Heliothraupis oneilli, Lane, Aponte, Rheindt, Rosenberg, Schmitt, and Terrill, 2021

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ornithology/ukab059 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5710704 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039F9B29-4213-A008-FD94-4ED89C5E9F28 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Heliothraupis oneilli, Lane, Aponte, Rheindt, Rosenberg, Schmitt, and Terrill |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Heliothraupis oneilli, Lane, Aponte, Rheindt, Rosenberg, Schmitt, and Terrill View in CoL , sp. nov.

English name: Inti Tanager

Spanish name: Tangara Inti

Holotype. MNK-AV 6350 ; BOLIVIA: dept. La Paz; Prov. Franz Tamayo, loc. ANMI. Madidi , valle del Machariapo , ca. 33 km NW Apolo , 14 ° 26.4’S, 68 ° 31.9’W, elevation 960 m. Male. Tissue sample: LSUMZ B-95316. 27 January 2019. Collected and prepared by Miguel Angel Aponte Justiniano, field catalog number 1189. Associated sound recordings: ( ML 238445 ) GoogleMaps .

Diagnosis of species. The combination of several distinct plumage characters is unique within the family (see Frontispiece). The brilliant yellow plumage with the contrasting black supercilium and pinkish bill of the male is more likely to remind one of an African or Asian Oriolus oriole (e.g., Oriolus auratus , African Golden Oriole, Oriolus chinensis , Black-naped Oriole, or Oriolus tenuirostris , Slender-billed Oriole) before any Neotropical species comes to mind! The burnt orange crest is similar to that of Tachyphonus delatrii . This crest differs from that of male Trichothraupis melanops in that it is never hidden by the lateral crown feathers. The mostly yellow female is less distinctive, perhaps most likely confused with a juvenile Schistochlamys melanopis (Black-faced Tanager), or a female Piranga olivacea (Scarlet Tanager), P. flava (Hepatic Tanager), or P. rubra (Summer Tanager), but is brighter yellow than any of these, with a proportionately longer tail than Piranga , and with at least some bright orange or pink on the bill.

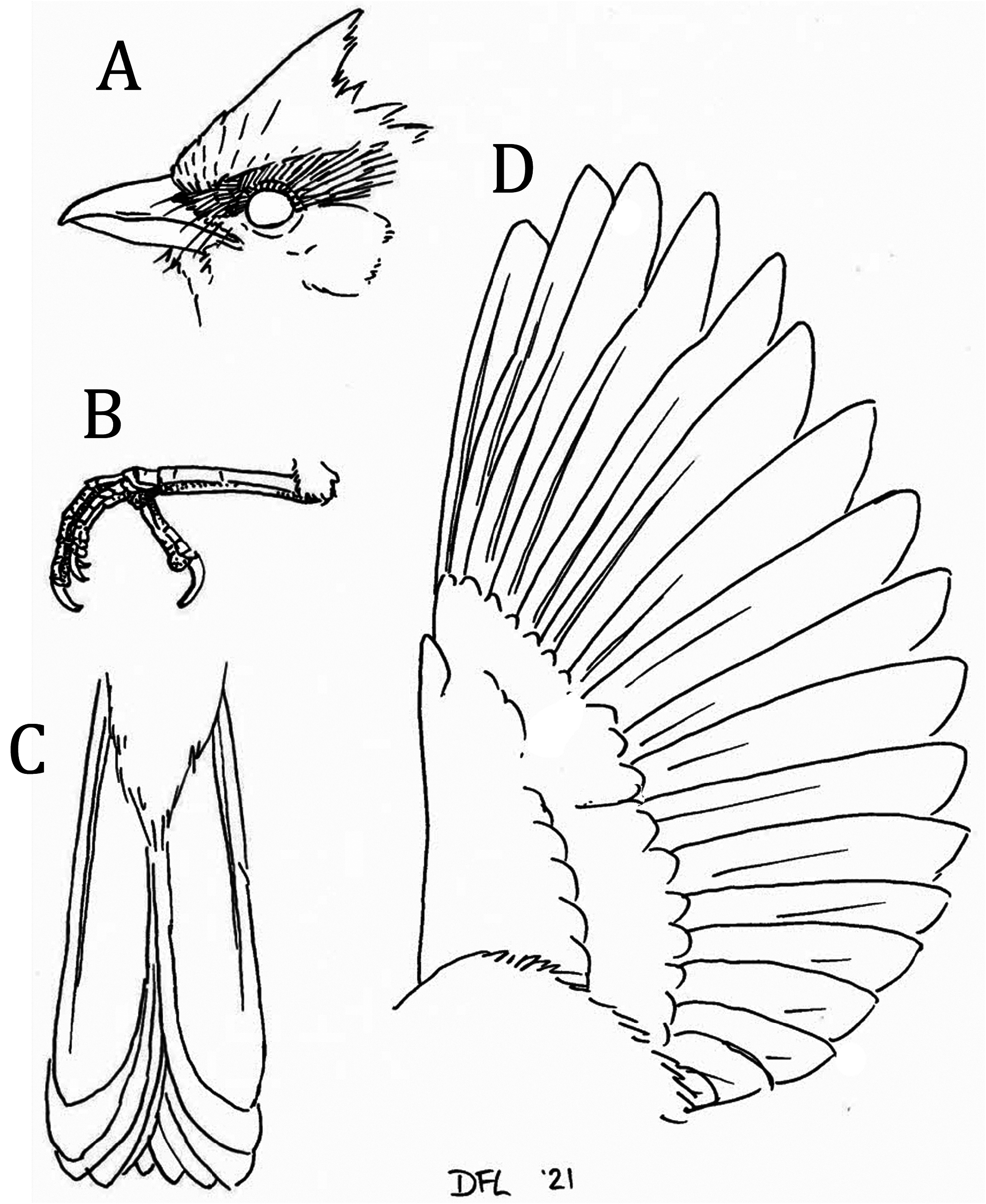

Description of holotype. Plumage colors were scored using Munsell (no date), judged under a mixture of natural and fluorescent lighting. Forehead and crown are burnt orange closest to 7YR 6/12; the crown feathers behind the center of the crown are longer, forming a short, shaggy crest. Aline of blackish feathering extends from the nares, the lores, justoverthe eyes, andalongthe sidesof the crown above the auriculars, ending at the rear of the auriculars. The feathering between the eye and the rictus, as well as the lower half of the orbital feathering are yellow, closest to 2.5Y 8.5/12. Auriculars are a greenish-yellow closest to 5Y 7/12. Body feathers from nape to upper tail coverts are a uniform olive closest to 7.5Y 5/8. Lesser, median, and greater secondary and primary wing coverts also closest to 7.5Y 5/8; small feathers along leading edge of wing from “wrist” to base of outermost primary yellow, closest to 5Y 8.5/12. Rectrices and remiges are also olive, darkest near feather shaft (closest to 7.5Y 4/6), becoming paler towards margins (remix margins visible on closed wing), closest to 7.5Y 5/8, inner tips of primaries darkest, closest to 5Y 3/4. Axillaries and underwing coverts yellow, closest to 5Y 8.5/12. Undersides of primaries dusky (closest to 5Y 4/2), innermost portion of inner web becoming most contrastingly yellow (closest to 5Y 8/8). Primaries 8-4 emarginated ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ). Malar, chin, throat, and center of breast saffron yellow, closest to 2.5Y 8/16, becoming a medium yellow (closest to 5Y 8.5/14) on belly and undertail coverts. Sides of breast and flanks olive-yellow, closest to 5Y 6/10. Label information: Weight 21.8 g; Length 18 cm; Wingspan 26.5 cm; Bill orange; Tarsi, toes yellowish brown; No wing, tail, or body molt; Medium fat; Left testis 7 x 5 mm; Skull 100% ossified; Stomach contained seeds and insect remains; Collected by mist net; Voice recorded by MAA and also on 25 January by DFL (ML 238445).

Paratypes. MUSM 30068 , LSUMZ 195912 , 195915 , 195916 , 195921 , 195922 , 195925 , 195925 , B-95315 , MKN-AV 6349 , 6360 , 6361 , 6362 , 6363 , 6364 , 6365 , 6366 .

Description of paratypes. In addition to the holotype, another 16 paratype specimens of Heliothraupis exist. Fifteen of these are also males, 14 from within 10 km of the type locality, and collected between 22 and 26 December 2012 and 25–28 January 2019. One male, the firstspecimen that was collected on 9 June 2004, is from the Kosñipata road in Peru (MUSM 30068). None of these males differ noticeably from the holotype in plumage coloration or pattern. Although the crowns of some individuals appear very slightly scaled with darker orange tips to the crest feathers, others have more saturated orange-yellow on the center of the breast and undertail coverts. Of the 14 males taken in December, only 2 exhibited any molt: LSUMZ 195916 had all rectrices sheathed (presumably adventitious replacement). Of the 3 birds taken in January, 2 exhibited molt. MNK.AV. 6349 had asymmetrical wing (primaries 6 on both wings, and secondaries 2, 3 on left wing and 3 on the right wing sheathed) and tail (left rectrices 3, 4, right rectrices 2, 3 sheathed) molt and moderate body molt, and LSUMZ B-95315 had only asymmetrical tail molt (left rectrix 3, right 3–6 sheathed). An additional bird observed and photographed on 22–24 January 2019 had all rectrices sheathed. The Peruvian specimen (MUSM 30068), collected on 9 June 2004, had rectrices that were heavily worn, both primaries 6 and secondaries 1 sheathed, and it showed trace body molt; we conclude that the bird was beginning definitive prebasic molt.

We only collected 1 female, (LSUMZ 195925), taken 25 December 2012 fromone of the southernmostand highestelevation territories we encountered in 2012 (BOLIVIA: dpto La Paz, Machariapo Valley, 14°36’S, 68°27’W, 1,100 m), which differed from the males primarily in head and breast plumage. The forehead to nape of the female is olive, concolor with the remaining dorsal plumage, closest to 7.5Y 5/8. The lores and anterior portion of the orbit feathering are a pale greenish-cream closest to 7.5Y 8/8. Rear portion of orbit a pale yellow 5Y 8/8. The auriculars, rear portion of the supercilium, malar, and sides of neck are yellow-olive (5Y 7/10). Chin and throat a pale medium yellow (5Y 8.5/10). Aweakly defined broad ochraceousyellow band across the breast is closest to 2.5Y 7/12 with weak olive streaks, particularly towards sides of breast (closest to 7.5Y 7/12). Label information: Weight 29.1 g. Wingspan 251 mm. Iris dark brown. Mandible orange with dusky splotch. Maxilla dusky with orange around tomium and nares. Tarsi and toes gray. Shot in tropical deciduous forest with scrub (mate of LSUMZ 195924). Unshelled egg in oviduct 23 x 16 mm. No bursa of Fabricius. Skull 100% ossified. No molt. Stomach contained arthropod parts. We only observed one other female, on 26 December 2012, near the locality of the female specimen, which it resembled, except in having an entirely pinkish-orange bill.

Specimens examined. All known specimens of H. oneilli were reviewed and measured, as well as male specimens of several related taxa for comparison (Table 2): Trichothraupis melanops : LSUMZ 96899 , LSUMZ 196420 , LSUMZ 169146 . Eucometis penicillata pallida : LSUMZ 167782 , LSUMZ 167783 . Eucometis penicillata stictothorax: LSUMZ 138840 . Eucometis penicillata albicollis : LSUMZ 125305 , LSUMZ 183845 , LSUMZ 183846 . Eucometis penicillata penicillata : LSUMZ 83563 , LSUMZ 173154 , LSUMZ 110917 . Loriotus (Tachyphonus) cristatus : LSUMZ 133848 , LSUMZ 133844 , LSUMZ 133849 . Loriotus (Tachyphonus) rufiventer : LSUMZ 117481 , LSUMZ 116170 , LSUMZ 191773 .

Etymology. The species name oneilli is to honor our mentor, friend, and colleague, John P. O’Neill, whose efforts started the LSUMNS’s South American program, and who played an important role in directing much of the fieldwork over a period of over 40 years. John has shared his knowledge, kindness, generosity, and good humor with several generations of students at LSU, as well as with the greater birding and ornithological communities, particularly in Peru, and this has made him a beloved and treasured member of each. He is renowned for his ability to choose likely sites worthy of ornithological exploration, a skill that has been rewarded with his authorship of the descriptions of 15 new species (including 3 new genera) of birds. John has been an active element in the development of domestic ornithological study in Peru, a country that has become a second home to him, not least of which for being one of the progenitors of the field guide Birds of Peru, and assuring a Spanish edition was published in addition to English. He also provided financial and logistical support to the ornithological departments of MUSM and CORBIDI at key periods of the respective development of both Peruvian institutions and has participated tirelessly in efforts to engage young Peruvians in ornithological fieldwork. He embodies the spirit of inclusiveness and views each person who has worked alongside him in the process of conducting fieldwork as an equal, from the local camp assistants to fellow biologists to politicians and donors. The Peruvian government formally recognized his contributions to the development of ornithology and ecotourism in Peru through the 2008 Distinguished Service Merit Award. We cannot express how much John has meant to us as an inspiration in our own careers. Our proposed common name “ Inti ” is derived from the Quechua and Aymara word for “Sun” and thus parallels the genus name.

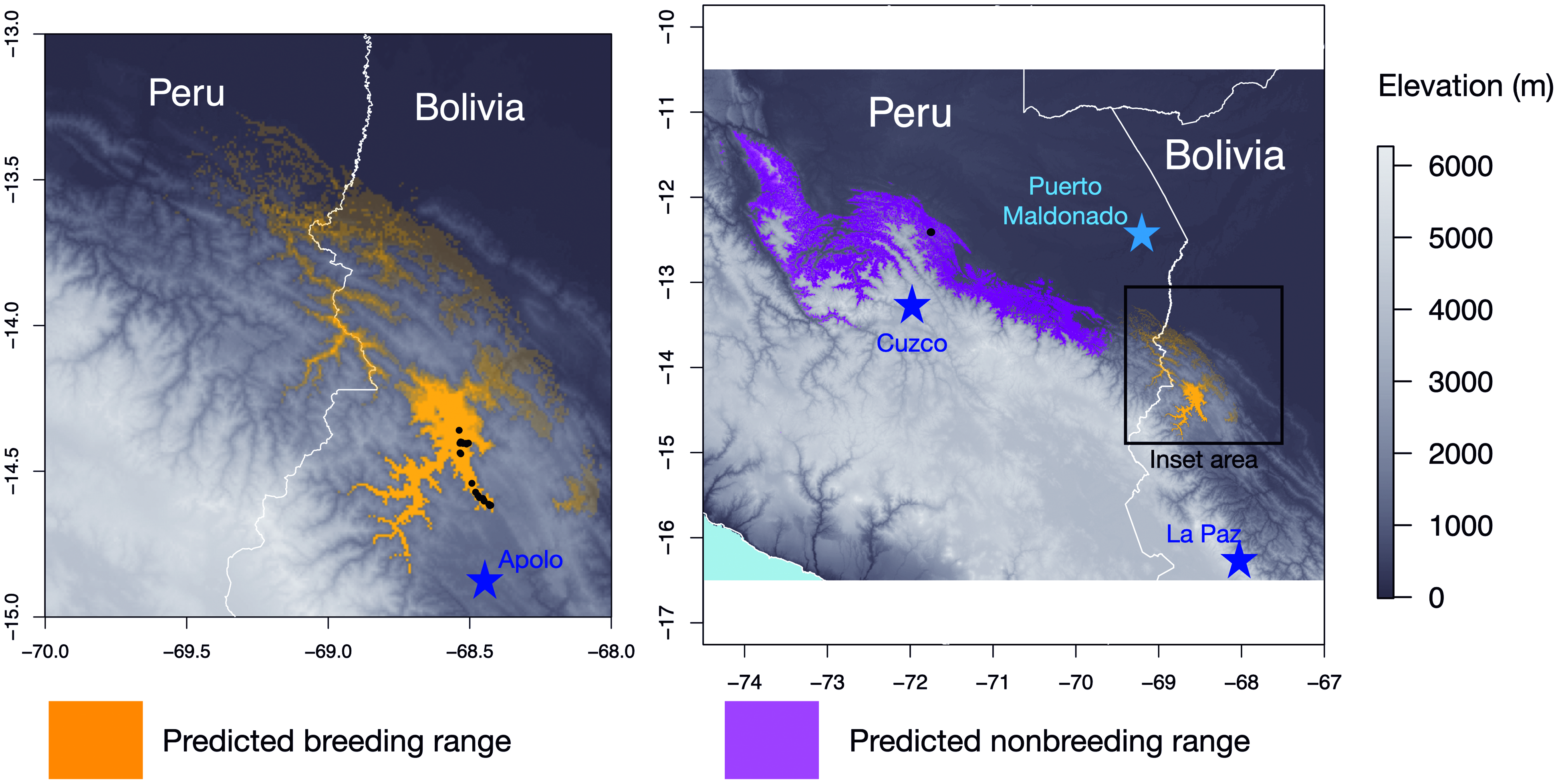

Distribution and habitat. As of this writing, documented reports of H. oneilli have only been made along the Kosñipata road, Cusco department, Peru, and the Machariapo Valley to the northwest of Apolo, La Paz department, Bolivia ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ). In La Paz, the species appears to favor short (4 m canopy) to moderatestature (~ 20 m canopy) deciduous and semi-deciduous woodland between approximately 750–1500 m elevation. Most individuals were present on ridges where the vegetation was shorter and drier. The canopy of these woodlands was dominated by Anadenanthera colubrina , Schinopsis brasiliensis ( Parker and Bailey 1991), and a tall columnar cactus, probably Cereus stenogonus (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/38163969; https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/38163964), as well as the shorter and more slender Cereus yungasensis (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/20039659; https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/38164825); ground cover was not particularly thick, but it included a spiny terrestrial bromeliad and in places a carpet of smallstature bamboo-like grass species, Pharus lappulaceus (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/31035377). Densities of Heliothraupis in this habitat were remarkably high, and in December 2012, we detected a minimum of 12 singing males along ~ 2 km (linear distance) of deciduous ridgeline habitat at about 700–900 m elevation. Some individuals were encountered on the floor of the adjacent valley (50–100 m below the tops of the ridges) where the canopy was taller and the diversity of vegetation was greater and with a denser understory, but, at least in some cases, it is likely that the birds that descended to the valley floor from more typical ridge habitat did so in response to voice playback. In mid-December 2013, RST revisited territories where we had collected males in 2012. In each instance, the territory was occupied by a new male, which further indicates the high breeding density of this species in the Machariapo valley. At higher elevations (> 1,000 m), where the edaphic conditions appeared drier, the species was present in shorter-stature (4–7 m canopy) woodland, including disturbed roadside growth, with a much denser understory with some isolated taller trees (reaching 10 m). An unidentified bamboo species (https://www.inaturalist. org/observations/20039775) formed dense patches in this woodland, and we noticed singing male Heliothraupis over these patches. In 2012, there was a seeding event with the low-stature bamboo-like Pharus lappulaceus in the valley, illustrated by the presence of Sporophila schistacea (Slate-colored Seedeater), a nomadic bamboo specialist that breeds during such seeding events ( Parker 1982, Neudorf and Blanchfield 1994). In 2019, most territories of Heliothraupis were concentrated where there was significant growth of either this or another low-stature bamboolike grass, tentatively identified as Lasiacis maculata (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/20029720). Aspecies of Guadua bamboo (https://www.inaturalist. org/observations/38163982) was present in the highestelevation territory of Heliothraupis , at ~ 1,500 m. We infer that the species may require these bamboos or bamboolike grasses as an important feature in its breeding habitat in these semi-deciduous forests. More thorough characterizations of the edaphic conditions and flora of the region can be found in Parker and Bailey (1991), Perry et al. (1997), Kessler and Helme (1999), and Cayola et al. (2005).

Observations along the Kosñipata road, Peru, have been between about 1,000 and 1,400 m elevation, at the change from “lower montane rainforest” to “cloud forest” elevation bands and the vegetation contains elements of both ( Terborgh 1985). The immediate area in which Heliothraupis has been seen is largely what appears to be second-growth (post-landslide?) humid forest with a broken canopy and high Guadua bamboo component. In 2000, the Guadua bamboo was seeding over much of the area in which we made our first Heliothraupis observation, and again, Sporophila schistacea was present. This Guadua bamboo was dying back and being replaced by vines and other second growth by 2003, only returning to become a major component of the habitat locally by about 2011 or so (DFL, personal observation).

We know of sightings of H. oneilli in the Kosñipata valley from 9 June, 30 July, 9 August, 3 September, 7 and 10 October, dates that span the heart of the dry season locally (Pepe Rojas, Julian Heavyside, personal communication). Several visits by DFL to this locality in early November to searchfor H. oneilli (including in 2003, only twoweeks after an encounter) were fruitless. Thus, the scanty evidence so far suggests that the species is only present along the Kosñipata road as a low-density non-breeder during the dry season and migrates elsewhere to breed. Observations from the Machariapo valley, Bolivia, span from 9 October 2018 (Rich Hoyer, personal communication), 19–22 November 2017 (Herman van Oosten, personal communication, 24 January 2018), 20 November (Diego Calderon, personal communication), to the latest sighting in the area (and coincidentally, the first verified observation of the species, although unidentified at the time!) on 13 March 1993 (Mark Pearman, personal communication, 2 May 2019). In both 2012 and 2013, we observed males taking up residence on territories where either no singing male had been detected for several days, or where the previous male had been collected in mid to late December, indicating either recent arrival from nonbreeding grounds or an indicator of a high instance of “floater” males looking for vacancies to fill.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |