacarpal III just surpasses metacarpal II in distal extent as in Coraciidae , Eocoracias , and Primobucco . By contrast, metacarpal III significantly surpasses metacarpal II in distal extant in Geranopterus , Brachypteraciidae , and most groups of ‘higher landbirds’ (i.e. Meropidae , Momotidae , Todidae , Alcedinidae , Upupidae , Piciformes , Passeriformes ). The intermetacarpal process is developed as a small tubercle rather than the large triangular process present in Coracioidea. On the dorsal surface of metacarpal II, the extensor groove is well developed, and a large tubercle is associated with the retinaculum attachment. A small spike-like chip of bone distal to left phalanx I:1 may be homologous to the small alular claw documented for Primobucco perneri (Mayr et al., 2004; Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). However, no such element is visible associated with the right digit I, and this claw is absent in extant Coraciidae ( Stephan, 1992) . Phalanx II:1 bears a small internal index process comparable in development to that in Coraciidae and Eocoracias brachyptera but more projected than in Primobucco and Brachypteraciidae . Phalanx III:1 has a well-developed flexor tubercle.

The synsacrum is covered by the posterior skull elements, proximal cervical vertebrae, and left femur ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 3 View Figure 3 ). Only its left postacetabular portion is well exposed. The ischium tapers to a pointed terminal ischial process that conspicuously surpasses the dorsolateral iliac spine. The pubis is straight, extremely narrow, and tapering toward its distal extreme; it is not appreciably medially deflected ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). No pectineal process is developed, and the obturator foramen is small.

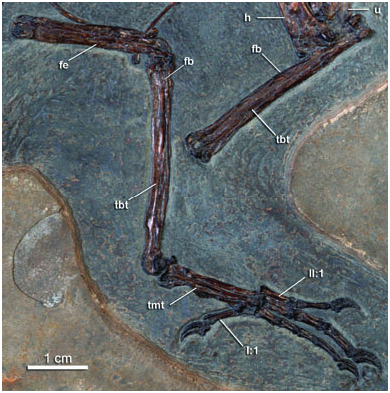

The right leg is articulated and exposed primarily in lateral view ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ). The disarticulated left limb is represented by the poorly exposed femur covered by the cervical series, and a tibiotarsus exposed in dorsal view near the wing elements ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ). The femur is straight. A free, ovoid ossification lies near the proximal end of the patellar groove. A small intratendinous ossification was also observed in articulated specimens of Coraciidae , Meropidae , and Alcedinidae . It is likely to be widely distributed, although easily lost in the maceration of skeletons. The cnemial crests are weakly projected as in Coraciidae , whereas in Brachypteraciidae they are significantly anteriorly projected. The distal condyles have approximately the same mediolateral extent. The fibula is elongate, extending just over two-thirds of the length of the tibia.

The right tarsometatarsus is abbreviated as in Coracii other than Brachypteraciidae ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ). It is preserved in oblique anterolateral view with digit I artefactually appressed to its lateral side. The tubercle for m. tibialis cranialis is very large and positioned towards the medial margin of the tarsometatarsus, a condition also seen in Primobucco . By contrast, this tubercle is less prominent and located closer to the midline of the tarsometatarsus in Coracioidea. The shape of the well-projected lateral hypotarsal crest and development of the lateral parahypotarsal fossa closely match the corresponding morphologies in Coracioidea. The trochlea of metatarsal IV closely approaches that of metatarsal III in distal extent. The trochlea of metatarsal II is not exposed. However, based on the position of the articulated proximal phalanges of this digit, it is likely to have obtained approximately the same distal extent as III. A dorsal sulcus at the fused contact between metatarsals III and IV extends the length of the element. The distal vascular foramen is not discernable.

Pedal digits III and IV are longer than the tarsometatarsus, and phalanx III:3 is longer than the proximal phalanges of this digit ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 , Table 1). The foot is anisodactyl and the third digit is longest.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Genus |

Paracoracias occidentalis

| Clarke, Julia A., Ksepka, Daniel T., Smith, N. Adam & Norell, Mark A. 2009 |

Eocoraciidae

| Mayr & Mourer-Chauviré 2000 |

Eocoracias

| Mayr & Mourer-Chauvire 2000 |

Eocoracias

| Mayr & Mourer-Chauvire 2000 |

Primobucconidae

| Feduccia & Martin 1976 |

Primobucco

| Brodkorb 1970 |

Primobucco

| Brodkorb 1970 |

Primobucco

| Brodkorb 1970 |

Brachypteraciidae

| Bonaparte 1854 |