Giraffa camelopardalis, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719821 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719825 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039F7D71-A96C-AD1D-0D12-FE207077DB5B |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Giraffa camelopardalis |

| status |

|

Girafte

Giraffa camelopardalis View in CoL

French: Girafe / German: Giraffe / Spanish: Jirafa

Other common names: Nubian Giraffe (camelopardalis), Kordofan Giraffe (antiquorum), Masai Giraffe (tippelskirchi), Reticulated/ Somali Giraffe (reticulata), Rothschild Giraffe (rothschildi), Smoky/Angolan Giraffe (angolensis), South African Giraffe (giraffa), Thornicroft/Rhodesian Giraffe (thornicrofti), West African / Nigerian Giraffe (peralta)

Taxonomy. Cervus camelopardalis Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

Sennar, Sudan.

It appears from genetic studies that Giraffes fall into three groups: West African Giraffes (peralta); North African Giraffes (antiguorum, reticulata , rothschildi, thornicrofti, and probably camelopardalis ); and southern African Giraffes (angolensis and guraffa). The “Masai Giraffe,” tippelskirchi , exhibits similarities with both the southern and the northern groups. Genetic differences, ranging from 0-15% to 6-9%, are below those required for the establishment of distinct species. Nine regional variants are currently recognized as subspecies, all of which interbreed.

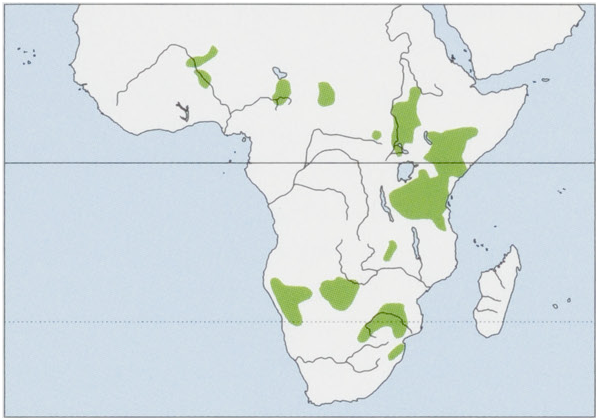

Subspecies and Distribution.

G. c. camelopardalisLinnaeus, 1758 — ESudanandWEthiopia.

G. c. angolensisLydekkcr, 1903 - NNamibia, SZambia, NBotswana, andNWZimbabwe.

G. c. antiquorumJardine, 1835 - SChad, Genua] AfricanRepublic, andNEDRCongo.

G. c. giraffaSchreber. 1784 - SWMozambique, SZimbabwe, andSouthAfrica.

G. c. peraltaThomas, 1898 - WAfrica.

G. c. reticulataDeWinton, 1899 - SEthiopia, SWSomalia, andNKenya.

G. c. rothschildiLydekker, 1903 - SSudan. NUganda, andWKenya.

G. c. tippelskirchiMatschie, 1898 - SKenyaandTanzania.

G. c. thornicrofti Lydekker, 1911 -Zambia (Luangwa Valley). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 350-480 cm,tail 76-110 cm, height to the crown 450-600 cm; weight 1800-1930 kg (males) and 450-1180 kg (females). Adult males are larger than females. Colored hair patches are separated by yellow-white bands and vary in the regional variants. Patches contain large active sweat glands and a unique arrangement of blood vessels, suggesting they act as thermal windows through which to dissipate heat. Pigmentation of the skin is uniformly dark gray. The extraordinary shape results from elongation of the neck skeleton and of the lower leg bones. Elongation of the legs is associated with thickening of the bone wall to provide strength and of the neck by uniform lengthening of all seven cervical vertebrae. Elongation of the skeleton is rapid and demands the accumulation of large amounts of calcium and phosphorus. Giraffe anatomy has necessitated physiological adaptations; e.g. systemic blood pressure is twice that for similar sized mammals. The cells of the left ventricular and interventricular walls of the heart are enlarged, their thickness linearly related to neck length. Simultaneous enlargement of artery and arteriole walls provides resistance to blood flow. This appears to be a coordinated reflex response that maintains blood flow to the brain to protect Giraffes from fainting when they raise their heads after drinking, and to prevent peripheral oedema in the legs. Valves in the jugular vein prevent regurgitation of blood returning to the heart into the jugular vein. The long trachea is significantly narrower than in similar-sized mammals, limiting increases in dead space. Giraffe skulls feature paired subconical ossicones, which resemble short, blunt horns, arising from the top of the brain case. Female skulls are smoother and lighter than those of males. Bulls may have another median horn, which is a male secondary sexual characteristic, arising from the forehead between the eyes.

Habitat. Giraffes are thought to have coevolved with acacia trees in savanna biomes throughout Africa but their occurrence is now discontinuous. They have never occurred in the tropical rain forest of the Congo River Basin.

Food and Feeding. Exclusively browsers of dicotyledons, their preferred browse is mainly various species of Acacia. Four species of Acacia and four species of Combretum predominate in their diet, as these are rich in protein and calcium to support growth of their large skeleton. Bulls browse at higher levels than cows. Giraffes are water dependent but can survive for long periods without drinking water, obtaining their daily water needs from succulent browse. Giraffids are foliovores, selecting succulent foliage, and have an efficient digestive system compared to that of grazers, which eat monocotiyledons. The Giraffe stomach is half the size of that of African buffalo (Syncerus sp.).

Breeding. Giraffes are aseasonal breeders. Females become sexually mature at 4-5 years of age. Gestation lasts about 450 days; birth mass is around 100 kg. At birth shoulder height is 1-50-1-80 m. Calves are precocial, seeking the first suckle within an hour of birth. Calves lie isolated for up to three weeks. Lactation lasts for around twelve months. Calf mortality rate is up to 75% in the first year. In captivity Giraffes can live to 36 years of age. Bulls reach sexual maturity at 2-5—4 years of age but need to pass a behavioral threshold in the wild to compete with mature bulls.

Activity patterns. Giraffes rest in the shade during the hottest time of day. Males orient their bodies towards the sun depending on whether they need to reduce or gain radiant heat, but females and calves select shade. They bend their heads backwards towards the body during deep sleep. They gallop in an ungainly manner, swinging the two legs on each side in unison.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Giraffes are mainly diurnal, and most active hours are spent feeding. Their gait is unusual in that both legs on one side swing in unison making their walk ungainly. Their maximum speed is about 56 km /h, and they can jump fences 1-5 m high. Giraffes are not territorial and home ranges vary from 25 km? to 160 km?. Major rivers are barriers, as Giraffes cannot swim and do not easily cross flowing rivers. Strong social bonds are lacking, and herds, mostly of females and their young, rarely consist of the same individuals for more than a few days.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Giraffes were provisionally classified as not threatened by IUCN, as the population in the wild consisted of at least 100,000 individuals and their distribution was widespread. However the West African subspecies peralta is now classified as Endangered, its numbers and range having fallen sharply. Previously its range was from Senegal to Lake Chad, but currently the only viable surviving population in this entire area consists ofless than 200 individuals in south-western Niger, with a range of about 15,000 km? Recent population estimates indicate a downward trend in numbers, which might eventually result in a different category. Some populations remain stable, some are increasing, and others are decreasing. Further studies aimed at resolving the taxonomic status of the various subspecies and populations will also allow better assessment of conservation status. In southern Africa, Giraffe has been reintroduced to many parts of the range from which they were previously eliminated, and it has been introduced into Swaziland.

Bibliography. Aschaffenburg et al. (1962), Badlangana et al. (2009), Berry (1978), Bigalke (1951), Bond & Loffell (2001), Bredin et al. (2008), Brown et al. (2007), Cameron & Du Toit (2005, 2007), Cerling et al. (2004), Ciofolo & Pendu (1998), Dagg (1962, 1971), Dagg & Foster (1976, 1982), Fennessy & Brown (2010), Fennessy et al. (2001), Foster & Dagg, (1972), Gallagher et al. (1994), Hall-Martin & Skinner (1978), Hall-Martin, Skinner & Hopkins (1978), Hall-Martin, Skinner & Smith (1977), Hamilton (1973), Harris (1976), Hugh-Jones et al. (1978), Jacobson et al. (1986), Kidd (1900), Kok (1982), Kok & Opperman (1980), Kuntsch & Nel (1990), Langman (1977, 1978), Langman et al. (1982), Le Pendu et al. (2000), Leuthold (1979) Leuthold & Leuthold (1972, 1978), Lightfoot (1978), Lydekker (1904), Madden & Young (1982), Miller (1994, 1996), Mitchell (2009), Mitchell & Hattingh (1993), Mitchell & Skinner (1993, 2003, 2004, 2009), Mitchell, Bobbitt & Devries (2008), Mitchell, Maloney et al. (2006), Mitchell, van Schalkwyk & Skinner (2005), Mitchell, van Sittert & Skinner (2009a, 2009b), Pellew (1983a, 1983b, 1984a, 1984b), Pienaar (1969), Pilgrim (1911), Pratt & Anderson (1982), Ridewood (1904), Robin et al. (1960), Scheepers (1992), Shortridge (1934), Simmons & Scheepers (1996), Singer & Boné (1960), Skinner & Chimimba (2005), Skinner & Hall-Martin (1975) Skinner & Smithers (1990), Solounias (1999), Spinage (1968, 1993), Van Aarde (1976), Van Sittert et al. (2010), Van Schalkwyk et al. (2004), Von Linnaeus (1758), Wyatt (1971), Young & Okello (1998).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Giraffa camelopardalis

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

camelopardalis

| Linnaeus 1758 |