Symphurus orientalis (Bleeker, 1879)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3620.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7B363037-12FA-4C2E-A219-0040FA12BCC6 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5624215 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B887E3-FFBC-E567-A8AA-FE608FA85168 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Symphurus orientalis (Bleeker, 1879) |

| status |

|

Symphurus orientalis (Bleeker, 1879) View in CoL

( Figs.1–5 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2. A View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 ; Tables 1–2 View TABLE 1 View TABLE 2 )

Aphoristia orientalis Bleeker, 1879: 31 , Pl. 2 (fig. 1) ( Japan; description, illustration of holotype).

Symphurus orientalis .— Jordan and Snyder 1901: 122 (listed; questionable occurrence, Japan). Jordan and Starks 1906: 243 (synonymy; description based on Bleeker (1879); doubted validity of species; transfer to Symphurus ; coasts of Japan, north of Vladivostok, based on Schmidt (1904)). Jordan et al. 1913: 335 (listed in catalogue; both coasts of Japan, off Vladivostok, based on Schmidt (1904)). Hubbs 1915: 496 (brief description; one specimen, Suruga Gulf, Japan). Mori 1928: 8 (listed, Korea). Chu 1931: 94 (listed, China). Wu 1932: 162 (synonymy; listed, China).?Fowler 1934: 223 (synonymy; redescription; Chihli, Peking, China and Japan; figure). Mori and Uchida 1934: 33 (listed; Korea). Taranetz 1937: 148 (in key). Okada 1938: 270 (listed; Honshu, Japan, Korea, and Vladivostok). Okada and Matsubara 1938: 439 (in part; brief morphological information for key; counts; off Japan, Pusan and Vladivostok). Chabanaud 1939: 27 (listed, world catalogue of flatfishes). Mori 1952:183 (listed, Pusan, Korea). Matsubara 1955: 1287 (in part) (brief data on meristic and morphometric features; Suruga Bay, Owase, Kochi, Japan and Pusan). Kamohara 1958: 64 (listed; Suruga Bay to Kochi Prefecture, Japan; and Korea). Ochiai 1959: 217 (in part) (redescription based on composite series of specimens; meristic and morphometric data following Matsubara (1955); figure; 200 m; China Sea, Yellow Sea, and Pacific side of southern Japan). Chyung 1961: 657 (in part) (redescription based on Ochiai (1959); Korea). Ochiai 1963: 102 (in part) (English edition of Ochiai (1959)). Chen and Weng 1965: 102 (in part? likely more than one species included in account; Tungkong, Taiwan; brief redescription). Chen 1969: 225, 226 (in part?) (brief description for identification key; follows Chen and Weng (1965); figure; Dong-Gang, Taiwan). Chyung 1977: 582 (listed; Pusan, Korea).?Son 1980 (listed; east coast of Korea, cited from Kim and Choi (1994)). Yasuda et al. 1981: 19, 569 (local name in several languages). Amaoka 1982: 302–3, 408 (redescription based on one specimen; color photograph; Tosa Bay, Japan).?Shen 1983: 107 (in part) (brief redescription possibly based on composite series of specimens; Taiwan). Shen 1984: 581 (in part) (redescription based on composite series of specimens; figure; in key; Taiwan). Ochiai 1984: 356 (in part) (redescription based on composite series of specimens following that of Ochiai (1959); figure; Japan, Suruga Bay to Yellow Sea, East China Sea). Chen and Yu 1986: 830 (in part) (listed; brief description for key; Taiwan). Shen 1986: 264 (Chinese, Japanese names). Li 1987: 513 (listed; figure; eastern Yellow Sea to northern South China Sea). Ochiai 1987: 931 (in part) (description following Ochiai (1959); color figure; Suruga Bay, Yellow Sea, East China Sea). Ochiai 1988: 342 (in part) (Japanese version of Ochiai (1984)). Ochiai 1989: 222 (in part) (description following Ochiai (1959); color figure; Suruga Bay, Yellow Sea, East China Sea). Munroe 1992: 374, 379 (ID pattern; meristic information). Lindberg and Federov 1993: 207 (mentioned in footnote; Japan side, sea of Japan). Shen 1993: 581 (in part) (redescription based on composite series of specimens; black and white photo not this species; Taiwan). Wang 1993: 115 (listed, South China Sea). Kim and Choi 1994:810 (no specimens; description based on composite series of specimens following Ochiai (1959); Korea (based on Son 1980)). Li and Wang 1995:380 (no specimens; redescription based on composite series of specimens following Ochiai (1959); illustrations; in key; China). Sakamoto 1997:684 (in part; more than one species included in brief account; color photo is not S. orientalis ; 200–400 m; Japan, East China Sea, Yellow Sea). Munroe and Amaoka 1998: 389 (discussed confusion surrounding species concept; distinguished from S. hondoensis ; Japan). Eschmeyer 1998: 1248, 2436 (literature; listed as valid species). Evseenko 1998: 61 (vertebral count; depth of occurrence; phylogenetic information of Pleuronectiformes ). Schwarzhans 1999:366 (description and illustration of otoliths; Japan). Yamada 2000: 1392 (in part) (brief redescription based on composite series of specimens following Ochiai (1959); in key; illustration; 200–400 m; Pacific coast Japan, East China Sea, Yellow Sea). Munroe 2000: 646 (listed, South China Sea). Lin 2001: 458 (listed, China’s seas including northeastern Yellow Sea to north of South China Sea). Munroe 2001: 3895 (listed, West Central Pacific). Shinohara et al. 2001: 337 (listed, Tosa Bay, Japan). Yoda et al. 2002: 29 (listed; Japanese, English names). Yamada 2002:1392 (in part) (English edition of Yamada (2000)). Youn 2002:441, 690 (in part) (brief redescription; in key; Korea). Kim et al. (2005): 490 (in part) (brief redescription; listed, Korea; photograph not of this species). Shinohara et al. 2005: 443 (listed, off Ryukyu Islands, Japan). Liu 2008: 1057 (listed, China, in eastern part of Yellow Sea and South China Sea; off Japan). Munroe and Hashimoto 2008: 44 (comments on misidentifications; comparisons with S. thermophilus ). Lee et al. 2009b: 57 (compared with S. multimaculatus ). Shen and Wu 2011: 763 (brief redescription with illustration; Taiwan).

Symphurus arientalis (Bleeker) .—Minami 1988:962 (in part; meristic data follows that of Ochiai (1959); description of larval stages; Japan).

Symphurus orientulis (Bleeker) .—Lin 1994: 747 (listed, China’s seas including northeastern Yellow Sea to north of South China Sea).

Symphurus novemfasciatus Shen and Lin, 1984: 8 , Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 (based on two specimens; color photograph; Tung-Kong (=Dong- Gang), Taiwan). Shen 1984:141 (after Shen and Lin (1984); description, color figure; Taiwan; compared with S. septemstriatus (Alcock)) . Shen 1986: 264 (listed; Chinese name). Chen and Yu 1986: 831 (listed; brief description for key). Munroe 1992: 379 (listed in table; meristic features following those in original description). Shen 1993: 581 (description based on Shen and Lin (1984), color photograph; Taiwan). Lin 1994: 747 (listed, sandy flat, southern Taiwan). Li and Wang 1995: 383 (no specimens; description based on Shen and Lin (1984); black and white photo; in key). Eschmeyer 1998: 1204, 2436 (literature; listed as valid species). Munroe 2000: 646 (listed; South China Sea). Liu 2008: 1057 (listed; off Dong-Gang, southwestern Taiwan). Ho and Shao 2011:63 (listed; type catalogue; Taiwan). Shen and Wu 2011: 763 (brief description with color photo).

Symphurus cf. orientalis (not of Bleeker).—Sowerby 1930: 182 ( Symphurus sp. listed in Schmidt (1904) likely a species of Cynoglossus ). Shen 1984: 141 (compared specimen identified as S. strictus Gilbert with S. orientalis sensu Chen and Weng (1965) ; Taiwan).?Fourmanoir 1985: 50 (three specimens, Philippine Islands). Hashimoto et al. 1988: 87 (Kaikata Caldera, west of Chichijima Island, Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands). Hashimoto et al. 1995: 585 (hydrothermal vents, Minami-Ensei Knoll, Mid-Okinawa Trough, Western Pacific). Ono et al. 1996: 223 (hydrothermal vents, Kaikata Seamount near Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands, South Japan). Fujikura et al. 2002: 24 (hydrothermal vent, Okinawa Trough).

Symphurus orientalis (not of Bleeker). Ohashi and Motomura 2011: 115 (brief description from single specimen; 70–100 m; Shibushi Bay, Kagoshima).

Neotype. BSKU 44238, mature female, 91.0 mm SL; Tosa Bay, off Kochi, Japan; bottom trawl, 300–400 m; collected by O. Okamura, 13 Nov 1987.

Counted and measured. 91 specimens (54.7–109.0 mm SL). Taiwan, off northeastern coast. ASIZP 72344, mature female, 77.0 mm SL; 24º49.22’N, 121º58.50’E, T.-W. Wang, 23 Aug 2007. ASIZP 72345, male, 77.0 mm SL; 24º52.17’N, 121º57.53’E, T.-W. Wang, 23 Aug 2007. ASIZP 72346, mature female, 81.7 mm SL; 24º52.17’N, 121º57.53’E, T.-W. Wang, 23 Aug 2007. ASIZP 72347, male, 77.1 mm SL; 24º52.17’N, 121º57.53’E, T.-W. Wang, 23 Aug 2007. ASIZP 67634, mature female, 93.5 mm SL; Nanfang-Ao fish port, M.- Y. Lee, 6 Jan 2007. Taiwan, off northeastern coast, in landings at Da-Shi fish port. ASIZP 72340, 2 mature females, 87.8–91.0 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 23 Aug 2007. ASIZP 72372 ( JN678742 View Materials and JN678777 View Materials ), mature female, 72.9 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72373 ( JN678743 View Materials and JN678778 View Materials ), mature female, 86.0 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72374 ( JN678744 View Materials and JN678779 View Materials ), male, 74.1 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72375 ( JN678745 View Materials and JN678780 View Materials ), mature female, 91.3 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72376 ( JN678746 View Materials and JN678781 View Materials ), male, 60.1 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72377 ( JN678747 View Materials and JN678782 View Materials ), male, 64.0 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72378 ( JN678748 View Materials and JN678783 View Materials ), mature female, 88.8 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72379 ( JN678749 View Materials and JN678784 View Materials ), male, 83.3 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72380 ( JN678750 View Materials and JN678785 View Materials ), mature female, 78.6 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. ASIZP 72381 ( JN678751 View Materials and JN678786 View Materials ), mature female, 75.3 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 30 Dec 2009. NMMB–P 1663, male, 96.4 mm SL; Y.-M. Ju, 9 Sep 2003. NMMB–P 6127, mature female, 89.2 mm SL; Y.-M. Ju, 8 May 2003. NMMB–P 6184, male, 94.7 SL; Y.-M. Ju, 8 May 2003. NMMB–P 6186, mature female, 85.6 mm SL; Y.-M. Ju, 8 May 2003. NMMB–P 8631, 2 mature females, 78.8–89.0 mm SL; T.-M. Ju, 18 Jun 2005. NMMB–P 9114, 10 (2 exam., 1 male and 1 immature female), 67.1–78.2 mm SL; Ta-Shi (=Da-Shi) fish port, H.-W. Chen, 7 Aug 2008. NMMB–P 7484, mature female, 80.8 mm SL; Y.-M. Ju, 16 Apr 2004. Eastern Taiwan, off Su-ao. ASIZP 65666, male, 67.7 mm SL; 24º47.75’– 24º48.01’N, 122º00.09’– 122º02.09’E, ORE beam trawl, 265–352 m, Fishery Researcher I, OCP 273, 13 Jun 2005. ASIZP 66767, 4 (2 exam., females), 66.9–88.7 mm SL; 24º55.11’– 24º57.47’N, 122º04.73’– 122º05.43’E, beam trawl, 267–430 m, Fishery Researcher I, CP 291, 8 Aug 2005. ASIZP 66821, 4 (3 exam., male and an immature and mature female), 71.4–83.1 mm SL; 24º57.07’– 24º58.27’N, 122º04.61’– 122º05.57’E, beam trawl, 236–272 m, Fishery Researcher I, CP 292, 8 Aug 2005. ASIZP 66898, 10 (4 exam. 2 males, 1 immature and 1 mature female), 65.7–79.4 mm SL; 24º55.70’– 24º57.23’N, 122º04.30’– 122º04.81’E, beam trawl, 212–275 m, Ocean Researcher I, CP 290, 28 Aug 2004. Taiwan, off southwestern coast, in landings at Dong-Gang fish port. ASIZP 67650, male, 76.5 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 4 Jul 2007. ASIZP 67651, male, 83.8 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 4 July 2007. ASIZP 67652, male, 82.5 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 4 Jul 2007. ASIZP 67653, mature female, 80.4 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 4 Jul 2007. ASIZP 72341, 2 males, 72.1–81.1 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 28 May 2008. ASIZP 72342, 6 (4 males and 1 immature and 1 mature female), 69.1–84.2 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 28 May 2008. ASIZP 72556 ( JN678752 View Materials and JN678787 View Materials ), male, 79.1 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 July 2011. ASIZP 72557 ( JN678753 View Materials and JN678788 View Materials ), immature female, 75.3 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72558 ( JN678754 View Materials and JN678789 View Materials ), immature female, 68.7 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72559 ( JN678755 View Materials and JN678790 View Materials ), immature female, 62.6 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72560 ( JN678756 View Materials and JN678791 View Materials ), male, 76.1 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72561 ( JN678757 View Materials and JN678792 View Materials ), male, 62.8 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72562 ( JN678758 View Materials and JN678793 View Materials ), male, 69.7 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72563 ( JN678759 View Materials and JN678794 View Materials ), male, 80.5 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72564 ( JN678760 View Materials and JN678795 View Materials ), male, 61.9 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. ASIZP 72565 ( JN678761 View Materials and JN678796 View Materials ), mature female, 72.3 mm SL; M.- Y. Lee, 21 Jul 2011. NMMB–P 3714, male, 72.1 mm SL; Dong-Kang (=Dong-Gang) fish port, J.-H. Wu, 2 May 2002. NMMB–P 5776, 2 mature females, 77.2–81.4 mm SL; Dong-Kang (=Dong-Gang) fish port, Y.-M. Ju, 13 Mar 2003. NMMB–P 6222, mature female, 90.9 mm SL; Tong-Kong (=Dong-Gang) fish port, H-C. Ho, 5 Jul 2007. NMMB–P 7914, male, 85.9 mm SL; Y-M. Ju, 11 Jun 2004. NMMB–P 8147, mature female, 76.3 mm SL; Y.-M. Ju, 11 Jun 2004. NMMB–P 6222, 3 (2 males and 1 mature female), 61.9–82.6 mm SL; Tong-Kong (=Dong-Gang) fish port, C-W. Chang, 27 Aug 2008. NTUM 0 4564, Holotype of S. novemfasciatus , mature female, 79.9 mm SL, Tung-kong (=Dong-Gang), S.-C. Shen, 1 Feb 1980. Taiwan, off southwestern coast. NMMB–P 7615, 2 mature females, 65.4–78.8 mm SL; Kao- Hsung, Y.-M. Ju, 4 Jul 2004. NMMB–P 3713, 2 mature females, 76.8–80.2 mm SL; Fon-Kan fish port, 200 m, J.- H. Wu, 2 Aug 2001. South China Sea. ASIZP 66881, 2 (male and mature female), 72.9–77.8 mm SL; Off Siao Liouciou, 22º21.64’– 22º22.29’N, 120º11.55’– 120º13.28’E, mini-beam trawl, 336–395 m, Ocean Researcher I, PCP 348, 9 Mar 2006. Japan. Tosa Bay, off Kochi, in landings at Mimase fish port. BSKU 341, mature female, 91.8 mm SL; 11 Apr 1951. BSKU 617, male, 82.3 mm SL; 5 Feb 1951. BSKU 618, mature female, 81.2 mm SL; 5 Feb 1951. BSKU 807, male, 92.5 mm SL; 19 Feb 1951. BSKU 808, male, 86.2 mm SL; 19 Feb 1951. BSKU 810, male, 91.7 mm SL; 19 Feb 1951. BSKU 1585, mature female, 96.3 mm SL; 20 Jan 1952. BSKU 3457, mature female, 91.2 mm SL; 6 Dec 1953. BSKU 40990, male, 70.4 mm SL; off Saga, traditional bottom trawl, 26 Feb 1985. Tosa Bay, off Kochi. BSKU 67756, male, 58.5 mm SL; R/V Kotaka-maru, 25 Jul 2003. BSKU 69970, 2 (exam. 1, male), 54.7 mm SL; 200 m, R/V Kotaka-maru, 7 Oct 2003. BSKU 88734, male, 68.7 mm SL; in landings at fish port, 3 Mar 2006. Off Murado Cape, Kochi. BSKU 3528, male, 109.0 mm SL; 1953. Suruga Bay. NSMT- P 7471, mature female, 97.3 mm SL; 16–20 Sep 1968. NSMT-P 49992, male, 74.5 mm SL; Off Heda, 245–440 m, 34º59.74’N, 138º45.17’E, 10 Nov 1996. NSMT-P 78389, mature female, 86.3 mm SL; 300–400 m, 1 Apr 1986. USNM 77066, male, 56.4 mm SL; 270–520 m, 16 Oct 1906.

Counted. 2 specimens (31.4–33.8 mm SL). ASIZP 72358 ( JN678762 View Materials and JN678797 View Materials ), male, 33.8 mm SL; off Kochi, Tosa Bay, Japan, 200 m, R/V Toyohata-maru, 17 Jun 2009. ASIZP 72359 ( JN678763 View Materials and JN678798 View Materials ), male, 31.4 mm SL; off Kochi, Tosa Bay, Japan, 200 m, R/V Toyohata-maru, 17 Jun 2009.

Diagnosis. Symphurus orientalis is distinguished from all congeners by the combination of: a predominant 1–2–2–2–2 ID pattern, 12 caudal-fin rays, 9 abdominal vertebrae, 52–55 total vertebrae, four hypurals, 96–101 dorsal-fin rays, 82–89 anal-fin rays, 87–99 longitudinal scale rows, 37–42 transverse scales, 18–22 scale rows on the head posterior to the lower orbit, and usually with 5–11 distinct, wide (covering 4–8 scales), complete or incomplete dark, blackish-brown crossbands on the ocular side, an alternating series of rectangular blotches and unpigmented areas (both extending from base to tip of fin) throughout entire lengths of dorsal and anal fins, uniformly white blind side, and conspicuous bluish-black peritoneum.

Description. Symphurus orientalis is a medium-sized species reaching sizes to approximately 109 mm SL. Meristic characters are summarized in Table 1 View TABLE 1 . Predominant ID pattern 1–2–2–2–2 (83/ 91 specimens). Caudal-fin rays 12 (two specimens with 11). Dorsal-fin rays 96–101. Anal-fin rays 82–89. Pelvic-fin rays 4. Total vertebrae 52–55; abdominal vertebrae 9(3 + 6). Hypurals 4. Longitudinal scale rows 87–99. Scale rows on head posterior to lower orbit 18–22. Transverse scales 37–42.

Proportions of morphometric features are presented in Table 2 View TABLE 2 . Body relatively deep and moderately elongate; maximum depth in anterior one-third of body usually at point between anus and fourth anal-fin ray, with moderate taper posteriorly from anus to posterior body margin. Preanal length smaller than body depth. Head moderately short and wide; head width slightly shorter than body depth, and much greater than head length (HW/HL= 1.05–1.28, x = 1.12). Upper head lobe wider than lower head lobe (UHL/LHL= 1.02–1.51, x = 1.18); slightly shorter than postorbital length. Lower lobe of ocular-side opercle wider than upper opercular lobe; posterior margin of lower lobe projecting slightly beyond posterior margin of upper opercular lobe. Snout moderately short, slightly rounded to obliquely blunt anteriorly, its length greater than eye diameter (SNL/ED= 1.39–2.11, x =1.62). Dermal papillae present, but not well developed, on blind-side snout. Ocular-side anterior nostril tubular and short, usually not reaching anterior margin of lower eye when depressed posteriorly. Ocular-side posterior nostril a small, rounded tube located on snout just anterior to interorbital space. Blind-side anterior nostril tubular, short, easily distinguishable from dermal papillae; blind-side posterior nostril a shorter and wider, posteriorly-directed, tube situated posterior to vertical at posterior margin of jaws. Jaws long and slightly arched; upper jaw length longer than snout length; posterior margin of upper jaw usually extending to point between verticals through anterior margin of pupil and midpoint of lower eye. Ocular-side lower jaw without fleshy ridge. Chin depth slightly shorter than, or equal to, snout length. Eyes moderately large and oval, separated by three to four rows of small ctenoid scales in narrow interorbital space. Eyes usually equal in position, or upper eye slightly in advance of lower eye. Pupillary operculum absent. Dorsal-fin origin located at point between verticals through anterior margin of upper eye and anterior margin of pupil of upper eye; predorsal length moderately short. Anteriormost dorsal-fin rays slightly shorter than more posterior fin rays. Scales absent on both sides of dorsal- and anal-fin rays. Pelvic fin moderately long; longest pelvic-fin ray, when extended posteriorly, usually reaching base of first to third anal-fin ray. Posteriormost pelvic-fin ray connected to anal fin by delicate membrane (torn in many specimens). Caudal fin relatively long, with several rows of ctenoid scales on base of fin. Body with numerous, strongly ctenoid scales on both sides.

Character Neotype NTUM 0 4564 Examined Specimens

n Range Mean ± SD Teeth present and recurved slightly inwards on all jaws, but better developed on blind-side jaws. Ocular-side premaxilla and dentary with single row of sharply pointed, well-developed teeth. Blind-side premaxilla with two to four rows of sharp, recurved teeth. Blind-side lower jaw with three to five rows of well-developed teeth.

Coloration of fresh-caught specimens ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Body pigmentation generally similar for both sexes at all sizes. Ocular-side background coloration generally straw-colored to dark-brown, usually with 5–11 distinct, wide (covering 4–8 scales), complete or incomplete, dark blackish-brown, crossbands; crossbands not continued onto dorsal and anal fins; some specimens with crossbands faded and indistinct or with uniformly brown pigmentation without crossbands. Anteriormost crossband on body region between opercle and vertical through anus; successive crossbands present on mid-body region to caudal-fin base. External surface of abdominal area usually bluish-black on both sides of body, but sometimes with same general coloration as that of ocular-side body (because darker peritoneal pigment obscured by abdominal wall and not visible externally). Background coloration of ocular-side head generally similar to that on body. Ocular-side snout light yellow. Ocular-side lips and chin region uniformly yellow to brown, margins of lips pigmented with small black chromatophores. Ocular-side anterior nostril brown. Upper aspects of eyes and eye sockets light blue; pupils bluish-black. Outer surface of ocular-side opercle yellow to brown, usually with same background coloration as that of head and body. Inner surface of ocular-side opercle and isthmus unpigmented.

Blind side generally white to light yellow with bluish-black peritoneum showing through abdominal musculature. Outer surface of blind-side opercle uniformly white to light yellowish. Inner surface of blind-side opercle unpigmented.

Fin rays of dorsal, anal, and pelvic fins uniformly yellow to brown; basal regions of fin rays and membranes covering fin rays light yellow, with diffuse scattering of yellow to brown melanophores covering entire fin membranes on both sides of fins. Dorsal and anal fins throughout their lengths with alternating series of darkly streaked and lightly pigmented fin rays. Basal margins of fin rays and associated fin membranes on blind side light yellow to light brown.

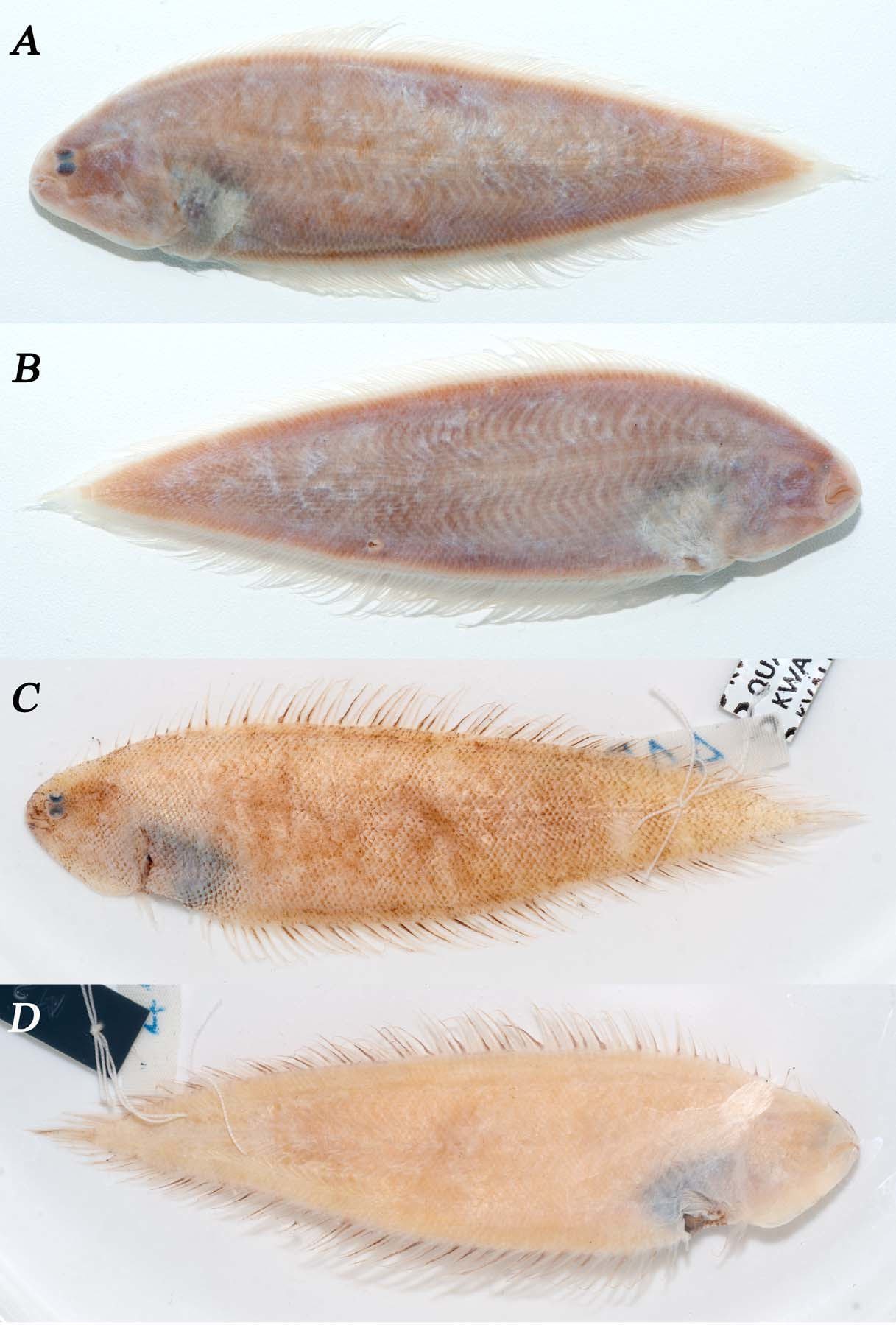

Coloration of recently preserved specimens ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2. A ). Similar to that of freshly-caught fishes. Specimens stored in preservative for decades usually mostly faded and with only remaining pigmentation consisting of the bluish-black eye sockets and black peritoneum.

Size and sexual maturity. 94 specimens range in size from 31.4 to 109.0 mm SL. Females (n = 49; 31.4–103.4 mm SL) and males (n = 45, 33.8–109.0 mm SL) attain similar sizes. Nine females (31.4–77.5 mm SL) are immature and show only slight elongation of the ovaries; 40 females ranging in size from 65.4 to 103.4 mm SL are mature with elongate ovaries, 29 of these (65.4–103.4 mm SL) are mature with elongate ovaries, but are nongravid, while another 11 females, ranging from 75.9 to 97.3 mm SL, are gravid.

Distribution. Symphurus orientalis is known from voucher specimens taken off the continental shelf and upper continental slope including captures in Japanese waters at Suruga Bay, Tosa Bay, and the Pacific side of southern Japan; also in the East China Sea in the Okinawa Trough; and from several locations off Taiwan including off I-lan, off northeastern and southwestern Taiwan, and in the South China Sea off Dong-Gang, Taiwan ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ). Based on voucher specimens, this species occurs at depths ranging from 200 to 520 m throughout its geographic range, with most captures usually occurring between 250 and 400 m. Symphurus orientalis is frequently taken on muddy substrata or a mixture of mud-sand substrata.

Literature accounts reporting tonguefishes identified as S. orientalis list this species from a wider geographic range including the Philippines (Fourmanoir 1985), off mainland China, off Korea, and off Vladivostok, Russia. Because of uncertainties involving specimens previously identified as S. orientalis , reports of S. orientalis from some of these locations are questionable.

We did not examine the three specimens from the Philippines that Fourmanoir (1985) identified as S. orientalis , which were taken at similar depths (299–320 m) to those occupied by S. orientalis . Counts he reported for these specimens are at the low ends of ranges of those for S. orientalis from Japan and Taiwan, respectively. Possibly, these specimens are S. orientalis . However, they need to be compared with other specimens from the Philippines with 12 caudal-fin rays including those that Chabanaud (1955) identified as S. septemstriatus and others representing another nominal species of uncertain status that we (Lee & Munroe unpubl. data) have identified among specimens from the Philippine Islands. Both nominal forms are similar to S. orientalis , but they differ from it in several of their morphometric features.

Although several studies (Chu 1931; Sowerby 1930; Wu 1932; Fowler 1934; Li 1987; Lin 1994; Liu 2008) reported the geographic distribution of S. orientalis to include waters off mainland China (Bei-Jing and other localities), these records seem doubtful and none are vouchered by specimens. Li and Wang (1995) in their work on flatfishes inhabiting Chinese waters commented that reported captures of S. orientalis from off mainland China were “suspect.” They, instead, listed the distribution of S. orientalis from Taiwan (based on Chen & Weng 1965) to the eastern part of the Yellow Sea and southern Japan. In an extensive study of fishes trawled at depths of 120–1100 m in the East China Sea between 26° and 33°N latitudes, Chengyu et al. (1986) did not report capturing this species, nor have recent collecting efforts off mainland China (X. Kong person. commun., 27 November, 2009) collected any Symphurus in the deepwater areas sampled off mainland China. Water depths off the coast of China are usually shallower than 100 m, and based on what we know concerning depth of capture of specimens of S. orientalis from other areas it seems unlikely to find S. orientalis in the waters off China.

Other studies (Mori 1928; Mori & Uchida 1934; Son 1980; Kim & Choi 1994 (based on Son 1980)) record S. orientalis from off the east coast of North Korea, or from Korean waters (Kim et al. 2005). Reported occurrences of S. orientalis in waters off the east coasts of North and South Korea are questionable because they are based, at least in part, on misidentified specimens. For example, identifications in Kim and Choi (1994) are based on data provided in Ochiai’s (1959) redescription of S. orientalis , which includes more than one species (see detailed comments below). Kim et al. (2005) in their illustrated book of Korean Fishes record S. orientalis from Korean waters, and provide a brief description with a color photograph of a specimen purported to be this species. However, their description of S. orientalis follows that of Ochiai (1959), and furthermore, the fish in the color photograph that they identify as S. orientalis is not that species. No voucher specimens were listed in any of the studies (Son 1980; Kim and Choi 1994; Kim et al. 2005) reporting S. orientalis from Korean waters so it is not now possible to determine if specimens included in those accounts are actually this species. Off South Korea and adjacent areas, such as the Yellow Sea, continental shelf depths are shallower than 150 m. These depths are shallower than those typically inhabited by S. orientalis (200 m and deeper) based on voucher specimens we examined. Most literature (Ochiai 1959; 1963; Amaoka 1982; Sakamoto 1997; Yamada 2000; 2002; Choi et al. 2002) as well as detailed collecting efforts in the Sea of Japan (Yeh 2001; Tian et al. 2006), the only known deeperwater area off Korea where S. orientalis would most likely be found based on depth of occurrence of voucher specimens we examined, have not reported capturing specimens of Symphurus from these waters nor do they include the Sea of Japan as a part of the geographic range of S. orientalis . Based on the numerous misidentifications of specimens and the lack of documented captures for this species, we conclude that reports of S. orientalis from Korean waters need confirmation with voucher specimens.

Several studies ( Jordan & Starks 1906; Jordan et al. 1913; Okada 1938) record S. orientalis from off Vladivostok based on Schmidt’s (1904) account of Symphurus sp. from this area. However, this locality record for S. orientalis is doubtful. Jordan and Starks did not examine any specimens of S. orientalis , including the specimen listed by Schmidt (1904). And reports of S. orientalis from this location are based only on the specimen listed in Schmidt (1904). However, Schmidt’s account of Symphurus sp. is problematic because it is based on an 85 mm juvenile specimen in poor condition that is missing most of its scales, has damaged fins with several fin rays broken, and because the description of this specimen includes so little useful diagnostic information that it can not be unequivocally determined even if it is based on a specimen of Symphurus , let alone a specimen that could be positively identified as S. orientalis , as suggested by its inclusion in the synonymy and distribution sections of Jordan and Starks’ (1906) account of S. orientalis . Even though Schmidt states that his specimen lacks a lateral line, which is a diagnostic feature for species belonging to Symphurus , it is possible that Schmidt could have examined a juvenile specimen of Cynoglossus that was missing its scales and thus appeared to lack a lateral line(s). For juvenile specimens of some species of Cynoglossus that have lost their scales, it is sometimes difficult to determine if they have 0, 1, or 2 lateral lines ( Jordan & Starks 1906; Munroe unpubl. data). Sowerby (1930), too, thought that Schmidt’s account of a specimen of Symphurus from off Vladivostok was actually a specimen of Cynoglossus . Based on information presented in Schmidt’s account of a specimen identified as Symphurus sp., we can not conclusively rule out the possibility that Schmidt had a specimen of Symphurus . However, if Schmidt had actually examined a specimen of Symphurus , we can confirm that this specimen belonged to a species other than S. orientalis because the reported number of dorsal-fin rays (75), if accurate, is well below the range of dorsal-fin rays observed in our specimens of S. orientalis (96–101; see Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). Thus, we conclude that reports of S. orientalis from off Vladivostok are suspect, if not erroneous. The record of S. orientalis from this area is based on the geographic distribution reported for S. orientalis that appeared in Jordan and Starks (1906). This record, in turn, relied on Schmidt’s (1904) report of an unidentified tonguefish specimen that we conclude is not very likely this species, if even a specimen of Symphurus . Records of symphurine tonguefishes from the continental shelf off Vladivostok need updating based on documented catches and reliable identifications of voucher specimens.

Remarks. The original description and illustration of the holotype of S. orientalis by Bleeker (1879: 31) clearly indicate that the holotype (and only specimen) is a symphurine tonguefish characterized by 12 caudal-fin rays and a banded pigmentation pattern. At the time of its description, S. orientalis was differentiated from other described species of Symphurus by its unique combination of number of dorsal- and anal-fin rays, scale counts and pigmentation pattern.

While the original description of S. orientalis contained sufficient information to diagnose this species from other described symphurine tonguefishes known at the time of its discovery, information contained in the original description has since proven inadequate to differentiate this from other similar nominal species described or discovered subsequent to Bleeker’s study. Also, because S. orientalis was known only from a single specimen, the range in values for diagnostically important morphological features were unknown for the species, and this uncertainty has undoubtedly contributed to the inadequate redescriptions of this nominal species appearing in works of subsequent ichthyologists. Further compounding this difficulty is the subsequent loss of the holotype specimen of S. orientalis , which has eliminated any possibilities of knowing additional diagnostic characters (i.e., ID pattern, vertebral counts) about Bleeker’s nominal species that would facilitate more detailed comparisons with other tonguefishes that have similar features to those reported for the holotype of S. orientalis .

Matsubara’s (1955) identification key provided a wide range of meristic counts and morphometric measurements for specimens purported to be S. orientalis . Ochiai’s (1959; 1963) redescription of S. orientalis followed the information provided in Matsubara (1955), but Ochiai’s study is more detailed and also provides catalogue numbers of the examined specimens. This is the primary reason that his redescription (Ochiai 1959; 1963) of S. orientalis has been widely cited as an authoritative work on this species and data from that study have often been repeated in subsequent reports of S. orientalis from western Pacific localities. However, recent discoveries (Lee & Munroe unpubl. data) of several additional nominal species in the western Pacific region that have some similarities to S. orientalis reveal that Ochiai’s redescription of S. orientalis likely combined morphological data for this species as well as that for one or more of these other nominal species. In continental shelf waters off Japan, two nominal species of Symphurus featuring 12 caudal-fin rays (same number as in S. orientalis ), but with fewer meristic features than those of S. orientalis [in fact, more similar to those of S. microrhynchus (Weber) , see Munroe & Marsh 1997], have recently been discovered (Lee & Munroe unpubl. data). Meristic data for one or both of these species were likely included in the key appearing in Matsubara (1955) and in the redescription of S. orientalis by Ochiai (1959; 1963) as evidenced by the wide ranges reported for several meristic features observed for these specimens (dorsal-fin rays 86–100, anal-fin rays 74–86, longitudinal scales 81–87). In contrast, specimens we identified as S. orientalis in our study, which represent specimens from localities spanning a wide geographic range, including Japan, have a much narrower, and higher range of values for dorsal- (96–101) and anal-fin rays (82–89), as well as different counts for longitudinal scales (87–99).

Chen and Weng (1965) recorded S. orientalis from Taiwanese waters. However, their report of this species from Taiwan is questionable because their redescription of S. orientalis indicates that specimens they identified as S. orientalis have 15 caudal-fin rays, whereas S. orientalis typically has only 12 caudal-fin rays (Bleeker 1879; Munroe 1992; this study). Unfortunately, specimens examined by Chen and Weng (1965) are lost, precluding possibilities of confirming whether the caudal-fin ray counts reported by Chen and Weng were in error. However, of the many specimens of Symphurus that we have examined, we have not found any specimens of species characterized by having 12 caudal-fin rays that had either 14 or 15 caudal-fin rays. We think that specimens examined by Chen and Weng were actually other species of Symphurus , such as S. bathyspilus Krabbenhoft and Munroe or S. multimaculatus Lee et al. (2009b) . These species, which occur in Taiwanese waters (Lee unpubl. data), differ from S. orientalis in having 14 caudal-fin rays, but are similar in their counts of dorsal- and anal-finrays.

In 1984, Shen and Lin (1984) described another nominal tonguefish species from southern Taiwan, S. novemfasciatus , based on two specimens featuring 12 caudal-fin rays and an ocular-side pigmentation pattern with nine crossbands. Perhaps misled by the erroneous caudal-fin ray counts reported earlier in Chen and Weng (1965) for specimens purported to be S. orientalis from Taiwanese waters, Shen and Lin (1984) did not compare their specimens with those of Chen and Weng, nor did they diagnose or compare their specimens with Bleeker’s description of S. orientalis from off Japan. Neither did they compare their specimens with those included in the redescription of S. orientalis by Ochiai (1959). In a later study, Shen (1984) mentioned some similarity between S. novemfasciatus and the “closely related” S. septemstriatus , but none of the other subsequent studies dealing with S. novemfasciatus (Shen 1993; Lin 1994) compared S. novemfasciatus with S. orientalis or any of the other previously-named species in this species complex (see further remarks below).

Because of the many similarities between S. orientalis and S. novemfasciatus , the status of this nominal species needed to be evaluated to determine if it is distinct from S. orientalis . Variations in meristic and morphometric features of 92 specimens of S. orientalis collected from different locations ranging from Japan to Dong-Gang, Taiwan, off northeast Taiwan, off Ping-tung, southwestern Taiwan including the type locality of S. novemfasciatus , and from the South China Sea were slight and no clinal trends in morphological variation were evident among these specimens. Detailed comparisons of the morphology and pigmentation of the holotype of S. novemfasciatus ( Fig. 2A, 2 View FIGURE 2. A B) with those from this larger series of specimens of S. orientalis reveal nearly complete overlap between the two nominal species in many features. Several important diagnostic characters, such as ID pattern or vertebral counts, could not be determined in the holotype of S. novemfasciatus because its skeleton has decalcified (precluding observing these features from a radiograph). Meristic features of S. novemfasciatus that overlap those of S. orientalis include fin-ray (caudal-fin rays 12 in both species; dorsal-fin rays 101 vs. 96–101 in S. orientalis ; anal-fin rays 88 vs. 82–89 in S. orientalis ) and scale counts (longitudinal rows 94 vs. 87–99 in S. orientalis ; transverse scales 39 vs. 37–42 in S. orientalis ). Likewise, proportions of many morphometric features of the holotype of S. novemfasciatus lie within ranges of those features recorded for S. orientalis ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ). Both nominal species have a relatively deep body (BD of S. novemfasciatus = 26.8% SL vs. 24.2–28.8 % in S. orientalis ), both have their preanal lengths shorter than their body depths (PAL 22.5% SL vs. 21–25.6% in S. orientalis ), both have a moderately short and wide head, with the head width just slightly less than the body depth and much greater than their head length (HW/HL = 1.15 vs. 1.05–1.28 in S. orientalis ). Other similarities between the two species include the width of the upper head lobe compared with that of the lower head lobe (UHL/LHL = 1.09 in S. novemfasciatus vs. 1.02–1.51 in S. orientalis ), shape and size of their short snouts (SNL 17.4% HL in S. novemfasciatus vs. 17.2–22.1% in S. orientalis ), and their small eyes (ED 11.3% HL in S. novemfasciatus vs. 9.7–12.6% in S. orientalis ). Additionally, these two nominal species have similar coloration. Ocular-side coloration was one feature that Shen and Lin (1984) considered diagnostic for S. novemfasciatus among its congeners. They considered the nine ocular-side crossbands of S. novemfasciatus to be a unique, diagnostically important, character for this species. However, Bleeker (1879) had much earlier indicated a banded coloration pattern for S. orientalis , and we also found that many specimens of S. orientalis from across the geographic range of this species, including southern Taiwan, feature 5–11 crossbands on their ocular sides.

To gain better understanding of the genetic divergence among tonguefishes that we identified as S. orientalis , including those from the type locality of S. novemfasciatus , we compared partial sequences of COI and 16S rRNA between specimens from Japan and northeast Taiwan. Genetic divergence among individuals from these widespread locations was shallow for both genes (only 0.12% K2P distance in the 16S and 0.22% K2P distance in the COI sequence data). If S. novemfasciatus were distinct from S. orientalis , much greater genetic divergence would be expected between these taxa. Ward et al. (2005; 2009), for example, suggested that, in fishes, an average K2P distance of less than 0.4% is within the range of variation expected within a species. The amount of divergence between S. novemfasciatus and S. orientalis (16S: S. novemfasciatus : 0.30% K2P distance, S. orientalis : 0.13%; COI: S. novemfasciatus , 0.26% K2P distance, S. orientalis : 0.27%) and between the nominal species (16S: 0.21% K2P distance, COI: 0.26%) is similar to that expected for populations within a species. Such shallow genetic divergence observed for populations of S. orientalis indicates a lack of structure among these widespread populations ( Taiwan and Japan), a finding which further supports the hypothesis that these populations belong to one panmictic species. Furthermore, the N-J trees ( Figs. 4–5 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 ) constructed from both the 16S rRNA and COI sequence data also show this lack of structure between populations representing these two nominal species and also indicate that these individuals are members of the same genetic lineage.

Based on nearly complete overlap in morphological features and the low amount of genetic divergence among specimens from Japan and Taiwan, all evidence indicates that only one species is represented by this material. These data strongly support recognizing S. orientalis (Bleeker) , with S. novemfasciatus as its junior subjective synonym.

Given the long history of confusion regarding the taxonomic status and identity of S. orientalis , it is necessary to designate a neotype to stabilize the nomenclature of this nominal species. Since the original description of S. orientalis (Bleeker) is based on a specimen from Japan, the following specimen is designated as the neotype of S. orientalis (Bleeker) : BSKU 44238 ( Figs 2 View FIGURE 2. A C, 2D): 91.0 mm SL; mature (not gravid) female; collected by O. Okamura, Nov 1987, from Tosa Bay off Kochi at a depth between 300 and 400 m. Meristic features of the neotype are: 1–2–2–2–2 ID pattern; 12 caudal-fin rays; 98 dorsal-fin rays; 87 anal-fin rays; 9(3+6) abdominal vertebrae; 54 total vertebrae; 4 hypurals; 94 longitudinal scales; 39 transverse scales; and 20 scale rows on the head from the posterior margin of its lower orbit to the posterior margin of the opercle.

Comparisons. Among Indo-Pacific Symphurus , in addition to S. orientalis (including S. novemfasciatus ), five other named species also feature 12 caudal-fin rays (Alcock 1891; Alcock 1896; Weber 1913; Chabanaud 1955; Chabanaud 1957). Of these, only S. septemstriatus , S. luzonensis , and S. fallax have similar fin-ray and/or vertebral counts to those of S. orientalis .

Symphurus septemstriatus is known from relatively few specimens collected in deep waters (260–730 m) of the Indian Ocean including the Andaman Sea, the Laccadive Sea off Colombo, Sri Lanka, and in the Gulf of Mannar (Alcock 1891; 1896; and 1899, respectively). Opportunities to directly study the types and other specimens of this species curated at the Zoological Survey of India were not available to us. Nor is there any published information on morphological features of this species for any other specimens from Indian Ocean localities beyond counts and measurements of the holotype (Norman 1928; Munro 1955). Records of this species and accompanying morphological data from specimens collected at localities beyond these Indian Ocean locations (e.g., the Philippines; in Chabanaud (1955)) may be that for S. septemstriatus , but these specimens require further study to determine their identity (Lee & Munroe unpubl. data). We do, however, have a photograph of the holotype of Aphoristia septemstriata , which provides some useful comparative information on this species. Based on our data, S. orientalis differs from S. septemstriatus in having more anal-fin rays (82–89 vs. 80 in S. septemstriatus ) and its upper head lobe is larger than the lower head lobe (UHL/LHL = 1.02–1.51 in S. orientalis vs. UHL/LHL <1.0 in S. septemstriatus ). The snout of S. orientalis is rounded or obliquely blunt anteriorly versus pointed and narrower in S. septemstriatus , and the migrated eye has a more medial position compared with that of S. septemstriatus , which has the migrated eye located closer to the dorsal margin of the head. Shen (1984) had noted a difference in number of ocular-side crossbands between his S. novemfasciatus (= S. orientalis ) and S. septemstriatus , however, when a larger series of S. orientalis are examined this apparent difference does not exist as the two species overlap completely in this feature.

Symphurus luzonensis is another nominal species of western Pacific deepwater tonguefish described from a single specimen that was collected off Luzon Island, Philippines (Chabanaud 1955). Chabanaud (1955) reported that this specimen had 10 abdominal vertebrae and 52 total vertebrae and thus only diagnosed his species from S. regani Weber , a species that has 10 abdominal vertebrae and a similar number of total vertebrae. A radiograph of the holotype of S. luzonensis , however, reveals that this species actually has 9 abdominal and 53 total vertebrae, and an ID pattern and fin-ray counts that are more similar to those of S. orientalis (Munroe 1992) . Symphurus orientalis differs from S. luzonensis in having more scales in a transverse row (37–42 vs. 34 in S. luzonensis ), a deeper body (BD 24.2–28.8% SL vs. 22.1% in S. luzonensis ), a wider upper opercular lobe (OPUL 21.0–31.4% HL vs. 18.9% in S. luzonensis ), larger HW/HL ratio (HW/HL = 1.05–1.28 vs. 0.99 in S. luzonensis ), and its dorsal-fin origin is located more anteriorly than is that of S. luzonensis .

Symphurus fallax Chabanaud is another poorly-known nominal species described from a small (45 mm SL), damaged, holotype specimen, which was collected at 397 m off Kei Island, Indonesia (Weber 1913). No photograph or illustration accompanied the original description of this nominal species (Chabanaud 1957), nor was any provided in Weber’s (1913) or Weber and de Beaufort’s (1929) accounts of the specimen, which they referred to as an unidentified species of Aphoristia or Symphurus , respectively. Further compounding problems with the identity of this nominal species is that Chabanaud did not return the holotype to the Zoological Museum of Amsterdam’s fish collection (Eschmeyer 2012). Thus, the only information on this species is that contained in the original description. Of interest is that in the description, Chabanaud did not differentiate his nominal species from S. orientalis , despite the fact that based on our assessments his species was morphologically similar to this congener, especially with respect to the numbers of caudal-fin rays. We found only minor differences in meristic features between S. orientalis and those reported for S. fallax (dorsal-fin rays 96–101 in S. orientalis vs. 95 in S. fallax ) and S. orientalis has a slightly deeper body (BD 24.2–28.8% SL vs. 22.0% in S. fallax ). Otherwise, little else differentiates these nominal species, a finding which questions the validity of S. fallax . Before arriving at a taxonomic decision regarding the status of this nominal species, more specimens from the type locality are needed to determine if S. fallax is valid and distinct from S. orientalis and S. septemstriatus .

Discussion

Most problems regarding the taxonomic status of many nominal, deep-water species of Symphurus occurring in Indo-Pacific waters are due to the limited amount and overall poor condition of many of the study specimens, incomplete and insufficient descriptions, and by an overall similarity in phenetic features among several of these nominal species (Munroe 1992; Munroe & Amaoka 1998; Munroe & Hashimoto 2008). Symphurus orientalis is now known from a comparatively large number (over 100) of preserved specimens identified by a consistent set of diagnostic features. Results of this study provide robust morphological data, a detailed description, and updated information on the geographic and bathymetric distributions of this species.

This study also resolves the taxonomic status of S. novemfasciatus Shen and Lin as it was shown that this nominal species is invalid based on the nearly complete overlap in morphological and pigmentation features between it and S. orientalis . In recent years, molecular tools (Tautz et al. 2003) including DNA barcoding (Hebert et al. 2003) and knowledge about DNA sequences have become more common in helping to resolve taxonomic problems involving closely-related species. With respect to most taxonomic groups, including some tonguefishes (Tunnicliffe et al. 2010), studies of DNA sequences have revealed that estimates of biodiversity at the species level that are based on morphological characters actually underestimate the real diversity represented among the specimens (see also Hebert et al. 2004; Ward et al. 2008; Teletchea 2009; Tornabene et al. 2010). Molecular tools have been especially valuable in discovering cryptic species present among specimens previously considered to represent only a single nominal species. Cryptic species show only minor differences in morphology, and these minor differences are largely ignored as insignificant features useful for identification. Among tonguefishes, one example of cryptic species was found among allopatric populations occurring on seamounts in the Pacific Ocean when Tunnicliffe et al. (2010) observed large genetic divergence in partial 16S rRNA (9.0%) and COI (14.2%) gene sequences between populations that had previously (Munroe & Hashimoto 2008) been considered as one species, S. thermophilus .

In light of these findings, we tested the hypothesis that two nominal species might be represented among specimens we studied: S. orientalis which inhabits marine waters from Japan to the Pacific side of Taiwan, and a second, cryptic species, S. novemfasciatus , with a more limited and allopatric distribution in the region of Dong- Gang, South China Sea. This hypothesis seemed plausible because these nominal species share so many similarities in their morphological features and pigmentation, but are geographically separated. The slight genetic divergences we found between populations hypothesized to represent S. novemfasciatus and S. orientalis , both in the partial 16S (0.21% K2P distance) and COI (0.26% K2P distance) gene sequences, indicated that S. novemfasciatus should not be considered a cryptic species. Rather, based on these results, close genetic similarity among these geographically separated populations ( Taiwan and Japan) supports conclusions based on morphological data that S. novemfasciatus is a junior subjective synonym of S. orientalis .

Despite improvements in our understanding of morphological and genetic variation in S. orientalis , a large need still remains for more reliable information on several important biological aspects of this species including its geographic and bathymetric distributions, diet, reproduction, life history demographics, microhabitat preferences, population density, and spatial distribution. Better definition of the species concept of S. orientalis and an improved understanding of the morphological variation within populations of this species should lead to more reliable identification of specimens of this and related species in the future. In turn, this should lead to improvements in data documenting its bathymetric and geographic distributions and should provide better insight into the ecology of this species.

From a systematics perspective on the genus Symphurus , now that the status of S. orientalis and S. novemfasciatus has been critically evaluated and resolved, the task of validating the status of similar, nominal species and other populations of Indo-West Pacific Symphurus can begin. Questions still abound considering the status and identity of S. luzonensis and S. fallax , which are known only from holotype specimens. It remains to be determined how many other Indo-West Pacific species, together with S. orientalis and S. septemstriatus , compose the species complex whose members are characterized by a 1–2–2–2–2 ID pattern, 12 caudal-fin rays and high meristic features. Further expeditions, both to locations where specimens of rare and poorly-known species were originally collected and also to those areas that have never been sampled, are needed to provide additional specimens to resolve the systematic problems surrounding these tonguefishes.

Acknowledgments

This work represents a portion of a collecting activities grant investigating the biodiversity and systematics of deep-sea fishes in Taiwanese waters supported by the National Science Council (NSC 96–2628–B–0 0 1–0 0 6–MY3 and NSC 99–2621–B–0 0 1–0 0 8–MY3) and awarded to K.-T. Shao, Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica. We thank H.-M. Yeh, Coastal and Offshore Resource Research Center, Fisheries Research Institute, who kindly provided trawl station data from research vessels. H.-C. Ho, P.-F. Lee, Y.-C. Liao and L.-P. Lin assisted with collecting specimens and kindly provided other specimens used in this study. K.-C. Hsu advised M.- Y. Lee regarding molecular aspects of this research study. A. Collins, NSL, kindly provided information and helpful editorial suggestions regarding molecular approaches used in this study. L.-P. Lin and C.-W. Chang assisted with loans and shipments of specimens. M. Nizinski provided assistance and support during M.- Y. Lee’s visit to the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. H. Endo, N. Nakayama, and R. Asaoka provided assistance and support during M.- Y. Lee’s visit to the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Kochi University. They also provided two important fresh specimens of S. orientalis from Japan to help with molecular comparisons. K. Matsuura and G. Shinohara provided loan of Suruga Bay specimens during M.- Y. Lee’s visit to the Department of Zoology, National Science Museum. K. Murphy (USNM) assisted with specimen and catalogue information. K. Nakaya, Hokkaido University, provided the photograph of the holotype of S. septemstriatus . K. Vinnikov, University of Hawaii at Manoa, graciously provided translations of Russian literature. L. Willis, NMFS-NSL, assisted with literature. H.-M. Chen provided comments on an early draft of the manuscript. M.- Y. Lee extends his appreciation to all members of the Laboratory of Fish Ecology and Evolution for their support, especially H. Lee for helping to draw the distribution map and assistance during this study.

TABLE 1. Frequency of meristic characters of Symphurus orientalis. Counts for the neotype (BSKU 44238) indicated by an asterisk (*); those of the holotype of S. novemfasciatus (NTUM 04564) indicated by a solid star ().

| ID Pattern | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2-2-2-2* | 1-2-3-2-2 | 1-2-2-2-1 | 1-3-2-2-2 | 1-2-1-2-2 | N | |

| 83 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 91 | |

| Dorsal-fin rays | ||||||

| 96 | 97 | 98* | 99 100 | 101 | N | |

| 12 | 11 | 23 | 23 11 | 12 | 92 | |

| Anal-fin rays | ||||||

| 82 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 87* 88 | 89 | N | |

| 2 8 | 19 | 15 | 26 17 4 | 1 | 92 | |

| Caudal-fin rays | Abdominal vertebrae | |||||

| 11 | 12* | N 3+6* | N | |||

| 2 | 92 | 94 93 | 93 | |||

| Total vertebrae | ||||||

| 52 | 53 | 54* | 55 | N | ||

| 5 | 27 | 50 | 9 | 91 | ||

| Longitudinal scale count | ||||||

| 87 88 89 | 90 | 91 92 93 | 94* 95 96 97 | 98 | 99 | N |

| 1 4 2 | 6 | 6 9 9 | 13 7 10 7 | 9 | 3 | 86 |

| Head scale count | ||||||

| 18 | 19 | 20* | 21 | 22 | N | |

| 5 | 31 | 33 | 16 | 1 | 86 | |

| Transverse scale count | ||||||

| 37 | 38 | 39* | 40 41 | 42 | N | |

| 7 | 21 | 21 | 24 12 | 1 | 86 |

TABLE 2. Morphometrics for the neotype (BSKU 44238) and examined specimens of Symphurus orientalis, including those for the holotype of S. novemfasciatus (NTUM 04564). SL in mm; characters 2 – 15 in % of SL; 16 – 23 in % of HL.

| 1. Standard length | 91.0 | 79.9 | 92 54.7–109.0 | 78.63±10.30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Body depth | 26.1 | 26.8 | 92 24.2–28.8 | 26.29±1.12 |

| 3. Trunk length | 84.2 | 82.9 | 90 80.3–85.1 | 82.93±1.14 |

| 4. Predorsal length | 2.9 | 3.6 | 90 2.4–4.5 | 3.44±0.42 |

| 5. Preanal length | 22.9 | 22.5 | 91 21.0–25.6 | 23.44±1.05 |

| 6. Dorsal-fin length | 97.0 | 96.4 | 90 94.8–97.6 | 96.54±0.47 |

| 7. Anal-fin length | 77.3 | 77.4 | 90 74.5–79.2 | 76.53±1.04 |

| 8. Pelvic-fin length | 8.0 | – | 80 5.8–9.2 | 7.54±0.89 |

| 9. Pelvic to anal length | 3.6 | 2.3 | 84 1.5–4.8 | 3.28±0.75 |

| 10. Caudal-fin length | 10.8 | 11.2 | 72 10.2–12.7 | 11.30±0.65 |

| 11. Head length | 17.7 | 19.7 | 92 17.4–21.6 | 19.62±1.02 |

| 12. Head width | 20.0 | 22.7 | 91 19.0–25.2 | 22.04±1.29 |

| 13. Postorbital length | 11.9 | 12.8 | 91 11.4–14.7 | 13.18±0.73 |

| 14. Upper head lobe width | 10.8 | 12.1 | 89 10.2–14.1 | 12.29±0.82 |

| 15. Lower head lobe width | 9.5 | 11.1 | 89 8.6–12.4 | 10.30±0.77 |

| 16. Predorsal length | 16.6 | 18.3 | 90 12.9–21.87 | 17.57±2.14 |

| 17. Postorbital length | 67.3 | 65.3 | 91 64.0–71.4 | 67.10±1.57 |

| 18. Snout length | 18.2 | 17.4 | 90 17.2–22.1 | 18.75±1.22 |

| 19. Upper jaw length | 20.1 | 20.5 | 90 17.2–22.8 | 20.28±1.21 |

| 20. Eye diameter | 11.7 | 11.3 | 92 9.7–12.6 | 11.43±0.64 |

| 21. Chin depth | 19.5 | 16.3 | 90 13.9–22.4 | 17.12±1.84 |

| 22. Lower opercular lobe | 29.2 | 27.6 | 88 21.8–32.7 | 26.68±2.26 |

| 23. Upper opercular lobe | 24.5 | 26.8 | 88 21.0–31.4 | 25.65±2.33 |

| 24. HW/HL | 1.13 | 1.15 | 91 1.05–1.28 | 1.12±0.05 |

| 25. Pupil/Eye diameter | 52.4 | 52.8 | 92 51.1–77.1 | 61.81±5.96 |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.