Cyrtodesmus baerti, Shear & Peck, 2018

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4388.3.7 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:75F1D1A3-385F-40DD-B4E8-91ABD5BD7FFD |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5961729 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B1CB4B-FFA5-703A-8DEA-A006FD4D258E |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Cyrtodesmus baerti |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Cyrtodesmus baerti , new species

Figs. 1–11 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURES 2, 3 View FIGURES 4, 5 View FIGURES 6–9 View FIGURES 10, 11

Types: Male holotype, 2 female and 3 juvenile paratypes from 4 km east of Santa Rosa , Isla Santa Cruz, Galápagos , Ecuador, in pit traps set along the roadside in an agricultural zone under introduced Cedrella odorata trees, 10 April–4 May 1996, S. Peck ( Sta. 12, #96–165). All specimens deposited in the collections of the California Academy of Science, San Francisco , California, USA. The type material includes SEM stubs WS29-9 and WS29- 10.

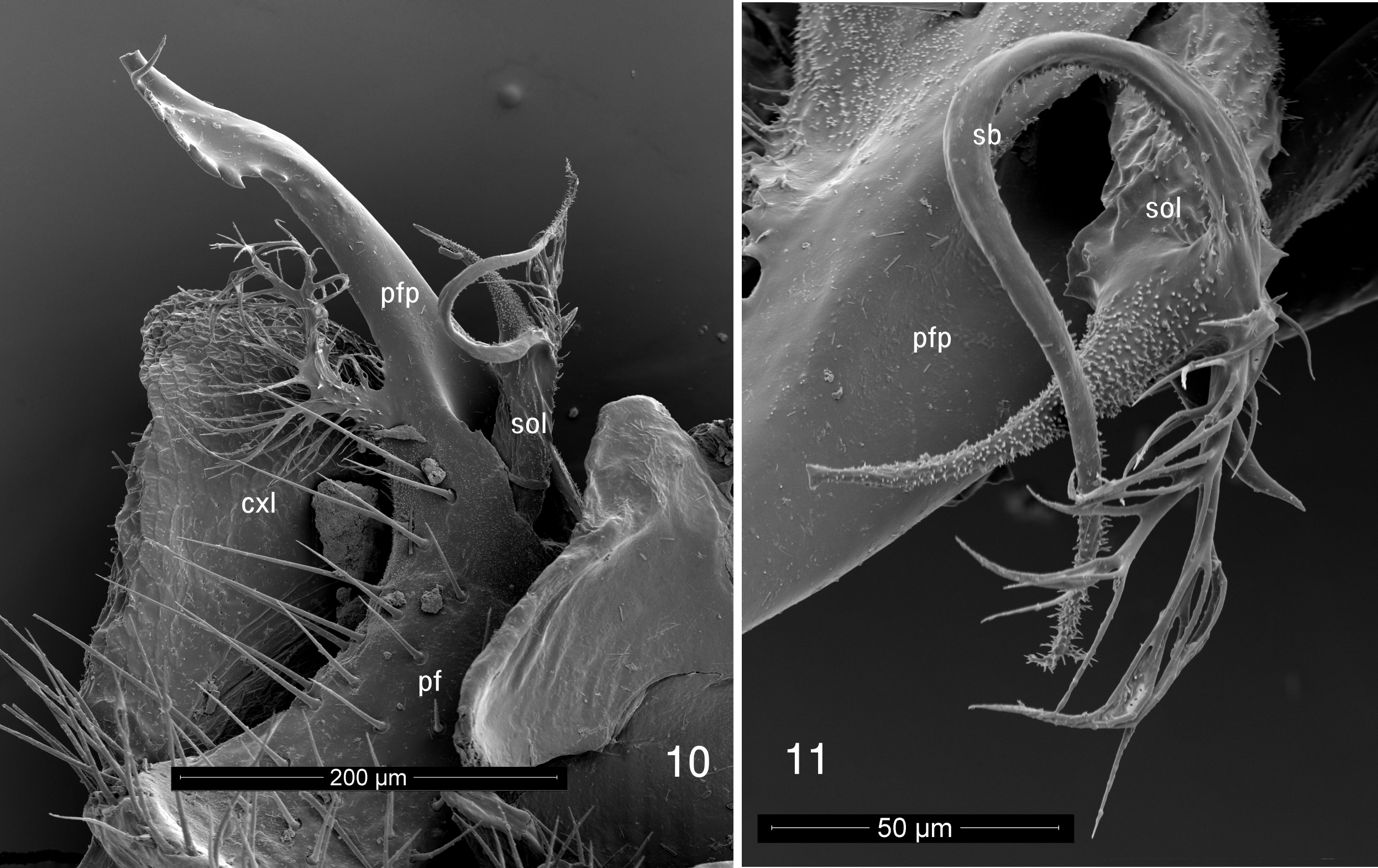

Diagnosis: A small ( 7 mm body length) species of Cyrtodesmus distinct from other species in having the metatergal tubercles of graded size and densely and randomly distributed ( Fig. 8 View FIGURES 6–9 ) and in the quadripartite solenite and toothed prefemoral process of the gonopod ( Figs 10, 11 View FIGURES 10, 11 ).

Etymology: Named to honor the contributions to our knowledge of Galápagos arthropod biodiversity by Léon Baert, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium.

Description of male: Body length approximately 7 mm, metazonite diameter 1.3 mm. Twenty segments (18 podous segments + 1 apodous segment + telson). Color dark blackish brown. Head ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 2, 3 ) without sculpture. Antennae sharply geniculate, fifth antennomere the largest (order of length 5>3>4>2>1>6>7>8). Collum ( col, Fig. 2 View FIGURES 2, 3 ) with frontal row of eight prominent tubercles, posteriorly with densely set smaller tubercles, lateral edges of collum overlapped by enlarged lateral lobes of first pedigerous segment ( sl, Figs 2, 3 View FIGURES 2, 3 ). First pedigerous segment ( 1, Fig. 3 View FIGURES 2, 3 ) ornamented as collum, but with two large, semicircular lateral lobes projecting forward, partially concealing sides of head and antennae; lobes divided into large anterior region and smaller, laterally projecting posterior region, posterior region with distinct notch ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Metazonites of subsequent segments densely tuberculate ( Figs 3 View FIGURES 2, 3 , 4 View FIGURES 4, 5 , 9 View FIGURES 6–9 ), each tubercle with 3–5 setae at apex, tubercles with long, unsocketed cuticular filaments on sides and on cuticle between tubercles. Surfaces of metazonites covered with secretion mixed with dark soil particles. Metazonites with limbus consisting of blunt, squared, well-spaced teeth dorsally, teeth gradually becoming longer and more acute ventrally ( t, Fig. 5 View FIGURES 4, 5 ). Prozonites with three zones of sculpture ( a, m, p, Fig. 3 View FIGURES 2, 3 ; see notes below), the posteriormost zone smooth. Paranota strongly deflexed, vertical, without lobes but each with pronounced posterior notch near base ( pn, Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4, 5 ). Ozopores not detected. Terminal segment not concealed, bearing on its ventral side four spinnerets ( sp, Fig. 7 View FIGURES 6–9 ) in roughly square arrangement on three-lobed prominence; each spinneret in its own rounded recess.

Gonopod ( Figs. 10, 11 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) typical of genus, coxa with flattened lateral lobe ( cxl, Fig. 10 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) partially concealing telopodite in lateral view. Prefemoral region ( pf, Fig. 11 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) strongly concave, setose; prefemoral process ( pfp, Figs. 10, 11 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) long, slightly curved, apically with six recurved teeth and small filamentous process, basally with complex, fimbriate branch. Solenite ( sol, Fig. 10 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) basally surrounded by prefemoral process, four-branched, one branch fimbriate, second short, curved-conical, smooth. Third branch ( sb, Fig. 11 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) longest, strongly curved, carrying seminal groove, with few small teeth along length, these becoming more numerous near tip, expanding into short, branched fimbriae. Fourth branch stout, long, tapering, set with many minute teeth, apically expanded.

Female similar to male in all nonsexual details.

Notes: Cyrtodesmus baerti differs in the details of its gonopods from other Cyrtodesmus species, so far as can be determined. Loomis (1964) illustrated the gonopods of the species he described from a variety of angles, making the details hard to match up. However, the toothed prefemoral process ( pfp, Fig. 11 View FIGURES 10, 11 ) in combination with the long, sinuous seminiferous process ( sp, Fig. 12) arising from the solenite are distinct from all species for which males are known. Cyrtodesmus dentatus Loomis, 1964 has small teeth on the prefemoral process but in a different position, while C. lyripes Loomis, 1964 may have additional solenite processes, but this is difficult to ascertain from the drawing.

Volvation, or the ability to roll up, is a defensive mechanism that has been developed independently in several evolutionary lines in the Polydesmida ( Golovatch 2003, Shear 2015).

In Cyrtodesmus View in CoL ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ), the collum is reduced and the first pedigerous segment is greatly enlarged. The terminal segment or epiproct is cup-shaped and can be pressed tightly against the prozonite of the second pedigerous segment. The vertically oriented paranota ( pn, Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4, 5 ) are deeply notched at their bases, and the front edge of each paranotum tucks neatly under the rear edge of the preceding one, locked in place by securely inserting into the basal notch. The hypertrophied first segment bears large, semicircular lobes on either side which serve, along with the paranota, to protect the head, antennae and short legs. This lobe is divided by cuticular sculpture into two parts, an anterior section which tucks under the paranota of succeeding segments, and a posterior lateral portion probably homologous to the paranota, judging from the notch at the base and the overlap with the next posterior segment. The final result is a flattened spheroid or bulky, rounded disk. It seems that volvation and acquired camouflage using soil particles are the only defenses of C. baerti , since ozopores cannot be detected, even under scanning electron microscopy. Loomis (1964) wrote that the “…conspicuousness of the pores and pore tubercles are subject to great variation and constitute specific characters….( Loomis 1964, p. 34).” In some of the species he subsequently describes, pores are not mentioned, are scarcely detectable, or, as in the type species C. velutinus Gervais, 1847 View in CoL , on tubercles opening at a translucent tip.

Many animals of the leaf litter and soil have special adaptations of the cuticle that collect and cause particles of soil to adhere. In the case of Cyrtodesmus View in CoL species, it would appear that the main mechanism is through a secretion, which makes it difficult to clean the particles off, even under sonication. The surface of the metazonite cuticle of all species of Cyrtodesmus View in CoL is tuberculate and strongly setose ( Figs 4 View FIGURES 4, 5 , 8, 9 View FIGURES 6–9 ). In C. baerti , unlike many species in which the tubercles are clearly of two different size classes, the tubercles are graded in size and densely and randomly distributed, although the largest of them ( Mt, Fig. 8 View FIGURES 6–9 ) may appear to form three rough transverse rows when the metazonites are viewed laterally. In other Cyrtodesmus View in CoL , the major tubercles are more regularly arranged and tend to form what appear to be longitudinal crests running down the length of the animal. When Loomis (1964) illustrated the tubercles, he showed them with just a single seta each, but the tubercles of C. baerti have three to five setae springing from the apex of each tubercle. Where the tubercles have been broken or damaged by handling, it can be seen that their walls are relatively thin and that they have a cavity inside. We hypothesize that the tubercles contain glands that produce a sticky secretion, which emerges from the sockets around the bases of the setae, just as does the “silk” from polydesmidan epiproct spinnerets ( Shear 2008; this can also be seen in our Fig. 8 View FIGURES 6–9 ). The secretion then “climbs” the setae and collects in blobs distally ( g, Fig. 9 View FIGURES 6–9 ), just as has been shown for several chordeumatidan millipedes ( Shear 2015). In addition to the tubercles, SEM reveals that the intervening cuticle is densely set with fine, unsocketed cuticular spines which probably help to catch and hold particles. The posterior margins of the metazonites show a limbus which consists of regularly spaced, flat teeth. Dorsally these teeth are truncate, almost square, but ventrally they are much larger and acute ( t, Fig. 5 View FIGURES 4, 5 ). The function of the limbus is obscure; it may in some way facilitate the telescoping of prozonites into the next anterior metazonite, or perhaps prevent foreign matter from getting stuck between the segments. As with most volvating polydesmidans, the cuticle is thick and hard.

The prozonites are unusual in having three zones of sculpture, anterior, median and posterior ( a, m, p respectively, Fig. 3 View FIGURES 2, 3 ). The anterior portion ( a, Fig. 6 View FIGURES 6–9 ) has closely spaced, small, acute tubercles with prominent ridges; from a directly dorsal view these resemble a swarm of amoebae. The tubercles grow larger and more elongate posteriorly, ending in a row which resembles a second limbus. In the median zone ( m, Fig. 6 View FIGURES 6–9 ), similar tubercles are smaller and more closely spaced, while some of them appear grouped together to form multitubercle mounds that are open at the tip. The median zone ends in an irregular margin behind which the posterior zone consists of perfectly smooth cuticle, with a shallow groove separating it from the distinctive sculpture of the metazonite ( met, Fig. 6 View FIGURES 6–9 ).

The spinnerets of cyrtodesmids ( Fig. 7 View FIGURES 6–9 ) have not been illustrated previously. The trilobed process which bears them is not seen in other polydesmidans ( Shear 2008) and may be diagnostic for Cyrtodesmidae .

Interpretations of the gonopods by Loomis (1964) require supplementation. Loomis referred to the fimbriate branch of the prefemoral process as “seminiferous” but this is not the case. The solenite is a separate branch of the telopodite which evidently does not appear in several of Loomis’ gonopod drawings, probably made at relatively low magnification with a dissecting microscope, and at different angles. Loomis may well have missed the complex processes of the solenite due to these insufficient optics; future work on cyrtodesmids should involve scanning electron microscopy to properly resolve the details. A key point, at least for C. baerti , is that the base of the solenite is enveloped by the prefemoral process.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Cyrtodesmus baerti

| Shear, William A. & Peck, Stewart B. 2018 |

C. baerti

| Shear & Peck 2018 |

C. baerti

| Shear & Peck 2018 |

C. baerti

| Shear & Peck 2018 |

Cyrtodesmus

| Gervais 1847 |

C. velutinus

| Gervais 1847 |

Cyrtodesmus

| Gervais 1847 |

Cyrtodesmus

| Gervais 1847 |

Cyrtodesmus

| Gervais 1847 |