Corasoides Butler, 1929

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.3853/j.2201-4349.69.2017.1671 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B387B7-3646-FF99-3BCA-FEB8FB44FD6E |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Corasoides Butler, 1929 |

| status |

|

Genus Corasoides Butler, 1929 View in CoL View at ENA

Corasoides Butler, 1929: 42 View in CoL ; Neave, 1939: 833; Roewer, 1954: 61; Bonnet, 1956: 1925; Lehtinen, 1967: 225; Forster & Wilton, 1973: 128; Gray, 1981: 797; Main, 1982: 92; Brignoli, 1983: 467, 533; Davies, 1988: 70; Platnick, 1993: 541; Platnick, 1997: 609; Wheeler et al., 2016: 12, 27, 34, 35.

Type species. Corasoides australis Butler, 1929 View in CoL , by monotypy.

The first inference to a spider of this genus appears to be Rainbow’s (1897) description of a web identified by him as belonging to Agelena labyrinthica, Clerck, 1757 View in CoL (a European species). From his description, and from the locality given (Sydney, Guildford and Fairfield), it seems that he was referring to what we now call C. australis View in CoL .

Rainbow’s account was noted by Butler (1929) who questioned Rainbow’s identification and the presence in New South Wales of A. labyrinthica View in CoL . Butler proceeded to describe the monotypic genus Corasoides View in CoL and its undescribed type species, Corasoides australis View in CoL . The only review of Corasoides View in CoL since that time has been that of Lehtinen (1967) in which he included a New Zealand species, Rubrius mandibularis Bryant, 1935 (later transferred to Mamoea View in CoL ).

Family affiliations

Butler placed Corasoides View in CoL in Agelenidae View in CoL : Ageleninae, probably in part because of its platform web structure and its strong superficial resemblance to Agelena labyrinthica View in CoL .

Corasoides View in CoL remained in Agelenidae View in CoL ( Roewer, 1954; Bonnet, 1956) until Lehtinen (1967) transferred it to the Amaurobiidae View in CoL : Desinae. Lehtinen removed Corasoides View in CoL from Agelenidae View in CoL on account of the unpaired colulus, which is unpaired in all Amaurobiidae, sensu Lehtinen View in CoL (with one unusual exception) but paired in Agelenidae View in CoL . The main attribute of Lehtinen’s Amaurobiidae View in CoL was the presence of a median apophysis in the male palp. Lehtinen acknowledged the absence of the median apophysis in Corasoides View in CoL (and similarly so in Stiphidion View in CoL and Porteria View in CoL which he also placed in Desinae) but he regarded this as a secondary loss. Lehtinen saw a division of his Amaurobiidae View in CoL into two depending upon the presence or absence of a secondary conductor. Classical characters based on spination, trichobothria, maxillae, eyes etc., he regarded as inconsequential and often associated with overall size ( Lehtinen, 1978). Those subfamilies lacking a secondary conductor included Desinae, Matachiinae and Stiphidiinae .

Forster & Wilton (1973) raised the subfamily Stiphidiinae Dalmas, 1917 to family status within the Amaurobioidea . They placed the New Zealand Cambridgea View in CoL , Nanocambridgea View in CoL and Ischalea View in CoL in Stiphidiidae View in CoL as well as the Australian Baiami View in CoL , Procambridgea View in CoL and Corasoides View in CoL . Morphologically, Forster & Wilton (1973) restricted the Amaurobiidae View in CoL to those taxa with a well-developed and strongly sclerotized median apophysis while Stiphidiidae View in CoL they defined as possessing a simple median apophysis that showed a strong tendency to reduction and eventual loss as in Corasoides View in CoL .

Stiphidiidae View in CoL remained in the Amaurobioidea on account of the presence of the median apophysis (or its assumed secondary loss) and the weakly developed and unbranched tracheal system that is confined mainly to the abdomen (Forster & Wilton, 1973).

The position of Corasoides View in CoL in Lehtinen’s Amaurobiidae View in CoL , Desinae, is dependent upon the absence, as a secondary loss, of both the median apophysis and the secondary conductor in Corasoides View in CoL . Members of Lehtinen’s Desinae show a trend towards reduction or loss of the median apophysis.

Griswold et al. (1999) showed that Amaurobiidae (sensu Lehtinen, 1967) View in CoL is polyphyletic and several of his subfamilies, including Desinae, did not belong in the Amaurobiidae View in CoL . This confirmed aspects of Forster & Wilton’s (1973) treatment of Lehtinen’s Amaurobiidae View in CoL , including the raising of the Desinae to family status within the Dictynoidea. While they transferred many of the genera that Lehtinen had placed in the Amaurobiidae View in CoL to their new family Desidae View in CoL , based upon the branching structure of the tracheae, they excluded Corasoides View in CoL . Corasoides View in CoL cannot be placed in Forster & Wilton’s Desidae View in CoL because of the absence of a well-developed and sclerotized median apophysis and its simple, unbranched tracheal system.

Forster & Wilton’s (1973) elevation of the Stiphidiinae to family status and the inclusion of Corasoides View in CoL remained problematic. The colulus of Stiphidiidae View in CoL is typically a large, hairy, flattened plate, suggesting recent reduction from a cribellum; the colulus of Corasoides View in CoL (and Cambridgea View in CoL ) has the form of a small, semicircular flap.

The Stiphidiidae View in CoL are not adequately separated from the Agelenidae View in CoL , especially since Forster & Wilton have included within the Agelenidae View in CoL taxa with a single, undivided colulus and with unelongated posterior spinnerets. The only attribute setting Agelenidae (sensu Forster & Wilton, 1973) View in CoL apart from other families is the absence of trichobothria on the cymbium. This attribute excludes Corasoides View in CoL from Agelenidae View in CoL .

Forster & Wilton (1973) admitted that the structure of the web was the most distinctive feature of the Stiphidiidae View in CoL . They explained how it could easily have been transformed from the flat, cone-shaped web of Stiphidium (sic, misspelling of Stiphidion View in CoL ) into the platforms of Cambridgea View in CoL , Nanocambridgea View in CoL , Procambridgea View in CoL and other genera they placed in Stiphidiidae View in CoL . However, this explanation is dependent upon the spider moving on the under surface of the web and Forster & Wilton mistakenly attributed this behaviour to Corasoides View in CoL , which moves on the upper surface of the web. There is also an presumption that this is how Stiphidion View in CoL use their web platform.

The importance of the tracheal system as a taxonomic indicator is also doubtful since it is not consistent even within the classification of Forster & Wilton. In addition, Lehtinen (1978) pointed out that Lamy’s (1902) work showed that the degree of tracheal branching could be dependent upon environmental adaptation, that is, tracheal ramification was often indicative of an active hunting life style.

This leaves no remaining argument from Forster & Wilton (1973) for including Corasoides View in CoL in their Stiphidiidae View in CoL . Gray (1981) also questioned the placement of Corasoides View in CoL within Forster & Wilton’s Stiphidiidae View in CoL .

Davies (1988) in her discussion of the family placement and relationships of Stiphidion View in CoL , suggested removal of Ischalea View in CoL (on account of the presence of lateral teeth on the epigyne and a well-developed median apophysis) and Procambridgea View in CoL (on account of its marked trochanteral notches, proximal calamistrum and unusually reduced AME) from Stiphidiidae View in CoL . She, however, retained Corasoides View in CoL within the Stiphidiidae View in CoL , along with Baiami View in CoL , Cambridgea View in CoL and Nanocambridgea View in CoL and Stiphidion View in CoL , as these share a reduced or absent median apophysis, an epigyne without lateral teeth, an extensive conductor and a spiniform embolus.

Wheeler et al. (2016), using results from phylogenetic analyses of markers from mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, transferred Corasoides View in CoL from Stiphidiidae View in CoL to Desidae View in CoL . Similarly, the Australian Baiama and the closely related Cambridgea View in CoL and Nanocambridgea View in CoL from New Zealand (all of which run on the under surface of their web) were also transferred from Stipidiidae.

Porteria View in CoL , retained in Desidae View in CoL , is well supported as the sister group to Corasodes. Lehtinen(1967) first made the Australian/South American connection, linking Corasoides View in CoL and Porteria View in CoL in his Desinae on the basis of their similar abdominal pattern (although a similar pattern can also be found in some Dolomedes View in CoL ), the absence of a median apophysis and the pattern of pyriform spigots on the anterior lateral spinnerets. Both Corasoides View in CoL and Porteria View in CoL also run on the upper surface of their web.

Wheeler’s support for Porteriinae, which contains the above mentioned five genera, was strong, although support for Desidae View in CoL itself was weak. His Desidae View in CoL is diverse, including genera both cribellate and ecribellate, with simple to complex tracheae and the spider’s running atop or below the web. Wheeler was inclined to raise the Porteriinae (and several other groupings) to family level but declined to do, so awaiting further study and the inclusion of more genera.

Diagnosis

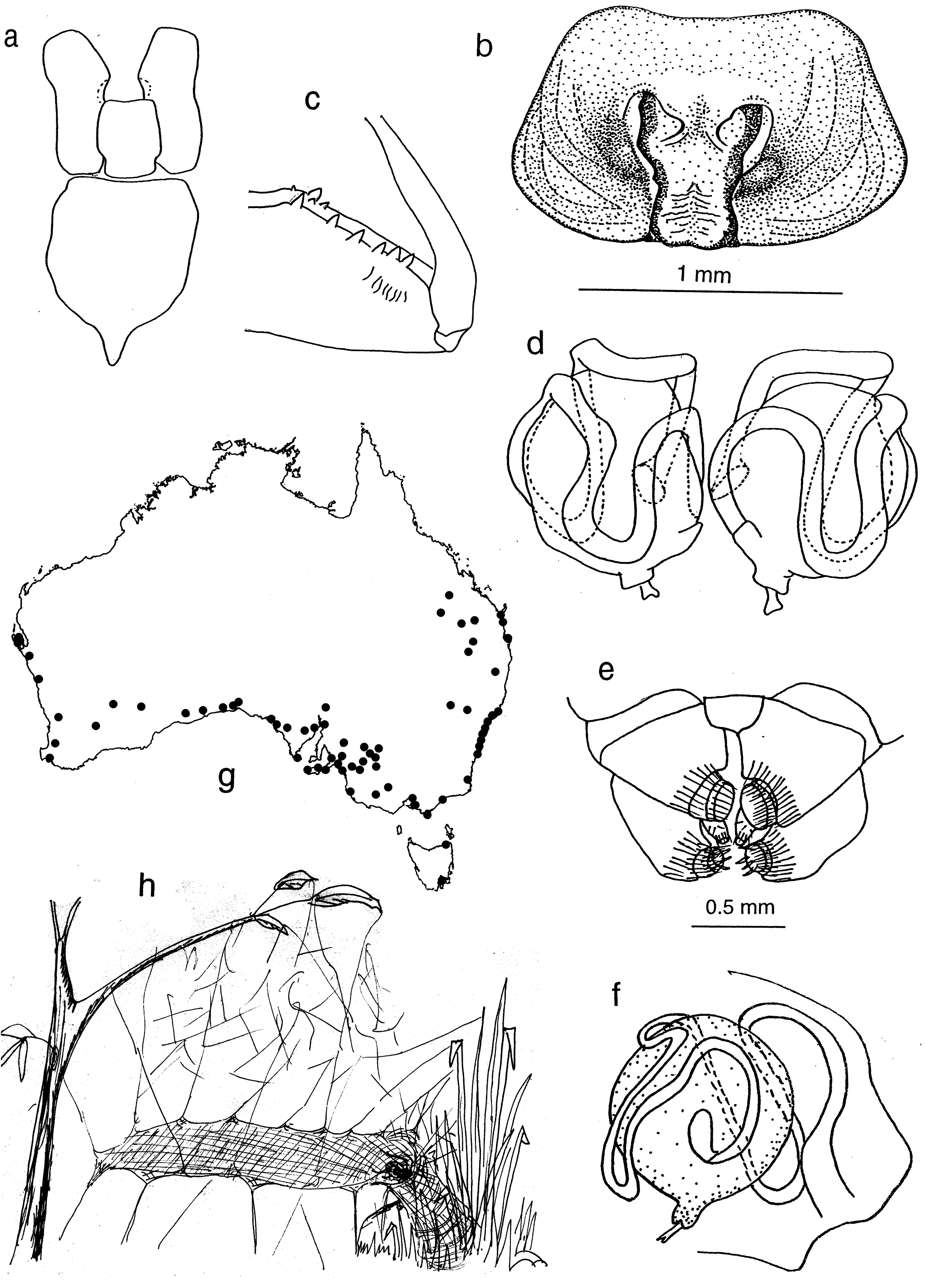

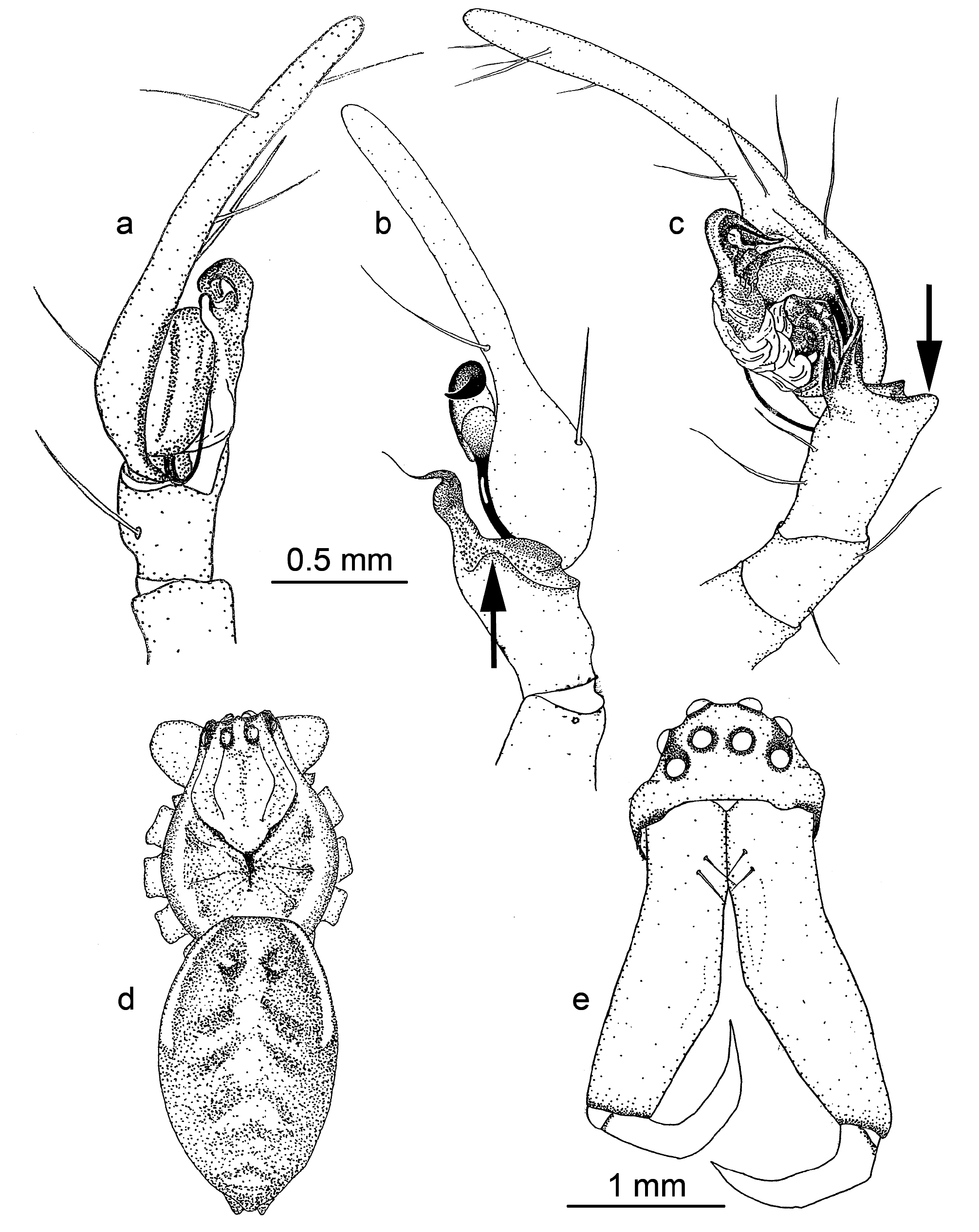

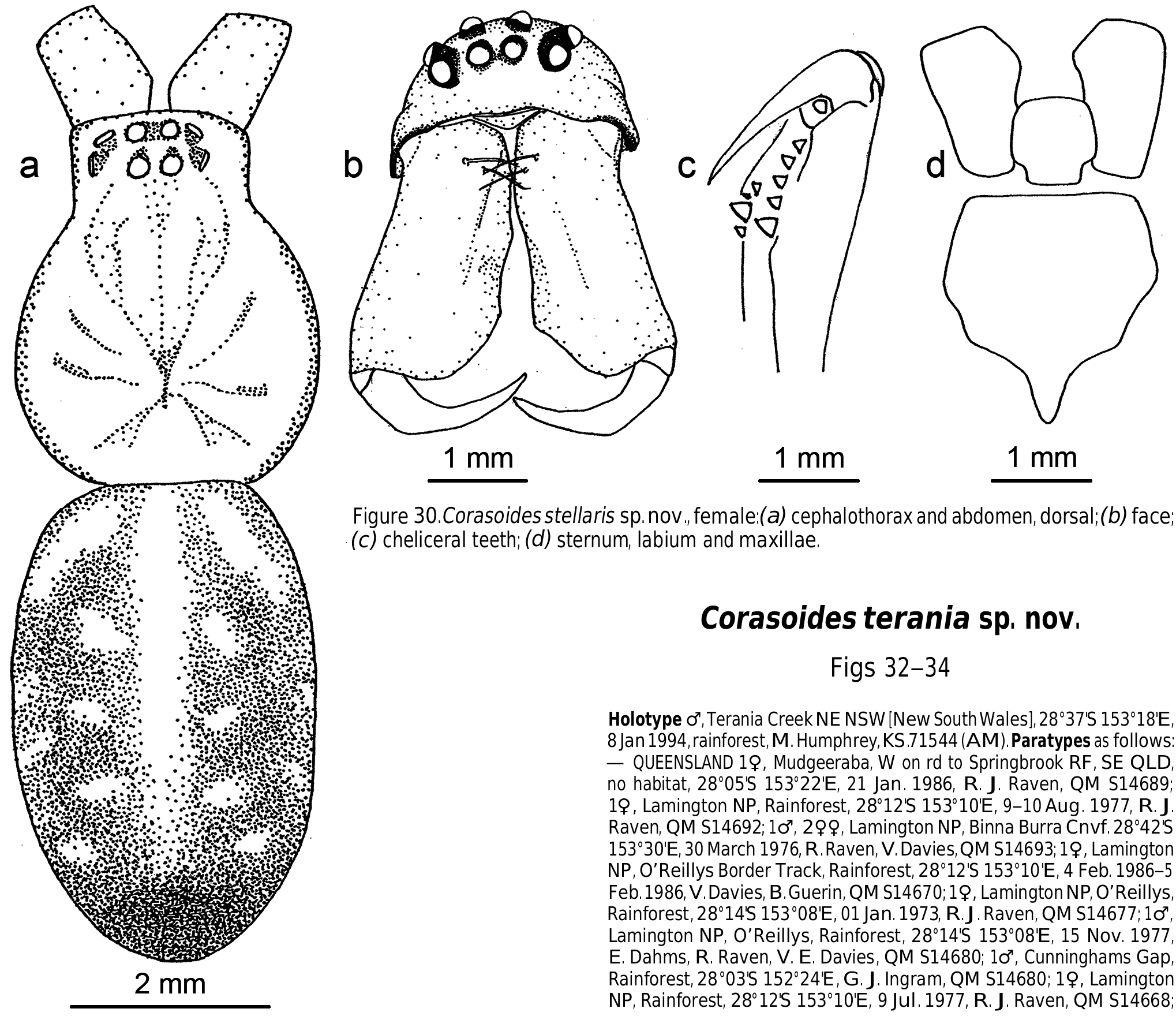

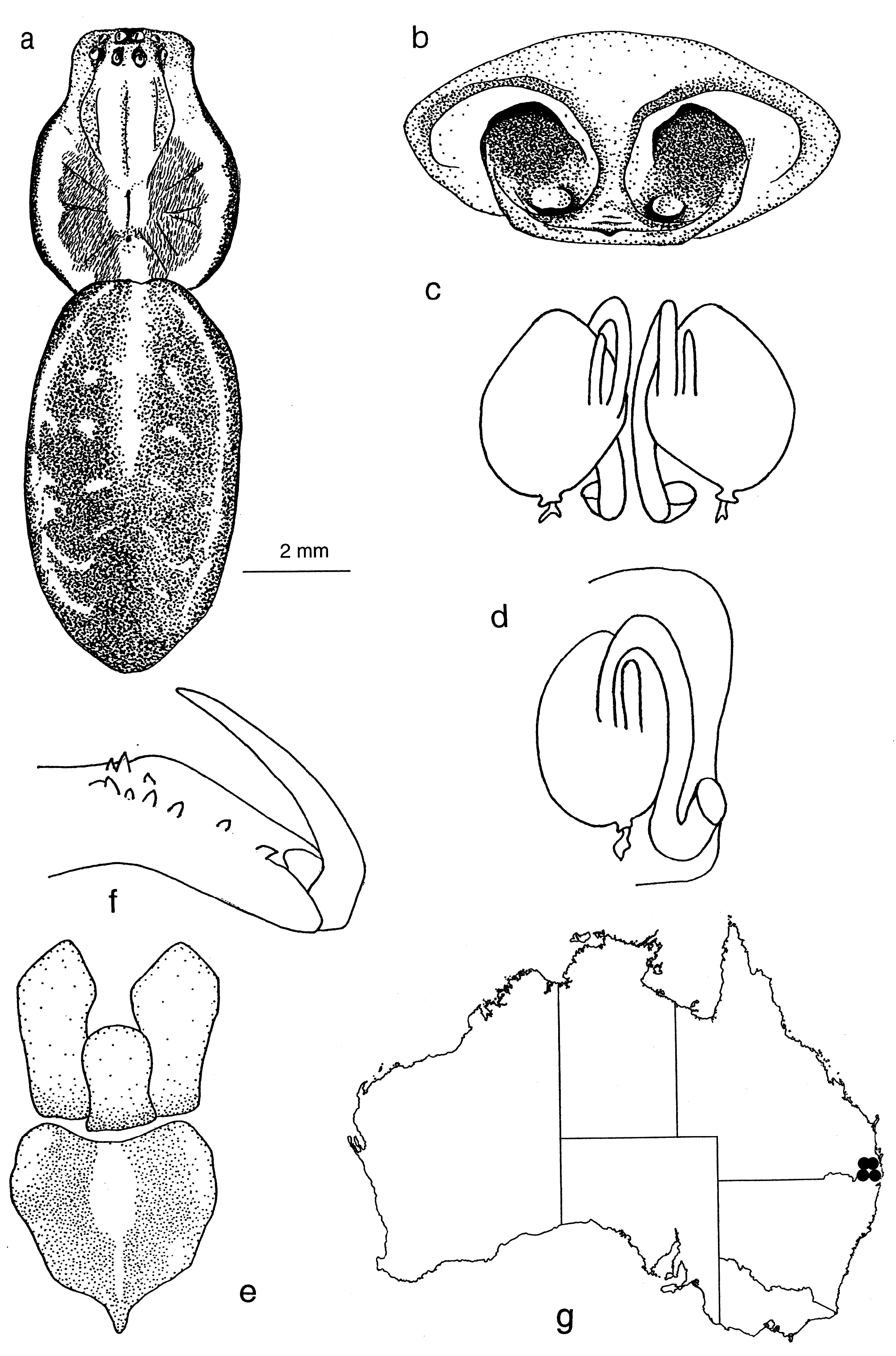

Within Wheeler’s Porteriinae, Corasoides can be distinguished behaviourally from Nanocambridgea , Cambridgea and Baiami by its web structure and mode of moving on the upper surface of the platform. Morphologically Corasoides can be separated from these genera by the distinct abdominal pattern ( Figs 2a–g View Figure 2 , 5a–c View Figure 5 , 15d View Figure 15 , 30a View Figure 30 , 33a View Figure 33 ): pseudo-feathery hairs ( Fig. 3b View Figure 3 , upper right); more retromarginal than promarginal cheliceral teeth; male palp with acutely bent and spine-like retrolateral tibial apophysis and a bristled retroventral apophysis.

Simon’s description of Porteria is inadequate and this genus is currently under study ( Merrill, 2014; unpublished thesis). Wheeler has described Corasoides as appearing as a giant version of Porteria . Until further details are available, Corasoides can be distinguished from Porteria by the presence in most species of three (sometimes two), rather than four tibial processes and the absence of notches on the trochanter.

Description

Small to large (carapace length 2.1–7.9 mm), ecribellate spiders.

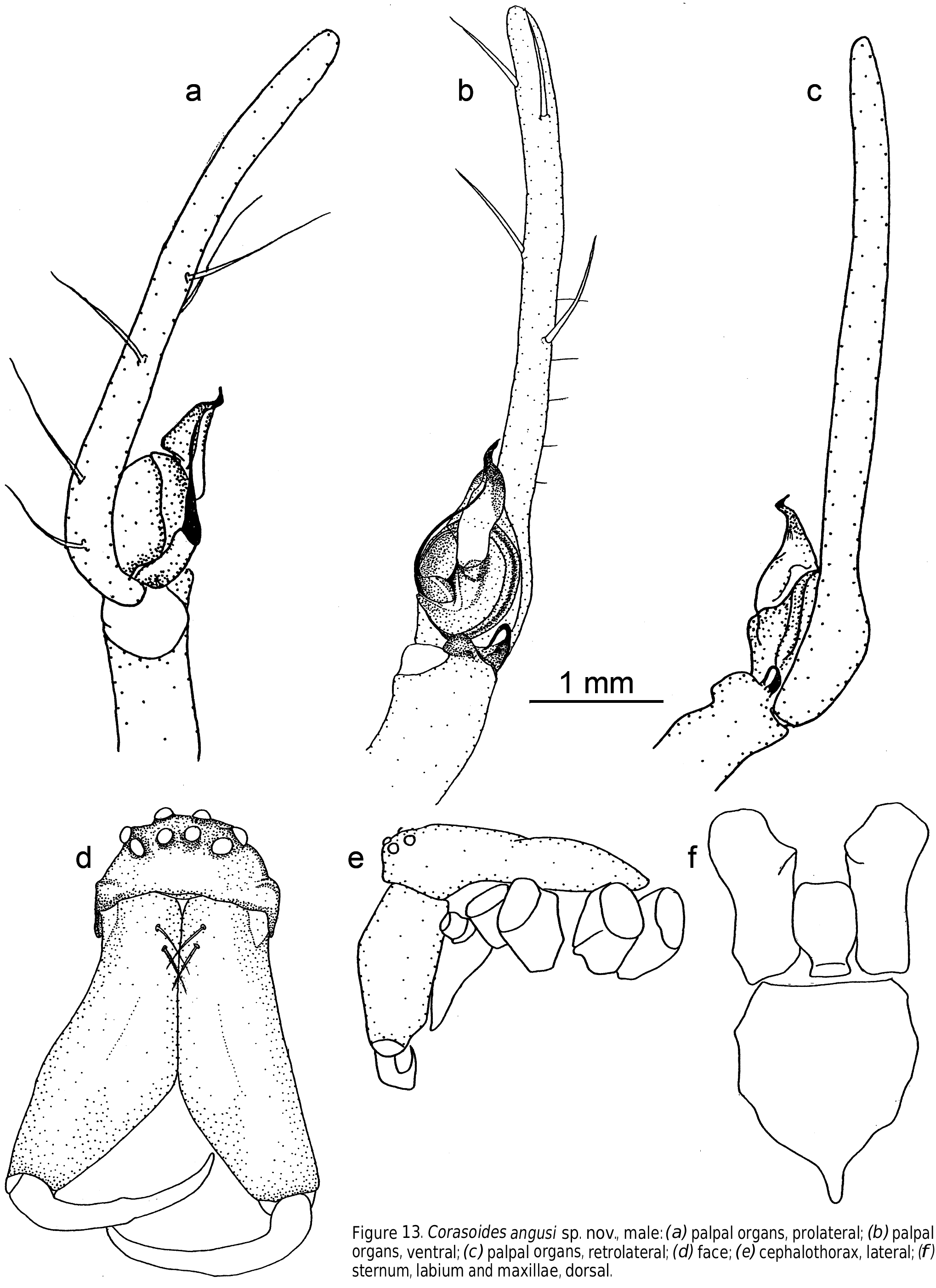

Carapace. Longer than wide with discernible head area. Fovea long. Carapace cream to reddish tan to black, darker in head and cheliceral area. Carapace with little pattern or with a pattern consisting of a cream to light tan background with a medial, light brown or tan stripe from ocular quadrangle to pedicel. This is flanked on either side by a brown or tan region extending to the posterior of the carapace but excluding the petiole region and the carapace is bounded by dark edging. Maxillae long, distally enlarged and converging. Labium basally notched. Sternum as long or longer than wide, with distinct posterior point produced between coxae IV. Clypeus broad, often concave in male.

Abdomen. Ovate. Basic pattern, dorsum: central pale stripe or medial area, white/yellow dorsolateral stripes at least to anterior third of abdomen, two rows of white/yellow spots on black background between dorsolateral stripes and central stripe and decreasing in size posteriorly and with first two pairs prominent. In some specimens, the pattern may be less distinct and in some species may be reduced to a vague double row of pale spots on the dorsal surface ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 5 View Figure 5 , 15d View Figure 15 , 30a View Figure 30 , 33a View Figure 33 ). Venter pale, laterally with black striation.

Eyes. Anterior row eyes slightly procurved, posterior row more strongly procurved. AME largest and circular, other eyes slightly smaller and elliptical. All eyes hyaline, surrounded by dark pigment ( Fig. 6f View Figure 6 ). Tapetum in lateral eyes canoe- shaped.

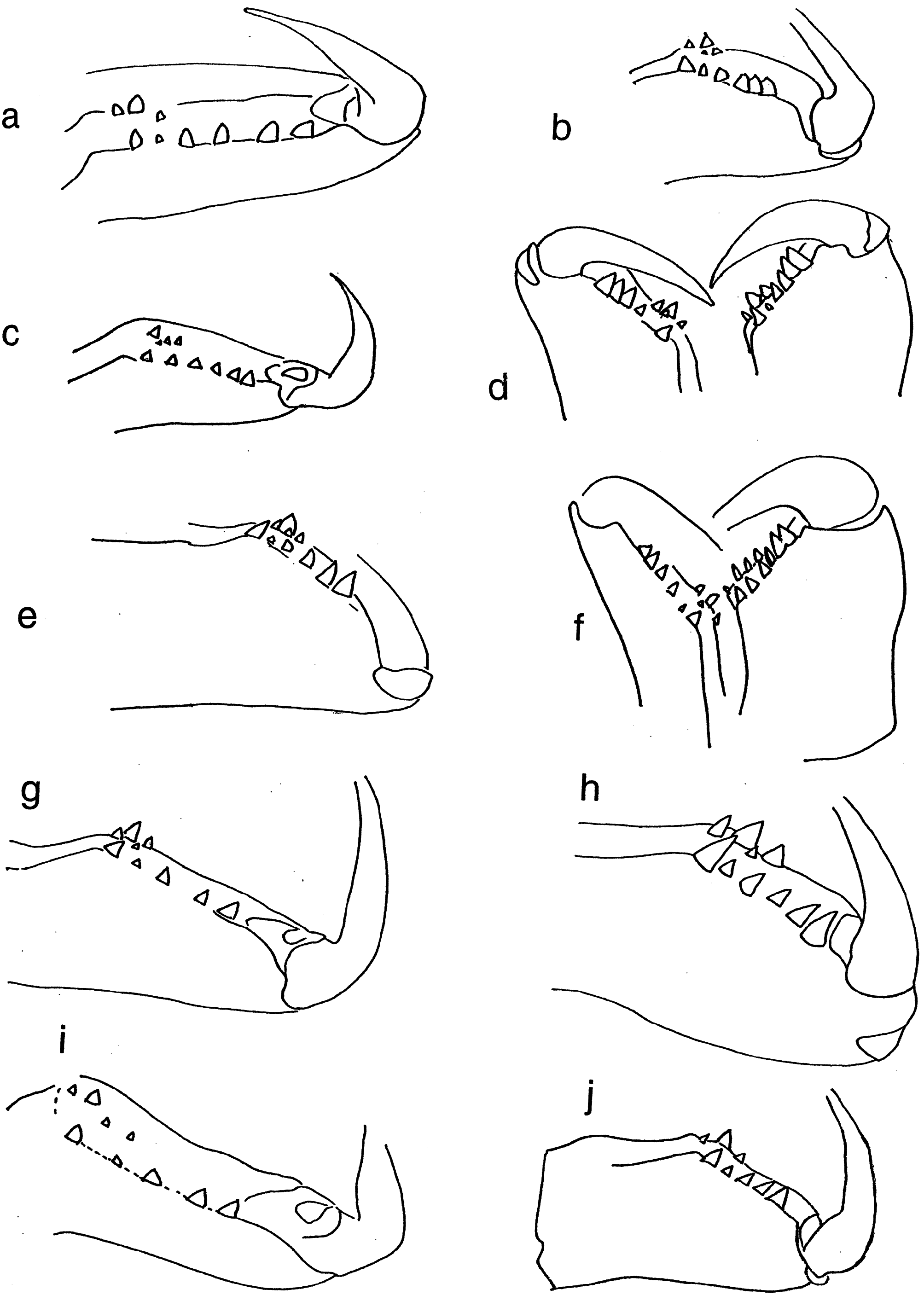

Chelicerae. Robust and long, extending ventrally well below the level of the sternum. Distinct boss present in most species. Two pairs of prominent frontal bristles present and usually crossing each other in front of chelicerae ( Fig. 6d View Figure 6 , 13d View Figure 13 ). Cheliceral retromargin with more teeth (5–8) than promargin (2–4). Cheliceral teeth may be variable within species ( Fig. 8a–j View Figure 8 ) and even from left to right in specimens ( Fig. 8f View Figure 8 ). Cheliceral groove with or without transverse ridges. Fangs with or without serrations.

Legs. Formula 1,4,2,3. Superior claws similar, strongly pectinate, inferior claw with 2–3 teeth. Single row of 4–8 trichobothria on tarsus, decreasing in length proximally. Tarsal organ simple, pyriform, sited apically beyond last trichobothrium. 4th metatarsus longest leg segment. First tibia often longer than 1st metatarsus. Trochanters unnotched.

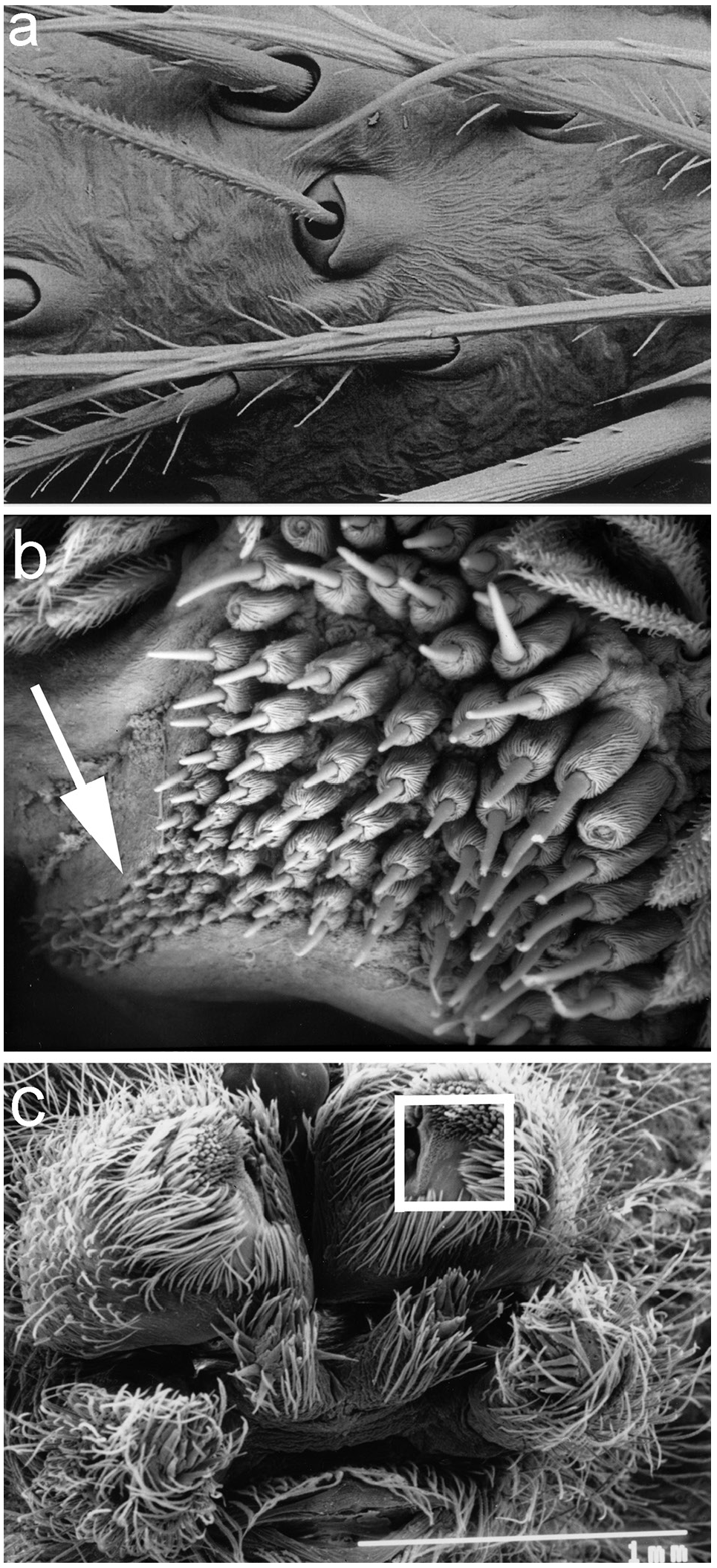

Hairs. Hair types present include plumose, ciliate and “pseudofeathery”. Pseudofeathery hairs ( Fig.3b View Figure 3 , upper right) differ from feathery hairs in having shorter tines which project from more than one plane.

Male palp. Cymbium with long digitiform portion at least twice and up to six times as long as the diameter of the palpal bulb. Single row of 2–7 trichobothria present ( Fig. 3a View Figure 3 ) decreasing in length proximally. Median apophysis absent. Conductor stalked or T-shaped. Conductor tip sclerotized, spine-like, twisted or bent. Both sides of the conductor may equally form the conductor tip or the ventral side may be dominant. Secondary conductor absent. Embolus long, curved and filiform, arising prolaterally to retrolaterally. Tibia with 2–3 apophyses. Retrolateral tibial apophysis spine-like, tapering, bent or curved. Ventral apophysis, when present, lobe, cup or leaf-like. Retroventral apophysis, when present, finger-like with long, terminal brush of curved bristles. Retrodorsal apophysis, when present, simple and sclerotized.

Epigyne. Strongly sclerotized, paired copulatory openings separated by scape with or without lateral extension. Spermathecae large. Insemination ducts weakly or strongly convoluted. Diverticula often present at junction with spermathecae. Epigynal atria may or may not be plugged. Appearance of external epigyne variable even within species ( Fig. 11a–l View Figure 11 ).

Spinnerets. Distinct overflow or tail region of small spigots prolaterally on anterior lateral spinnerets in most species ( Fig. 3b View Figure 3 ). Colulus single, flat, semi-circular, clothed in hairs.

Tracheal system. Four unbranched tubes, confined to the abdomen.

Web. Platform sheet web with labyrinth above and retreat to side through silken funnel, with or without a burrow ( Fig. 7h View Figure 7 ). Spider runs on top of sheet. Silk is ecribellate and nonsticky. Egg sacs with thick layer of soil or debris hung by thread of silk from roof of burrow. Males may or may not cohabit with penultimate females.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Corasoides Butler, 1929

| Humphrey, Margaret 2017 |

Corasoides

| Wheeler, W 2016: 12 |

| Platnick, N 1997: 609 |

| Platnick, N 1993: 541 |

| Davies, V. T 1988: 70 |

| Brignoli, P 1983: 467 |

| Main, B 1982: 92 |

| Lehtinen, P 1967: 225 |

| Bonnet, P 1956: 1925 |

| Roewer, C 1954: 61 |

| Neave, S 1939: 833 |

| Butler, L 1929: 42 |