Atherurus africanus, Gray, 1842

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6612213 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6612184 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03A91B1C-C153-4A63-C97C-F52D9CB06976 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Atherurus africanus |

| status |

|

African Brush-tailed Porcupine

Atherurus africanus View in CoL

French: Athérure africain / German: Afrikanischer Quastenstachler / Spanish: Puercoespin africano de cola de cepillo

Taxonomy. Atherurus africanus Gray, 1842 View in CoL ,

“West Africa, Sierra Leone.”

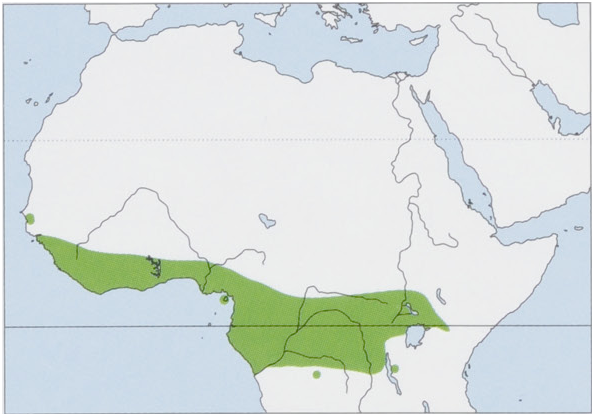

Distribution of A. africanus largely overlaps the West and Central African distribution of Hystrix cristata , and it might overlap somewhat with the distribution of H. africaeaustralis in Kenya and Uganda. Monotypic.

Distribution. W & C Africa, in the Rainforest Biotic Zone and rainforest-savanna mosaic from Guinea to E & S DR Congo and Rwanda and S to the Republic of the Congo and NW & N Angola (Cabinda and Carumbo Lagoon in Lunda Norte Province), also on Bioko I (Equatorial Guinea), and small populations in W Gambia, S South Sudan, Uganda, and E Kenya; also recorded in E Tanzania (Lake Tanganyika). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 365-600 mm, tail 100-260 mm, ear 38-39 mm, hindfoot 71-73 mm; weight 1-5—4-3 kg. The African Brush-tailed Porcupine is large and dark, with relatively long body and short, stout limbs; it appears almost entirely spiny. Dorsal pelage is dark brown and thickly spined. Hairs are modified into coarse, thick spines that are colored off-white at bases and gradually darken along shafts toward middles, appearing blackish brown at sharply pointed tips; fine hairs grow between spines. Softer spines occur on underside,legs, and head. Lengths of spines are variable and depend on body region; they are shortest (c.20 mm) on neck, longer (25-45 mm) on flanks and mid-dorsal region, and up to 90 mm on rump. Head of the African Brush-tailed Porcupine is sparsely covered with short, dark, coarse hairs, and ears are darkly pigmented and mostly naked. Mystacial vibrissae are long and black. Relative to species of Hystrix , skull of the African Brush-tailed Porcupine is elongated, with noninflated nasal bones that end anteriorly to zygomatic arch. Postorbital processes are either lacking or very weak. Incisors are smooth and without grooves on outer surfaces. Ventral pelage is off-white to pale brown. Ventral hairs are softer and less spiny than dorsal hairs and are ¢.10-15 mm. Forefeet and hindfeet are covered with coarse dark brown hairs. Each foot has five digits, and feet are partially webbed and armed with blunt claws, except on first digit of forefoot. The African Brush-tailed Porcupine has a short tail; ratios of tail to head-body length are ¢.25-50%. Tail is thick, swollen at base, tapers toward tip, and covered with short, black spines. Tail ends with a brush-like cluster of off-white or yellow, “platelet-bristles.” Each is a hollow, flattened bristle with 4-5 bead-like “platelets” or shafts that swell like rice grains at regular intervals. When shaken, they produce a rattling sound. Tail breaks easily and is often lost. Female African Brush-tailed Porcupines have two pair of lateral, thoracic mammae.

Habitat. Evergreen and gallery forests with hollow trees, buttress roots, and soft soil, especially close to streams in small valleys from sea level to elevations of ¢.3000 m. The African Brush-tailed Porcupine also occurs on farmlands adjacentto forest.

Food and Feeding. The African Brush-tailed Porcupine is primarily frugivorous and eats fruits from forest trees, most of which have fallen to the ground from the tree canopy. It also eats flowers, leaves, and some roots. When adjacent to farms,it will eat maize, manioc (cassava), bananas, and palm nuts. Occasionally, it eats carrion and earthworms.

Breeding. Young African Brush-tailed Porcupines are found during most months of the year in the DR Congo, and this pattern likely occurs throughout the Rainforest Biotic Zone. In the wild, females have 2-3 litters/year. Gestation lasts 100-120 days, followed by birth oflitters of 1-2 young (occasionally up to four). Female African Brushtailed Porcupines are likely polyovular, so the common litter size of one observed in captivity may be an artifact of holding conditions. Females have a bicornuate uterus, with two separated uterine horns, a uterine body, and a cervix. Females in captivity show spontaneous estrous cycles in a polyestrous pattern, with an average estrous cycle of 27-1 days. Young are born weighing ¢.100-175 g and are precocious; their eyes are open, and they have soft spine-like hairs on their back and flanks and can walk on all four legs within a few hours of birth. Young nurse for about two months although they begin to eat solid food at 2-3 weeks of age. The African Brush-tailed Porcupine grows slowly; adult size is reached after ¢.300 days, and sexual maturity at about two years of age or older.

Activity patterns. The African Brush-tailed Porcupine is a strictly nocturnal and primarily terrestrial. It hides during the day in dens located in hollow trees, hollow logs, caves, or underbrush piles or roots of large trees (it does not dig its own burrow). It defecates regularly at the same place, either under a rock or in a den. It walks and trots along the forest floor, swims readily, and can climb trees to a limited extent to escape pursuit threat. While moving, it carriesits tail held slightly upward and back from its body; sometimes rustling of rattle-quills can be heard even when it cannot be seen. African Brush-tailed Porcupines in the wild in Gabon typically left their hiding places at ¢.17:00 h, returning to their dens at c¢.05:30 h. Nightly activity, particularly among females, usually followed a trimodal pattern with two rest periods during the night, although the pattern shifted to bimodal on moonlit nights. Female rest periods clustered around 20:00-21:00 h and again at 02:00-04:00 h. Males spent more time immobile and had more irregular patterns, resting in the middle of the night. Individuals also took rest periods of about ten minutes every hour; these rests tended to be longer in the middle of the night than at the start or end, and longer in the presence of bright moonlight. On dark nights, females did not normally take a rest in the middle of night, although males rested some of the time. Average inactive time on dark nights was 1-9 hours. On nights close to full moonlight, period of inactivity increased to an average of 3-4 hours. When alarmed or threatened, an African Brush-tailed Porcupine will raise spines on its back and shakeits tail, rustling the bristles. If, after this warning display,it remains threatened, it will move quickly sideways and backward with its sharp, pointed quills facing forward toward the opponent.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. While foraging at night, African Brush-tailed Porcupines move rapidly across the landscape, traveling ¢.100 m every four minutes. They follow well-established trail networks as they move through undergrowth and generally travel alone. Average nightly distances moved varied with sex and moon phase. Males averaged 1697 m/night with moonlight and 2333 m on dark nights, and females averaged 1646 m/night with moonlight and 1953 m on dark nights. Home ranges of males in Gabon averaged slightly larger than those of females, with means of 15-6 ha and 10-2 ha, respectively. Male and female home ranges overlap. Although total area used and distance traveled did not differ significantly between males and females, pattern of space use did. Male African Brush-tailed Porcupines made single, complete circuits of their home ranges and typically rested in the middle of the night at the end of the home range opposite the sleeping den and did not display territorial behavior. Females followed no regularitinerary while active, wandering back and forth unpredictably. Although African Brush-tailed Porcupines travel alone at night in search of food, they are thought to be gregarious. They occasionally meet at feeding places and have a tendency to share dens during the day. Of 22 dens investigated in Gabon, twelve contained one individual, seven each held two individuals, one held three individuals, and one held four individuals. Associations in the dens were all male, all female, or males and females. During the period of the study, males used an average of eight dens, and females used six dens. Some dens were used repeatedly by the same individual, but others were used only once. In captivity, African Brush-tailed Porcupines exhibit mutual grooming along with auditory displays of dominance and submission. They may form family groups of one male, one female, and offspring, although social organization appears fluid, without formation of monogamous pairs or cohesive groups. Breeding system is currently unknown. Populations of African Brush-tailed Porcupines can be locally abundant, with densities of 2:4-13-2 ind/km? in the Central African Republic, 55 ind/km? in Equatorial Guinea, and 58 ind/km? in Gabon. In Gabon, sex ratio was male biased at 2-4:1 for adults and 2-1:1 for subadults, although this bias may have been an artifact of differences in capture probabilities between sexes.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Main predators of the African Brush-tailed Porcupine are humans and Leopards (Panthera pardus). It is vigorously hunted by humansfor its succulent flesh and is one of the most common bushmeat species in markets across West and Central Africa. It does not appear to be overhunted, although its relatively low recruitment rate, due to fairly long generation times, seems to contradict that conclusion. Loss of forest habitat is a cause for concern in parts ofits distribution. It is also killed as a crop pest.

Bibliography. Albrechtsen et al. (2005), Anadu et al. (1988), Carr et al. (2013), Colell et al. (1994), Cordeiro (1998), Emmons (1983), Fa et al. (2002), Fischer et al. (2002), Foley et al. (2014), Happold (2013a), Hoffmann & Cox (2008), Huntley & Francisco (2015), Mayor et al. (2003), Nowak (1999a), Storch (1990).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.