Mormyridae, Bonaparte, 1831

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1590/1982-0224-20180031 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3716511 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C3878D-FFFA-B31C-FCBB-F99825804F28 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Mormyridae |

| status |

|

Mormyridae View in CoL View at ENA .

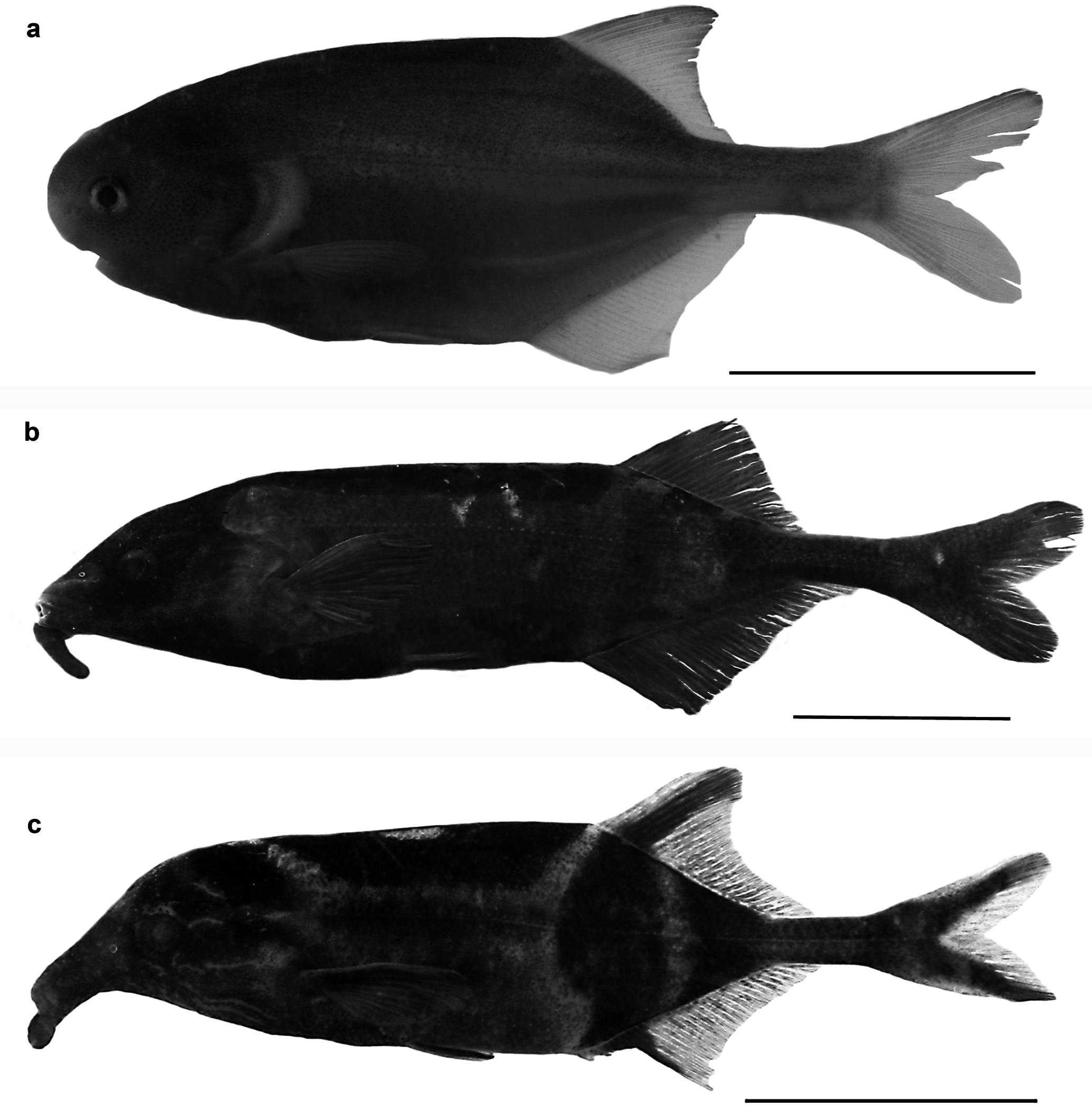

By far Mormyridae is the largest family of Osteoglossomorpha. It has about 21 genera and well over 200 species ( Fricke et al., 2018); the rate of new species descriptions in recent years suggests that there are far more to be discovered (e.g., a new genus, Cryptomyrus , was described recently from Gabon, suggesting that there are significant gaps in our knowledge of mormyrid diversity; Sullivan et al., 2016). All members of the family are found throughout Africa (except the Saharan, northern Maghreb, and southern Cape regions), and are particularly diverse in Central and West Africa ( Stiassny et al., 2007). The earliest fossil remains of the family, comprising fragmentary skull bones, teeth, and isolated vertebrae, are Middle Pliocene ( Greenwood, 1972), although the family is very poorly represented in the fossil record. Hilton (2003) noted the irony of this, as this family is the most species rich in the extant fauna, but most other families have a much more temporally and taxonomically extensive fossil record. The diversity of the family, established in part by fast evolution of reproductive isolation caused by selection in mate recognition signals (i.e., electric organ discharges), is pronounced and the family has been cited as the only example of a freshwater species flock in a riverine (vs. lacustrine) system ( Sullivan et al., 2002). All members of the family are weakly electric fishes, having both electroreceptors, and producing speciesspecific electric organ discharges for communication and localization purposes. There is great morphological diversity within this family in body form, but especially of their head shape, which ranges from blunt and rounded (e.g., Petrocephalus , Fig. 6a View Fig ; Pollimyrus ), to elongate, with a long snout and jaws (e.g., Gnathonemus and Campylomormyrus ; Figs. 6b,c View Fig ). The cranial diversity of certain taxa within the family, such as Campylomormyrus , has been suggested to reflect adaptive radiation driven by variation in diet ( Feulner et al., 2007). Mormyridae (inclusive of Gymnarchidae ; see below) all share an enlarged cerebellum, electric organs, electroreceptors, opercular bones covered by a thick fleshy flap, an intracranial diverticulum of the swim bladder, loss of the ventral hypohyal, absence of the basihyal and its toothplate, and features of the caudal skeleton ( Boulenger, 1898; Taverne, 1972, 1979; Hilton, 2003).

The systematics of Mormyridae has not been investigated recently from a morphological perspective (see Future Research Needs, below). The most taxonomically rich data set to be analyzed to date is that of Sullivan et al. (2000), who investigated relationships among representatives of 18 genera and 41 species using mitochondrial (12S and 16S rRNAs, Cytochrome b) and nuclear (RAG2) loci. The results of this analysis are largely congruent with those of Taverne (1972) at the higher taxonomical-levels, in that Gymnarchidae is its sister group, and the family can be divided into the Petrocephalinae (with only Petrocephalus ) and Mormyrinae (all other genera). Within Mormyrinae, Myomyrus macrops , and Mormyrops spp. were recovered as successive sister groups to all other members of the subfamily. Notable results also included the non-monophyly of Brienomyrus , Pollimyrus , Marcusenius , and Hippopotamyrus . Based on this topology, the authors conclude that electrocytes with penetrating stalks is a derived conditions but they evolved early in the evolution of Mormyrinae; the electrocytes of Gymnarchus are stalkless (hypothesized to be the larval form of electrocytes found in Mormyridae ) and those of Petrocephalus have non-penetrating stalks. There are several occurrences, presumably homoplastic, of reversal to the non-penetrating condition (e.g., within Brienomyrus , Paramormyrops , Marcusenius , and Campylomormyrus ), although the taxon sampling in these genera was insufficient to draw firm conclusions of the number of reversals within Mormyrinae. Other previous phylogenetic studies, reviewed by Sullivan et al. (2000), include Agnèse, Bigorne (1992), Van der Bank, Kramer (1996), Alves-Gomes, Hopkins (1997), Alves-Gomes (1999), and Lavoué et al. (2000). Recent molecular phylogenetic studies of relationships of Mormyrinae include those of Sullivan et al. (2016) and Levin, Golubtsov (2018), and provide further evidence that the taxonomy and phylogeny of Mormyridae is far from settled.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |