Echinolittorina placida, Reid, 2009

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2184.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D3606F-A53D-FFA8-FF26-FDF1FE92FCF6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Echinolittorina placida |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Echinolittorina placida View in CoL new species

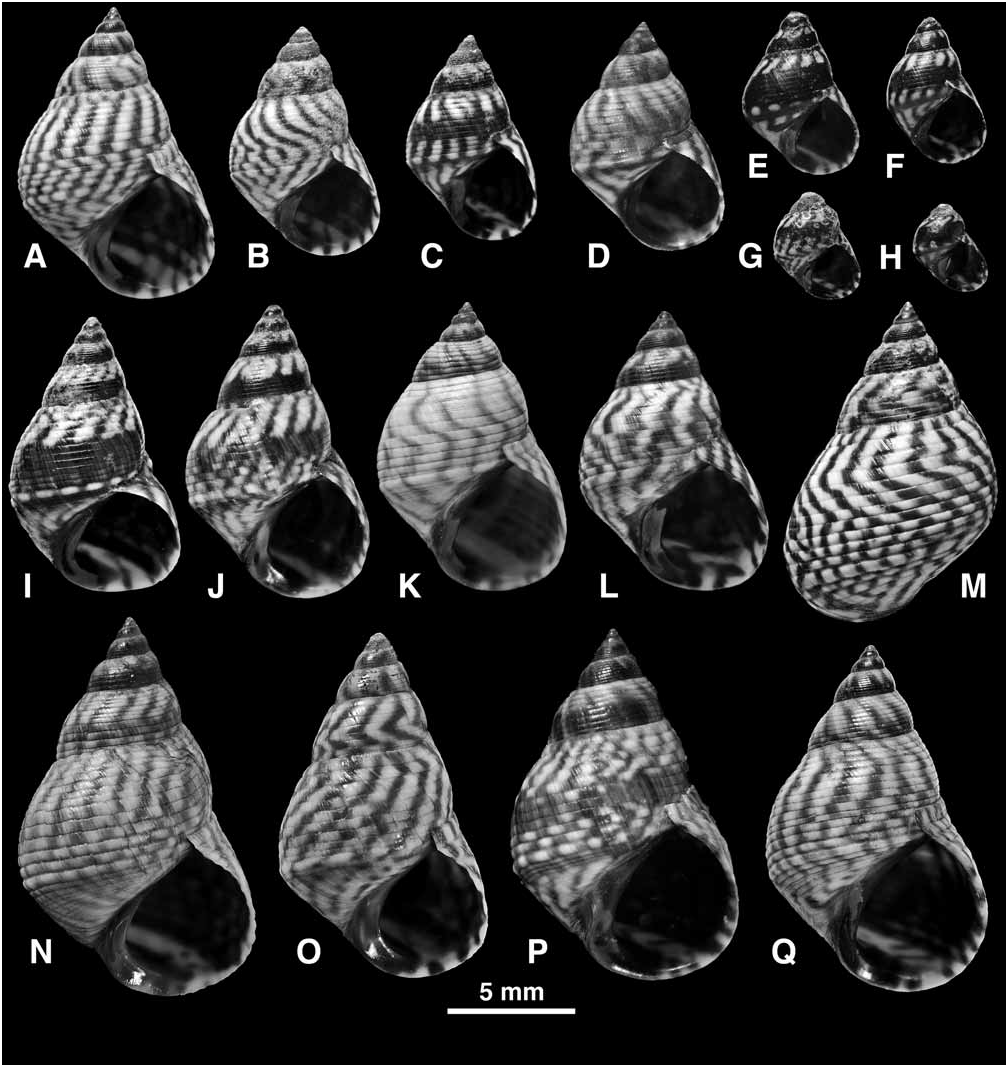

( Figures 16E, F View FIGURE 16 , 24–26 View FIGURE 24 View FIGURE 25 View FIGURE 26 )

Littorina ziczac View in CoL — Bequaert, 1943: 14–18 (in part, includes E. interrupta View in CoL , E. lineolata View in CoL , E. ziczac View in CoL , E. jamaicensis View in CoL , E. angustior View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791). Whitten, Rosene & Hedgpeth, 1950: 82 (not Gmelin, 1791). Abbott, 1954a: 132 (in part, includes E. angustior View in CoL , E. jamaicensis View in CoL , E. ziczac View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791). Smalley, 1970: 35–36 (not Gmelin, 1791).

Littorina (Melarapha) ziczac View in CoL — Rehder, 1962: 122 (in part, includes E. angustior View in CoL , E. lineolata View in CoL , E. ziczac View in CoL ; not Gmelin, 1791).

Littorina lineolata View in CoL — Abbott, 1964: 65–66 (in part, includes E. angustior View in CoL , E. jamaicensis View in CoL ; not d’Orbigny, 1840). Bingham, 1973: 250 (not d’Orbigny, 1840). García-Cubas, 1981: 19–20, fig. 9 (not d’Orbigny, 1840). Wiley, Circe & Tunnell, 1982: 55–61 (not d’Orbigny, 1840).

Littorina (Austrolittorina) lineolata View in CoL — Abbott, 1974: 563 (in part, includes E. jamaicensis View in CoL ; not d’Orbigny, 1840). Andrews, 1977: 79, fig. (not d’Orbigny, 1840). H.E. Vokes & E.H. Vokes, 1983: 14, pl. 4, fig. 2 (not d’Orbigny, 1840).

Nodilittorina lineolata View in CoL — Britton & Morton, 1989: 48–49, 86, col. pl., figs 3-1, 3-4, 4-1, 4-2, 4-3, 4-5A, 5-1 (in part, includes E. lineolata View in CoL ; not d’Orbigny, 1840).

Echinolittorina interrupta View in CoL — Williams & Reid, 2004: 2227–2251, fig. 6E (map) (in part, includes E. interrupta View in CoL ; not C.B. Adams in Philippi, 1847).

Types: Holotype BMNH 20081009 ( Fig. 25A View FIGURE 25 ); 12 dry paratypes BMNH 20081010 /1 ( Fig. 25B, C View FIGURE 25 ); 100 alcohol paratypes BMNH 20081010 /2; 4 dry paratypes USNM 1125113; Marco I., Collier Co., Florida , USA.

Etymology: Latin, quiet or still, in reference to the predominantly sheltered habitats of the species.

Taxonomic history: This species has seldom been reported in the literature, and appears to have been figured only four times ( Andrews 1977; García-Cubas 1981; H.E. Vokes & E.H. Vokes 1983; Britton & Morton 1989). Bequaert (1943), Abbott (1954a) and Rehder (1962) simply noted that the range of ‘ L. ziczac ’ extends to Texas, where in fact the only abundant Echinolittorina is E. placida . Abbott (1964) distinguished two species in the ‘ ziczac ’ group, including the present species under L. lineolata . He may later have considered that Texan specimens belonged to two species, since he mentioned that both L. lineolata and L. angustior occur in Texas ( Abbott 1974), although E. angustior has not been recorded there. As further species were distinguished in the ‘ ziczac ’ group the name L. lineolata continued to be used for the present species ( Bingham 1973; Andrews 1977; García-Cubas 1981; H.E. Vokes & E.H. Vokes 1983), although the name was also applied to the more strongly sculptured E. jamaicensis in Florida and the Caribbean (e.g. T.V. Borkowski & M.R. Borkowski 1969; Abbott 1974). In their revision of western Atlantic Nodilittorina, Bandel & Kadolsky (1982) did not examine material from the Gulf of Mexico, reporting N. interrupta only from the Caribbean Sea and restricting the use of the name N. lineolata to a species from Brazil. Nevertheless, Britton & Morton (1989) continued to employ the name N. lineolata for the present species in Texas, while discussing the taxonomic uncertainty and even remarking that the Texan form might be a distinct species ( Britton & Morton 1989: 49). Following the species taxonomy of Bandel & Kadolsky (1982), Reid (1989, 2002a, as Nodilittorina ) and Williams & Reid (2004) identified material from Mexico, Texas, Florida and Carolina as E. interrupta , here shown to be restricted to the Caribbean Sea.

Diagnosis: Shell of medium size; whorls rounded; 7–8 primary spiral grooves; secondary grooves few or absent; grooves distinct on last whorl; dark oblique axial lines, broad black spiral band above suture on spire becoming indistinct on last two whorls. Penis with tapering filament thickened and glandular at base, glandular disc projects as a lobe. Continental shores of Gulf of Mexico, Atlantic coast of Florida to N Carolina. COI: GenBank AM941714 View Materials , FN298402 View Materials , FN298403 View Materials .

Material examined: 71 lots (including 17 penes, 7 sperm samples, 5 pallial oviducts, 1 spawn sample, 2 radulae).

Shell ( Fig. 25 View FIGURE 25 ): Mature shell height 2.8–19.9 mm. Shape high turbinate or tall (H/B = 1.35–1.75, SH = 1.51–1.97); spire whorls moderately rounded; suture distinct; spire profile straight; periphery of last whorl slightly angled. Columella short, slightly hollowed and pinched at base; eroded parietal area small or absent. Sculpture of 7–8 primary spiral grooves on spire whorls; secondary grooves absent, or a few may appear by division or interpolation at shoulder and near periphery and on base, giving 10–13 incised lines above periphery and 7–13 on base ( Fig. 25A, Q View FIGURE 25 ); grooves usually distinct, reaching one third rib width just above periphery; peripheral rib usually slightly enlarged; sculpture may become obsolete in stunted forms ( Fig. 25E, G, H View FIGURE 25 ); spiral microstriae absent. Protoconch 0.28–0.30 mm diameter, 2.4–2.7 whorls. Ground colour white with narrow oblique undulating or zigzag brown to black lines; lines may break up into tessellation above periphery ( Fig. 25J, N, P View FIGURE 25 ); grey or black band on lower half of spire whorls, usually becoming indistinct on penultimate and last whorls; stunted shells often entirely blackish brown with 3 rows of short white stripes at suture, periphery and on base ( Fig. 25E–H View FIGURE 25 ); aperture dark brown with pale band at base and at shoulder; columella purple brown.

Animal: Head ( Fig. 26F View FIGURE 26 ) black, no unpigmented stripe across snout; tentacle pale around eye, with two broad longitudinal black stripes (sometimes almost fused) and black tip; sides of foot black. Opercular ratio 0.34–0.44. Penis ( Fig. 26A–H View FIGURE 26 ): filament with opaque glandular thickening at base, gradually tapering to pointed tip, 0.5–0.6 total length of penis, sperm groove ends terminally; mamilliform gland approximately same size as penial glandular disc, borne together on projection of base, disc projects as a lobe; penis unpigmented. Euspermatozoa 64–82 µm; paraspermatozoa ( Fig. 26K–M View FIGURE 26 ) containing single parallel-sided rod-piece with rounded ends, 12–22 µm, usually projecting from cell, which is packed with large round granules. Pallial oviduct ( Fig. 26I View FIGURE 26 ): copulatory bursa separates at half length of straight section from anterior end and extends back to albumen gland. Spawn ( Fig. 26J View FIGURE 26 ): an asymmetrically biconvex pelagic capsule 254–271 µm diameter, with broad peripheral rim overhanging base, dome-shaped upper side sculptured by 3 concentric rings, containing single ovum 83 µm diameter (capsules from single female from Fort Pierce, Florida, June 1985).

Radula ( Fig. 16E, F View FIGURE 16 ): Relative radula length 4.40–5.80. Rachidian: length/width 1.56–2.00; tip of major cusp pointed. Lateral and inner marginal: 4 cusps, tip of major cusp rounded. Outer marginal: 7–8 cusps.

Range ( Fig. 24 View FIGURE 24 ): North Carolina to Florida, Gulf of Mexico. Range limits: Wrightsville Beach, Wilmington, N Carolina ( BMNH 20081011); Bull I., N of Charleston, S Carolina ( BMNH); St Simon’s I., Glynn Co., Georgia ( BMNH); Cape Florida, Dade Co., Florida ( BMNH); Marco I., Collier Co., Florida ( BMNH 20081010); Tarpon Springs, Pinellas Co., Florida ( BMNH); Dauphin I., Alabama ( BMNH 20081017); Bayou LaFourche, Louisiana ( Smalley 1970); Sabine, Texas ( USNM 522727); Rockport, Aransas, Texas ( USNM 606001); Lobos Reef, Mexico ( USNM 710351); Veracruz, Mexico ( USNM 443814); Seybaplaya, Campeche, Mexico ( BMNH 20081015); Progreso, Yucatan, Mexico ( Britton & Morton 1989).

This species is now common on hard substrates all around the Gulf of Mexico, but this is a relatively recent phenomenon. The only natural rocky shoreline is in the southeast, on the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula and Veracruz State; the most northerly rocky outcrop on the east coast of Mexico is 75 km north of Veracruz City ( Britton & Morton 1989). Construction of jetties, breakwaters and sea walls since the late nineteenth century has allowed the spread of E. placida northwards to Texas and Louisiana. Although not recorded from Texas in the nineteenth century, it occurred as far north as the Sabine Pass in 1950 ( Whitten, Rosene & Hedgpeth 1950; Hedgpeth 1953). It was discovered in Louisiana in 1960 ( Smalley 1970) and in Panama City on the west coast of Florida in 1971 ( Bingham 1973). A collection was made from Pinellas County in 1981 ( USNM 820422, the only twentieth century material from Florida in USNM), and a large collection from Collier County in 1987 ( BMNH 20081010). Colonization of the Atlantic coast of Florida and further north has apparently occurred more recently. It was not found in the Carolinas in 1947 (A. Stephenson & T.A. Stephenson 1952). In 1985 a single specimen was found at Fort Pierce Inlet ( BMNH 20081022), but no others during extensive collections of littorinids in this and other inlets (Sebastian and Jupiter Inlets; pers. obs.). However, from 1992 onwards the species has been found commonly in the inlets on the east coast of Florida, on both beachrock and artificial substrates (25 lots in BMNH, collections by M. Krisberg). The most northerly collection was made on an isolated rocky shore near Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1995 ( BMNH 20081011). This population was reported to be of sporadic, ephemeral occurrence (J. Geller, pers. comm., 1995), suggesting repeated colonization from further south. Specimens were collected close by at Fort Fisher ( BMNH) in 2007.

Habitat: On natural outcrops of limestone and ‘coquina’ beachrock, also on granite, sandstone, limestone and concrete jetties, rarely on wood pilings, in littoral fringe and uppermost eulittoral zone, on moderately sheltered shores and in inlets. Restricted to continental, lagoonal and estuarine settings, with moderately turbid water.

The most detailed information on this species can be found in Britton & Morton’s (1989) account of the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico. It is one of the most characteristic inhabitants of the simple intertidal communities on the man-made jetties that protect sea channels all around the Gulf (see also Whitten et al. 1950). Snails cluster in crevices in the littoral fringe on both moderately exposed and sheltered faces of jetties, and extend down into the barnacle zone of the eulittoral. Specimens on granite rocks are on average 2-3 mm smaller than those from limestone, perhaps because the latter habitat provides more abundant algal food and eroded pits offer protection from waves that would dislodge large snails. It also extends into sheltered tidal inlets, suggesting tolerance of a range of salinity ( Hedgpeth 1953), and can occasionally be found on wooden pilings. Juveniles appear throughout the summer, with a peak of recruitment in the autumn. It is found also on natural igneous outcrops in Veracruz, and on limestone shores in western and northern Yucatan. García-Cubas (1981) reported it to be common in a lagoonal system in Campeche. The heat coma temperture is 44.4°C ( McMahon 2001) and acute upper thermal limit (LT 50) is 52.3°C ( McMahon 1992).

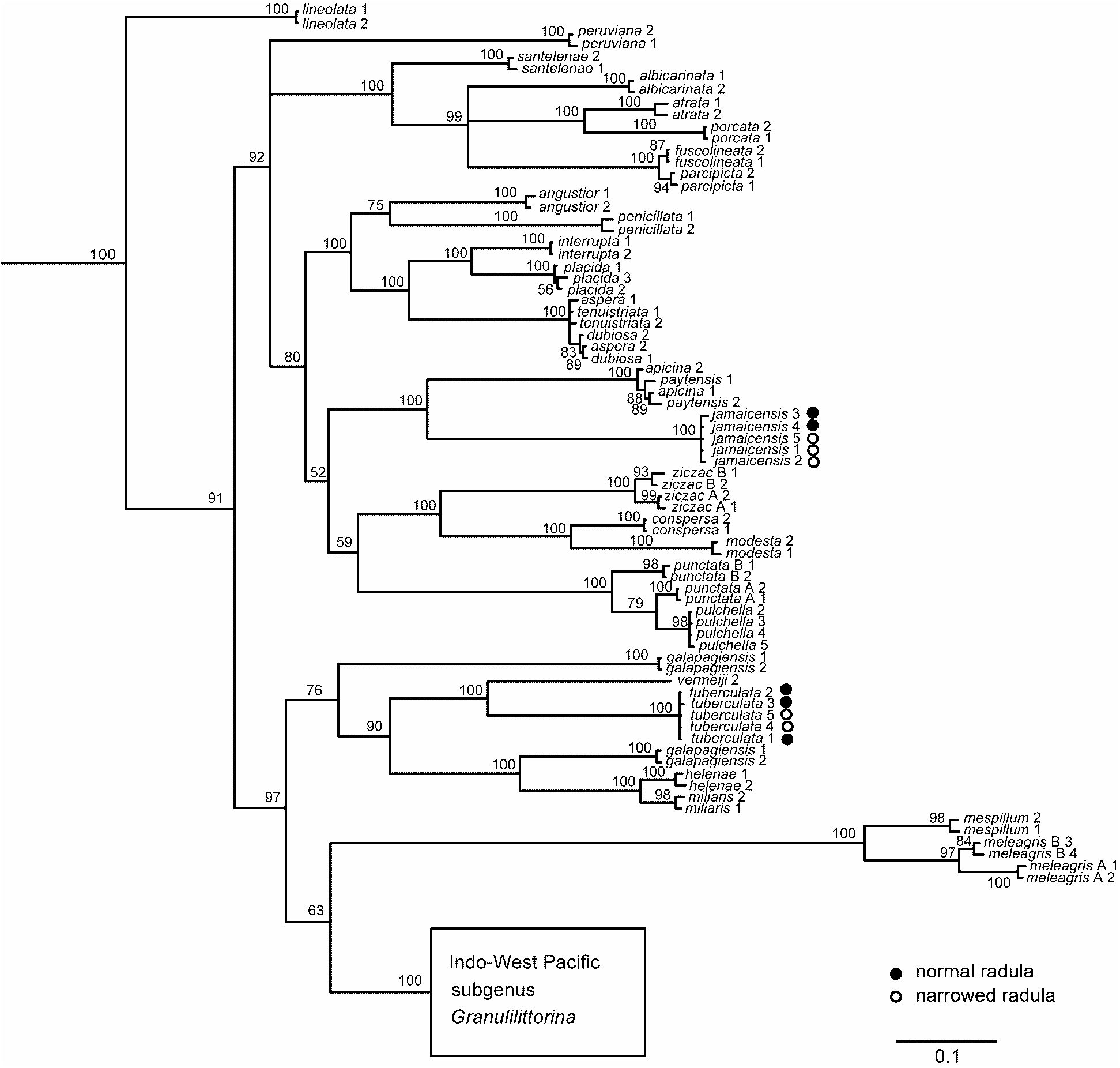

Remarks: This species has previously been identified as a form of E. interrupta . However, shells from the Gulf of Mexico and southeastern United States are distinctive, with a more rounded whorl profile, fewer primary grooves (7–8, compared to 8–10), stronger grooves on the final whorl, less prominent spiral black band on the spire, and tendency to tessellation of the striped pattern, in comparison with typical E. interrupta ( Table 1). These two are almost identical anatomically, but the lateral branch of the penis is slightly longer and the penial glandular disc forms a more prominent lobe in E. placida . Both forms show a relatively continental distribution, but E. placida appears to be more tolerant of sheltered, turbid and even estuarine conditions, and is absent from islands close to the mainland such as the Florida Keys and northern Bahamas. While E. interrupta likewise occurs on mainland coasts and is sparse on adjacent islands, it does extend to the small, high islands of the Lesser Antilles, and to Hispaniola and Jamaica, where conditions are more oceanic. Support for their status as separate species also comes from closely similar COI sequences of E. placida from Campeche, Louisiana and eastern Florida (K2P genetic distance 0.42–0.93%; Fig. 37 View FIGURE 37 ), contrasting with a genetic distance of 7.52–8.10% between these and corresponding sequences of E. interrupta from Jamaica and Panama. This falls within the range of distances between other sister-species pairs in Echinolittorina ( Reid et al. 2006; Reid 2007). So far there are no data from nuclear genes to corroborate the distinction, but it is assumed that the small but consistent morphological differences have a genetic basis.

The geographical distributions of the two sister species are not known to overlap ( Fig. 24 View FIGURE 24 ). Echinolittorina interrupta is limited to the Caribbean Sea; it has not been recorded from Cuba or the Bahamas and only a single specimen has been found on the eastern side of the Yucatan Peninsula. With the exception of this specimen, there is a broad swath of the northern Caribbean Sea where neither species occurs. This corresponds with an area of oceanic conditions with clear water of low productivity, and it is probably this unsuitable habitat that maintains the separation of E. placida and E. interrupta . The contrast between the turbid, eutrophic waters on the western side of the Yucatan Peninsula where E. placida occurs and the clear, coral-rich sea on the eastern side where it does not is striking (H.E. Vokes & E.H. Vokes 1983; Britton & Morton 1989). Surface currents flow northwards through the Yucatan Channel into the Gulf of Mexico ( Hedgpeth 1953); although this may be responsible for the occasional presence of E. jamaicensis , E. ziczac and E. meleagris in the southern Gulf, there is no evidence for a similar spread of E. interrupta .

As discussed above, the distribution of E. placida along the sedimentary coastline of the Gulf of Mexico can only have been achieved since the widespread construction of jetties and other rocky structures after the late nineteenth century. Spread to northern Texas ( Whitten et al. 1950), Louisiana ( Smalley 1970) and western Florida ( Bingham 1973) has been documented in the literature, and its abundance in eastern Florida has been achieved only since the 1990s. Surface currents flow northwards along the coast of Texas and eastwards through the Straits of Florida ( Hedgpeth 1953), and would therefore favour dispersal of planktonic stages around the Gulf and into the Atlantic. In the Gulf of Mexico natural rocky shores are largely restricted to the southern part, comprising a few limestone outcrops on the northern and western Yucatan Peninsula, and two larger outcrops of igneous rock in central Veracruz ( Britton & Morton 1989). On the Gulf coast of Florida there are a very few limestone rocks (D.S. Jones, pers. comm.), considerable limestone platforms in the Florida Keys (T.A. Stephenson & A. Stephenson 1950) and sparse outcrops of beachrock on the Atlantic coast of Florida (A. Stephenson & T.A. Stephenson 1952). However, E. placida does not occur in the Florida Keys and there is no evidence that it occurred in western Florida until 1985. It must be assumed that the natural distribution of E. placida is on the sparse rocky outcrops of the southern Gulf of Mexico and therefore of extremely narrow extent. Its rapid expansion along 4500 km of coastline as far as North Carolina, in about 100 years, is remarkable. While other environmental or climatic changes may have contributed, this spread could not have been achieved without the construction of jetties and sea walls on an otherwise uninhabitable coastline.

| USNM |

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Echinolittorina placida

| Reid, David G. 2009 |

Echinolittorina interrupta

| Williams, S. T. & Reid, D. G. 2004: 2227 |

Nodilittorina lineolata

| Britton, J. C. & Morton, B. 1989: 48 |

Littorina (Austrolittorina) lineolata

| Vokes, H. E. & Vokes, E. H. 1983: 14 |

| Andrews, J. 1977: 79 |

| Abbott, R. T. 1974: 563 |

Littorina lineolata

| Wiley, G. N. & Circe, R. C. & Tunnell, J. W. 1982: 55 |

| Garcia-Cubas, A. 1981: 19 |

| Bingham, F. O. 1973: 250 |

| Abbott, R. T. 1964: 65 |

Littorina (Melarapha) ziczac

| Rehder, H. A. 1962: 122 |