Montina Amyot & Serville, 1843

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.37520/aemnp.2022.019 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10552717 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039387AD-136C-FFA6-FC78-B53246C5DE67 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Montina Amyot & Serville, 1843 |

| status |

|

Montina Amyot & Serville, 1843 View in CoL View at ENA

Montina Amyot & Serville, 1843: 363 View in CoL (description). Type species: Reduvius sinuosus Lepeletier & Serville, 1825 , by monotypy.

Montina: STÂL (1859) View in CoL : 197 (new species); STÂL (1865): 48 (key); STÂL (1872): 73 (list of species); WALKER (1873): 91 (list of species); LETHIERRY & SEVERIN (1896): 195 (catalog); CHAMPION (1899): 286 (list, diagnosis); PUTSHKOV & PUTSHKOV (1988): 115 (catalog); MALDONADO (1990): 234 (catalog); ZHANG & WEIRAUCH (2014): 341 (phylogenetic placement); ZHANG et al. (2016): 540 (phylogenetic placement); GIL- SANTANA (2019): 516 (new records).

Ploeogaster View in CoL (nec Amyot & Serville, 1843): STÂL (1859): 197 (new species); STÂL (1872): 73 (synonym).

Aristippus Stål, 1865: 48 (description in key). Type species: Aristippus fenestratus Stål, 1867 , by subsequent designation.

Aristippus: STÂL (1867) : 48 (description, no species assigned); STÂL (1867): 299 (new species); STÂL (1868): 99 (key); STÂL (1872): 74 (list, synonym of Montina View in CoL as subgenus); WALKER (1873): 93 (list of species, as synonym of Ploeogaster View in CoL ); LETHIERRY & SEVERIN (1896): 195 (catalog, as subgenus); PUTSHKOV et al. (1987): 103 (as valid subgenus); PUTSHKOV & PUTSHKOV (1988): 115 (catalog, as valid subgenus); MALDONADO (1990): 234 (catalog).

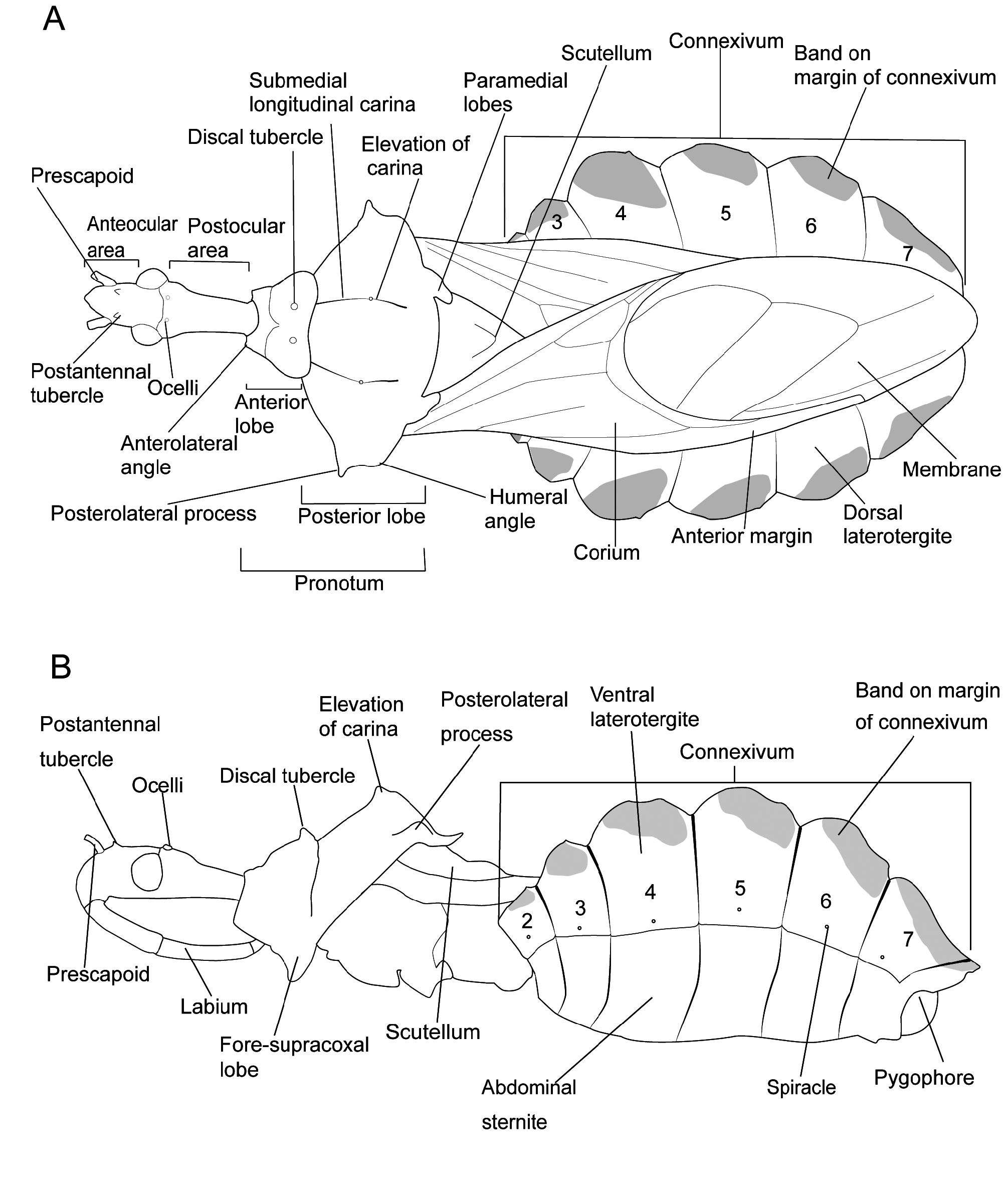

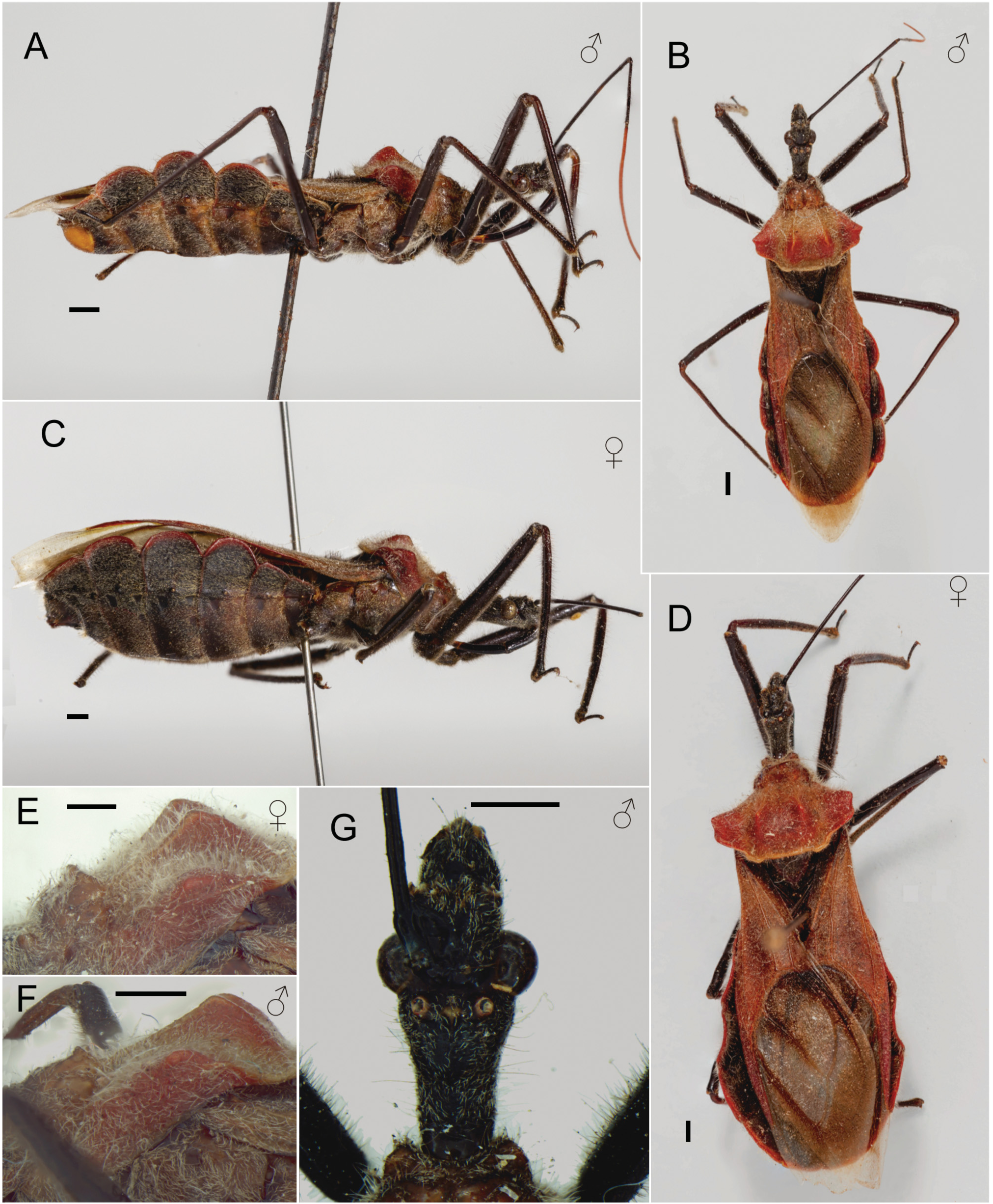

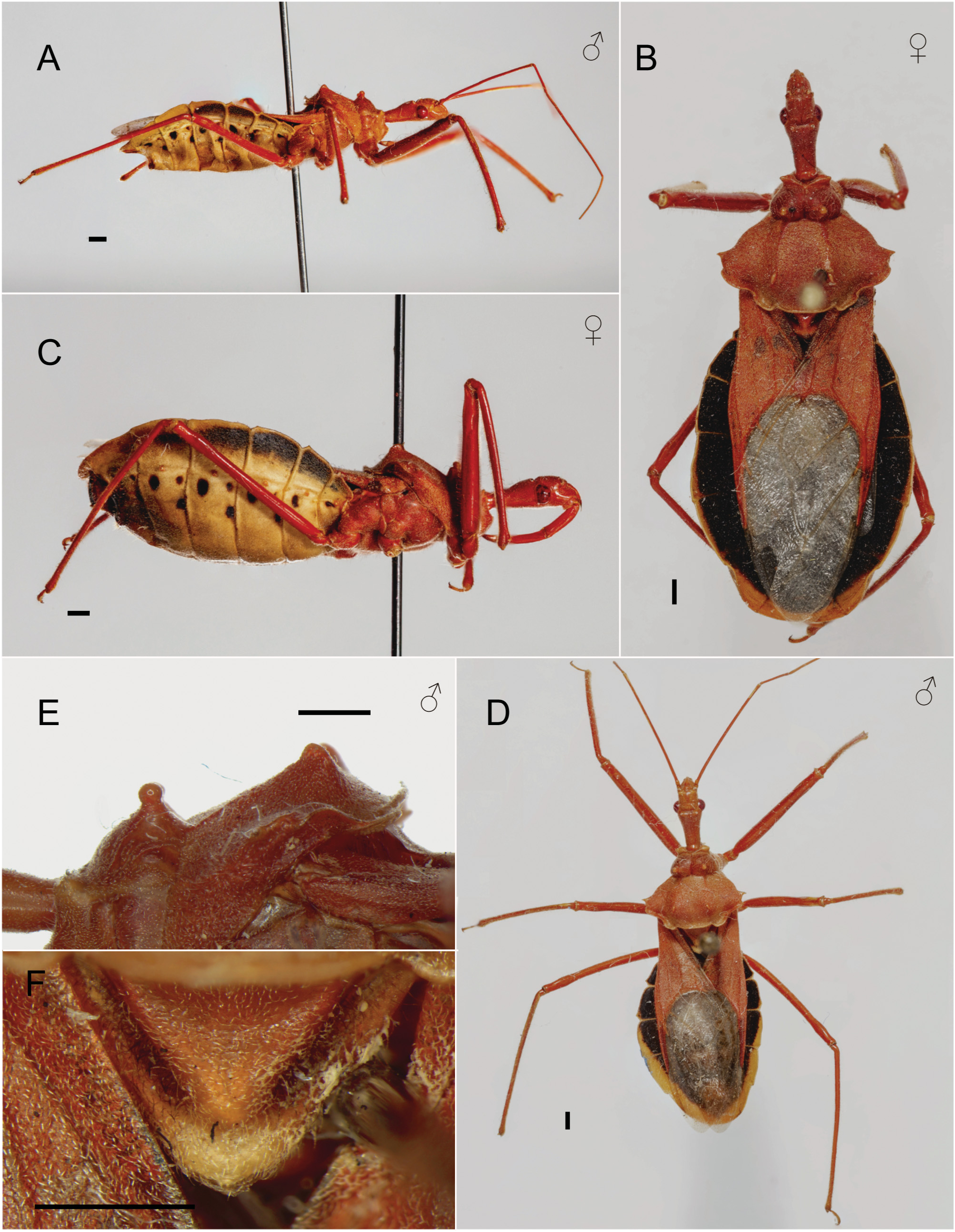

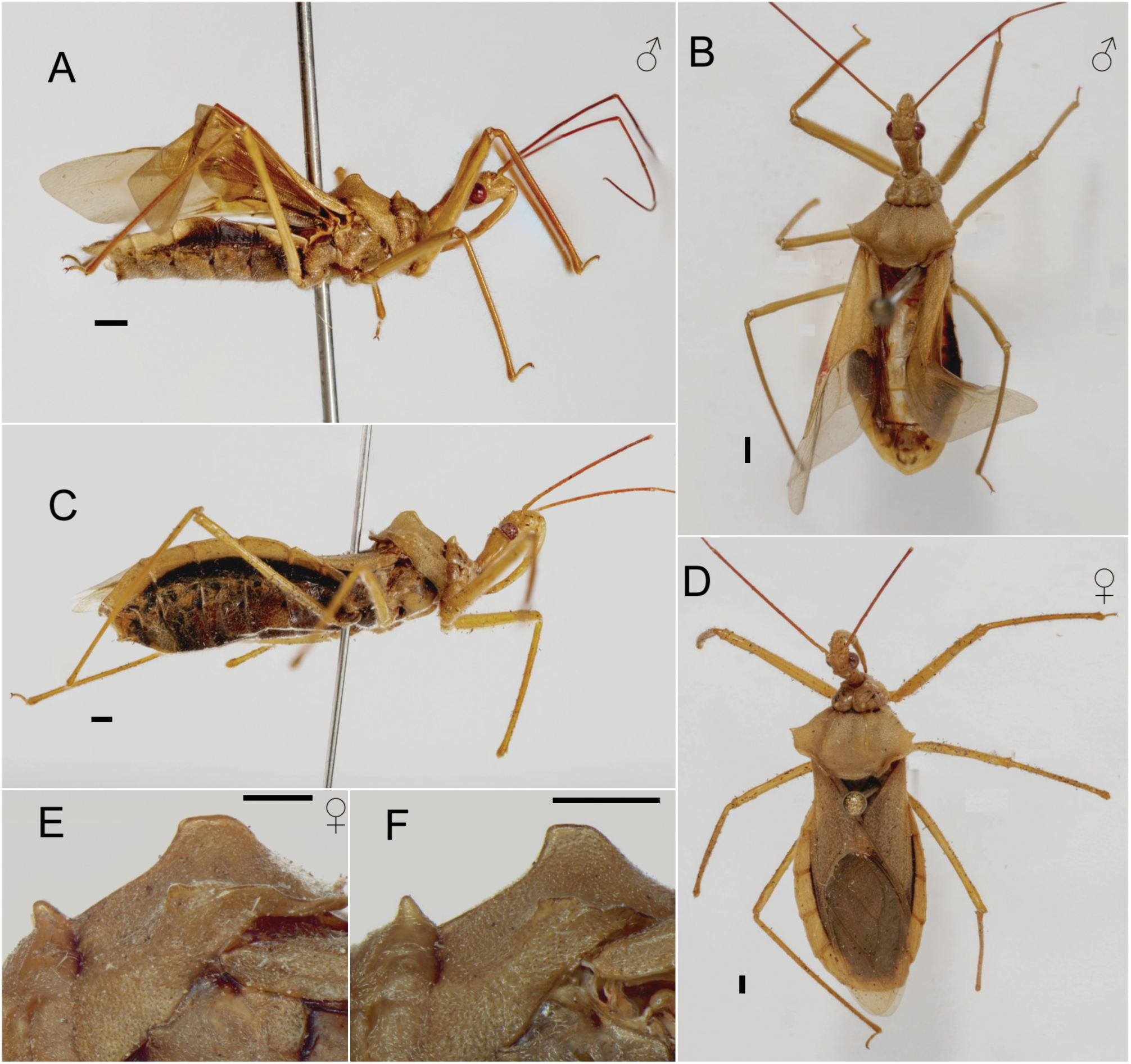

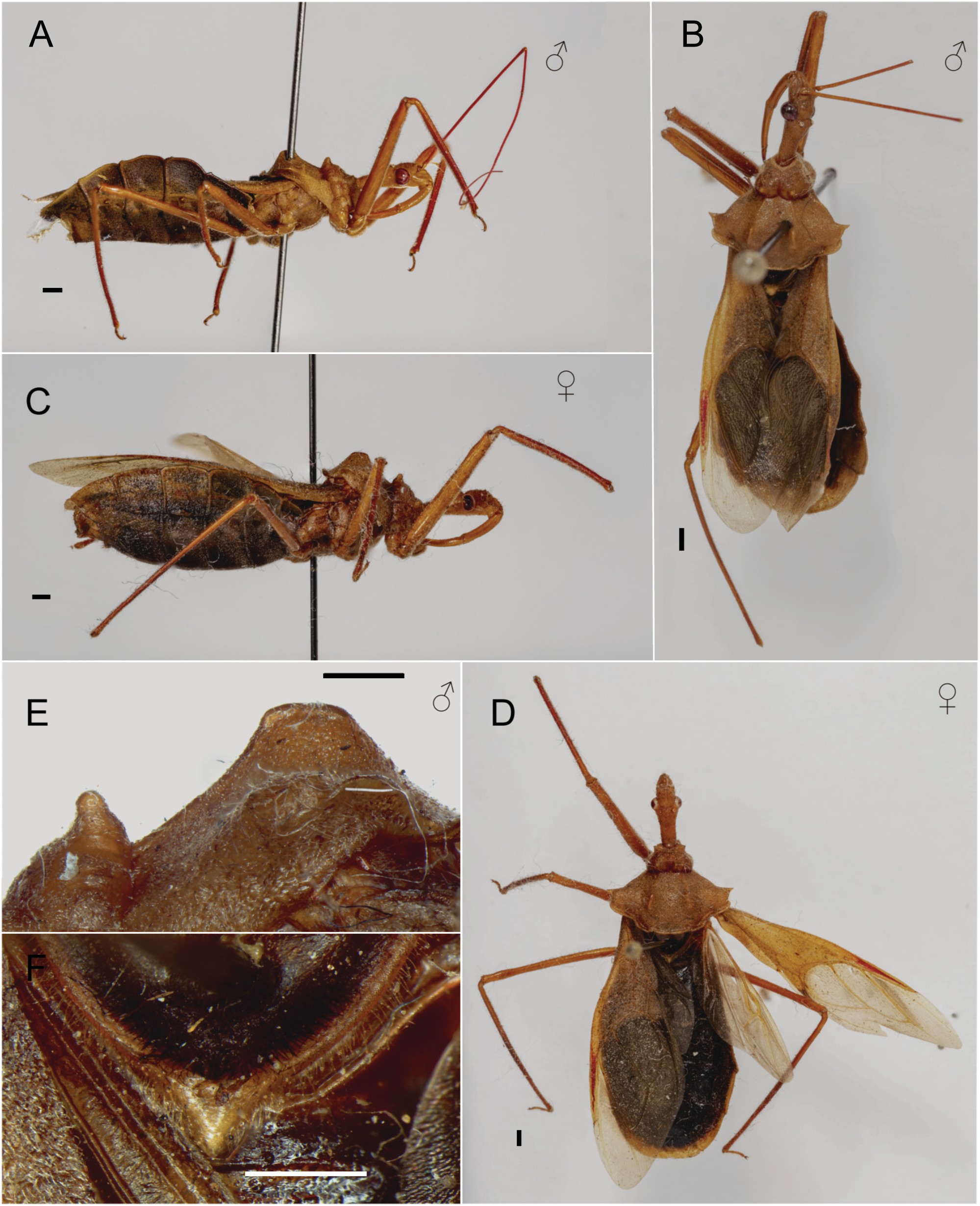

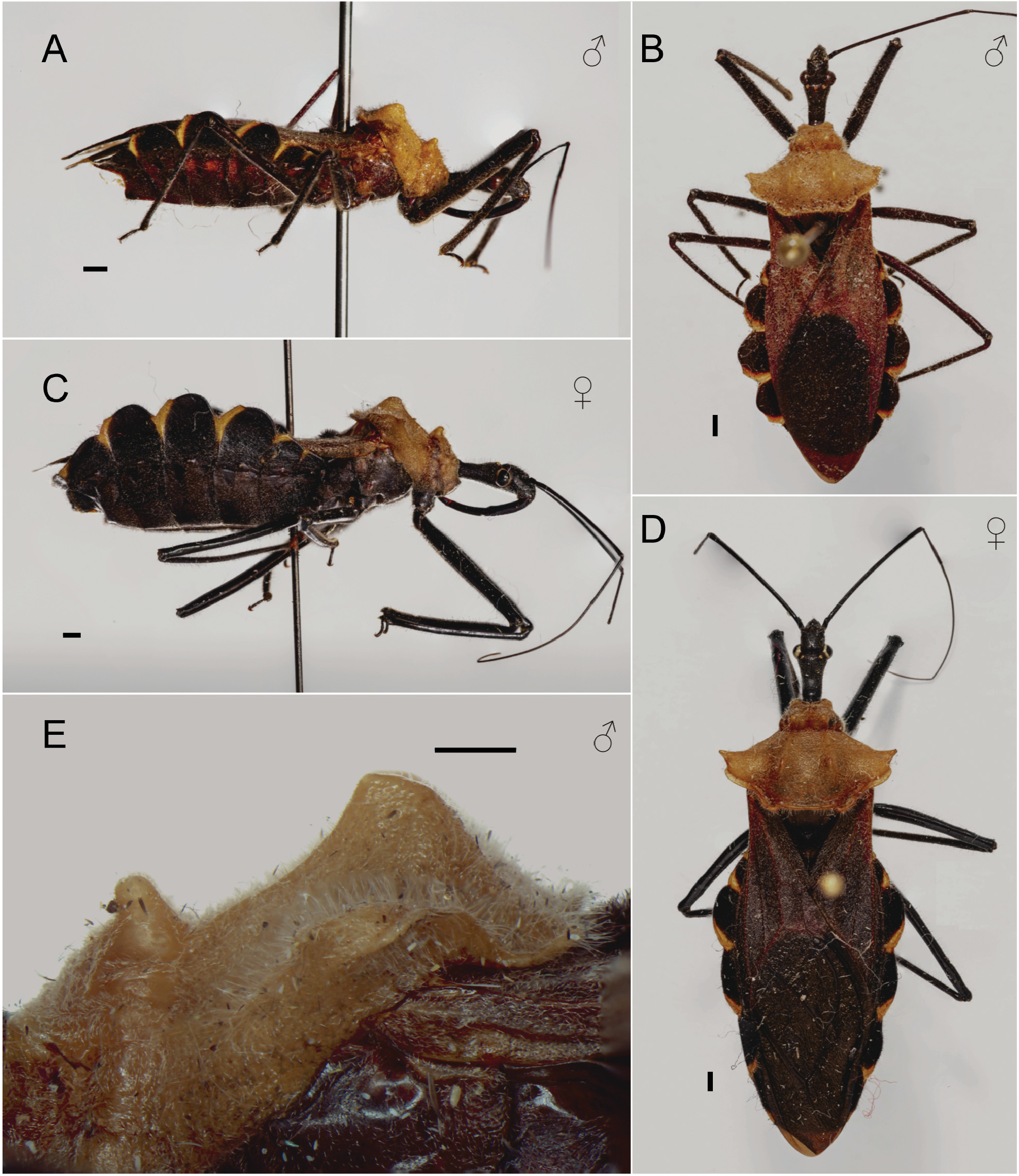

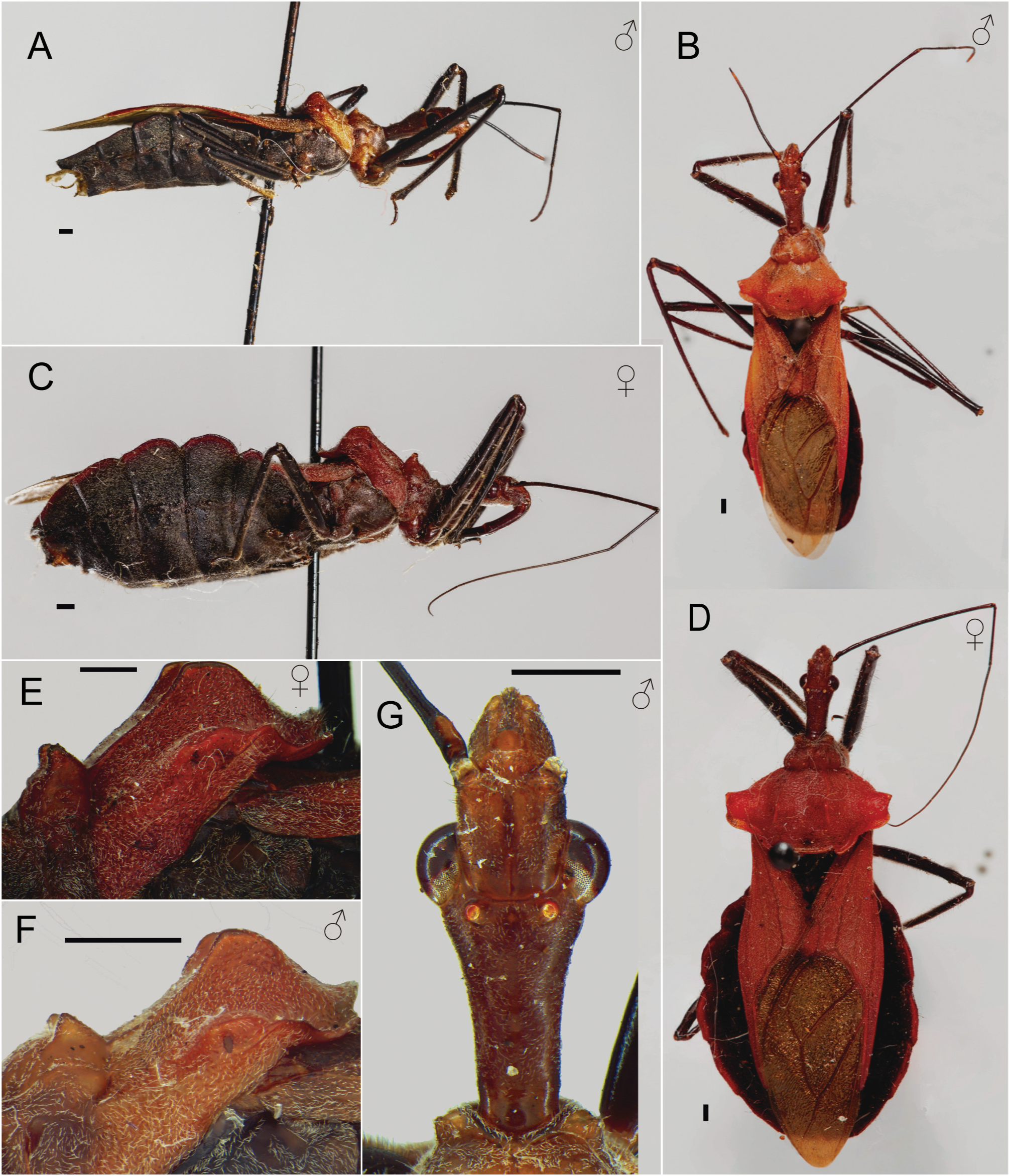

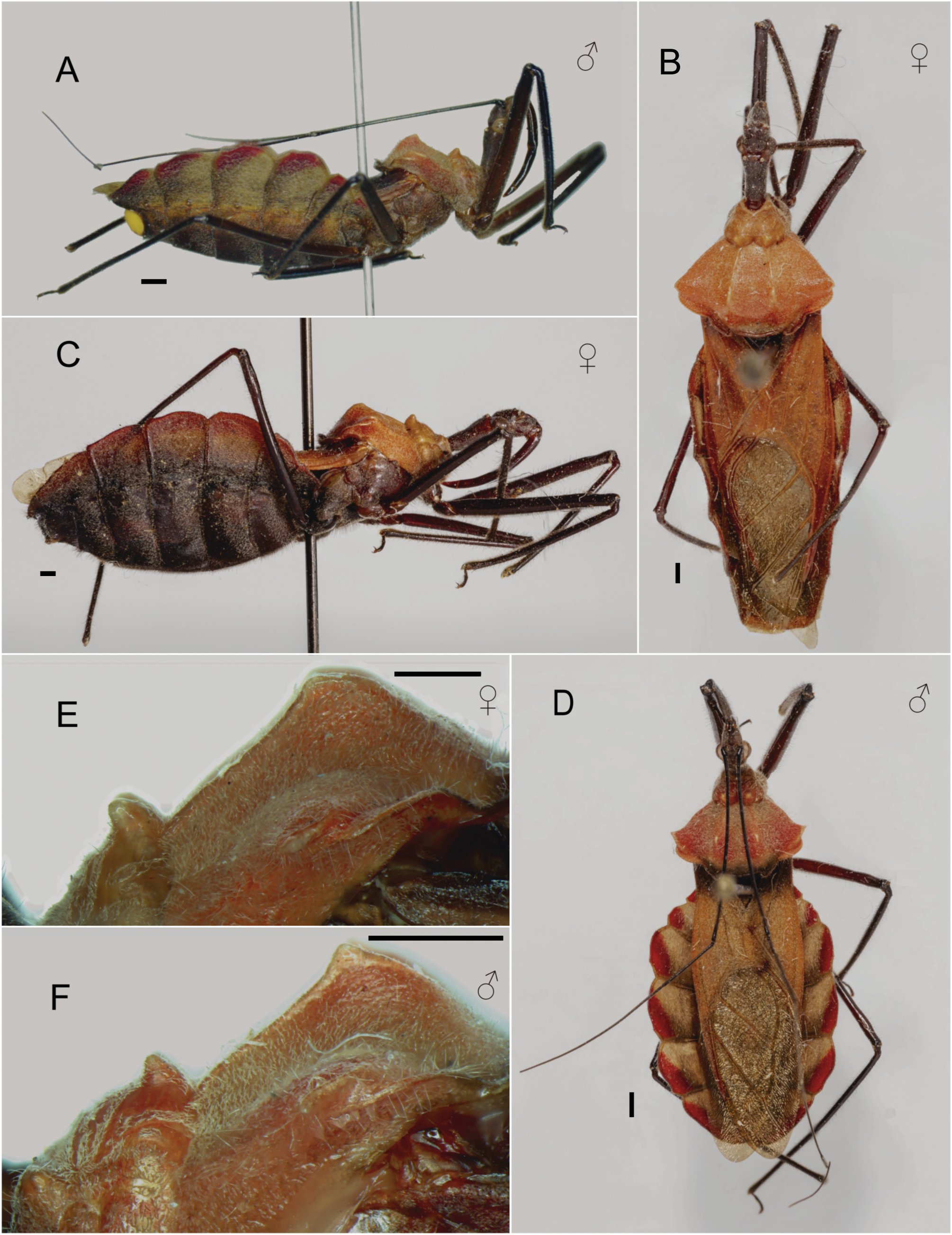

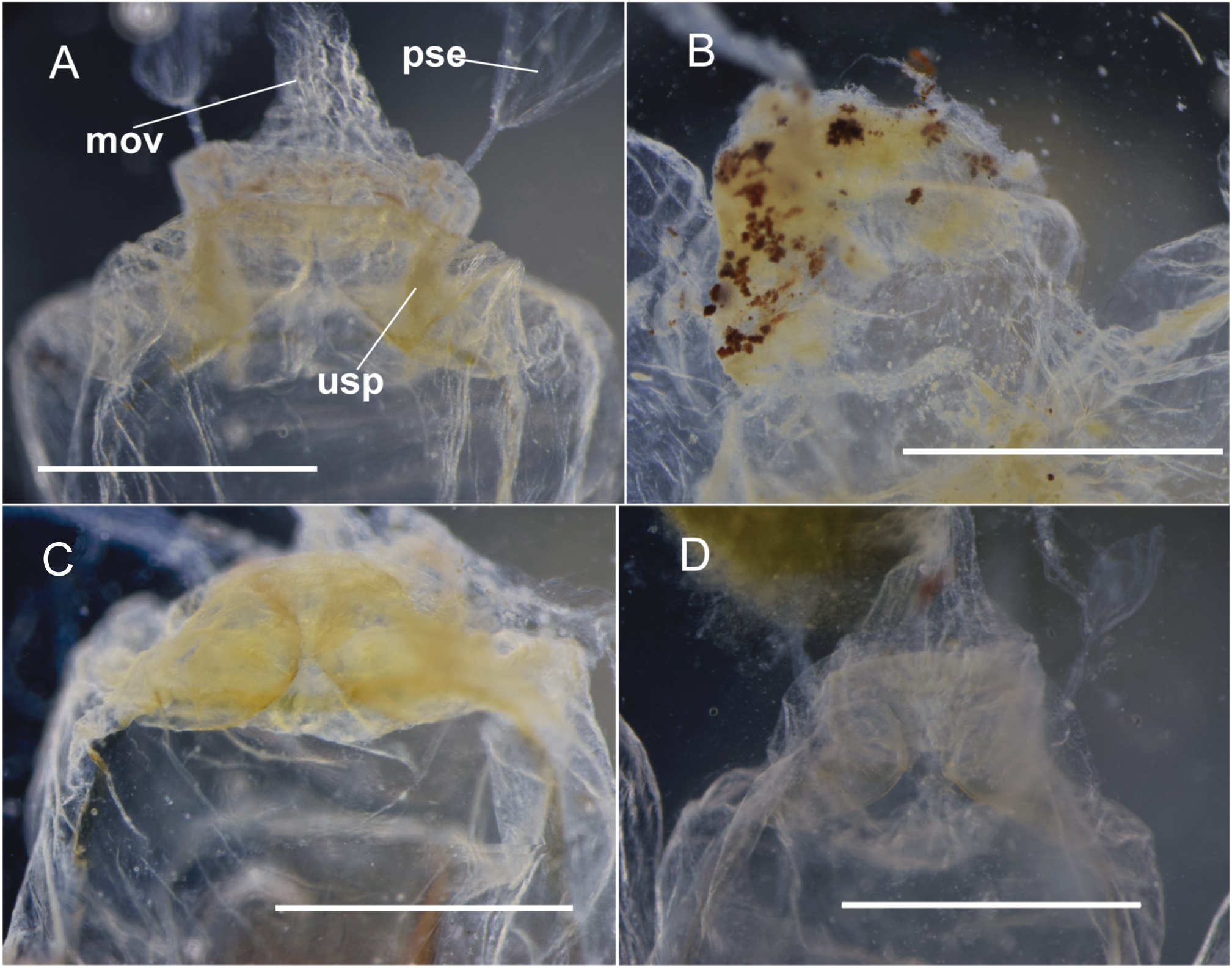

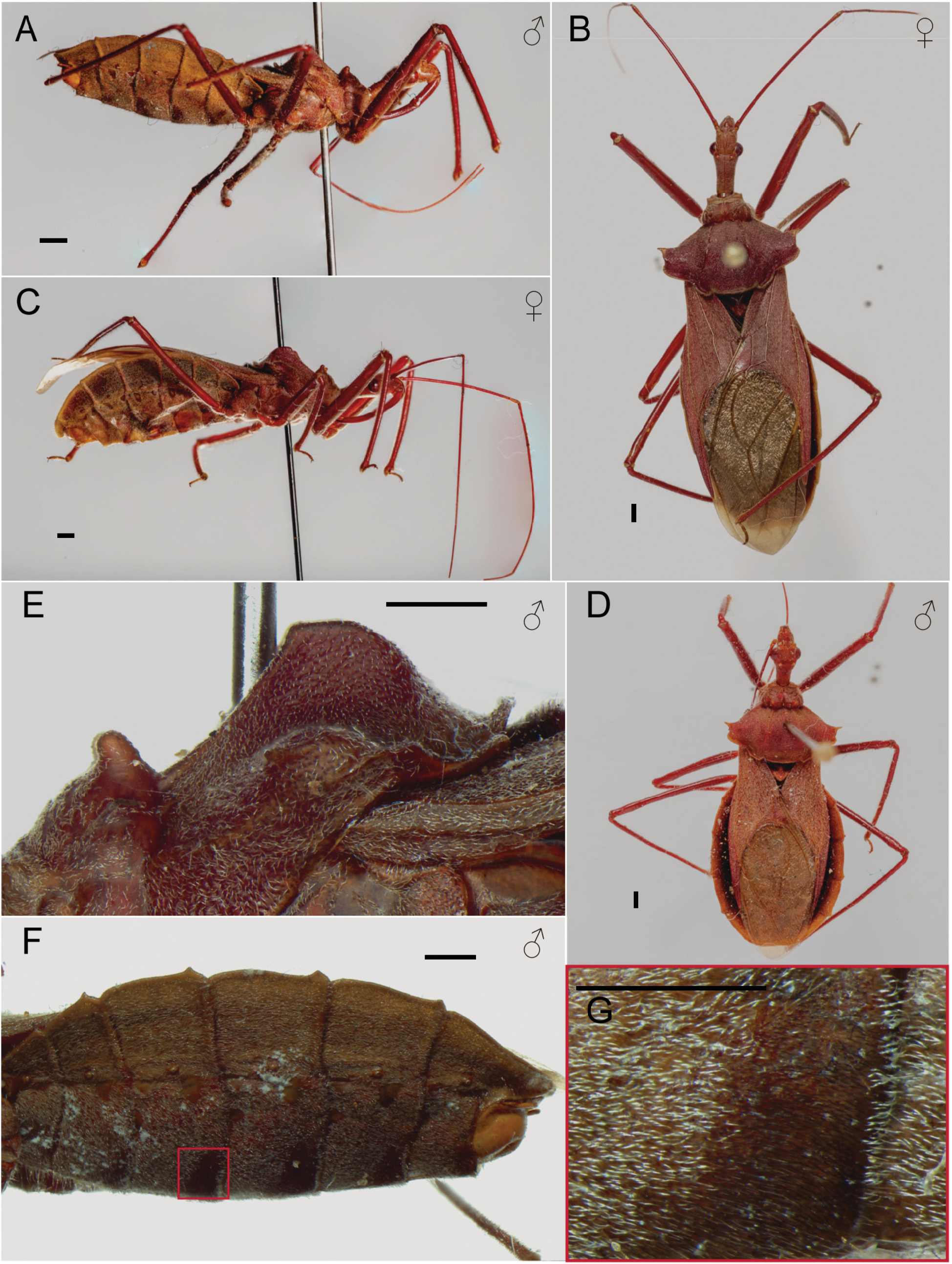

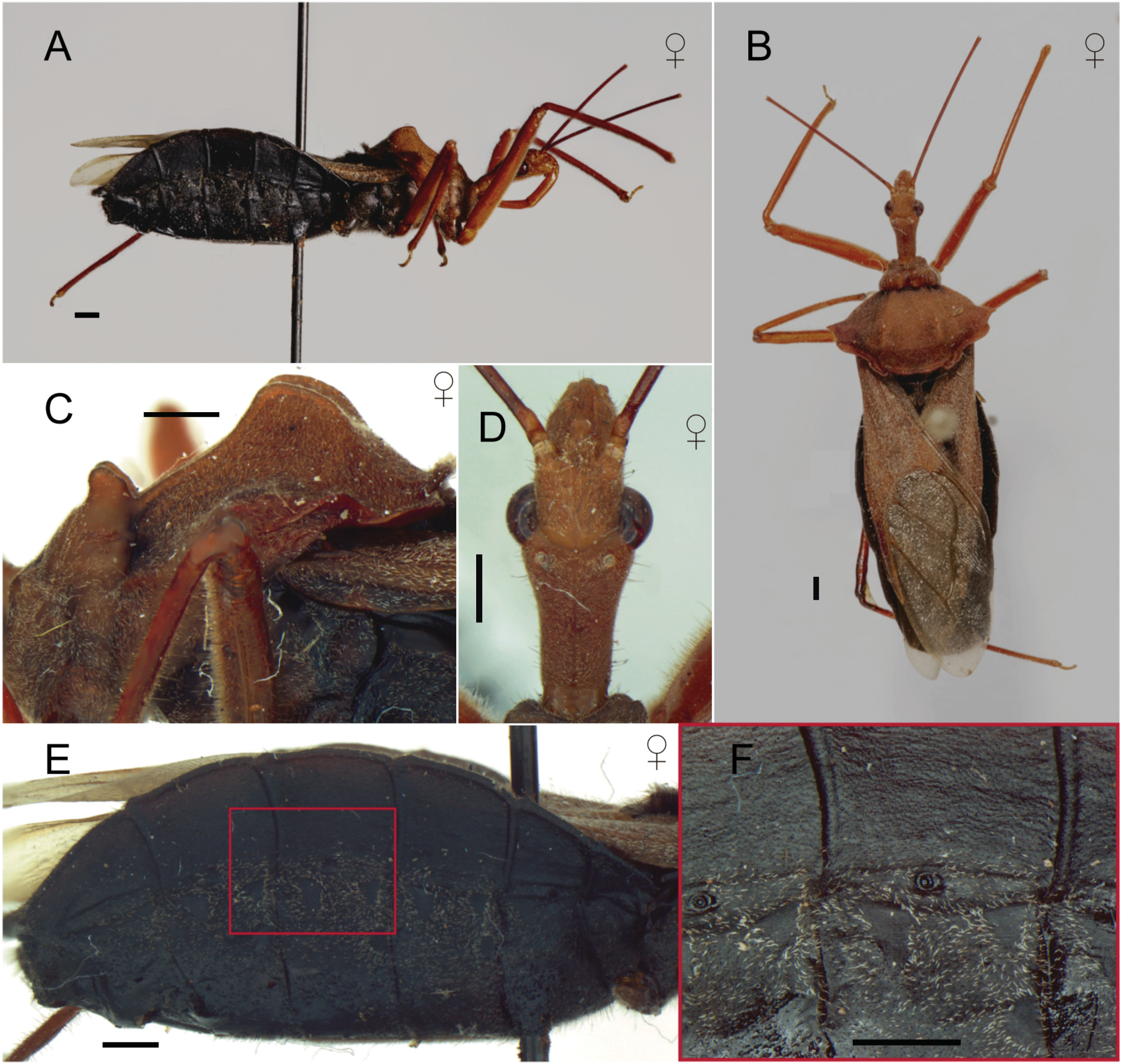

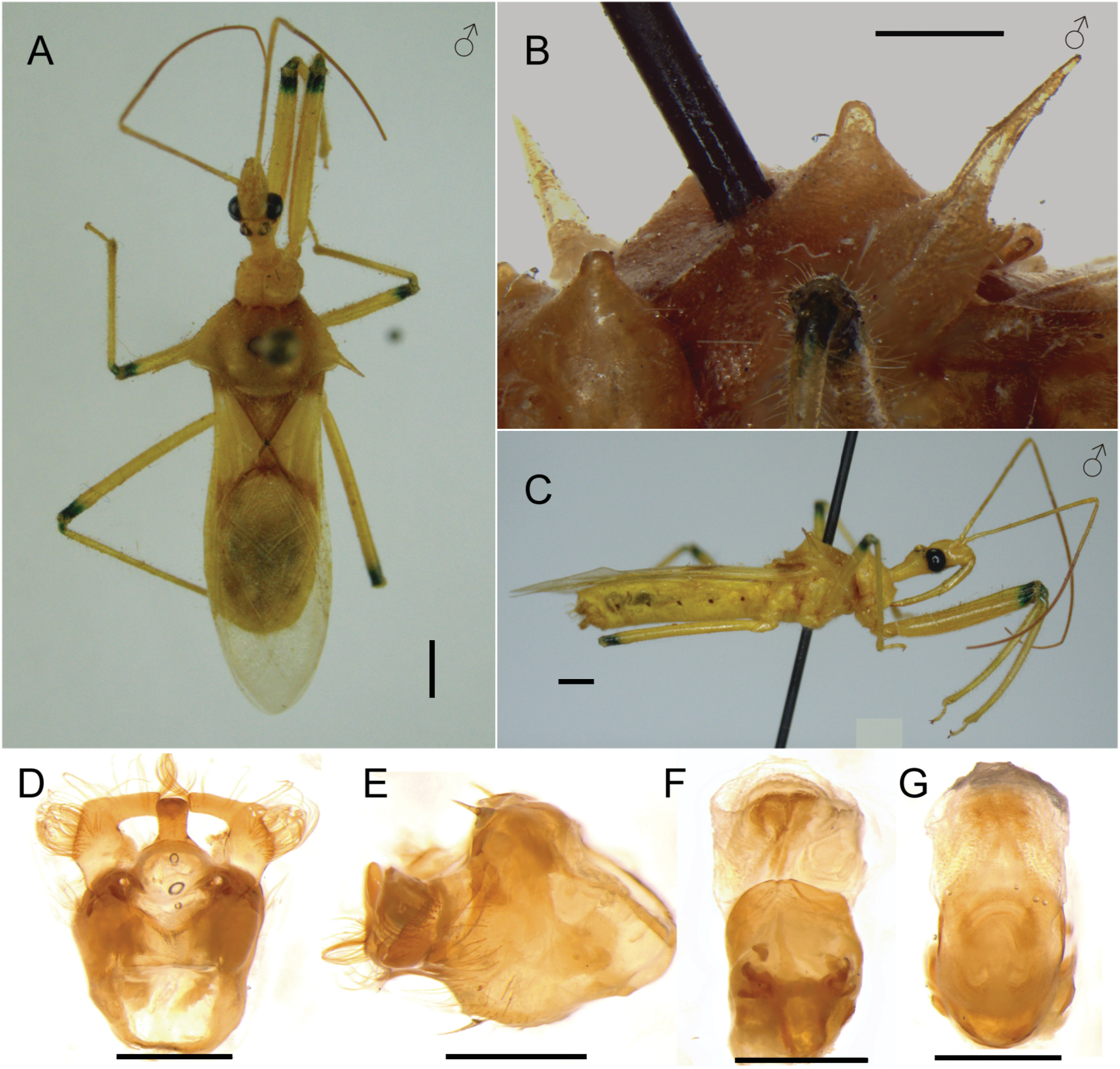

Diagnosis. Distinguished among all Neotropical Harpactorini genera by the following combination of characters: head elongate, length/width ratio 2.3; disc of the anterior lobe of the pronotum with a pair of discal tubercles ( Figs 2A–B View Fig ; 5E–F View Fig ; 7E View Fig ; 9E–F View Fig ; 11F View Fig ), each posteriorly connected to the submedial longitudinal carinae on the posterior pronotal lobe; submedial carina on posterior lobe rises prominently on the discal area forming a laterally compressed elevation ( Figs 2B View Fig ; 15E View Fig ), which have its dorsal area truncated or rounded; the posterior margin of the pronotum have a pair of paramedial lobes ( Figs 2A View Fig ; 13D View Fig ; 19B View Fig ), each with its lateral margin entire and curved, and the margin between the lobes (in front of the scutellum) from slightly to strongly curved; the humeral angle of the pronotum is rounded, and anterior to it there is a laterally directed process, the posterolateral process ( Fig. 2A View Fig ); the mesopleura has a tubercle (the “plica” of authors); the connexivum is strongly protruding laterally on the abdomen ( Figs 7B, D View Fig ; 15B, D View Fig ), the connexival margins range from being almost straight ( Figs 7C View Fig ; 9C View Fig ) to strongly rounded lobes ( Figs 15A, C View Fig ). Males have the medial process of the pygophore (mpp) almost cylindrical in cross section, short, directed posteriorly at about 45 degrees, slightly to greatly widened basally, and with a small subapical hook-like posteriad projection ( Figs 3A–B View Fig ); the parameres (pa) are long, reaching the medial process, narrow, slightly enlarged apically and curved basally ( Figs 6A, C View Fig ; 8A, C View Fig ; 10A, C View Fig ); the phallosoma has the dorsal phallothecal sclerite (dps) ovoid with its margin broadly rounded ( Figs 10F View Fig ; 14F View Fig ); the endosoma has a pair of elongated basal dorsolateral lobes (bdl), a small distal dorsal lobe (ddl) beset with microtrichia, a pair of small distal lateral lobes (dll), a bilobed distal ventral lobe (dvl), and a pair of lateral lobes (ll) ( Figs 3C–E View Fig ). Females have the gonocoxa 8 with an emargination on the posterior margin ( Fig. 24A View Fig , red arrow); the bursa copulatrix has long and wide projecting lateral lobes (lbs) which are as long as the length of the bursa ( Figs 26 View Fig ; 27 View Fig ), anterior dorsal region with a dorsal semi-sclerotized fold and a ventral pair of folds, usually with a U-shaped sclerotization (usp) ( Fig. 28A View Fig ).

Biology. Individuals of Montina are generally found on shrubs or low vegetation ( Fig. 1 View Fig ) and are common in agricultural areas. All examined specimens were collected manually or with an entomological net, which suggests that other types of collecting methods may not be very effective. The biology and natural history of the species are poorly known, only being documented aspects of the predatory capacity, life cycle, and description of immatures of M. confusa ( BUENO & BERTI FILHO 1984a, b, 1987; DELLAPḖ et al. 2002; FREITAS 1994, 1995).

Montina has also been reported as a natural predator of agricultural pests. Montina confusa is a common predator of Lepidoptera larvae in Eucalyptus plantations ( ZANUNCIO et al. 1993, 1994) and of other pests in different crops in Brazil (e.g., TREVISAN & MENEGUETTI 2012). Similarly, in Colombia unidentified species of Montina has been documented as predators of insect pests of soybean, corn, and other crops (e.g., AYALA et al. 2013, GUEVARA & JIMḖNEZ 2018, LEṒN MARTÍNEZ & GUEVARA AGUDELO 2006). Thus, it is very important to adequately document the species to help plan future pest management programs that are willing to include Montina species in their strategies.

Differential diagnosis. The original description of Montina is short and not very detailed ( AMYOT & SERVILLE 1843); however, it mentions two important characters, the laterally protruding abdomen, and a pair of tubercles on the anterior lobe of the pronotum connected with a submedial longitudinal carina. These characters are shared with Ploeogaster . Given the extreme similarity between these two taxa we have based our hypothesis of the generic limits of Montina on the study of photographs of the lectotype and paralectotype of Reduvius sinuosus Lepeletier & Serville, 1825 ( Fig. 38 View Fig ) (NHMW) (see below), and numerous Colombian specimens of both Ploeogaster and Montina . We thus propose novel characters to help delimit the two genera ( Table 1 View Table 1 ).

The presence of a pair of prominent tubercles on the anterior pronotal lobe that are continued posteriorly by a longitudinal submedial carina is a common feature in both genera. The tubercles of the anterior lobe of the pronotum have no marked differences in both genera, as they can be small acute tubercles or subcylindrical tubercles with a rounded apex. The structure of the posterior pronotal lobe between the two genera, on the other hand, shows a marked difference that has not been documented before. In Montina , the longitudinal submedial carina is slightly compressed laterally, and has an elevated portion on the discal area of the posterior lobe, this elevation is dorsally truncated or slightly rounded ( Figs 21E View Fig ; 23C View Fig ); whereas in Ploeogaster the longitudinal submedial carina is less compressed, and the elevated portion on the discal area has a tubercle with a rounded apex ( Fig. 4B View Fig ).

The posterior margin of the pronotum presents in Montina a pair of paramedial lobes, which have an entire lateral margin ( Figs 2A View Fig ; 7B View Fig ; 13D View Fig ), whereas in Ploeogaster these lobes have the lateral margin deeply emarginated giving the impression of being almost bilobed ( Fig. 4A View Fig ). In both genera the shape of the posterior margin connecting the paramedial lobes range from being almost straight to strongly curved, so we consider this a variable character between the genera which might be species specific. In Montina , the posterolateral process of the pronotum, which is located anterior to the humeral angles, is small and no longer than its base width ( STÂL 1867), sometimes being a blunt tubercle ( Figs 5D View Fig ; 13D View Fig ). In Ploeogaster , the posterolateral process is a conspicuous acute projection directed laterally and always longer than its base, giving the appearance of a sharp process ( Fig. 4A View Fig ).

Another unexplored character is the structure of the fore legs. In Montina , the fore femur is cylindrical on its entire length with its ventral margin nearly straight, and the fore tibia is also straight ( Figs 5A, C View Fig ). Ploeogaster , on the other hand, has the fore femur wider near the middle with its ventral margin slightly curved ventrally, being thus the fore tibia similarly curved ( Fig. 4C View Fig ). It also seems that the profemur in Ploeogaster is much wider than the mesofemur ( Fig. 4A View Fig ) when compared to the width ratio between the pro- and mesofemur of Montina ( Figs 5B, D View Fig ), but this must be tested with accurate measurements in several species.

The male genitalia are also useful to delimit these genera. In Montina the medial process of the pygophore (mpp) is almost cylindrical, reclined, directed posteriorly at about 45 degrees, short and narrow, sometimes widened at the base, and with a small hook-like projection directed posteriad ( Figs 3A–B View Fig ; 8A–C View Fig ). In Ploeogaster , on the other hand, the mpp is flattened antero-posteriorly, having thus a laminar form, being much longer than in Montina , of subparallel margins, and directed almost vertically ( Figs 4D, E View Fig ). Furthermore, the parameres in Montina are narrow, slightly enlarged apically, and curved basally ( Figs 8A View Fig ; 10A View Fig ; 16A View Fig ), whereas in Ploeogaster they are usually wide and enlarged medially ( Fig. 4D View Fig ).

The structure of the male genitalia is usually useful for species delimitation in Harpactorini (e.g., FORERO et al. 2008; ZHANG et al. 2016). In Montina , male genitalia are rather uniform, only with small differences between species. Particularly, the male aedeagus has only slight differences among species. Nonetheless, the structure of the medial process of the pygophore (mpp) is clearly different among species (e.g., Figs 6A–C View Fig ; 10A–C View Fig ; 14A–C View Fig ). Other characters such as the shape of the margin of the connexivum, color patterns, and the vestiture of the ventral laterotergites and sternites of the abdomen are more conspicuous and are used here as the primary characters to delimit the species.

A character that has been used to separate Montina and Ploeogaster is the structure of the connexivum ( AMYOT & SERVILLE 1843, STÂL 1867). Traditionally has been indicated that each of the connexival segments are forming distinct rounded lobes in Montina in opposition to straight margins in Ploeogaster . However, this is not always the case, because in some Montina species the margin of the connexivum is almost straight ( Figs 7A, C View Fig ; 9A, C View Fig ; 11C View Fig ; 19C View Fig ; 21A, C View Fig ; 23A View Fig ) and it could be nearly lobate in some Ploeogaster species. Therefore, the shape of the margin of the connexivum seems an unreliable character to separate these two genera. Despite this, having a lobate margin of the connexivum could help to recognize certain Montina species.

The value of the aforementioned characters to delimit the two genera is congruent with the results of the phylogenetic analysis of ZHANG & WEIRAUCH (2014). Among the Neotropical clades recovered in their analysis, there is one monophyletic group containing species that we positively ascribe to Montina , and another one which contains species that we identify as Ploeogaster . This assessment was based on the examination of images of their voucher specimens (http://research.amnh.org/pbi/heteropteraspeciespage/, searched for each taxon and the RCW numbers used in ZHANG & WEIRAUCH 2014) and verified against the proposed characters mentioned above to distinguish Montina from Ploeogaster . Although these two groups are not sister lineages in their final topology, as would be the expectation based on the very similar morphology of the pronotum and abdomen, the low support values indicate that the relationships presented must be viewed as unresolved at best, therefore allowing the possibility that these two clades might be sister groups. Furthermore, the specimen UCR_ENT 00001516 (RCW_ 636 in their analysis) that is nested within Ploeogaster species correspond to what has been described as Cidoria Amyot & Serville, 1843 , a monotypic genus known from French Guiana (MALDONADO 1990). In Cidoria , the pronotum exhibit the same pronotal structure as species of Ploeogaster , particularly the presence of a pair of discal tubercles on the posterior lobe of the pronotum and the strongly emarginate paramedial lobes on its posterior margin. The only remarkable feature of Cidoria is the strongly curved medial posterior margin of the pronotum between the paramedial lobes, thus covering almost completely the scutellum in dorsal view, but as indicated above, the shape of the posterior pronotal margin is a variable feature in both Ploeogaster and Montina . Future studies might conclude that Cidoria is congeneric with Ploeogaster .

Distribution. Costa Rica, Panama, French Guiana, Guyana, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru (CHAMPION 189; GIL- SANTANA 2019; MALDONADO 1990; STÂL 1859, 1865, 1867, 1872). Newly recorded from Colombia.

Key to the known species of Montina View in CoL (for Spanish translation see the Appendix)

1 Connexival margin, at least segments 4 and 5, noticeably lobed ( Figs 13A, C View Fig ; 15C View Fig ; 19A View Fig ); if slightly lobed ( Figs 19C View Fig ; 17A View Fig ) then general coloration orange with head and legs black or brown ( Figs 19A–D View Fig ), or general coloration pale brown with ventral laterotergites dark with a pale-yellow oblique band on the posterior margin of segments 2–6 ( Figs 17A, C View Fig ). .......................... 2

– Connexival margin straight or at most slightly lobed ( Figs 7A View Fig ; 9A View Fig ; 11D View Fig ; 21A, C View Fig ; 23A View Fig ); if segments 4 and 5 are slightly lobed ( Fig. 11A View Fig ) then general coloration is brown, with ventral laterotergites dark without pale contrasting areas ( Figs 11A, B View Fig ). ............................... 8

2 Ventral laterotergites dark without any pale contrasting areas ( Figs 38A–B View Fig ). ..................................................... ................ M. sinuosa ( Lepeletier & Serville, 1825) View in CoL

– Ventral laterotergites dark with red or yellow contrasting areas. .................................................................. 3

3 Ventral laterotergites dark with contrasting paleyellow areas, either an oblique band on the posterior margin of segments 2–6 ( Figs 15A, C View Fig ; 17A, C View Fig ), or on the dorsal margin of segments 2–7 ( Fig. 35A View Fig ). ........ 4

– Ventral laterotergites with a red band on the dorsal margin of each segment, sometimes not very conspicuous ( Figs 5A, C View Fig ; 13A, C View Fig ; 19A, C View Fig ), but contrasting areas never yellow. ................................................... 6

4 Connexival margin not deeply lobed, with a short, acute process on the posterior half of segments 2–6, more acute in males ( Fig. 17A View Fig ); general coloration pale brown ( Figs 17B, D View Fig ). .......... M. ruficornis ( Fabricius, 1803)

– Connexival margin deeply lobed on segments 4–5 ( Figs 15A, C View Fig ; 38B View Fig ); general coloration dark to black. ........ 5

5 Pronotum pale-yellow, densely setose ( Fig. 15E View Fig ); pale--yellow bands present on the posterior margin of each connexival segment ( Figs 15A–D View Fig ). ............................. ................................................. M. lobata Stål, 1859 View in CoL

– Pronotum dark red, with sparse setae ( Fig. 35B View Fig ); dorsal margin of connexivum with a pale-yellow, narrow band ( Figs 15A–D View Fig ). ................ M. nigripes Stål, 1859 View in CoL

6 Connexival margin with segments 4–6 deeply lobed (both males and females), without a conspicuous acute process on each segment ( Figs 5A, C View Fig ); discal tubercles of the anterior lobe of the pronotum not well developed ( Figs 5E–F View Fig ). .......................................................... ............... M. calarca Mejía-Soto & Forero sp. nov.

– Connexival margin only with segments 4 and 5 lobed, posterior margin of each segment oblique, with a short, acute process on the posterior half ( Figs 13A, C View Fig ; 19A, C View Fig ); discal tubercles of the anterior lobe of the pronotum subconical and well developed ( Figs 13E, F View Fig ; 19E, F View Fig ). ............................................................................. 7

7 Head red ( Figs 13B, D, G View Fig ); posterior margin of pronotum red; proximal portion of the corium red ( Figs 13B, D View Fig ). .......... M. gladiator Mejía-Soto & Forero sp. nov.

– Head black ( Figs 19B, D View Fig ); posterior margin of the pronotum usually with a transverse dark band connecting the bases of the paramedial lobes; proximal portion of the corium dark ( Figs 19B, D View Fig ). .................................... .......................................... M. scutellaris Stål, 1859 View in CoL

8 Forewing membrane with a conspicuous hyaline medial area ( Fig. 32B View Fig ). .......... M. fenestrata ( Stål, 1867) View in CoL

– Forewing membrane with uniform coloration ( Figs 21B View Fig ; 23B View Fig ). ................................................................ 9

9 Ventral laterotergites uniformly black, with scattered black, erect setae ( Figs 23E–F View Fig ); abdominal sternites entirely black, with decumbent, silver setae ( Fig. 23F View Fig ). .......... M. tikuna Mejía-Soto & Forero sp. nov.

– Ventral laterotergites with contrasting coloration ( Figs 7A, C View Fig ; 9A, C View Fig ), if apparently with homogenous coloration ( Figs 11A, C View Fig ; 21A View Fig ) with numerous decumbent setae and no erect setae; abdominal sternites not entirely black, with silver or black erect setae. .................... 10

10 Overall dorsal coloration and legs red ( Figs 7B, D View Fig ; 21B, D View Fig ). .................................................................. 11

– Overall dorsal coloration and legs brown to pale brown ( Figs 9B, D View Fig ; 11B, D View Fig ). ............................................. 12

11 Dorsal laterotergites with segments 2–4 mostly black, 5–7 black with a broad and conspicuous yellow or orange dorsal band increasing in size toward the posterior segments ( Figs 7B, D View Fig ), tubercle of the anterior pronotal lobe straight, constricted near the middle and markedly globose apically ( Fig. 7E View Fig ). .......................... ........................................... M. confusa ( Stål, 1859) View in CoL

– Dorsal laterotergites with segments 3–7 black with a narrow and uniform orange band on their lateral margin ( Figs 21B, D View Fig ), tubercle of anterior pronotal lobe slightly curved anteriad, not constricted near the middle ( Fig. 21E View Fig ). ...................... M. testacea ( Stål, 1859) View in CoL

12 Ventral laterotergites mostly dark brown ( Figs 11A, C View Fig ). ......................................... M. fumosa ( Stål, 1867) View in CoL

– Ventral laterotergites with a dorsal, broad, pale-yellow band contrasting with the black ventral area (males on segments 4–5 with black reaching dorsal margin) ( Figs 9A, C View Fig ). ................................ M. distincta ( Stål, 1859) View in CoL

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Montina Amyot & Serville, 1843

| Mejía-Soto, Andrés, Forero, Dimitri & Wolff, Marta 2022 |

Montina

| WALKER F. 1873: 93 |

| STAL C. 1872: 74 |

Aristippus: STÂL (1867)

| STAL C. 1867: 48 |

| STAL C. 1867: 299 |

Aristippus Stål, 1865: 48

| STAL C. 1865: 48 |

Montina: STÂL (1859)

| ZHANG J. & WEIRAUCH C. & ZHANG G. & FORERO D. 2016: 540 |

| ZHANG G. & WEIRAUCH C. 2014: 341 |

| MALDONADO J. 1990: 234 |

| PUTSHKOV V. G. & PUTSHKOV P. V. 1988: 115 |

| LETHIERRY L. F. & SEVERIN G. 1896: 195 |

| WALKER F. 1873: 91 |

| STAL C. 1872: 73 |

| STAL C. 1865: 48 |

| STAL C. 1859: 197 |

Ploeogaster

| STAL C. 1872: 73 |

| STAL C. 1859: 197 |

Montina

| AMYOT C. J. B. & SERVILLE A. 1843: 363 |