Pongo abelii, Lesson, 1827

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6700973 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6700569 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FA8785-400B-9F6A-FA87-FEE0F837B401 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Pongo abelii |

| status |

|

Sumatran Orangutan

French: Orang-outan de Sumatra / German: Sumatra-Orang-Utan / Spanish: Orangutan de Sumatra

Taxonomy. Pongo abelii Lesson, 1827 View in CoL ,

Indonesia, Sumatra.

This species is monotypic.

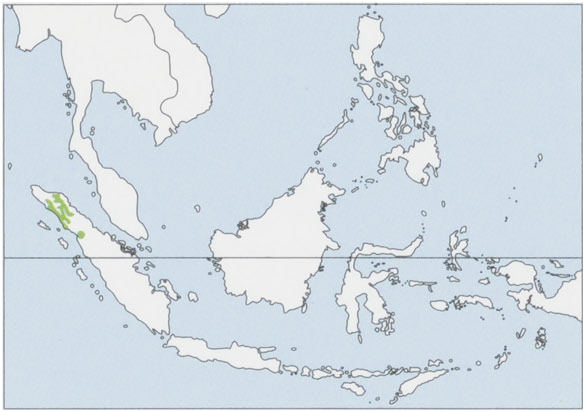

Distribution. NW Sumatra (Aceh & North Sumatra provinces). View Figure

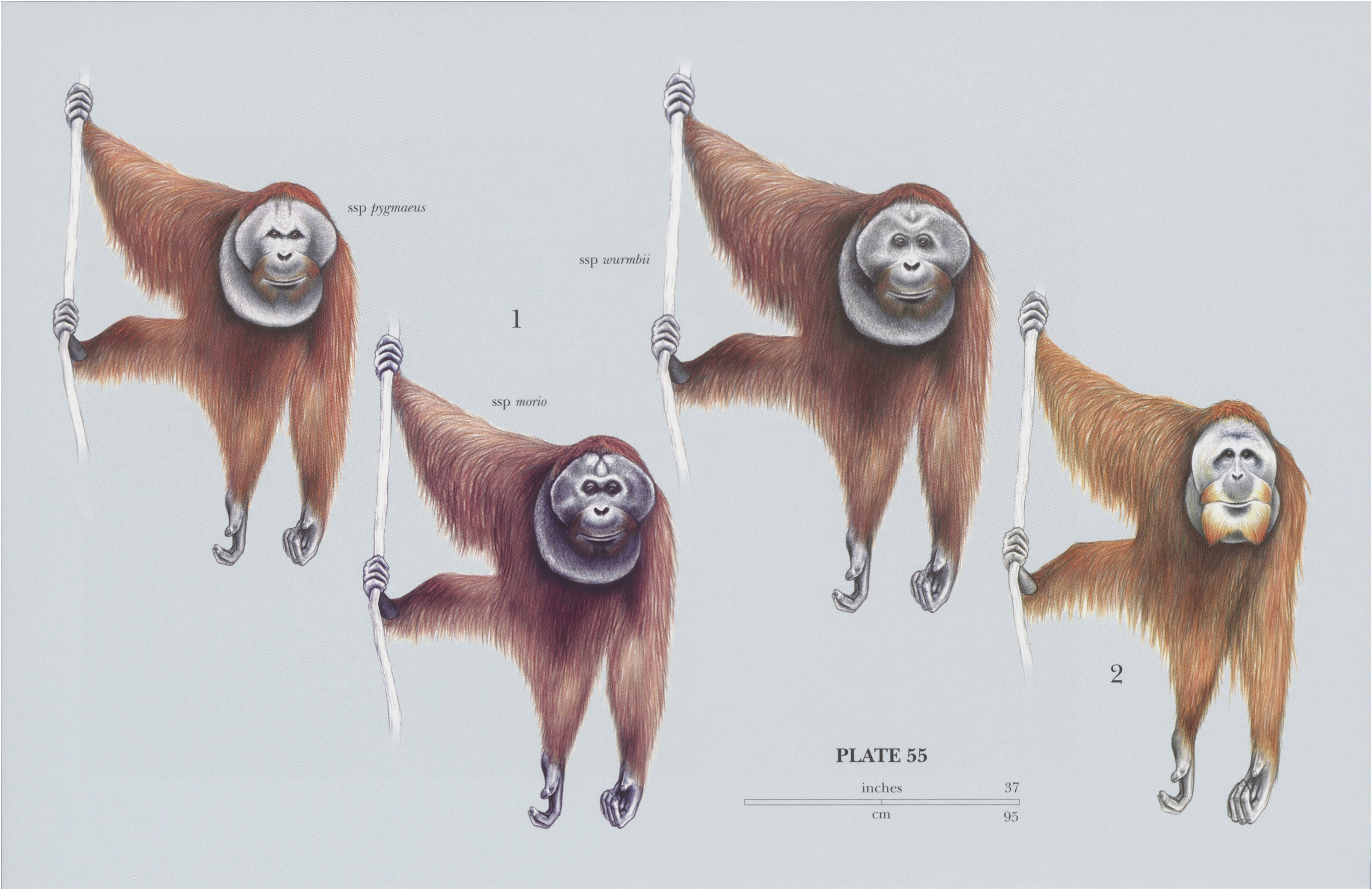

Descriptive notes. Head-body 94-99 cm (males) and 68-84 cm (females); weight 60-85 kg (flanged males), 30-65 kg (unflanged males), and 30-45 kg (females). The Sumatran Orangutan displays extreme sexual dimorphism. Males continue to get heavier as they get older and can reach 100 kg. Sumatran Orangutans are generally slightly slimmer and more linear in build than Bornean Orangutans ( Pongo pygmaeus ), and they have longer, paler, dense, and fleecy cinnamon-colored hair. Adult males have a pronounced luxuriant beard and mustache, and flanges that lie flat against the face and are thickly covered with fine white hairs, giving a wide appearance. Adult female Sumatran Orangutans also have well-developed beards.

Habitat. Primary lowland rainforest, swamp forest, and montane forest up to 1500 m above sea level, although elevations below 500 m are preferred. Densities of Sumatran Orangutans plummet by up to 60% with even low-intensity logging. Sumatran forests are highly productive due to Sumatra’s rich volcanic soils. Mast fruiting events occur, but fluctuations in food availability are less dramatic than on Borneo. These ecological conditions contribute to differences in behavior and life history between Sumatran and Bornean orangutans.

Food and Feeding. Sumatran Orangutans are primarily frugivorous, but they also eat young and mature leaves, seeds, shoots, bark, pith, flowers, eggs, soil, and invertebrates (termites and ants). Ripe succulent fruits are preferred; large fruits with hard husks are also eaten. They eat parts of up to 379 plant species, and up to 16 animal species have been recorded in their diets. Meat-eating has been observed (slow lorises, genus Nycticebus) but at very low frequency.

Breeding. Female Sumatran Orangutans give birth for the first time at c.15 years of age. Adult females have a menstrual cycle of 28-30 days. Females initiate and are the more active partner in consortships with adult males. A pair may consort for several days or weeks and copulate repeatedly. On average, a female bears 4-5 offspring during her lifetime. Sumatran Orangutans have the longest interbirth intervals (mean 9-3 years) of any mammalian species. After a gestation of c.254 days, a single infant is born. At birth, the infant’s abdomen is sparsely covered with hair, and the face is normally very wrinkled for the first few days. It clings to the ventral surface ofits mother until it is nearly one year old, and it may continue to ride on her back until 4-6 years of age. Sumatran Orangutans are weaned at c.7 years, although they remain in closely association with their mothers for 7-9 years. Adult male Sumatran Orangutans exhibit bimaturism. Dominant flanged males monopolize access to females in a localized area, and they are females’ preferred choice of mate. Females usually remain within hearing distance of a dominant flanged male. Unflanged males seem to arrest development of secondary sexually characteristics, such as flanges, in the presence of a clearly dominant male, and this suppression may last for many years. Unflanged male Sumatran Orangutans do not force females to copulate as often as unflanged male Bornean Orangutans do. Most pregnancies of Sumatran Orangutans are the result of females copulating willingly. Longevity is not known precisely, but wild Sumatran Orangutans have been estimated to reach ages of 58 years (male) and 53 years (female).

Activity patterns. Sumatran Orangutans are diurnal and almost exclusively arboreal, which may in part be due to the presence of Tigers (Panthera tigris) on Sumatra, which are known to prey on them. Large male Sumatran Orangutans occasionally travel short distances on the ground, but females virtually never come down from the forest canopy. Both sexes spend the early part of the day feeding, with a period of rest around midday, and resume feeding and traveling until the end of the day when they build a night nest. Sumatran Orangutans almost always make day nests during rest periods. Flanged males rest the most and travel the least of all age-sex classes.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Male and female Sumatran Orangutans live in home ranges with considerable overlap. Males travel more widely than females, over vast areas of forest, but the true extent of their home range size remains a mystery. Nevertheless,it has been inferred that males’ home ranges are several times larger than those of females. Flanged males advertise their location to females and other males by regularly emitting “long calls.” Males are generally solitary, females travel with their offspring, and adolescents of both sexes may form small groupsas they become increasingly independent oftheir mothers. Adult female Sumatran Orangutans in high-density populations in peat swamp regularly travel together for several days at a time. Average adult female feeding party size is 1-5-2 individuals, but up to 14 individuals have been observed feeding in the same large fruiting tree. The greater productivity of Sumatran forests allows Sumatran Orangutans to maintain a stable fruit diet, occupy large home ranges, and be more social than Bornean Orangutans. Sumatran Orangutans show cognitively complex and innovative behavior, including tool use, and have a larger repertoire of cultural behaviors than do Bornean Orangutans. In swamp forest, Sumatran Orangutans regularly make and use tools to eat honey or seeds of the fruits of the “cemengang” ( Neesia , Malvaceae ). High densities of Sumatran Orangutans in peat swamp forests (as many as 8 ind/km?) seem to provide more opportunities for social learning. Sumatran Orangutans have a slightly larger average brain size than Bornean Orangutans, which may be related to their greater sociality and more frugivorous diet.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Sumatran Orangutan is seriously threatened by logging (both legal and illegal), wholesale conversion of forest to agricultural land, especially oil palm plantations, and habitat fragmentation by road construction. Individuals are also hunted and kept illegally as pets, usually as a by-product of habitat conversion and conflict with farmers at the forest edge, which results in many orangutans being killed as pests. In the Batang Toru region, Sumatran Orangutans are still hunted in the forest. Increasing fragmentation may soon result in further subdivisions of the remaining populations. In some areas, the rate of loss during the 1990s was ¢.1000 orangutans/year, and the total population of Sumatran Orangutans is thought to have declined by more than 50% prior to 2000. In 2006, the total population remaining was estimated at 3500-12,000 individuals. A major stronghold is the 26,000 km* Leuser Ecosystem Conservation Area, which supports ¢.75% of the remaining Sumatran Orangutans and has the highest density populations in peat swamp forests on the western coast. It was created by a Presidential decree in 1998 that does not exclude non-forest uses but stresses the importance of sustainable management with conservation of natural resources as the primary goal. Also within the Leuser Ecosystem is the 9000 km* Gunung Leuser National Park, a mountainous area that supports ¢.25% of the remaining Sumatran Orangutans. Gunung Leuseris also a Man and Biosphere Reserve and part of the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of the Sumatra World Heritage Cluster Site. There are no other notable large conservation areas with Sumatran Orangutans outside the Leuser Ecosystem, but there is one more potentially viable population (c.600 individuals) in the Batang Toru forests, southwest of Lake Toba in North Sumatra. Efforts are underway to obtain protected status for this area, which is currently slated as a timber concession. Although Sumatran Orangutans themselves are strictly protected under Indonesian law, better legal protection of large areas of primary lowland forest is needed to secure their long-term future. A few small fragments of forest outside of the main blocks may still contain small numbers of Sumatran Orangutans, but these are not considered viable in the long term.

Bibliography. Hardus et al. (2012), Husson et al. (2009), Knott et al. (2009), Lyon (1908), Markham & Groves (1990), Marshall, Ancrenaz et al. (2009), Morrogh-Bernard et al. (2009), Napier & Napier (1967), van Noordwijk et al. (2009), Russon, van Schaik et al. (2009), Russon, Wich et al. (2009), van Schaik, Ancrenaz et al. (2003), van Schaik, van Noordwijk et al. (2009), Singleton et al. (2004), Taylor & van Schaik (2007), Utami-Atmoko & van Schaik (2010), Utami Atmoko et al. (2009), Wich, Singleton et al. (2003), Wich, Utami-Atmoko etal. (2006), Wich, Vogel et al. (2011), Wich, de Vries et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.