Omocestus viridulus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4895.4.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:002F9E9D-43AA-4CD3-89FB-FD41EEEE4B18 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4362343 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D81D4E-FFC3-0E1C-FF4E-F9A84AA51FF4 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Omocestus viridulus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| status |

|

Omocestus viridulus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Distribution. From Western Europe to Siberia and Mongolia, moist habitats.

Material. 17. Russia, Altai Republic, ab. 26 km S of Shebalino, Semensky pass, 51°02.6’ N, 85°36.3’ E, 1705 m a.s.l., 07.08.2017, song recordings in 2 ³ GoogleMaps .

References to song. Faber, 1953: verbal description only, calling and courtship songs; Elsner, 1974: recordings from Germany, courtship song; Waeber, 1989: recordings from Austria, courtship song; Hedwig & Heinrich, 1997: recordings from Germany, courtship song; Ragge & Reynolds, 1998: recordings from England, France and Spain, calling and courtship songs; Savitsky, 2005: recordings from the Caucasus, calling and courtship songs; Tishechkin & Bukhvalova, 2009a, b: recordings from Russia (Moscow region, Altai and Irkutsk region), calling song; Willemse et al., 2018: recordings from Greece, calling song.

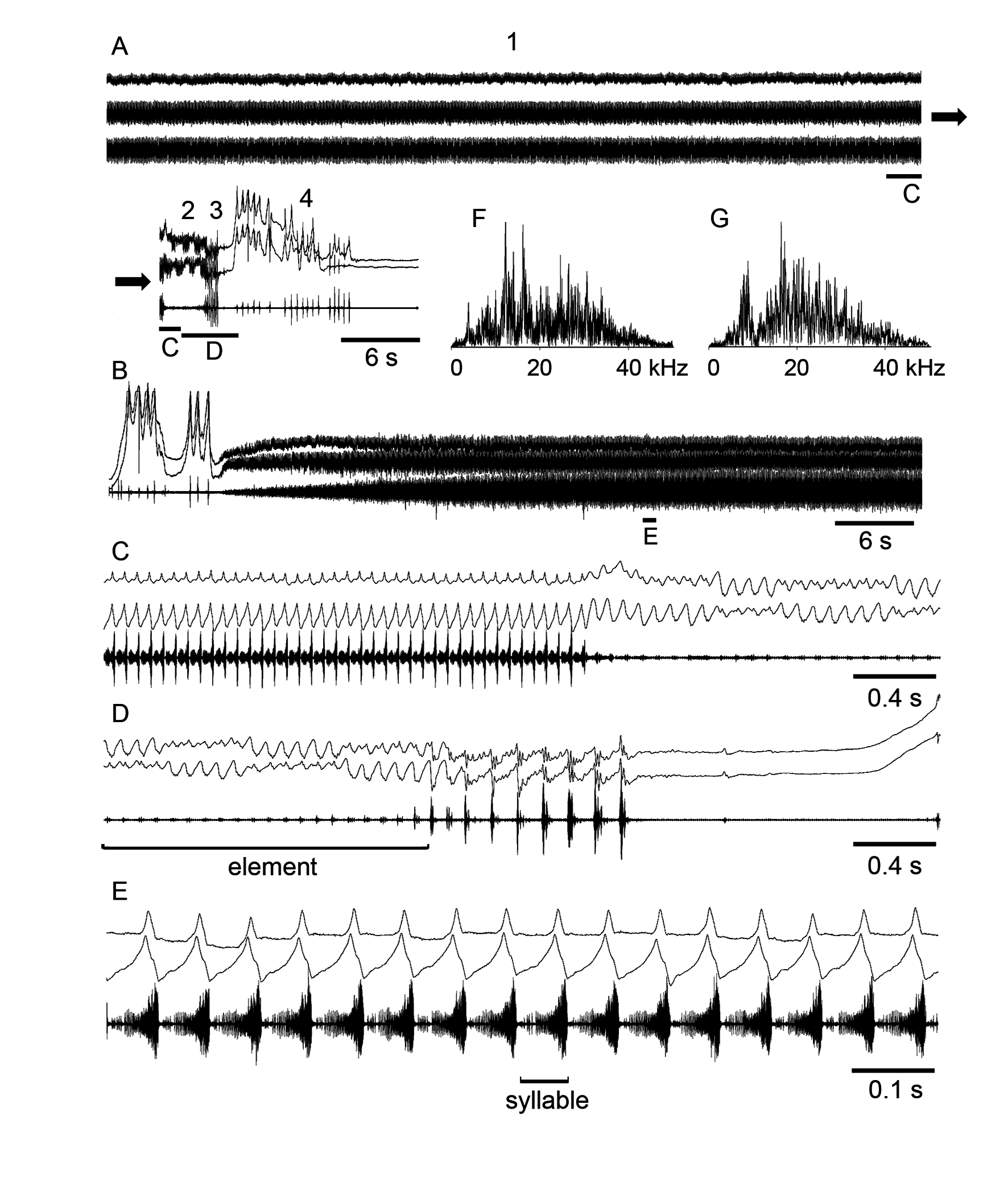

Song. The first part of the courtship song (element 1) is similar to the calling song, but of longer duration (1–3 min, Fig. 2 A, B View FIGURE 2 ). It comprises an echeme consisting of syllables repeated at the rate of about 16–19/s. The echeme begins quietly reaching a maximum intensity after about 20 s. One hind leg is usually moved at a larger angle and with a slightly different pattern (leading leg) than the other leg ( Fig. 2 C, E View FIGURE 2 ). After the element 1, there comes a completely different and much quieter echeme lasting 3–5 s (element 2, Fig. 2 C, D View FIGURE 2 ). The two legs start to alternate movements at the rate of about 13–15/s in a conspicuous manner: the leading leg moves with a larger amplitude producing simple up and down movements and the other leg moves with a smaller amplitude producing a more complex pattern. This complex pattern implies every two up and down leg-movements to be coupled in a characteristic way. Both legs repeatedly change their pattern in such a way that the leading leg produces the longer sequences of the high-amplitude movements than the other leg. This is followed by a series of loud syllables repeated at the rate of about 6–8/s (element 3, Fig. 2 D View FIGURE 2 ). During this element lasting about 1– 1.5 s, the two legs are moved almost synchronously. Each syllable consists of one large and one or two small pulses. In about two seconds after the end of the element 3, the male raises both hind femora almost vertically and produces several pulses with irregular intervals of about 400–800 ms (element 4). These pulses, however, may also be produced just immediately before the first part of the courtship song ( Fig. 2 B View FIGURE 2 ). The frequency spectra of the sound produced during various elements of the courtship song are broad, with a slightly different dominant frequencies for the first element (about 12 and 18 kHz) and for the third element (about 8 and 18 kHz) ( Fig. 2 F, G View FIGURE 2 ).

Comparative remarks. Our recordings of the courtship songs of the specimens from Altai do not principally differ from the song recordings from Western Europe ( Elsner, 1974; Waeber, 1989; Hedwig & Heinrich, 1997; Ragge & Reynolds, 1998). The authors, however, sometimes confused the pulses of the elements 3 and 4 of the courtship song, considering all of them as the pulses generated by ‘precopulatory movements’ that are followed by an attempt to copulate with a female. This confusion could originate from the similarity of the pulse structure in these elements of courtship. However, it must be emphasized that the above pulses are produced by completely different leg movements. Generation of the irregular pulses (the element 4) is apparently accompanied by a visual display. Ragge & Reynolds (1998) describe this visual display as kicking backwards with the hind tibiae. Unfortunately, we did not make video-recordings of courtship in O. viridulus , and therefore, we cannot confirm the statement about the kicking with the tibiae. On the other hand, the high raising of the hind legs on our oscillograms may indicate that this kicking could occur.

Savitsky (2005) distinguish only two parts in the courtship song of O. viridulus from Caucasus. These song parts could correspond to the elements 1 and 3 in our recordings. We, however, suppose that the element 2, very quiet part of the courtship song, is also present in the recordings of Savitsky but the pulses of the small amplitude are almost invisible on the oscillograms. It is very likely that this part of the song generated by alternating movements of the two legs serves rather as a visual cue than as a sound signal.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |