Thysanarthria Orchymont, 1926

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.2478/aemnp-2019-0020 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9F309FCC-A2ED-47B9-BC37-D0C4A3B482E5 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4548819 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F387C5-7A2B-FFB9-FE9B-04EE3655BF1C |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Thysanarthria Orchymont, 1926 |

| status |

|

Thysanarthria Orchymont, 1926 View in CoL

Thysanarthria Orchymont, 1926a:195 View in CoL . Type species: Hydrobius atriceps Régimbart, 1903 View in CoL by original designation.

= Chaetarthriomorphus Chiesa, 1967: 276 View in CoL . Type species: C. sulcatus Chiesa, 1967 View in CoL by monotypy. Synonymized by HANSEN (1991: 126).

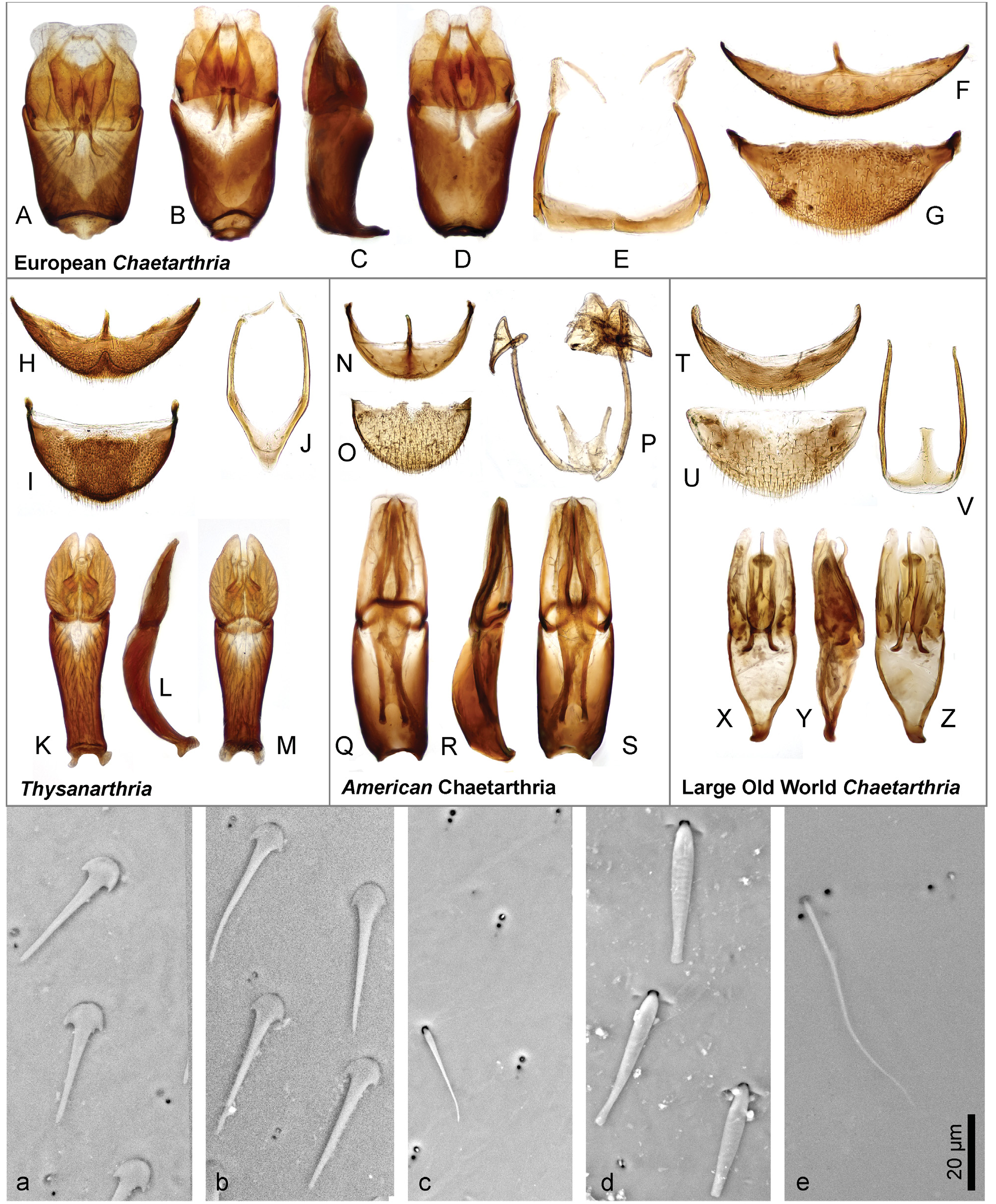

Diagnosis. The genus can be recognized from other co-occurring genera of the Hydrophilidae based on the following combination of characters: body small to medium sized (1.4–2.2 mm); head black, pronotum and elytra yellowish to pale brown in most species, uniformly brown in the remaining ones ( Figs 1 View Fig A–D); head with large exposed well sclerotized labrum (e.g., Fig. 1B View Fig ); antenna with 9 antennomeres, scape very long, pedicel bulbose, antennomeres 3–5 very small, cupule and three-segment antennal club pubescent ( Fig. 3D View Fig ); maxillary palpomere 4 basally with row of many peg-like setae ( Fig. 3E View Fig ); mentum projecting anteromedially, with row of setae along anterior margin ( Fig. 3A View Fig ); gular sutures contiguous ( Fig. 3C View Fig ); mesoventrite distinctly divided from anepisterna by sutures, sutures widely separated on anterior margin of mesothorax ( Fig. 3B View Fig ); mesoventrite flat except of small semicircular elevation posteromesally ( Fig. 3B View Fig ); metaventrite short, sparsely pubescent only mesally and anterolaterally ( Fig. 3B View Fig ); elytra with 10 sharply impressed striae ( Figs 1 View Fig A–D); whole dorsal surface covered by sparsely arranged setae which are trifid basally with a long median projection ( Figs 1C View Fig , 2 View Fig a–b); profemora pubescent in basal half ( Fig. 3C View Fig ); mesofemora pubescent anterobasally ( Fig. 3B View Fig ); metafemora bare except on anterobasal margins ( Fig. 3B View Fig ); tarsi rather short and stout, metatarsus with all tarsomeres c. equal in length ( Fig. 3F View Fig ); abdomen with 5 ventrites, basal two bearing shallow cavity covered by long setae arising from base of ventrite 1, holding whitish gelatinous substance ( Figs 3 View Fig G–H); ventrite 1–2 with median carina; male abdominal sternite 8 with narrow median projection ( Fig. 2H View Fig ); male sternite 9 V-shaped medially ( Fig. 2J View Fig ); aedeagus with long tubular phallobase, base of median lobe not reaching deeply into phallobase ( Figs 4–9 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig ).

Differential diagnosis. The base of abdomen with series of long setae covering a gelatinous substance and antenna with bulbous pedicel distinguish Thysanarthria from all other non-chaetarthriine genera. Within Chaetarthriini , the well sclerotized and widely exposed labrum differentiates it from Hemisphaera Pandellé, 1876 (which is also smaller and has more depressed body: see FIKÁČEK et al. 2012, JIA et al. 2013) which can co-occur with Thysanarthria , and from the Neotropical genus Guyanobius Spangler, 1986 (see GUSTAFSON & SHORT 2010). Thysanarthria can be distinguished from all three groups of Chaetarthria defined above by the elytra with 10 sharply impressed striae ( Figs 1 View Fig A–D). Most species of the genus are easy to recognize in the samples by their small body size and pale coloration of pronotum and elytra constrasting with the black head (this coloration is not present only in the Near East T. persica sp. nov. and T. wadicola sp. nov.).

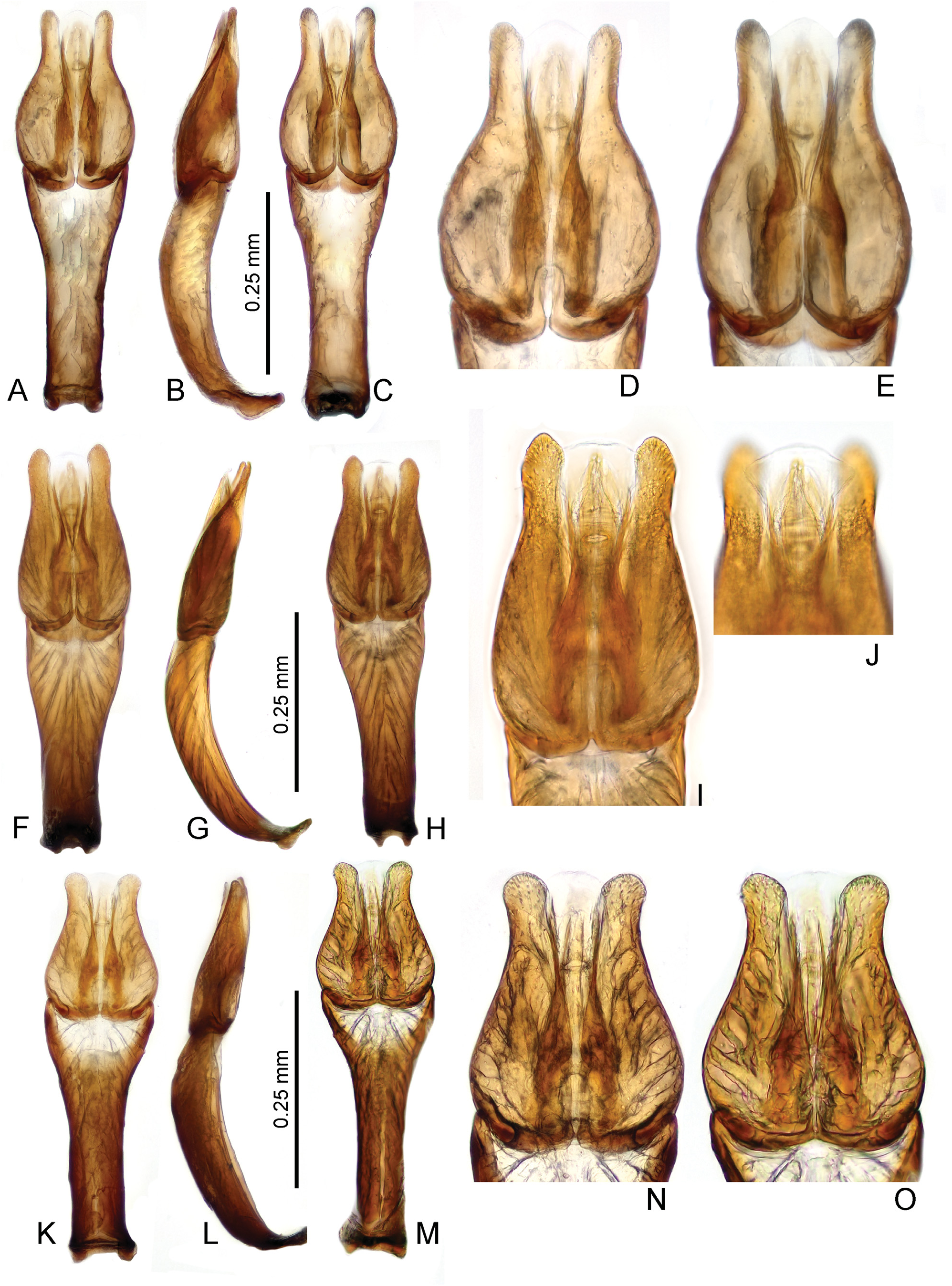

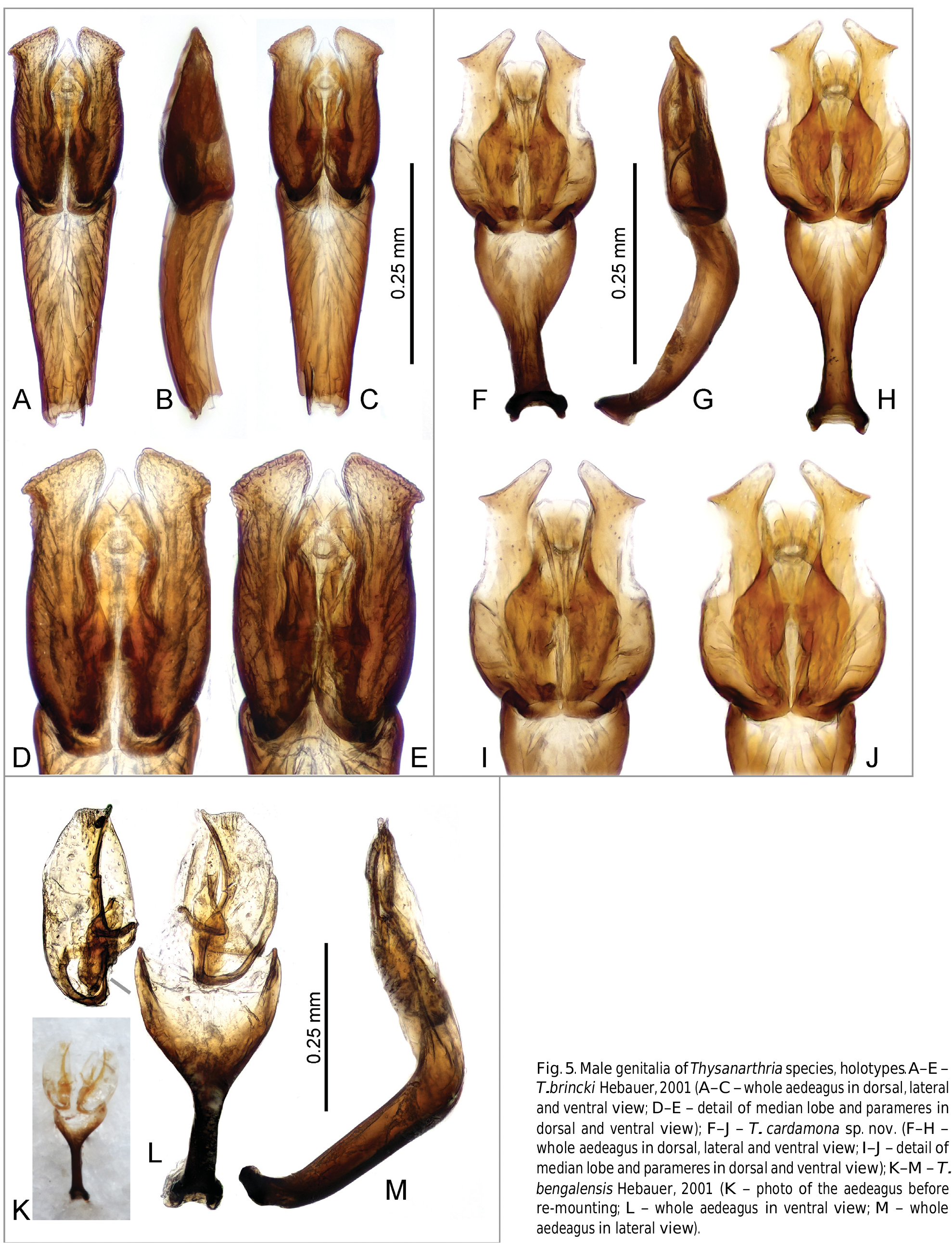

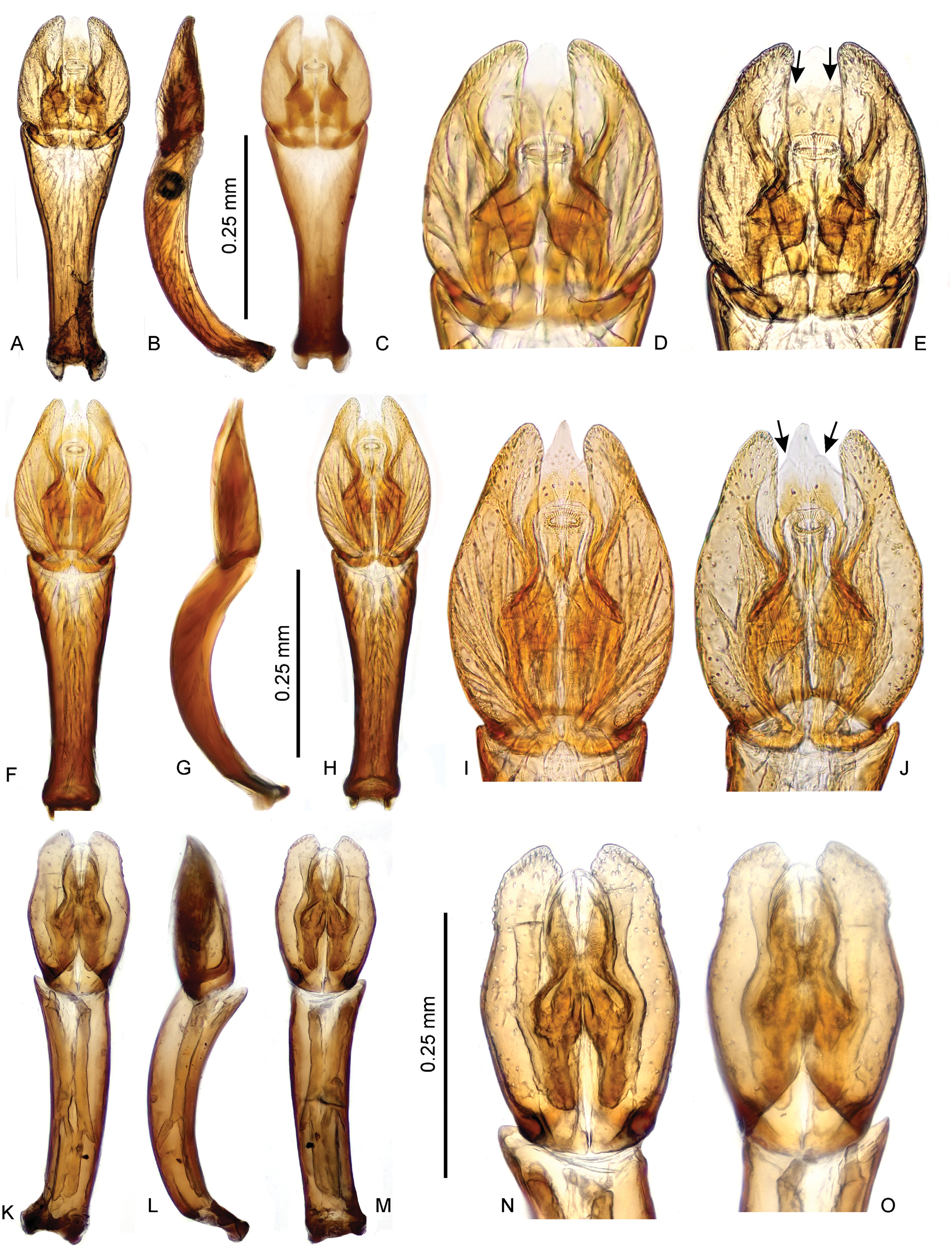

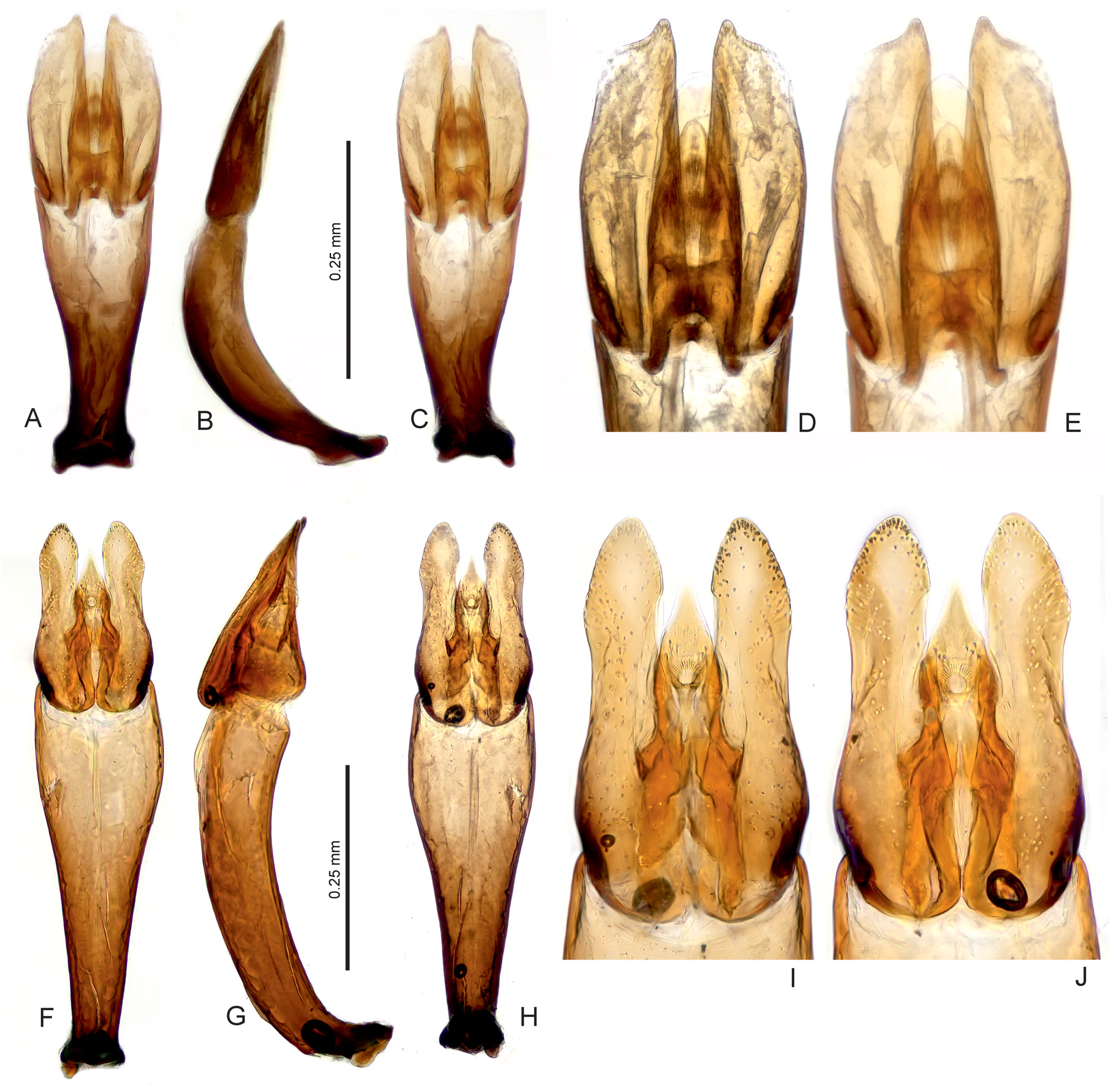

Characters important for species-level identification. All known species of Thysanarthria are very similar to each other in most external characters, and their tiny size makes the observation of many characters very difficult. The only external characters are (1) the presence/absence of the microsculpture on the head and labrum, pronotum and elytra, which can be either strongly mesh-like, weak and granulate, or totally absent; and (2) the body shape which can be wider ( Fig. 1A View Fig ) or more elongate ( Figs 1B, D View Fig ), but this is hard to compare in specimens which are not mounted in extended position on labels. Body coloration differs between species, with pronotum and elytra either uniformly yellowish ( Figs 1A, C View Fig ) or partly darkened (e.g. pronotum in Fig. 1D View Fig ) or uniformly dark brown ( Fig. 1B View Fig ). However, examination of longer series of some species ( T. championi and T. siamensis ) revealed that the coloration can vary within a species, and hence is not always reliable for identification. The same is true for the dorsal body microsculpture which seems to vary in intensity, at least in T. brittoni (see under that species). The body size also differs between species, and the presence of specimens of different size in the same series may indicate the presence of multiple species. However, in species in which more specimens were available, the body size was revealed to vary to some extent as well, and the body size can be hence used as an additional character only. Therefore, examination of the male genitalia is necessary for reliable identification in all cases. Ideally, the genitalia should be examined under a medium magnification of the compound microscope, and attention should be paid also to the membranous structures on the apical part of the median lobe (including short, paired, subapical projections which are present only in some species, e.g. Figs 5 View Fig D–E, I–J, 6 View Fig D–E, I–J). The proportions of parameres may be uneasy to observe as they are partly affected by the position of the aedeagus, and the genitalia should be carefully observed under slightly different angles in case of doubts. The ratio of paramere length to phallobase length should be evaluated in lateral view, due to the strongly bent phallobase in many species. The examination of the material used for this study shows that especially the form of the median lobe is constant and diagnostic, whereas the shape of parameres may slightly vary. The apex of the median lobe is membranous in many species, even though usually rather constant in shape, and it seems that at least in some species it can include parts which are normally inverted and hence not easy to observe, and may sometimes get fully everted after the treatment in KOH (which however may distort other parts of the aedeagus; see e.g. 4J and 7E which show fully everted apical membranous parts). Since the observation of this part is difficult, we did not consider it for species diagnosis.

As male genitalia are the only reliable character for species identification, below we provide detailed illustrations of the genitalia with which new specimens to be identified should be compared. Once the candidate species is found based on genital morphology, the external characters mentioned above (body size and coloration, presence/ absence of the microsculpture) should be compared with the (re)descriptions provided below. No identification key is hence provided.

Species groups. The limited number of characters makes it difficult to group the species into supposedly monophyletic species groups. Based on the genital morphology, the African Thysanarthria atriceps is very similar to the Arabian T. brittoni , and these two species seem to form a group of closely related species. The presence of subapical membranous lobes on the median lobe in T. brincki , T. bifida , T. cardamona , T. madurensis , and T. trifida ( Figs 5 View Fig D–E, I–J; 6 View Fig D–E, I–J; 8 View Fig N–O) may also point to a close relationships. Thysanarthria brincki and T. cardamona may form a clade within this group characterized by lateroapical spine on the paramere ( Figs 5 View Fig A–J).

Function of the abdominal gelatinous substance. All members of the tribe Chaetarthriini including Thysanarthria bear a series of long setae on the base of the abdomen which cover a shallow depression in ventrites 1–2 filled in by whitish gelatinous substance ( Figs 3 View Fig G–H). When submerged, Thysanarthria floats with dorsal body surface facing up, i.e. in the position usual for most other Hydrophilidae . The gelatinous substance hence does not serve to increase the buoyancy of the beetle as might be the case in the non-related genus Amphiops Erichson, 1843 which bears similar-looking gelatinous substance at the base of abdomen and is swimming in an upside-down position when submerged (Fikáček & Angus, pers. observ.). Moreover, the gelatinous substance does not interfere with the ventral air bubble of the submerged beetle: the bubble covers the whole ventral side of the beetle including the whole abdomen. Therefore, it seems that the substance cannot be functional in submerged beetle but may be an adaptation to its usual environment on the wet sand outside water. The gelatinous substance is sticky in alive specimens. Its function remains unknown.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Tribe |

Chaetarthriini |

Thysanarthria Orchymont, 1926

| Fikáček, Martin & Liu, Hsing-Che 2019 |

Chaetarthriomorphus

| HANSEN M. 1991: 126 |

| CHIESA A. 1967: 276 |

Thysanarthria Orchymont, 1926a:195

| ORCHYMONT A. 1926: 195 |

| REGIMBART M. 1903: 234 |