Echinolittorina interrupta

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2184.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D3606F-A53B-FFA3-FF26-FAF6FAA4FE52 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Echinolittorina interrupta |

| status |

|

Echinolittorina interrupta View in CoL (C.B. Adams in Philippi, 1847)

( Figures 2D View FIGURE 2 , 16C, D View FIGURE 16 , 22–24 View FIGURE 22 View FIGURE 23 View FIGURE 24 )

? Trochus ziczac [var.] β Gmelin, 1791: 3587 (refers to Chemnitz 1781, pl. 166, fig. 1600a, b; Zuckerinsuln [West Indies]).

Phasianella lineata Lamarck, 1822: 54 (no locality; in part; lectotype ( Bequaert 1943) is specimen figured by Delessert (1841: pl. 37, fig. 11 a, b), MHNG 1096/87/1, photograph seen, this is Littoraria tessellata (Philippi, 1847) View in CoL ; 3 paralectotypes are E. interrupta View in CoL , fide Bandel & Kadolsky (1982), MHNG 1096/87/2–4, photograph of 1096/87/2 seen).

Litorina lineata —Philippi, 1847: 163–164, Litorina View in CoL pl. 3, fig. 18 (in part, includes E. angustior , E. jamaicensis View in CoL ; not Lamarck, 1822 = Littoraria tessellata View in CoL ). Küster, 1856: 23–24, pl. 3, figs 12–15 (not Lamarck, 1822).

Littorina (Melarhaphe) lineata View in CoL —von Martens, 1900: 583 (in part, includes E. angustior , E. jamaicensis View in CoL ; not Lamarck, 1822).

Littorina lineata View in CoL — Borkowski, 1975: 369–377 (in part, includes E. angustior , E. lineolata View in CoL ; not Lamarck, 1822).

Littorina ziczac View in CoL — Deshayes, 1843: 243–244 (in part, includes E. ziczac View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791). Bequaert, 1943: 14–18 (in part, includes E. lineolata View in CoL , E. ziczac View in CoL , E. jamaicensis View in CoL , E. angustior , E. placida View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791).

Litorina ziczac View in CoL — Weinkauff, 1878: 32 (in part, includes E. ziczac View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791). Weinkauff, 1883: 220 (in part, includes E. angustior , E. jamaicensis View in CoL , E. ziczac View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791).

Littorina (Melarhaphe) ziczac View in CoL — Tryon, 1887: 251 (in part, includes E. angustior , E. jamaicensis View in CoL , E. lineolata View in CoL , E. ziczac View in CoL , Littoraria glabrata View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791; as Melaraphe View in CoL ).

Litorina ziczac var. interrupta C.B. Adams View in CoL in Philippi, 1847: 164 (in synonymy of Litorina lineata ; made available by Küster, 1856; neotype (here designated) MCZ 186123, Fig. 22A View FIGURE 22 herein; Jamaica).

Nodilittorina (Nodilittorina) interrupta — Bandel & Kadolsky, 1982: 23–25, figs 5 (shell, egg capsule, operculum, radula), 7 (map), 16 (larval shell), 17 (embryonic shell), 23–26 (shells and radulae).

Littorina interrupta View in CoL — De Jong & Coomans, 1988: 19. Díaz & Puyana, 1994: 124–125, pl. 34, fig. 402.

Nodilittorina interrupta View in CoL — Britton & Morton, 1989: 86, fig. 4- 5N. Reid, 2002a: 259–281.

Nodilittorina (Echinolittorina) interrupta View in CoL — Reid, 1989: 99. Taylor & Reid, 1990: 208 (shell microstructure).

Echinolittorina interrupta View in CoL — Williams, Reid & Littlewood, 2003: 60–86. Williams & Reid, 2004: 2227–2251, fig. 6E (map) (in part, includes E. placida View in CoL ).

Littorina (Melarhaphe) floccosa Beck View in CoL in Mörch, 1876: 138 ( St Thomas [Lesser Antilles]; lectotype ( Bandel & Kadolsky 1982) ZMK; in part, ‘var. Α’ is E. jamaicensis View in CoL ; as Melaraphe View in CoL ).

Littorina (Melarhaphe) philippii var. latistrigata von Martens, 1900: 577 View in CoL , 585–586, pl. 43, fig. 18 (Punta Arenas, W Costa Rica [in error; Reid 2002b: 88]; 2 syntypes ZMB, seen).

Littorina lineolata View in CoL —Kaufman & Götting, 1970: 349, fig. 35 (not d’Orbigny, 1840). Flores, 1973a: 15–16, pl. 2, figs 11–15 (in part, includes E. lineolata View in CoL , E. jamaicensis View in CoL ; not d’Orbigny, 1840).

Littorina sp. Bandel, 1974a: 98 , 103, 107, figs 9 (shell), 16A and 17 (egg capsule), 18–22 and 46–47 (radula). Bandel, 1975: 15–16, pl. 1, figs 4–6 (larval shell).

Littorina angustior View in CoL — Díaz & Puyana, 1994: 124, pl. 34, fig. 401 (in part, includes E. angustior View in CoL ; not Mörch, 1876).

Taxonomic history: In his discussion of ‘ Litorina lineata d’Orbigny’ (this attribution is incorrect, see Taxonomic History of E. angustior View in CoL ), Philippi (1847) was the first to mention the name Litorina ziczac var. interrupta View in CoL , given by C.B. Adams to a small form with a distinct black spiral band, but which Philippi did not consider to be worth varietal status. He did not explicitly figure this form, although one of the two shells illustrated in his figure 18 resembles it. The name was therefore effectively published in the synonymy of Litorina lineata . Subsequently, there was a mention and figure of Adams’ Litorina ziczac var. interrupta View in CoL by Küster (1856), again in the discussion of ‘ Litorina lineata d’Orbigny’ (and therefore arguably in synonymy). In their revision of the western Atlantic littorinids, Bandel & Kadolsky (1982) considered that the name had been “accepted for a taxon” by Küster, thereby making it available (ICZN, 1999: Art. 11.6) and they therefore adopted the name as valid. This interpretation of Küster’s usage is questionable, but it is not desirable to replace this now familiar name. Clench & Turner (1950) considered Küster’s figure (which they credited to Philippi) to be the lectotype, and themselves figured a specimen from the C.B. Adams collection (MCZ 186123) as a ‘paratype’. Bandel & Kadolsky (1982) argued that only material available to Philippi (1847) had type status, and so did not select a type from the material of C.B. Adams in MCZ, although they figured the same specimen as had Clench & Turner (1950). In view of the confusion surrounding the black-and-white littorinids of the western Atlantic, it is desirable that the name ‘ interrupta View in CoL ’ should be represented by a type specimen. No material associated with Philippi is available, and therefore this same figured specimen is here designated as neotype.

Mörch (1876) listed this species under the manuscript name L. floccosa Beck , and included ‘ L. ziczac var. fasciata interrupta C.B. Adams teste Phil.’ in the synonymy. He also mentioned a ‘var. Α sulcis profundioribus’ and listed ‘ L. glaucocincta Beck mss’ after it. From the format of the entire work it is clear that this last is intended as a synonym, not as a name for valid usage; nevertheless, Bandel & Kadolsky (1982) identified a ‘holotype’ in MZK and this is the species E. jamaicensis .

As first noted by Deshayes (1843), the type material of Phasianella lineata Lamarck, 1822 consists of a mixture of two species, now classified as Littoraria tessellata and E. interrupta respectively. The specimen figured by Delessert (1841) was the former, and was designated as lectotype by Bequaert (1943), thereby fixing the concept of Lamarck’s specific name. In fact Littoraria lineata ( Lamarck, 1822) appears to be the valid name of Littoraria tessellata , and Littorina lineata was used in that sense by Mörch (1876). [As noted by Bequaert (1943), Abbott (1964) and Bandel & Kadolsky (1982), Littoraria lineata is a secondary homonym of Buccinum lineatum Gmelin, 1791 , which is a synonym of Littoraria scabra ( Linnaeus, 1758) ; however, Gmelin’s name is also a primary homonym of Buccinum lineatum da Costa, 1778, removing the secondary homonymy.]

Nineteenth century authors invariably included this species under the specific names ziczac or lineata , giving it at most the status of a colour variety, distinguished by its spiral black band ( Gmelin 1791; Philippi 1847). It was first recognized as a distinct species in Colombia by Bandel (1974a) from its shell and egg capsules, although it was not identified. Borkowski (1975) considered that the Colombian species fell within the range of variation of ‘ L. lineata ’ (i.e. E. angustior ), but Bandel & Kadolsky (1982) restored the name interrupta , as described above. Reid (1989, 2002a; Williams & Reid 2004) included specimens from the Gulf of Mexico in the concept of E. interrupta , but these are here distinguished as a separate species, E. placida .

Diagnosis: Shell medium size; whorls only slightly rounded; 8–10 primary spiral grooves; few secondary grooves; grooves weak on last whorl; dark oblique axial lines, broad black spiral band above suture on spire, band often persisting on last whorl. Penis with tapering filament thickened and glandular at base, glandular disc only slightly projecting. Continental shores of Caribbean Sea, Greater and Lesser Antilles. COI: GenBank AJ623011 View Materials , AJ623012 View Materials .

Material examined: 70 lots (including 15 penes, 5 sperm samples, 3 pallial oviducts, 2 radulae).

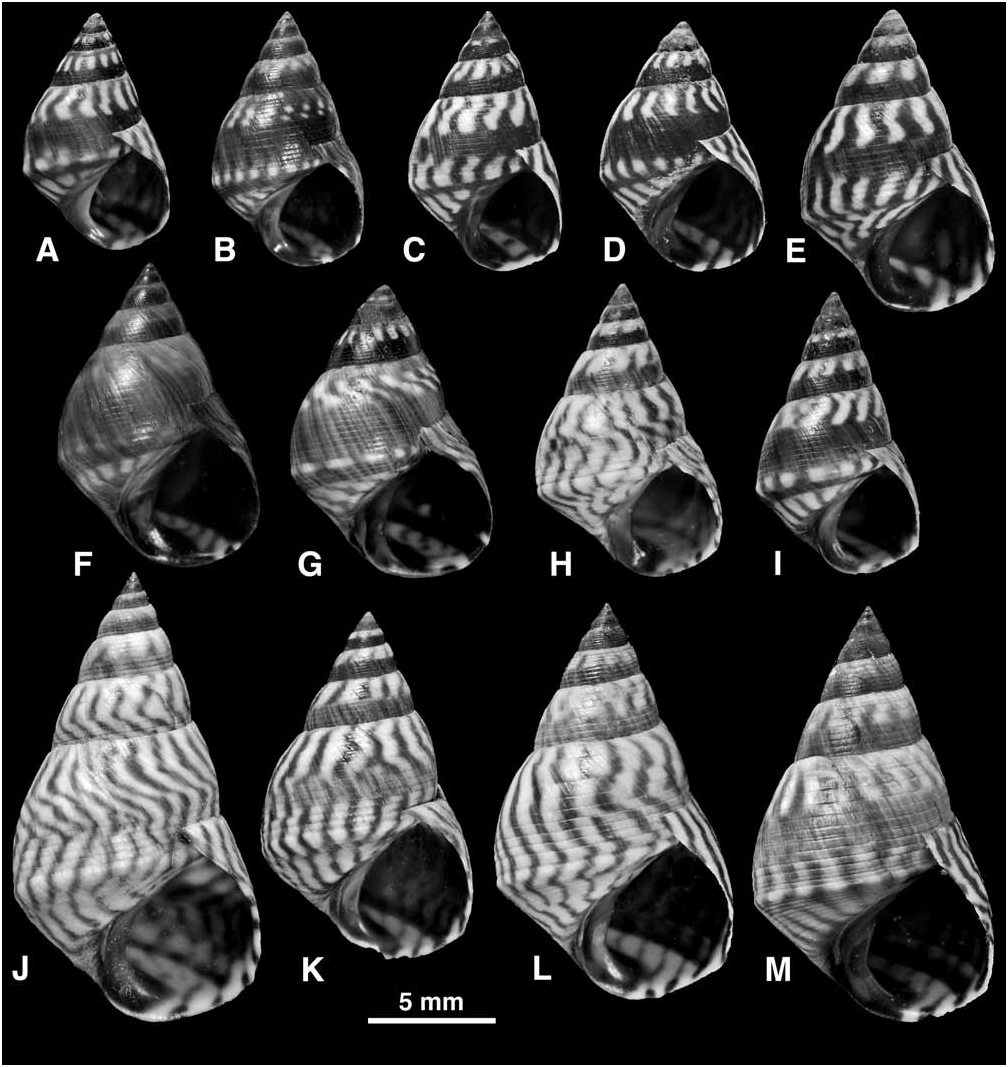

Shell ( Fig. 22 View FIGURE 22 ): Mature shell height 7.8–19.4 mm. Shape slightly succineiform, high turbinate or tall (H/B = 1.45–1.81, SH = 1.50–2.15); spire whorls flattened or slightly rounded; suture distinct; spire profile straight to slightly convex; periphery of last whorl angled. Columella short, slightly hollowed and pinched at base; eroded parietal area small or absent. Sculpture of 8–10 primary spiral grooves on spire whorls; a few secondary grooves appear (by division or interpolation) near periphery and on base of last whorl, giving 12–18 incised lines above and 9–16 below periphery; sculpture always fine, may become obsolete on shoulder or most of last whorl; peripheral rib 2–3 times width of adjacent ribs; spiral microstriae weak or absent. Protoconch 0.26 mm diameter, 2.5 whorls. Ground colour white with narrow oblique undulating or zigzag brown to black lines; broad black band on lower half of spire whorls, band may be distinct, pale or absent on last whorl; darkest shells entirely blackish brown with 3 rows of white spots at suture, periphery and on base, or only basal row; aperture dark brown with pale band at base and at shoulder; columella purple brown.

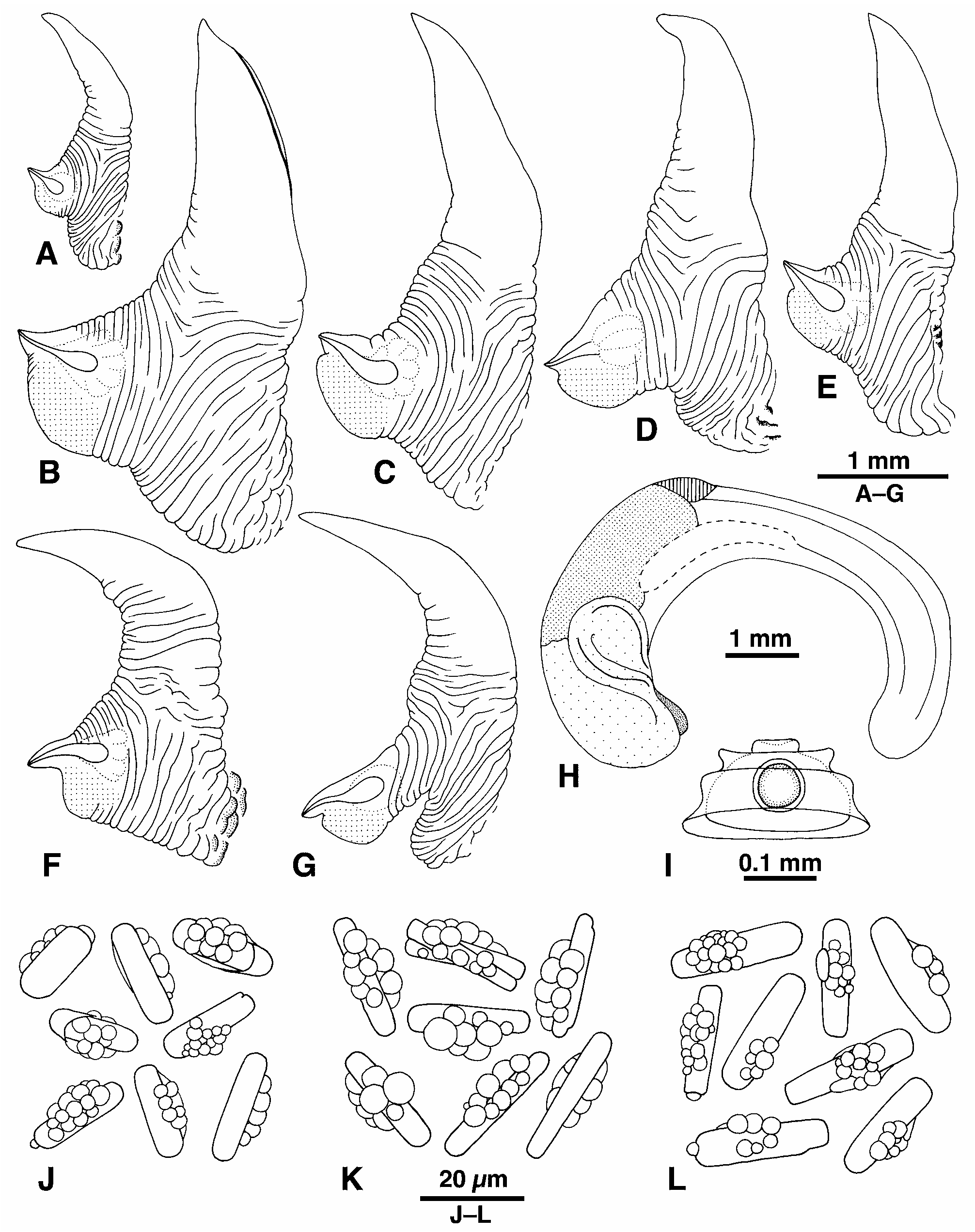

Animal: Head black, no unpigmented stripe across snout; tentacle pale around eye, with two broad longitudinal black stripes (occasionally fused) and black tip; sides of foot black. Operculum ( Fig. 2D View FIGURE 2 ): opercular ratio 0.38–0.41. Penis ( Fig. 23A–G View FIGURE 23 ): filament with small opaque glandular thickening at base, gradually tapering to pointed tip, 0.5–0.6 total length of penis, sperm groove ends terminally; mamilliform gland approximately same size as penial glandular disc, borne together on short projection of base, glandular disc projecting only slightly; penis unpigmented or slightly pigmented at base. Euspermatozoa 70–80 µm; paraspermatozoa ( Fig. 23J–L View FIGURE 23 ) containing single parallel-sided rod-piece with rounded ends, 16–27 µm, usually projecting from cell, which is packed with large round granules. Pallial oviduct ( Fig. 23H View FIGURE 23 ): copulatory bursa separates at half to two-thirds of length of straight section from anterior end and extends back to albumen gland. Spawn ( Fig. 23I View FIGURE 23 ): an asymmetrically biconvex pelagic capsule 200 µm diameter, with broad peripheral rim overhanging base, dome-shaped upper side sculptured by 3 concentric rings, containing single ovum 50 µm diameter ( Bandel 1974a: Colombia).

Radula ( Fig. 16C, D View FIGURE 16 ): Relative radula length 3.77–7.83. Rachidian: length/width 1.48–1.60; tip of major cusp pointed. Lateral and inner marginal: 4 cusps, tip of major cusp rounded. Outer marginal: (6)7–8 cusps.

Range ( Fig. 24 View FIGURE 24 ): Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Lesser Antilles, continental coastline of Caribbean Sea. Range limits: 5 km S Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico ( BMNH); Punta Gorda, Belize ( BMNH 20081002); Livingston, Guatemala ( BMNH); Roatan I., Honduras ( BMNH 1961730); Monkey Point, Nicaragua ( USNM 125436); Golfe de Uraba, Colombia ( IRSNB); Bahia Honda, Colombia ( IRSNB); Aruba, Netherlands Antilles ( USNM 835622); Isla Margarita, Venezuela ( ZMA); Chacachacare I., Trinidad ( BMNH); Silver Sands, Christ Church, Barbados ( BMNH); English Harbour, Antigua ( USNM 862272); Brewer’s Bay, St Thomas ( BMNH); El Desecheo I., Mayaguez Bay, Puerto Rico ( USNM 464280); Sanchez, Dominican Republic ( USNM 367242); Les Cayes, Dept. du Sud, Haiti ( USNM 440369); Lucea, Jamaica ( BMNH 20081008).

This species is common on the continental shores and high islands of the Caribbean Sea. It is virtually absent from the oceanic eastern side of the Yucatan Peninsula (a single specimen recorded). In Belize it is rare on offshore cays, but common on the mainland. Further south, it is absent from the sedimentary shores of Honduras and Nicaragua, but frequent on the Caribbean mainland from Costa Rica to Venezuela. Flores (1973a, b) gave detailed records for Venezuela; although there are a few specimens from the offshore islands such as Los Roques, the species is much more common on the mainland and penetrates into the Gulf of Paria. In the Netherlands Antilles there is only a single record from Aruba, but it is frequent on the more continental islands of Isla Margarita and Trinidad. It is also common in Tobago, Granada and Barbados, and there are sporadic records from the larger islands in the Lesser Antilles (St Vincent, Martinique, Guadeloupe, St Lucia, Antigua). In the Virgin Islands it is recorded only from St Thomas. In the Greater Antilles it is common in Puerto Rico and there are records from northeast and southwest Hispaniola. In Jamaica it is common in the south and west, but rare on the more exposed northeast coast. There are no confirmed records from Cuba (a single unlocalized lot in BMNH) and none from the Bahamas.

Habitat: On sandstone, limestone and concrete, in littoral fringe and uppermost eulittoral zone, on moderately sheltered shores. Largely restricted to continental settings with slightly to moderately turbid water.

At Santa Marta, Colombia, E. interrupta is zoned above E. ziczac on shale cliffs, overlapping with E. tuberculata ( Bandel 1974a; Bandel & Wedler 1987). It hides in crevices and also occupies pools of highly variable salinity; smaller individuals occur in pools of normal salinity close to the high tide level ( Bandel 1974a). In Venezuela Flores (1973a) reported it on both sheltered rocks and exposed cliffs. Here it occupies the lower littoral fringe and is preyed upon by Stramonita haemastoma (Linnaeus) ; it is the most euryhaline of Echinolittorina species in Venezuela, tolerating salinities of 5–36 ppt ( Flores 1973b). Veligers hatch from the egg capsules after 3 days ( Bandel 1974a).

Remarks: Distinction of E. interrupta from its sister species E. placida is described in the Remarks on the latter and summarized in Table 1.

These two species are never sympatric, but share a similarly continental habitat preference, being common on eutrophic mainland coasts (and in the case of E. interrupta on large high islands), but virtually absent from oceanic peninsulas and coral cays. Together these occur under the most continental conditions of all the western Atlantic Echinolittorina species. The presence of E. interrupta in the southern Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico can be ascribed to the influence of the Orinoco plume, which causes nutrient enrichment in the eastern Caribbean Sea during the summer wet season ( Hu et al. 2004). Its presence in the northern Lesser Antilles is surprising, but museum records suggest that it is far less common there than its more oceanic congeners E. ziczac , E. angustior , E. jamaicensis and E. tuberculata . The distributions of the most oceanic of the Caribbean Echinolittorina species , E. mespillum , and the most continental, E. interrupta , are almost mutually exclusive; in the entire Caribbean Sea they have been recorded from the same localities (i.e. at the scale of small islands) only five times ( Aruba, St Vincent, Barbados, Guadeloupe, north Jamaica).

There is some regional variation in the shells. Those from Panama, Costa Rica and western Jamaica often have a strong peripheral keel, elongate form, clear spiral sculpture, and the spiral black band is often absent on the last whorl ( Fig. 22E, H–M View FIGURE 22 ). In the rest of the Caribbean Sea the shape is less elongate, slightly succineiform, sculpture often becomes obsolete on the last whorl, and the colour pattern is very dark, the spiral band remaining distinct on the last whorl ( Fig. 22A–D, F, G View FIGURE 22 ). Molecular data are available only for the former, so their conspecificity remains to be tested. There is also slight sexual dimorphism within some populations, so that smaller and more patulous forms (such as Fig. 22D View FIGURE 22 ) are more likely to be males.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Echinolittorina interrupta

| Reid, David G. 2009 |

Echinolittorina interrupta

| Williams, S. T. & Reid, D. G. 2004: 2227 |

| Williams, S. T. & Reid, D. G. & Littlewood, D. T. J. 2003: 60 |

Littorina angustior

| Diaz, J. M. & Puyana, M. 1994: 124 |

Nodilittorina interrupta

| Reid, D. G. 2002: 259 |

| Britton, J. C. & Morton, B. 1989: 86 |

Nodilittorina (Echinolittorina) interrupta

| Taylor, J. D. & Reid, D. G. 1990: 208 |

| Reid, D. G. 1989: 99 |

Littorina interrupta

| Diaz, J. M. & Puyana, M. 1994: 124 |

| De Jong, K. M. & Coomans, H. E. 1988: 19 |

Littorina lineata

| Borkowski, T. V. 1975: 369 |

Littorina (Melarhaphe) lineata

| Martens, E. von & Godman, F. D. & Salvin, O. 1900: 583 |

Littorina (Melarhaphe) philippii var. latistrigata von Martens, 1900: 577

| Reid, D. G. 2002: 88 |

| Martens, E. von & Godman, F. D. & Salvin, O. 1900: 577 |

Littorina (Melarhaphe) ziczac

| Tryon, G. W. 1887: 251 |

Littorina (Melarhaphe) floccosa

| Morch, O. A. L. 1876: 138 |

Phasianella lineata

| Lamarck, J. B. P. A. de 1822: 54 |

Trochus ziczac

| Gmelin, J. F. 1791: 3587 |