Acanthoniscus spiniger Gosse, 1851

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1590/2358-2936e2023006 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4970E3C2-A1DB-4AAE8961-FBAA26505ED4AB |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10926651 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E987EB-FF03-FFE3-FE82-FC87FCB5FCC3 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Acanthoniscus spiniger Gosse, 1851 |

| status |

|

Acanthoniscus spiniger Gosse, 1851 View in CoL

( Figs. 1–2 View Figure 1 View Figure 2 )

Acanthoniscus spiniger White, 1847: 99 View in CoL (Nomen nudum). Schomburgk, 1848:658 (Nomen nudum).

Acanthoniscus spiniger Gosse, 1851: 65 View in CoL .

Acanthoniscus spiniger Kinahan,1859:197–198 View in CoL ,plate 200–201 (erroneously designated as the original description by Richardson, 1909). — Budde-Lund, 1879: 5. — Budde-Lund, 1885: 241. — Stebbing, 1893: 432. — Richardson, 1901: 569. — Richardson, 1905: 637 (repeated the description of Kinahan, 1859). — William T. Calman in Richardson, 1909: 434 (see Remarks). — Budde-Lund, 1910: 11 (partim). — Richardson, 1910: 495 (partim). — Arcangeli, 1927: 135 (partim). — Van Name, 1936: 402–403 (partim). — Clark and Presswell, 2001: 154. — Schmalfuss, 2003: 4 (partim). — Schmidt and Leistikow, 2004: 4 (partim). — Jass and Klausmeier, 2006: 4, 6, 25 (partim).

Type material. 1 ♀, holotype, BMNH 1973.478 .1. Jamaica. Examined by means of high-resolution pictures .

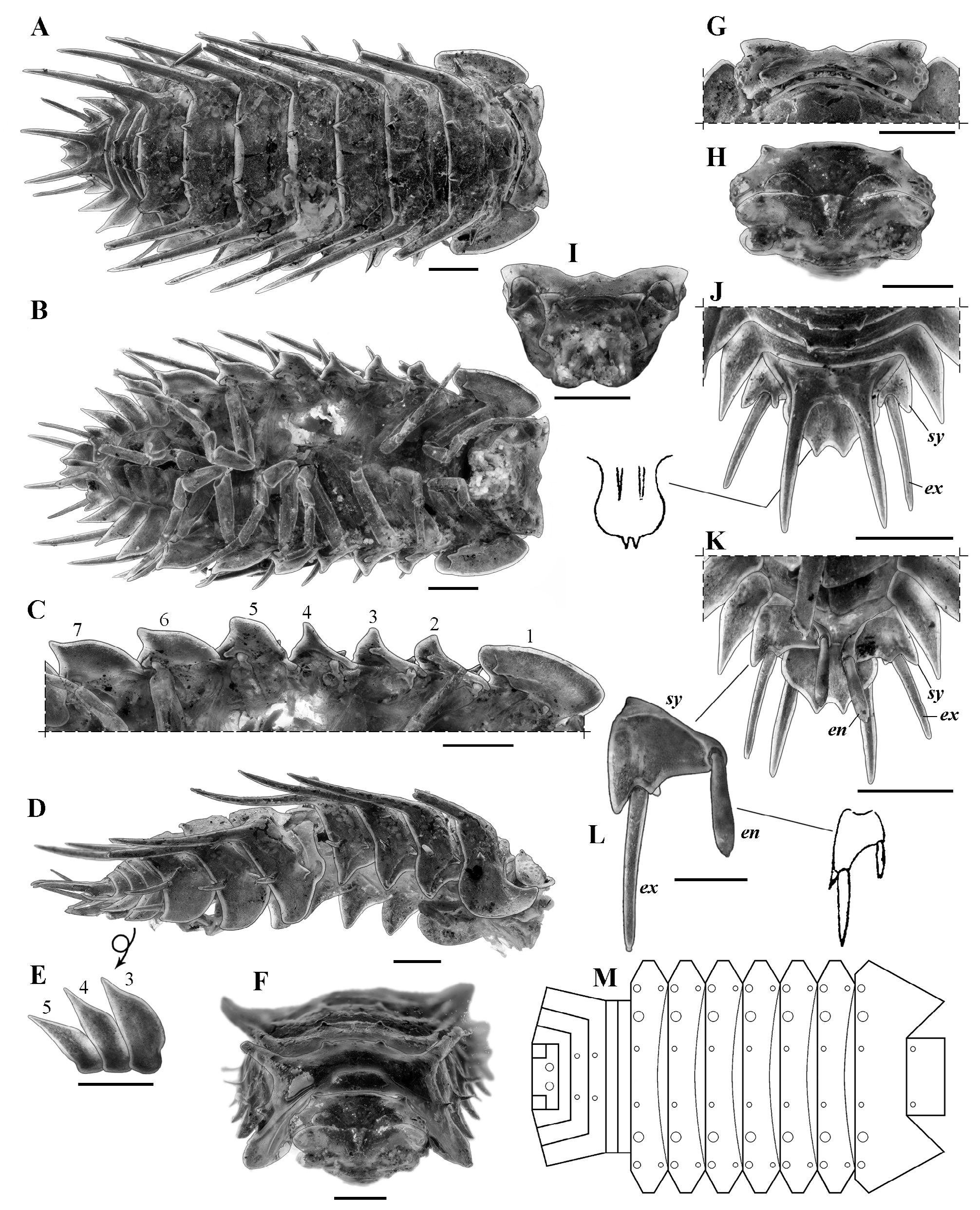

Diagnosis (emended). Total length: 9.9 mm (holotype). Cephalothorax with angulate lateral lobes and small, triangular median lobe (shorter than lateral lobes); dorsal surface with 2 small posteromedian spiniform tubercles ( Fig. 2D, G–I View Figure 2 ). Pereonites 1–7 with pair of small posteromedian spiniform tubercles, one on either side of median line ( Fig. 2A, D, F, M View Figure 2 ); epimera 2–7 similar and subtriangular ( Fig. 2B–D View Figure 2 ); coxal plates 5–7 with medium-sized submarginal tooth-like process, in basal position, just posterior to pereiopod junction, forming schisma ( Fig. 2C View Figure 2 ); the latter as single schisma engaging with contiguous posterior pereon epimera during conglobation. Pleonites 3–4 with pair of very small posteromedian spiniform tubercles; pleon epimera 3–5 with anterior margin slightly convex ( Fig. 2E View Figure 2 ). Pleotelson with posterior margin ending in 2 prominent triangular projections separated by deep notch ( Fig. 2D, J–K View Figure 2 ). Uropod sympodite “subtriangular,” outer margin slightly convex, medial-posterior angle triangular and not reaching distal margin of pleotelson; endopodite widely surpassing posterior margin of sympodite and almost reaching distal margin of pleotelson (not visible dorsally) ( Fig. 2J–L View Figure 2 ).

Cephalothorax ( Fig. 2G–I View Figure 2 ). More than 3 times (3.2) as wide as long, with angulate lateral lobes and small, triangular median lobe (shorter than lateral lobes). Dorsal surface with 2 small, posteromedian spiniform tubercles (one on either side of the median line) close to eyes.

Pereon ( Fig. 2A–D, F View Figure 2 ). Pereonite 1, 2.2 times as wide and 1.9 times as long as cephalothorax, with 2 very long, slightly sinuous dorsolateral spines (broken, but probably more than twice length of pereonite 1), pair of small posteromedian spiniform tubercles (one on either side of the median line), and smaller lateral spine on either side near posterior margin, directed backward; pereonites 2–7 similar, 3.5 times as wide as long (pereonite 7 slightly narrower), with 2 very long slightly sinuous dorsolateral spines (twice the length of pereonite 1), pair of small posteromedian spiniform tubercles (one on either side of median line), smaller lateral spine on either side near posterior margin, slightly curved and directed backward (gradually increasing in length posteriorly, being lateral spines of seventh tergite about half as long as dorsolateral spines), and spiniform tubercle near anterior margin and directed forward (engaging with previous tergite during conglobation, decreasing in size posteriorly, vestigial on pereonite 7). Epimera 1 with posterior angle and outer margin broadly rounded, anterior angle more acutely produced, dorsal surface concave; epimera 2–4 similar and subtriangular (epimera 4 only slightly differentiated from epimera 2–3), with anterior margin slightly concave and posterior margin slightly convex, outer angle acutely produced; epimera 5–7 more or less subtriangular, with anterior margin moderately convex and posterior margin concave, outer angle acutely produced and directed backward. Coxal plates 1–3 with small inner tooth-like process near posterior margin and directed backward, in medial position, forming small schisma and, in coxal plate 1, extending into shallow transversal groove toward base of coxa; coxal plate 4 without tooth-like processes; coxal plates 5–7 with medium-sized submarginal tooth-like process, in basal position, just posterior to pereiopod junction, forming schisma; the latter as single schisma engaging with contiguous posterior pereon epimera during conglobation.

Pleon ( Fig. 2A–B, D–E View Figure 2 ). Tergites 1, 2, and 5 without spines; tergites 3 and 4 with pair of very small posteromedian spiniform tubercles (one on either side of median line); epimera of pleonites 3–5 acutely produced, similar in shape and size, with anterior margin slightly convex, posterior margin straight, and outer angle acutely produced (sharp-pointed).

Pleotelson( Fig.2D,J–K View Figure 2 ).Basal part 1.7 times wider than distal part, 1.4 times as wide as long, with both dorsal spines 1.3 times as long as pleotelson; distal margin ending in 2 prominent triangular projections, separated by deep notch (0.8 times as deep as median diameter of pleotelson spines).

Uropods ( Fig. 2J–L View Figure 2 ). Sympodite subtriangular, 1.2 times as long as wide, ventral surface slightly concave (although it might be a consequence of dehydration during the time it was preserved dry, see Remarks), outer margin slightly convex, medial-posterior angle triangular and not reaching posterior margin of pleotelson, medial margin with well-developed, produced inner lobe above and basal with respect to insertion of exopodite; endopodite widely surpassing posterior margin of sympodite and almost reaching distal margin of pleotelson (not visible dorsally); exopodite nearly 1.5 times as long as sympodite and surpassing posterior margin of sympodite by 80% of its length.

Distribution. Known only from the type locality, “Bluefields Mountain” (sensu Gosse, 1851), which most certainly refers to the hills known as Surinam Quarters, immediately eastward and northward of Bluefields, Westmoreland Parish, southwestern Jamaica ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ; see Remarks).

Natural history. According to Gosse (1851), the area where A. spiniger was found (see Remarks) was in part covered with forest at the collection time (early February, 1845), but he made reference to the high level of disturbance because of agriculture (e.g., coffee, pimento, fruits, sugarcane), logging and livestock farming (see also Curtin, 1991; 2010; Scolaro, 2013). Indeed, he secured the isopod, together with some land snails, earthworms, and a small onychophoran, under stones “in a piece of ground just reclaimed from the forest, cleared and burnt over, but not yet planted, full of blackened stumps and stones” ( Gosse, 1851: 65).

Remarks.The holotype of A.spiniger is exceptionally well preserved given the time span since its collection (> 175 years); only the second antennae were missing, some pereiopods, mouth pieces, and some of the longest spines on the pereon were broken (two on pereonite 1, left on pereonite 4, and right on pereonite 7)( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). It was originally preserved dry and later it was transferred to ethanol, but it remains very rigid and the pleopods cannot be manipulated without risk of rupture, and the pin hole still can be observed in the right side of pereonite 4 (Miranda Lowe, in litt. 24.IX.2021; Fig. 2A–D View Figure 2 ).

Schmidt and Leistikow (2004) were the first authors to mention the catalog numbers associated with the holotype of A. spiniger deposited at the BMNH. The current catalog number appears in the Crustacea register (1969–1976, p. 119), as well as in the current on-line catalog ( Natural History Museum, 2014). Previous registration numbers: BMNH 1845.110 (Entomology register: Annulosa Vol. II, 1840–1849, p. 195: it says six crustacea specimens purchased from Mr. Gosse; Locality: Jamaica; but the remaining five specimens do not correspond to this species: Miranda Lowe, in litt. 24.IX and 7.XII.2021); White’s catalog no. 1024 (White’s Catalogue of Crustacea, Vol.III,1845–1847?, p. 1024: the precise date for this catalog is unknown, but falls within the previous range). The registration no. “1845.118” allocated by Ms. Joan Ellis (see also Schmidt and Leistikow, 2004: 4) is incorrect, the result of a mistake when doing the cross referencing, it should have said1845.110, since 1845.118 is allocated also to another batch of specimens in the same catalog (Crustacea register 1969–1976; Miranda Lowe, in litt. 24.IX and 7.XII.2021).

Jass and Klausmeier (2006) wrongly stated that “ Richardson [1909] redescribed the species under the genus Oniscus ,” probably because she cited the content of the original accompanying label that reads “ Oniscus spiniger ,” which does not constitute a published work and therefore it must not be considered a valid synonym ( ICZN, 1999: Art. 9); see Additional material under A. richardsonae sp. nov.

According to ICZN(1999:Art.12),“To be available, every new name published before 1931 must satisfy the provisions of Article 11 and must be accompanied by a description or a definition of the taxon that it denotes, or by an indication.” The way Schomburgk (1848) referred to the species (“spined”), seems most likely an extraction of evident information from the Latin name. However, “little dark grey Oniscus , every segment of which is armed with two spines,” as stated by Gosse (1851: 65), satisfies the concept of description before 1931 (e.g., ICZN, 1999: Arts. 12 and 13), plus all the additional information provided by this author regarding the type locality and habitat (he was the collector of the type specimen, see below). Following the Principle of Priority ( ICZN, 1999: Art. 23), the author of A. spiniger , and therefore of the genus Acanthoniscus , must be Gosse (1851) and not Kinahan (1859). Gosse’s (1851) book is a published work within the meaning of the Code (Art. 8). Gosse in the same work wrote: “Twenty-four new species of animals are described in the following pages, distributed nearly equally through the classes of Mammalia, Reptiles, and Fishes. ” Many of those taxa are still recognized in the present day: i.e., the fishes Gambusia melapleura ( Gosse, 1851) ( Poeciliidae ), Jenkinsia lamprotaenia ( Gosse, 1851) ( Clupeidae ), Parexocoetus hillianus ( Gosse, 1851) ( Exocoetidae ), and Trinectes inscriptus ( Gosse, 1851) ( Achiridae ), the frog Eleutherodactylus luteolus ( Gosse, 1851) ( Eleutherodactylidae ), the snakes Hypsirhynchus ater ( Gosse, 1851) and H. callilaemus ( Gosse, 1851) ( Dipsadidae ), and the bat Pteronotus macleayii griseus ( Gosse, 1851) ( Mormoopidae ) (Wilson and Reeder, 2005; Froese and Pauly, 2021; Uetz et al., 2022; AmphibiaWeb, 2022). Furthermore, this is an unusual case in that there is an objective continuity in the taxonomic concept of Gosse (1851) and Kinahan (1859), since they refer to the same specimen and kept the binomen given by White (1847). This taxonomic concept was simply improved by Kinahan (1859), then by Richardson (1909) and now in the present contribution. Clark and Presswell (2001: 154) cited “ Acanthoniscus White (in Kinahan, 1859)” and “ Acanthoniscus spiniger White (in Kinahan, 1859),” which is wrong, since Kinahan (1859) just recognized a source that did not include a description, same as Gosse (1851).

Philip H. Gosse spent most of his time in Jamaica around Bluefields Bay ( Fig.1 View Figure 1 ), in the southwestern part of the island ( Gosse, 1851). The holotype was most certainly collected at “Bluefields Mountain,” which according to Gosse, refers to “the lofty mountain that rises behind” Bluefields, a town where he stayed for several months ( Gosse, 1851). He also commented: “A ride of four or five miles brought me to the brow of the mountain” ( Gosse, 1851: 61), which gives an idea of the proximity to Bluefields. Gosse even mentioned that as he “draw nearer the lofty summit […] Savannale-Mar [Savanna-la-Mar] […], St. John’s Point and even the extreme western headlands, North and South Negril appeared just at hand” ( Gosse, 1851: 62). Therefore, this “Bluefields Mountain” must certainly refer to the hills immediately eastward and northward of Bluefields, on the eastern side of Bluefields Bay, within a subcoastal mountainous area known as Suriname Quarters, Westmoreland Parish, southwestern Jamaica ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). These hills include elevations such as Bluefields Peak (794 m a.s.l.), Mount Pleasant (468 m a.s.l.), and Shafston (286 m a.s.l.) ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ; Scolaro, 2013). Gosse even made an estimate of 1,500 feet elevation (> 450 m; Gosse, 1851: 63) near the collection point, which coincides with the heights of the area. Moreover, he mentioned a higher peak nearby “covered with the original forest,” shaded and humid, with abundance of lycophytes and tree-ferns (Bluefields Peak?), suggesting that the collection point was not at the highest peak of these mountains ( Gosse, 1851: 66). Despite all the above information provided by Gosse, a precise locality within Jamaica was never mentioned for A. spiniger , neither in the description by Kinahan (1859) nor in further contributions redescribing, listing or just mentioning the species ( Budde-Lund, 1879; 1885; 1910; Stebbing, 1893; Richardson, 1901; 1905; 1909; 1910; Arcangeli, 1927; Schmalfuss, 2003; Schmidt and Leistikow, 2004; Jass and Klausmeier, 2006). The exception was Van Name (1936), who made reference to Gosse’s (1851) writings about the “Bluefields Mountains” as the collection site of this isopod.Therefore, according to the ICZN (1999: Art. 76) and given the impossibility to specify an exact collection point, these hills above 400 m elevation known as Surinam Quarters, immediately eastward and northward of Bluefields (approximate coordinates: 18°10’45”N 78°00’00”W; Fig.1 View Figure 1 ), Westmoreland Parish, must be considered the type locality of A. spiniger .

| T |

Tavera, Department of Geology and Geophysics |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Oniscidea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Acanthoniscus spiniger Gosse, 1851

| Rodríguez-Cabrera, Tomás M. & de Armas, Luis F. 2023 |

Acanthoniscus spiniger

| Jass J & Klausmeier B 2006: 4 |

| Schmidt C & Leistikow, A 2004: 4 |

| Schmalfuss H 2003: 4 |

| Clark PF & Presswell B 2001: 154 |

| Van Name W 1936: 402 |

| Arcangeli A 1927: 135 |

| Budde-Lund G 1910: 11 |

| Richardson H 1910: 495 |

| Richardson H 1909: 434 |

| Richardson H 1905: 637 |

| Richardson H 1901: 569 |

| Stebbing TRR 1893: 432 |

| Budde-Lund G 1885: 241 |

| Budde-Lund G 1879: 5 |

| Kinahan JR 1859: 198 |

Acanthoniscus spiniger

| Gosse PH 1851: 65 |

Acanthoniscus spiniger

| Schomburgk RH 1848: 658 |