Hoplopholcus Kulczyński, 1908

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4726.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F0F95E18-9EFB-4169-B724-DAA71200413A |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03CB87CD-FFC4-FFA0-E9C0-FC957284FD87 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Hoplopholcus Kulczyński, 1908 |

| status |

|

Hoplopholcus Kulczyński, 1908 View in CoL View at ENA

Hoplopholcus Kulczyński, 1908: 63 View in CoL ; type species: Pholcus forskali Thorell, 1871 .

Hoplopholcus — Senglet 1971: 346 View in CoL . Brignoli 1979a: 352. Senglet 2001: 58.

Neartema Kratochvíl, 1940: 6 ; type species: Artema cretica Roewer, 1928 [= H. labyrinthi ( Kulczyński, 1903) View in CoL ]. Synonymized by Senglet (1971).

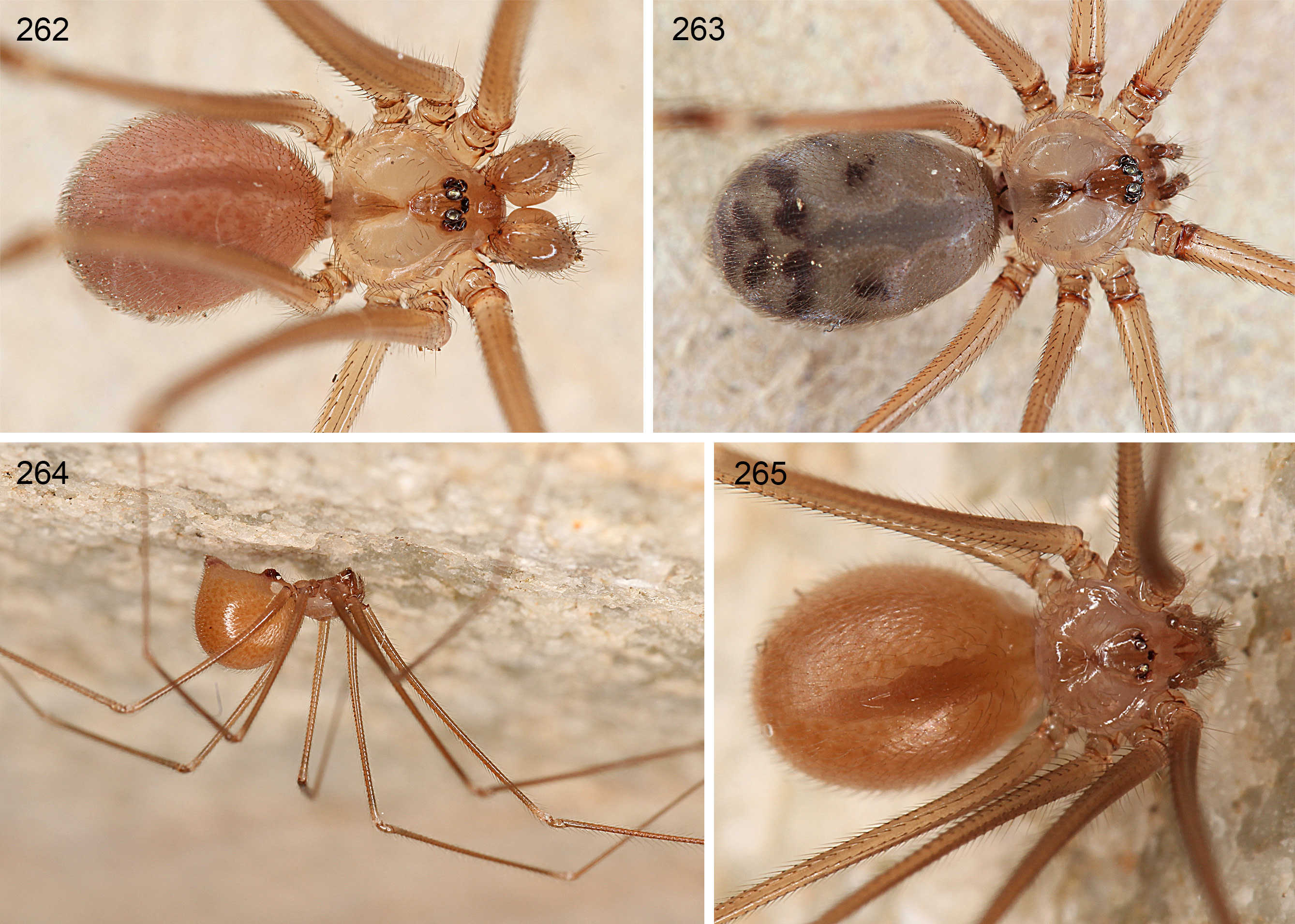

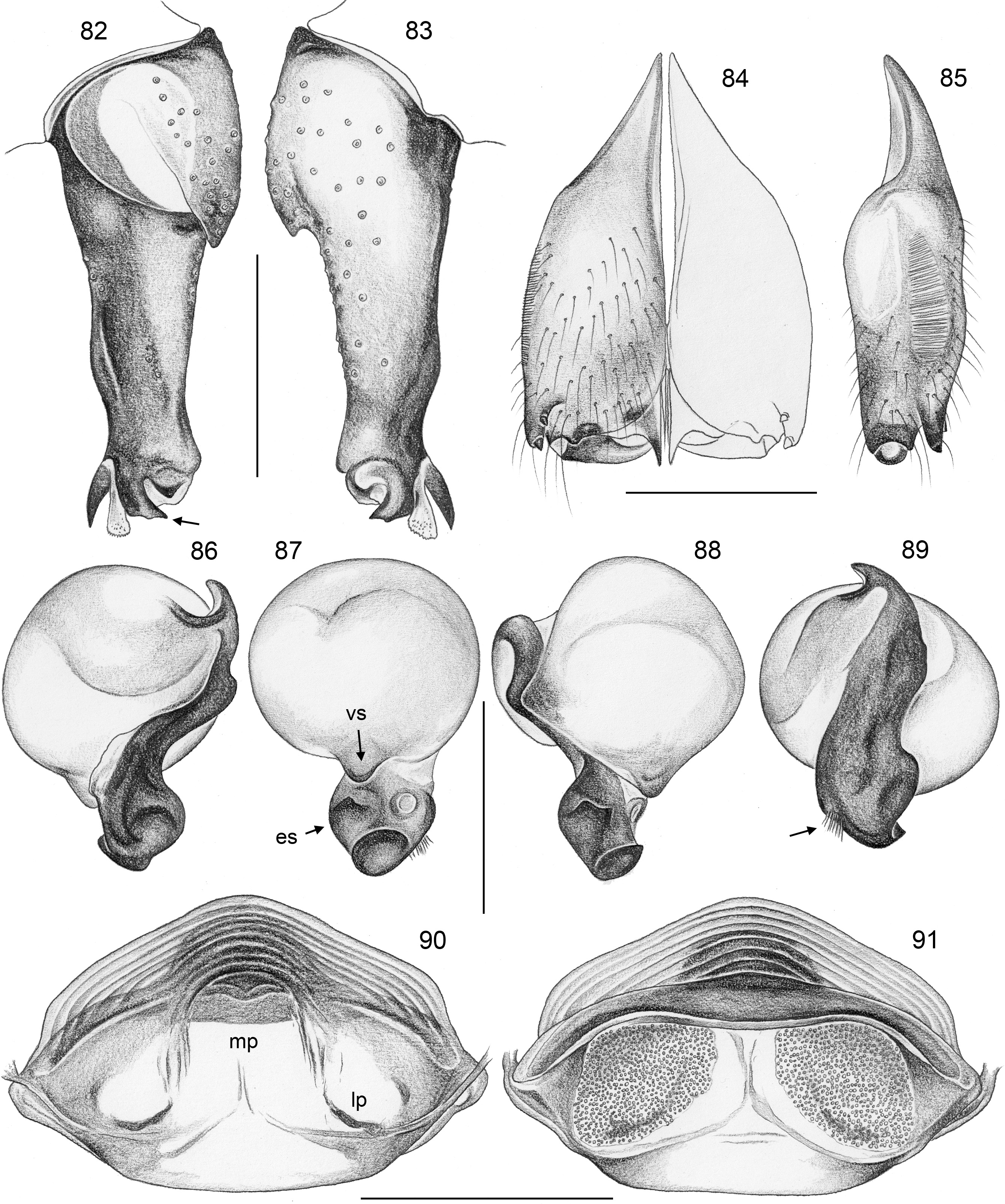

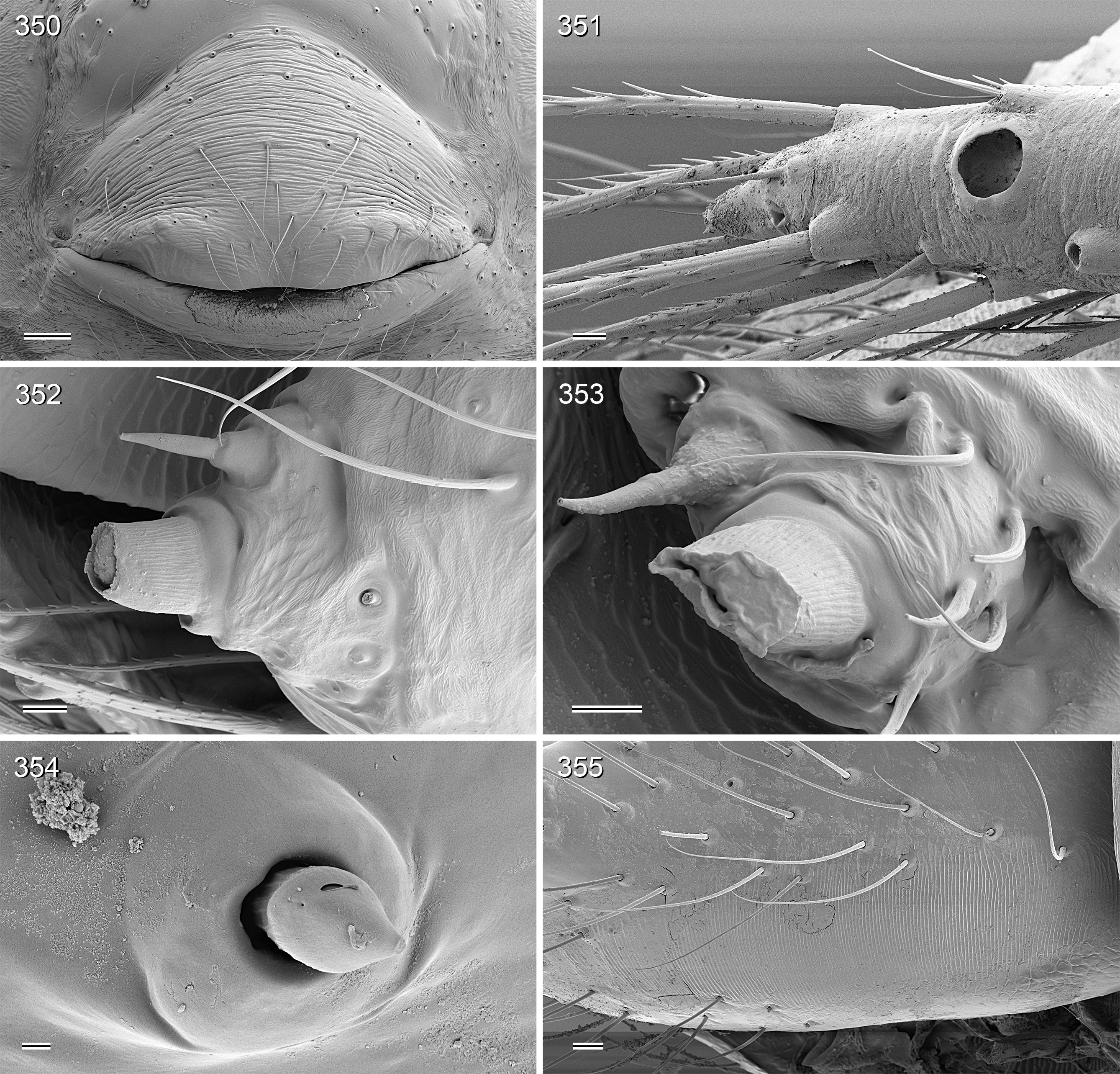

Diagnosis. Relatively large, long-legged pholcids (body length ~4–7; male leg 1 length ~30–60; leg 1 ~6– 10 x body length) with round to oval abdomen ( Figs 118, 119 View FIGURES 118–123 , 194 View FIGURES 194–199 , 264 View FIGURES 262–265 ). Distinguished from other Smeringopinae genera by the combination of: (1) male chelicerae with one pair of apophyses (e.g., Figs 23 View FIGURES 21–30 , 84 View FIGURES 82–91 ) set with 1–4 modified (cone-shaped) hairs each ( Figs 35 View FIGURES 31–36 , 108, 109 View FIGURES 106–111 , 228–231 View FIGURES 228–233 , 347 View FIGURES 344–349 ) ( Smeringopina with additional set of proximal lateral apophyses; Stygopholcus with many club-shaped hairs on frontal side); (2) chelicerae with stridulatory files ( Figs 33, 34 View FIGURES 31–36 , 64, 65 View FIGURES 64–69 , 233 View FIGURES 228–233 , 355 View FIGURES 350–355 ) (absent in Smeringopus and Smeringopina ); (3) male palpal tarsus without macrotrichia (e.g., Fig. 14 View FIGURES 12–20 ) (in contrast to Smeringopus ); (4) procursus tip with distinctive transparent process (e.g., Figs 1 View FIGURES 1–3 , 39 View FIGURES 37–42 , 234 View FIGURES 234–239 ) (otherwise present only in some undescribed North African taxa with unknown generic affinity; B.A. Huber, unpublished data); (5) legs without small dark longitudinal marks (e.g., Figs 6–11 View FIGURES 6–11 ) (in contrast to Holocnemus and Crossopriza ); (6) male anterior femora (femora 1 or femora 1–2) with single row of ventral spines ( Figs 45 View FIGURES 43–46 , 242, 243 View FIGURES 240–245 ) (spines absent in Smeringopina , Cenemus , and most species of Smeringopus ); (7) male gonopore with 4–8 epiandrous spigots ( Figs 36 View FIGURES 31–36 , 72 View FIGURES 70–75 , 107 View FIGURES 106–111 , 232 View FIGURES 228–233 , 291 View FIGURES 288–293 ) ( Smeringopus and Smeringopina with only two); (8) ALS with only two spigots each ( Figs 43, 44 View FIGURES 43–46 , 74, 75 View FIGURES 70–75 , 116 View FIGURES 112–117 , 224, 225 View FIGURES 222–227 , 292 View FIGURES 288–293 ) (seven to eight spigots in Smeringopus and Smeringopina ); (9) epigynum without external pockets (e.g., Figs 73 View FIGURES 70–75 , 350 View FIGURES 350–355 ) (in contrast to Cenemus , some species of Smeringopina and Smeringopus ); (10) abdomen posteriorly rounded (in lateral view), not pointed above spinnerets ( Figs 118, 119 View FIGURES 118–123 , 194 View FIGURES 194–199 , 264 View FIGURES 262–265 ) (pointed in many Holocnemus and Crossopriza ).

Description. Male. BODY. Total body length ~4–7; carapace width ~1.5–2.5. Carapace with deep central pit and pair of shallow furrows diverging from posterior side of pit toward posterior rim ( Figs 31, 32 View FIGURES 31–36 , 106 View FIGURES 106–111 , 222 View FIGURES 222–227 ); ocular area slightly raised, eye triads relatively close together (distance PME-PME usually ~0.8–1.3 x PME diameter, only in H. figulus and in some specimens of H. labyrinthi up to 2.0), each secondary eye accompanied by indistinct elevation ( Figs 222, 223 View FIGURES 222–227 , 344 View FIGURES 344–349 ; ‘pseudo-eyes’; cf. Huber 2009), AME large (usually ~40–60% of PME diameter, only in H. figulus smaller or absent). Clypeus high, never modified. Abdomen round to oval, not elevated or pointed above spinnerets ( Figs 118, 119 View FIGURES 118–123 , 194 View FIGURES 194–199 , 264 View FIGURES 262–265 ). Male gonopore with 4–8 epiandrous spigots ( Figs 36 View FIGURES 31–36 , 72 View FIGURES 70–75 , 107 View FIGURES 106–111 , 232 View FIGURES 228–233 , 291 View FIGURES 288–293 ), ALS with only two spigots each: one large widened spigot and one pointed spigot ( Figs 43, 44 View FIGURES 43–46 , 74, 75 View FIGURES 70–75 , 116 View FIGURES 112–117 , 224, 225 View FIGURES 222–227 , 292 View FIGURES 288–293 , 352, 353 View FIGURES 350–355 ); PMS with two spigots each, PLS without spigots (both apparently invariable in Pholcidae ; Huber 2000).

COLOR. In general ochre-yellow to brown, carapace usually with dark median band widened posteriorly and in ocular area (e.g., Figs 6, 7 View FIGURES 6–11 ); sternum usually dark brown, in a few species light ( H. cecconii , H. atik , H. konya , H. figulus ). Legs in most species with dark rings subdistally on femora and tibiae and in patella area, without dark rings in H. cecconii , H. atik , H. figulus , H. labyrinthi and H. minotaurinus . Abdomen in epigean species or populations with distinct dark pattern dorsally and laterally (e.g., Figs 10, 11 View FIGURES 6–11 , 195, 199 View FIGURES 194–199 ), and distinct ventral pattern, in cave-dwelling species or populations with dark marks often reduced to posterior part or without dark marks (e.g., Figs 6, 7 View FIGURES 6–11 , 122, 123 View FIGURES 118–123 , 262, 265 View FIGURES 262–265 ).

CHELICERAE. Chelicerae with stridulatory ridges ( Figs 33 View FIGURES 31–36 , 64 View FIGURES 64–69 , 290 View FIGURES 288–293 , 355 View FIGURES 350–355 ), with 1–4 modified (cone-shaped) hairs on each distal cheliceral apophysis (e.g., Figs 23 View FIGURES 21–30 , 84 View FIGURES 82–91 , 108, 109 View FIGURES 106–111 , 228–231 View FIGURES 228–233 , 347 View FIGURES 344–349 ).

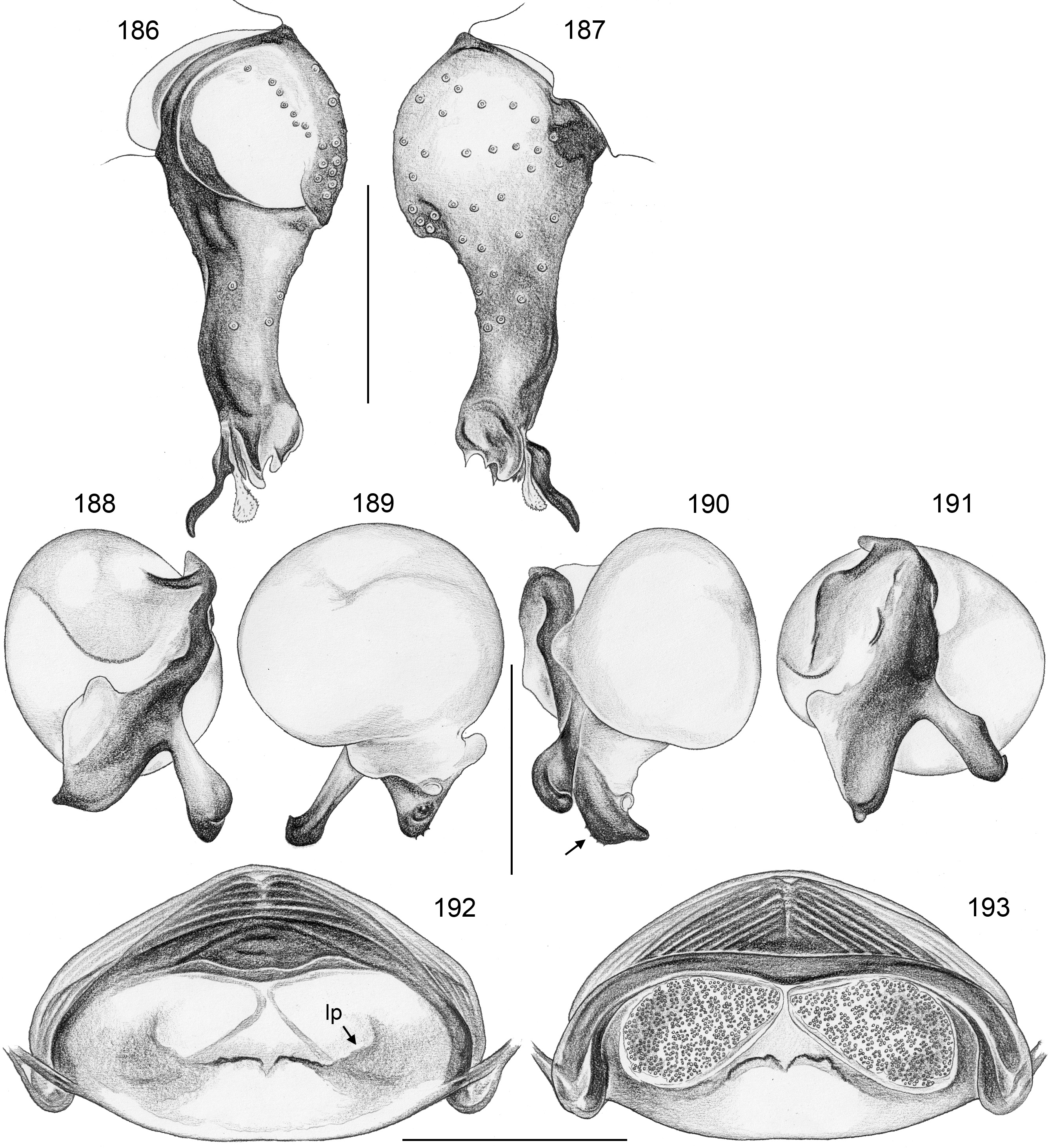

PALPS. Palpal coxa with variably distinct retrolateral hump; trochanter barely modified; femur widening distally, with variably distinct transversal dark line on retrolateral side (e.g., Figs 14 View FIGURES 12–20 , 49 View FIGURES 47–55 , 126 View FIGURES 124–129 ), with stridulatory pick (modified hair) proximally on prolateral side ( Figs 112 View FIGURES 112–117 , 354 View FIGURES 350–355 ); femur-patella joints shifted toward prolateral side (e.g., Fig. 12 View FIGURES 12–20 ); palpal tarsus without dorsal macrotrichia, palpal tarsal organ exposed ( Figs 37 View FIGURES 37–42 , 66 View FIGURES 64–69 , 111 View FIGURES 106–111 , 226 View FIGURES 222–227 ); procursus relatively simple and conservative ( Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1–3 ), with variably distinct ventral ‘knee’, distally always with ventral spine and transparent process, with variable set of additional sclerotized and membranous processes; genital bulb usually with two main sclerites ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1–3 ), one of them ventrally (‘ventral sclerite’), the other one carrying the sperm duct opening (‘embolar sclerite’, Figs 70 View FIGURES 70–75 , 240 View FIGURES 240–245 ) and sometimes provided with hair-like or small cone-shaped processes (e.g., Figs 41 View FIGURES 37–42 , 240 View FIGURES 240–245 ); with variably distinct dorsal membranous process and sometimes with sclerotized prolateral process.

LEGS. Legs long and relatively thin, leg 1 length ~20–80, tibia 1 length 6–20 (usually ~8–16), tibia 2 always longer than tibia 4 (~1.1–1.2 x). Tibia 1 L/d usually ~40–70, lowest values in epigean species, highest values in cave-dwelling species/populations. Femur 1 slightly stronger than other femora. Spines always present on femur 1 ( Figs 45 View FIGURES 43–46 , 117 View FIGURES 112–117 , 242, 243 View FIGURES 240–245 , 349 View FIGURES 344–349 ), usually ~ 15–35 in single ventral row, proximally gradually transforming into regular setae; spines in some species also present on femur 2, very rarely also on tibia 1; some species with curved hairs ( Fig. 46 View FIGURES 43–46 ) on anterior tibiae and metatarsi (1–2 or 1–3), others without curved hairs; retrolateral trichobothrium in proximal position (at 4.0–7.5% of tibia length in tibia 1), prolateral trichobothrium usually present on all tibiae, in some species absent on tibia 1 ( H. labyrinthi , H. minotaurinus , H. suluin , H. figulus ); metatarsus with one dorsal trichobothrium (apparently invariable in Pholcidae ; Huber 2000). Tarsal pseudosegments very indistinct, never regular rings but rather indistinct irregular platelets ( Fig. 244 View FIGURES 240–245 ). Tarsus 4 with two rows of prolatero-ventral combhairs (cf. fig. 13 in Huber & Fleckenstein 2008). Tarsal organs of legs capsulate ( Fig. 114 View FIGURES 112–117 ).

Female. Female in general very similar to male, chelicerae also with stridulatory ridges ( Figs 34 View FIGURES 31–36 , 65 View FIGURES 64–69 , 233 View FIGURES 228–233 ) but otherwise unmodified; legs slightly shorter than in male, also with curved hairs (if present in male), but without spines. All tarsal organs capsulate (i.e., also on palps; Figs 38 View FIGURES 37–42 , 115 View FIGURES 112–117 , 227 View FIGURES 222–227 , 241 View FIGURES 240–245 , 351 View FIGURES 350–355 ).

FEMALE GENITALIA. Epigynum usually consisting of large, simple anterior plate and short but wide posteri- or plate (e.g., Figs 15 View FIGURES 12–20 , 50 View FIGURES 47–55 , 350 View FIGURES 350–355 ); usually with distinct pair of bulging areas in front of anterior plate. Internal genitalia ( Fig. 3 View FIGURES 1–3 ) with sclerotized arc that consists of dorsal and ventral parts and is usually visible in uncleared specimens; uterus externus usually with ventral median pouch sometimes large and distinct (e.g., Figs 62 View FIGURES 56–63 , 286 View FIGURES 278–287 ), sometimes small and/or indistinct (e.g., Figs 104 View FIGURES 98–105 , 342 View FIGURES 334–343 , 408 View FIGURES 400–409 ), and pair of lateral pouches/ridges sometimes connected to median pouch (e.g., Figs 29 View FIGURES 21–30 , 62 View FIGURES 56–63 ), sometimes connected to ventral arc (e.g., Figs 286 View FIGURES 278–287 , 342 View FIGURES 334–343 , 386 View FIGURES 378–387 ), sometimes not connected to other sclerotized elements (e.g., Figs 104 View FIGURES 98–105 , 166 View FIGURES 158–167 ); rarely with additional set of lateral sclerites connected to ventral arc (arrow in Fig. 260 View FIGURES 252–261 ); pore plates usually large, with homogeneously distributed pores (e.g., Figs 30 View FIGURES 21–30 , 63 View FIGURES 56–63 ).

Monophyly. The morphological cladistic analysis of Smeringopinae in Huber (2012) included only two representatives of Hoplopholcus . It identified two synapomorphies for the genus: the presence of curved hairs on legs, and the ‘membranous process’ (here called ‘transparent process’) of the procursus. The first character is highly homoplastic and may or may not be a valid synapomorphy. The second appears indeed unique, but a very similar structure occurs in a group of undescribed Smeringopinae from Northern Africa (B.A. Huber, unpublished data). The recent molecular phylogeny of Pholcidae ( Eberle et al. 2018) included 12 species of Hoplopholcus and the monophyly of the genus was recovered with maximum support. The cladogram in Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 is extracted from Eberle et al. (2018), with names updated and taxa slightly rearranged.

Generic relationships. Both the morphological ( Huber 2012) and the molecular analyses ( Eberle et al. 2018) placed Hoplopholcus in a “northern clade” of Smeringopinae ( Huber et al. 2018) , closer to the genera Crossopriza , Stygopholcus , and Holocnemus , than to the Sub-Saharan genera Smeringopus and Smeringopina . The relationships among genera within the northern clade remain unclear. Morphological data favored a sister-group relationship between Hoplopholcus and Stygopholcus , while molecular data placed Hoplopholcus as sister to all other genera of the northern clade ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ) (but note that Cenemus was not included in the molecular analysis).

Specific relationships. Molecular data have identified a few species groups that appear also supported by morphological characters. Beyond that, relationships among species remain largely unresolved. The two cave-dwelling species on Crete ( H. labyrinthi , H. minotaurinus ) are likely sister species; they share the unique thin membranous process distally on the procursus (arrows in Figs 22 View FIGURES 21–30 , 57 View FIGURES 56–63 ) and the prolateral process between ventral bulbal sclerite and embolar sclerite (arrows in Figs 26 View FIGURES 21–30 , 59 View FIGURES 56–63 ). Together with H. suluin they also share hair-like processes on the embolar sclerite ( Figs 41 View FIGURES 37–42 , 71 View FIGURES 70–75 , 89 View FIGURES 82–91 ). Together with H. figulus (not included in the molecular analysis) these three species share the absence of the prolateral trichobothrium on tibia 1.

A second species group identified by molecular data includes several species from southern Turkey ( H. asiaeminoris to H. dim in Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ) and the more widespread H. minous . All these species share a slender ventral sclerite of the genital bulb ( Figs 101 View FIGURES 98–105 , 147 View FIGURES 142–151 , 163 View FIGURES 158–167 , 189 View FIGURES 186–193 ). The inclusion of H. “Tur21” in this group leads to the prediction that the unknown male of this species also shares this morphological character.

Finally, the sister-group relationship between the type species H. forskali and H. konya suggested by molecular data is neither supported nor contradicted by morphological data.

Natural history. The large majority of records are from caves. However, most cave-dwelling species occupy the twilight area and do not occur in deeper parts of the caves. Some of these cave-dwelling species have also been found under large rocks or in deeper layers of rock fields (e.g., H. labyrinthi , H. longipes , H. patrizii ), suggesting that they are actually not strictly cave-dwelling but just depend on certain conditions that are shared by caves near the entrance and by shallow subterranean habitats (cf. Huber 2018). As a result, most cave-dwelling Hoplopholcus are only slightly troglomorphic, with more slender legs and paler coloration but with fully developed eyes. The only exception regarding eye development is H. figulus , but even this most troglomorphic representative of the genus has been found under rocks in a forest. The formally undescribed H. “Tur21” was found deep within Gilindere cave only, far from the entrance, but is also only slightly troglomorphic.

A few species are clearly epigean, and are commonly found among rocks in forests, in particular H. minous and H. forskali . The latter species is the only one that has spread far north into eastern Central Europe where it is an anthropophilic species, occupying both natural habitats and neglected and abandoned human constructions (rather than inhabited and heated rooms that are occupied by Pholcus phalangioides ; Kovács & Szinetár 2016).

Some species (e.g., H. minotaurinus , H. cecconii ) seem to include hypogean and epigean populations with significant differences in leg length (see redescriptions below).

As usual in Pholcidae , Hoplopholcus species usually vibrate their bodies when disturbed. Another common reaction to disturbance is retreating toward the back into holes and crevices or (rarely) dropping out of the web.

Most or all species of Hoplopholcus build the ‘typical’ pholcid dome-shaped webs with a tangle of lines above the sheet. Silk balls that are facultatively attached to the webs and that may be a synapomorphy of Smeringopinae ( Huber 2012) have never been observed in Hoplopholcus .

Males and females were often found to share a web. Females carry their round egg-sacs ( Figs 11 View FIGURES 6–11 , 119, 123 View FIGURES 118–123 , 197 View FIGURES 194–199 ) until the spiderlings hatch and even a short while after that. Some data on mating biology and genital mechanics exist for H. forskali and H. minotaurinus (see individual Natural history sections below).

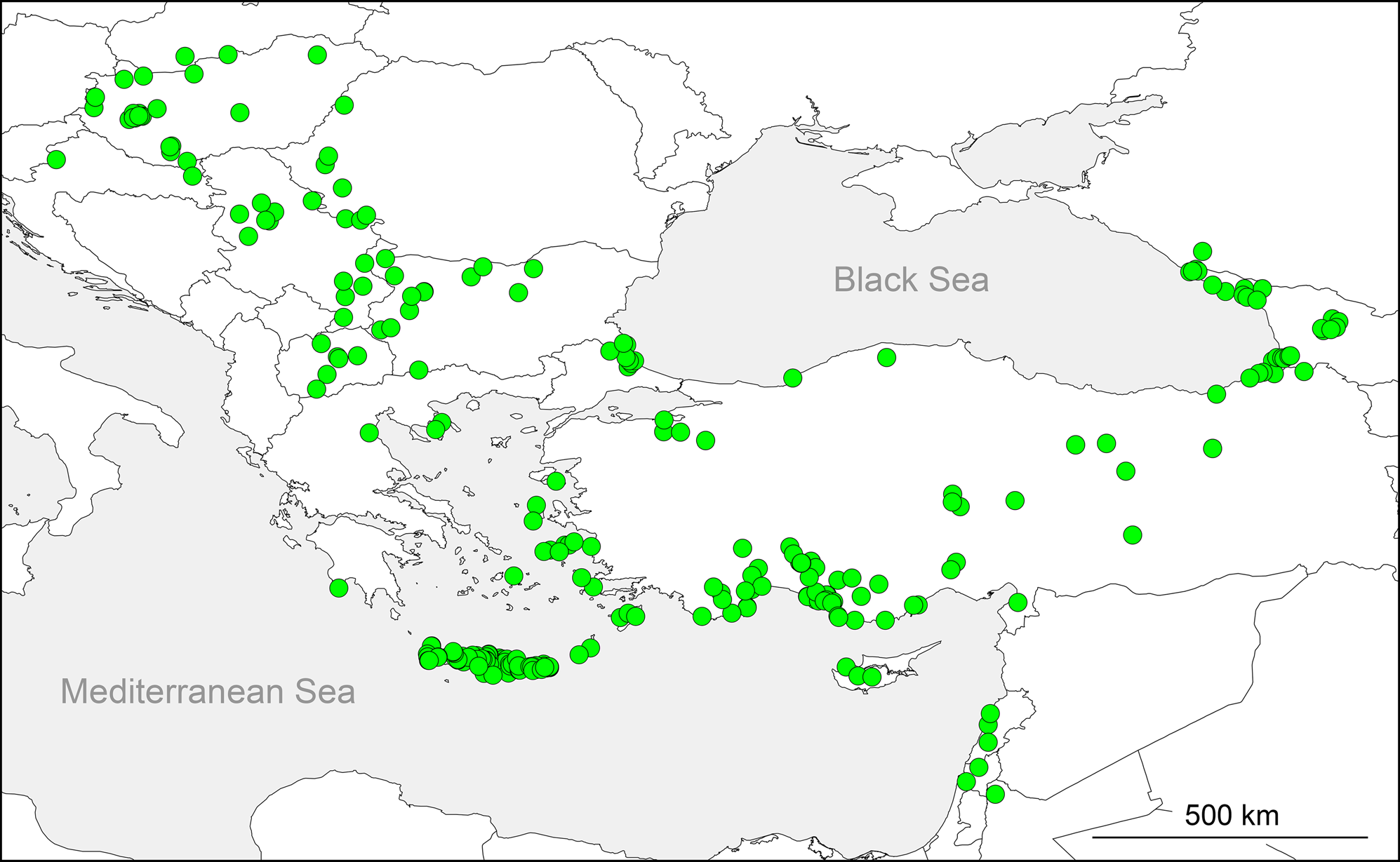

Distribution. Turkey and Greece are clearly the centers of distribution in the sense that the majority of species is largely or entirely restricted to Turkey and Greece, in particular southern Turkey and Crete. Three widespread species extend the distribution of the genus toward eastern Central Europe ( H. forskali ), toward the area around the eastern Black Sea ( H. longipes ), and toward the Levante ( H. cecconii ) ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Previous records from the Adriatic Coast, Iraq, and Turkmenistan are very probably based on misidentifications (see Distribution section in the redescription of H. forskali ).

At several localities, two species have been found close to each other. Usually this was an epigean and a hypogean species (e.g., H. minous and H. figulus on Samos, or H. minous and H. minotaurinus at Exo Mouliana), but it seems that two species do never share a cave. This is particularly noteworthy in Crete, where H. labyrinthi and H. minotaurinus have previously been reported to share caves. Reexaminations of the relevant specimens showed that all apparent cases of shared caves were based on misidentifications (see redescriptions of these two species below).

Composition. Hoplopholcus now includes 16 described species, all of which are treated below. The collections seen include a few further possible species that are not formally described, either because males are not known or because few specimens are available, partly of uncertain status. It does not seem that Hoplopholcus is much more diverse than currently known, but further species are most likely to be found in Turkey, in particular in caves.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Hoplopholcus Kulczyński, 1908

| Huber, Bernhard A. 2020 |

Hoplopholcus — Senglet 1971: 346

| Senglet, A. 2001: 58 |

| Brignoli, P. M. 1979: 352 |

| Senglet, A. 1971: 346 |

Neartema Kratochvíl, 1940: 6

| Kratochvil, J. 1940: 6 |

Hoplopholcus Kulczyński, 1908: 63

| Kulczynski, M. V. 1908: 63 |