Hyemoschus aquaticus, Ogilby, 1841

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5721279 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5721317 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C587E3-1E7D-FF90-FA9A-F7A994F1F4AF |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Hyemoschus aquaticus |

| status |

|

Water Chevrotain

Hyemoschus aquaticus View in CoL

French: Chevrotain aquatique / German: Hirschferkel / Spanish: Ciervo ratén acuatico

Taxonomy. Moschus aquaticus Ogilby, 1841 ,

Bulham Creek , Sierra Leone .

The Water Chevrotain is thought to be the most ancestral of the extant tragulids, with its lineage separating from the species in Asia about 35 million years ago. Morphologically Hyemoschus shows many similarities with the Pliocene genus Dorcatherium of Africa and Europe, and both genera are quite distinct from the Asian Tragulus and Moschiola species. Geographic variation in Hyemoschus is poorly understood. Three subspecies have been named, but the validity of these names is questionable, and craniometrically these taxa are indistinguishable.

Subspecies and Distribution.

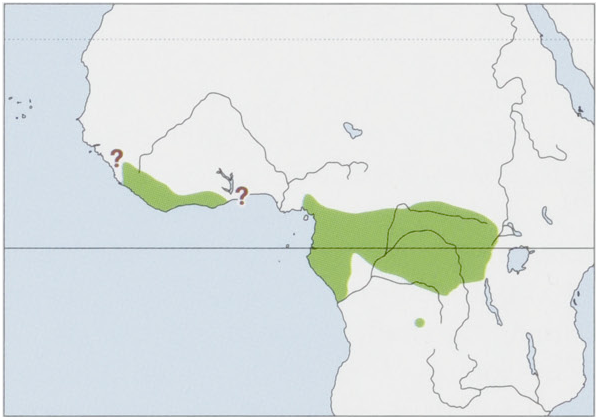

H.a.aquaticusOgilby,1841—WAfricafromGuineaandSierraLeonetoGhana.

H.a.bates:Lydekker,1906—Nigeria,Cameroon,andpresumablyneighboringcountries.

H. a. cottoni Lydekker, 1906 — Republic of the Congo, DR Congo, and presumably Uganda.

The Water Chevrotain reportedly has a disjunct distribution, occurring in coastal forests from West Africa and in the rainforests of Central Africa from Nigeria to DR Congo, marginally entering Uganda. It has been listed for the following countries in Central Africa: Angola ( Cabinda), Cameroon, Central African Republic, DR Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria, Republic of the Congo, and Uganda (Semliki Valley). A record from Angola’s Lunda Norte Province, near the Cassai River,is the southernmost record of the species. The species’ status in some countries remains unclear. It is apparently absent from the Republic of Benin and Togo (but the speciesis listed as probable in the Ot Basin in Togo); its supposed occurrence in Guinea Bissau and Senegal remains unsupported by evidence. The species was listed for Sierra Leone, although its presence had been called into question. Photographic evidence seems to clarify that the species occurs in Sierra Leone. In 1850, a specimen was recorded from Gambia, but the present status of the species is unclear. Local people report the species from the Boké Préfecture in NW Guinea, which might be the northernmost area from which the species has been recently reported. Extensive field and market surveys there and in the southern Guinea savanna belt did notfind evidence for the species’ presence. View Figure

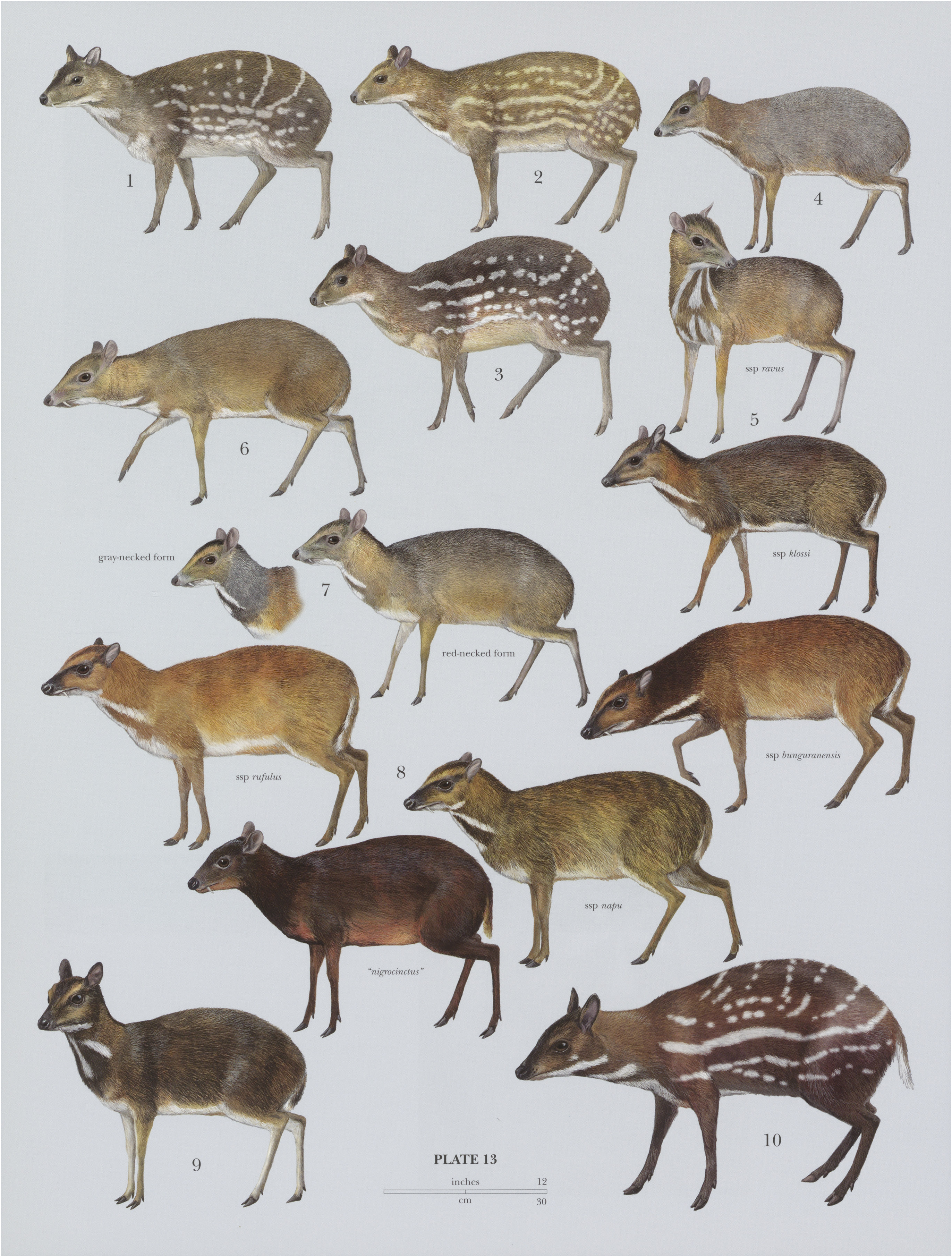

Descriptive notes. Head—body 60-102 cm, tail 7.2-10. 9 cm; weight 7-16 kg, with considerable regional variation in size. The Water Chevrotain has a stocky, rounded body and thin legs. Its hindquarters are powerfully muscled, and much higher than the shoulders, giving the body a sloped appearance. The neck is short and thick, and the small head is narrow and pointed, ending in a pointed, leathery nose with slit-like nostrils. The ears are rounded, but apparently quite long compared to other chevrotain species. Unusual for chevrotains and for ungulates in general, female Water Chevrotains are larger than males, weighing on average over 2 kg more than the males. The shorthaired coat is an overall rich chestnut brown color above and white on the undersides. The body is marked with horizontal white stripes running along the sides from the shoulder to the rump, with white spots on the back arranged in curved vertical rows. Such color patterns presumably provide camouflage during the day through their resemblance to dimpled sunlight on the dark forest undergrowth. There appears to be considerable variation in color and arrangement of the spots and lines, but it is unclear whether this variation allows for the consistent grouping of geographic variants. The chin, throat, and chest are white, covered in coarse hair, and broken up by bold transverse brown stripes that connect to the brown of the flanks. A dark brown lateral band separates the white of the throat stripes from the white of the chest. The tail is pale brown above and has fluffy white fur underneath. The legs are darkish brown. Neither sex has horns or antlers. However, as in other chevrotains, the upper canines are well developed and saber-like in males, flanking the mouth on either side of the lower jaw. Females also have enlarged canines, but they are shorter and blunter than in males. Male Water Chevrotains possess unique glands under the chin in the angle of the lower jaw. Like its Asian cousins, the Water Chevrotain is a good swimmer and can dive underwater or walk along the river bottom to elude predators. It can close its nostrils to keep water out. The species will rarely stray far from a water source, and it will retreat to water and jump in when threatened. When walking, the head is held low, allowing the Water Chevrotain to penetrate virtually impassable thickets and creating a nearly perfectly cone-shaped profile. The efficiency of this tunneling profile is enhanced by a shield of thick, reinforced skin on the dorsal surface, which protects the back from injuries inflicted by dense, resistant vegetation. This thick skin extends to the rump and throat.

Habitat. Like other chevrotains, Hyemoschus is confined to closed-canopy, moist tropical lowland forest, and within this habitat it concentrates in areas in the vicinity of streams and rivers. The species is, however, not a swamp specialist, and is often found in mature upland forest areas. Its range is thought to be limited by climatic factors: the species prefers habitats with very low seasonality and rainfall equal to or greater than 1500 mm /year, and it does not occur in areas that are even moderately seasonally arid. The species forages in clearings, floodplains, and along river banks at night, and retires to a hiding spot in dense cover during the day.

Food and Feeding. The Water Chevrotain is primarily a frugivore, and it has been suggested that year-round availability of fruits could be a key limiting habitat factor. Stomach content analysis of 19 animals in Gabon revealed that fruits comprise 68-7% of all foods eaten, which appears to be less than its Asian cousins. The rest of the diet includes leaves (9-9%), petioles and stems (20-5%), animal matter (0-14%), flowers (0-7%), and fungi (0-13%). Compared to duikers—small frugivores that share its habitat—the Water Chevrotain eats relatively little fruit and fungi, but many more succulent stems, and year-round fruit availability might not be as crucial a determinant for the species’ presence as suggested by a few ecological studies. At least 76 species of fruits have been identified in the species’ diet, with preferred species including Cylindropsis parvifolia (Apocynaceae) , Bombax buonopozense ( Bombacaceae ), Alchornea cordifolia (Euphorbiaceae) , Coelocaryon preussi and Pycnanthus angolensis (Myristicaceae) , and Cissus dinklager ( Vitaceae ). In addition to these fruits, figs (Ficus spp.), Pseudospondias fruits, palm nuts (Elaeis), and breadfruit (Treculia) are consumed, as well as the fruits of gingers and arrowroots. Most fruits consumed are small to medium-sized, with a diameter between 0-5 cm and 2 cm. Water Chevrotains also feed on insects; they actively hunt for ants by licking the ground along ant trails. Apparently crabs, carrion, and scavenged fish also feature in the species’ diet. The Water Chevrotain consumes significantly less animal matter and fungus during the dry season,as well as 44% fewer fruit species. Young individuals that are still nursing eat smaller amounts offruit than adults (only 48:4% of the diet) and a larger proportion ofleaves (31:3%).

Breeding. Due to the secretive nature of this species, little is known aboutits life cycle, and reports about breeding behavior often vary considerably. Olfactory communication is important in this species, and feces and urine are deposited anywhere. Both sexes announce their presence with these excrements, which are mixed with an excretion from the anal (male and female) and preputial (male) glands. The interramal gland is occasionally used for marking twigs. The Water Chevrotain also communicates through vocalizations, including an alarm bark. When fighting, females produce a high pulsing chatter. As with pigs, male Water Chevrotains typically vocalize through a closed mouth, when following a female in estrus. While being followed, a receptive female will stop at each cry, allowing the male to lick her rump. After several repetitions of this, the male mounts. An estrous female will mate with a male with whom she shares a home range. She gives birth to one, or occasionally two precocial fawns. Reported gestation lengths range from four to nine months, and it is unclear whether there are errors in these estimates or that indeed this wide range occurs under natural conditions. In Gabon, births occur throughout the year, although there is a peak in births in January and July-August, at the beginning of the twice-annual dry seasons. Infants are usually found separate from their mothers, “lying up” for the first three months of life. During this initial hiding period, the mother will visit her offspring periodically to suckle, at which time small infants are also washed using the tongue. Lactation lasts 3-6 months. The young disperse from the mother’s home range when they reach sexual maturity at 9-26 months of age. Maximum longevity is normally eight years of age, but the species has a potential lifespan of 11-13 years.

Activity patterns. The species is thought to be exclusively nocturnal in the wild, being active almost always between dusk and dawn. In a captive population in Monrovia Zoo, Liberia, activity patterns showed that the species was active 4% of the day and 67% of the night.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Water Chevrotain is mainly solitary. Male territories overlap those of females, but the males are rarely aggressive toward each other, unlike some of the Tragulus species from Asia, in which males frequently fight other males. Although Water Chevrotains do occasionally fight, using their tusks as weapons, they apparently prefer to avoid each other and keep to themselves. Fights are typically short in duration. Two competing males will rush at each other with their mouths open, poke at each other with their muzzles, and bite, using the canines in the upper jaw and incisors in the lower jaw. Females also fight but less frequently than males. Adult females occupy home ranges averaging 13-14 ha in size, and are typically accompanied by their latest offspring. Females usually remain in the same home range for life after they reach maturity. Males, on the other hand, are less sedentary, usually occupying an area for less than a year before moving on. The home ranges of males are typically larger than those of females, averaging 20-30 ha in size and overlapping with the home ranges of at least two females. In Gabon, recorded population densities were between 7-7 ind/km?® and 28 ind/km?, but in the Republic of the Congo, average densities appear to be lower, between 1-5 ind/km?® and 5 ind/ km?*. Whether such variation is due to ecological factors or caused by factors such as hunting is unclear. In West Africa, the species is apparently much rarer and densities presumably lower.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List, with the main threats being habitat loss, through agriculture and expanding human development, and hunting for bushmeat. Due to its secretive nature, there is little information on its status in individual countries within its extensive range, although there is some evidence that it is declining in specific areas. In the Niger Delta, the species was described originally as widespread in almost all freshwater habitats, but is now rare in all but the most remote areas, and rapidly becoming extinct in upland areas. The species is hunted for human consumption throughout its range. In Liberia, for example, the Water Chevrotain ranked second in a taste preference survey in eight urban communities. In south-west Cameroon, one animal fetches about US $ 6 in local markets, giving some idea of the commercial value of such species in places where most people earn less than US $ 1/day. In the central Ituri Forest, DR Congo, Water Chevrotains are regularly caught by net hunters, and consistently represent about 5% of the total catch, even in areas that have been hunted for years. Hunting appears to vary seasonally with the majority of animals entering markets in Equatorial Guinea at the start of the wet season.

Bibliography Ansell (1974), Barnett & Prangley (1997), Barnett et al. (1996), Barrie & Camara (2006), Blench (2007), Coe (1975), Crawford-Cabral & Verissimo (2005), Dubost (1975, 1978, 1979, 1984, 2001), Dubost & Feer (1992), East (1999), Gautier-Hion, Duplantier et al. (1985), Gautier-Hion, Emmons et al. (1980), Gray (1850), Happold (1973), Hart (1986), Hoyt (2004), Huffman (2010), Institute of Applied Ecology (1998), IUCN/ SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008), Juste et al. (1995), Kingdon (1997), Newing (2001), Nowak (1999), Pickford et al. (2004), Rahm & Christiaense (1966), Robin (1990), Sidney (1965), Steel (1994), Willcox & Nambu (2007).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Ruminantia |

|

InfraOrder |

Tragulina |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Hyemoschus aquaticus

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Moschus aquaticus

| Ogilby 1841 |