Anadenobolus monilicornis ( Porat, 1876 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5179429 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4B813563-87F1-4B98-8462-F14504D89E21 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FD87F7-FFBF-FFEB-FF7C-FD177D089AF5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Anadenobolus monilicornis ( Porat, 1876 ) |

| status |

|

Anadenobolus monilicornis ( Porat, 1876) View in CoL Figures 1–3 View Figures 1–3

Spirobolus monilicornis Porat, 1876: 31–32 . Pocock 1893: 123, 138; 1894: 499.

Spirobolus heilprini Bollman, 1889: 127 . Synonymized by Pocock (1893).

Spirobolus virescens Daday, 1891: 140 View in CoL , pl. 7, fig. 8–10. Synonymized by Pocock (1893).

Rhinocricus ramagei Pocock, 1894: 489 View in CoL . Chamberlin 1918: 180. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus grenadensis Pocock, 1894: 498–499 View in CoL , pl. 38, fig. 11. Chamberlin 1918: 196; 1922b: 7 (key). Loomis 1934: 15. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus monilicornis: Pocock 1894: 499–500 View in CoL . Chamberlin 1918: 200, 258 (table); 1920: 275; 1922b: 8 (key); 1923: 36; 1924: 43; 1947: 38; 1950: 140, fig. 7–8. Loomis 1934: 18; 1936: 62–63. Van der Drift 1963: 6–7, 32–33.

Rhinocricus consociatus Pocock, 1894: 500 View in CoL , pl. 38, fig. 7. Chamberlin 1918: 200; 1922b: 8 (key). Loomis 1934: 18. Synonymy suggested by Loomis (1934), formalized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus grammostictus Pocock, 1894: 501 View in CoL . Chamberlin 1918: 202; 1922b: 8 (key). Loomis 1934: 18–19, fig. 8. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus serpentinus Pocock, 1894: 501–502 View in CoL , pl. 38, fig. 9. Marek et al. 2003: 66. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus anguinus Pocock, 1894: 502–503 View in CoL . Chamberlin 1918: 201; 1922b: 8 (key). Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus leptopus Pocock, 1894: 503 View in CoL . Chamberlin 1918: 197; 1922b: 8 (key). Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus vincentii View in CoL (sic.) Pocock, 1894: 503–504, pl. 38, fig. 10. Chamberlin 1918: 202. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus chazaliei Brölemann, 1900: 93–94 View in CoL , pl. 6, fig. 8–13. Chamberlin 1918: 190. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus socius Chamberlin, 1918: 196 View in CoL ; 1922b: 7 (key). Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus juxtus Chamberlin, 1918: 200 View in CoL ; 1922b: 8 (key). Synonymy suggested by Loomis (1934), formalized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus tobagoensis Chamberlin, 1918: 201 View in CoL ; 1922b: 8 (key). Synonymy suggested by Loomis (1934), formalized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus mimeticus Chamberlin, 1918: 202 View in CoL ; 1922b: 8 (key). Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus vincenti: Chamberlin 1918: 202 View in CoL ; 1922b: 9 (key).

Rhinocricus ectus Chamberlin, 1920: 275–276 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 54. New Synonymy (implied by Jeekel [2009a]).

Rhinocricus limatulus Loomis, 1934: 14–15 View in CoL , fig. 5a–b. Synonymized by Jeekel (2009a).

Rhinocricus consociatus ecaudatus Loomis, 1934: 18 View in CoL . Synonymized by Hoffman (1999).

Cubobolus ramagei: Loomis 1934: 19–20 View in CoL , fig. 9a–c.

Eurhinocricus monilicornis: Schubart 1951: 239 .

Orthocricus serpentineus (sic.): Vélez 1963: 210.

Orthocricus monilicornis: Vélez 1963: 210 .

Orthocricus consociatus: Vélez 1963: 210 .

Orthocricus juxtus: Vélez 1963: 210 .

Orthocricus tobagoensis: Vélez 1963: 210 .

Anadenobolus View in CoL (?) monilicornis: Mauriès 1980: 1094 , fig. 52–54.

Anadenobolus anguinus: Hoffman 1999:76 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003:14.

Anadenobolus chazalei: Hoffman 1999: 78 . Marek et al. 2003: 16.

Anadenobolus consociatus: Hoffman 1999: 78–79 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 17. Jeekel 2009a, fig. 3J.

Anadenobolus grammostictus: Hoffman 1999: 80 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 18. Jeekel 2009a, fig. 3E.

Anadenobolus grenadensis: Hoffman 1999: 80 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 18. Jeekel 2009a, fig. 3K.

Anadenobolus juxtus: Hoffman 1999: 80–81 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 19.

Anadenobolus leptopus: Hoffman 1999: 81 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 20.

Anadenobolus monilicornis: Hoffman 1999: 82 View in CoL . Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001: 71. Marek et al. 2003: 21. Pérez-Gelabert 2008: 75. Jeekel 2009a: 57, fig. 1–2; 2009b: 21.

Anadenobolus ramagei: Hoffman 1999: 85 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 24. Jeekel 2009a, fig. 3F.

Anadenobolus socius: Hoffman 1999: 85 View in CoL . Marek et al. 2003: 25.

Anadenobolus vincenti: Hoffman 1999: 86 View in CoL . Jeekel 2009a, fig. 3I.

Eurhinocricus sp. Shelley and Edwards 2002: 271–272.

Anadenobolus vincentii View in CoL (sic.): Marek et al. 2003: 26.

Anadenobolus serpentinus: Jeekel 2009a , fig. 3G.

Type specimen. Male holotype ( SMNH) taken by an unknown collector on an unknown date prior to 1876 at an unspecified site in Brazil, which constitutes a generalized indication ( Jeekel 2009a). The species has not been subsequently recorded from this country, so all citations of Brazilian occurrence refer to Porat’s (1876) original account.

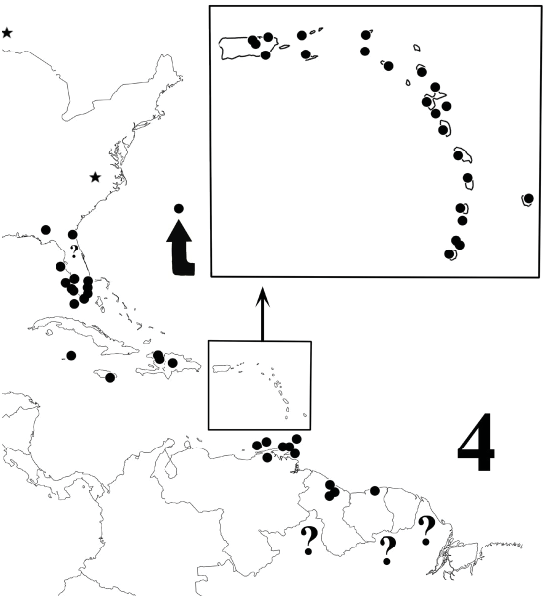

Diagnosis. A moderate-size, gonopodally variable species of Anadenobolus with ~45 rings, length ~ 45 mm, maximum width ~4.2 mm. Color black with variably yellowish to lime-green bands encircling caudal pleurotergal margins and anterior and caudal margins of collum. Epiproct ( Fig. 1 View Figures 1–3 ) variably long, apically rounded, overhanging and extending variably beyond paraproctal margins. Sternum of anterior gonopods ( Fig. 2 View Figures 1–3 ) variably subtriangular, broad basally and narrowing distad, sides often indented, with or without rounded medial lobe extending to around level of distal telopodital extremities, often terminating either slightly short of or beyond latter; telopodites apically rounded and uncinate. Posterior gonopods ( Fig. 2–3 View Figures 1–3 ) long, extending in situ well beyond distal extremities of anterior gonopod sternum/telopodites, usually protruding through pleurotergal aperture and visible externally; telopodites biramous, curving gently mediad, broad basally, narrow for most of length, flared distad; solenomeres arising from anteriomedial surfaces at varying positions distal to midlengths, extending ventromediad to or just beyond levels of tibiotarsal apices, subparallel to or overlapping latter, either sublinear, curving gently distad, or bisinuate; tibiotarsi continuing general telopodital curvatures, flared distad, dorsal corners varying from blunt and not extended to variably prolonged, acuminate, and even falcate.

Variation. The gonopods of Caribbean rhinocricids are less definitive of species than those of most regional diplopod families. Those of forms that do not seem conspecific with A. monilicornis because of more robust bodies and epiproctal differences closely resemble fig. 2–3, for example A. arboreus (Saussure, 1859) based on published illustrations ( Saussure 1860, pl. 4, fig. 28, 28a–d; Pocock 1894, pl. 38, fig. 4; Verhoeff 1941, fig. 14–16). If I had only the gonopods of A. arboreus , I would unhesitatingly equate them with A. monilicornis , but the different overall facies, more robust body, and short epiproct that does not overhang the paraprocts in some Puerto Rican individuals, appear to reflect another species. Consequently, A. monilicornis seems definable more by a combination of gonopodal and somatic traits than by the former alone, and contrasting the species with congeners is not currently possible. The most distinctive somatic feature is the blunt epiproct that overhangs and extends beyond the paraproctal margins ( Fig. 1 View Figures 1–3 ), either directly caudad or slanting ventrad. Jeekel (2009a) considered the epiproct’s shape a “minor detail,” and if so, A. monilicornis and all its synonyms could seemingly go under A. arboreus , the oldest name for an Antillean species. Perhaps there is indeed only one Caribbean species of Anadenobolus ; this possibility seems to warrant molecular investigation.

The variably subtriangular sternum dominates the anterior gonopods and terminates around the level of the telopodital apices, but may be slightly shorter or longer. It may be a virtually perfect triangle ( Jeekel 2009a, fig. 1), particularly in juveniles ( Pocock 1894, pl. 38, fig. 7, 11; Jeekel 2009a, fig. 3K), or the sides may bulge variably laterad at 1/3 length and/or be variably indented distad. If the latter concavity is substantial, the tip may be wider, appear swollen, and thus impart a “bottle-shaped” appearance to the overall structure. Every sternum exhibits aspects, some subtle, of these multiple variables, resulting in a confused and seemingly random melange of forms.

All posterior gonopod telopodites are long, slender, and curve smoothly and gently mediad; otherwise each is at least slightly different. Solenomeres may arise closer to the tibiotarsi than shown in fig. 3 and may be subequal in length to, or slightly shorter or longer than, the latter. Many are gently bisinuate ( Fig. 3 View Figures 1–3 ) and directed at nearly the same angles as, and lie subparallel to, the tibiotarsi; some, however, angle ventrad and overlie tibiotarsal apices. Breadths of tibiotarsal expansions vary as do their angles, though most resemble the condition in the holotype; the dorsal corners, moderately prolonged and acuminate in this male, may be short and blunt, more prolonged, filiform, gently curved, and even falcate.

Seemingly any condition in any of these structures may be found in any combination in any set of gonopods, and even males in the same sample can exhibit differences. Samples from numerous localities, particularly on different islands, present an inscrutable puzzle that understandably baffled early authors. I concur with Jeekel (2009a) that the most reasonable of the many possible anatomically-based resolutions is to consider all these variants conspecific and define A. monilicornis as encompassing the gamut of their conditions. To date, many nominal species have been based on minuscule or trivial features, like “blips” on tibiotarsal flares, that specialists would unquestioningly ignore in other orders and families as I believe should happen here. A similar situation seems to also exist in the Caribbean spirostreptid ( Spirostreptida ), Orthoporus antillanus ( Pocock, 1894) ( Krabbe and Enghoff 1984) .

Ecology. According to Mauriès (1980), A. monilicornis is common in more arid zones of Guadeloupe, but I have encountered individuals in Florida and St. Croix, US Virgin Islands, in moist spots and under virtually any object. Habitat notations on labels of new samples include “dead on floor in men’s gym shower,” “in mountain forest,” “under potted plant in nursery,” “under bricks and debris,” “in forest litter,” and “along fence bordering a nursery.” Characterizations of infestations in Florida include “inside, outside, everywhere including lights on ceilings” ( Shelley and Edwards 2002); “occurring in large numbers throughout historic and new buildings on property, climbing second story walls of historic stone house stairway”; “plentiful outside around house and sidewalk and getting inside”; “in mulch on ground”; and “severe infestation, thousands found on walls, floors, and ceilings, cannot walk in some rooms without stepping on them.”

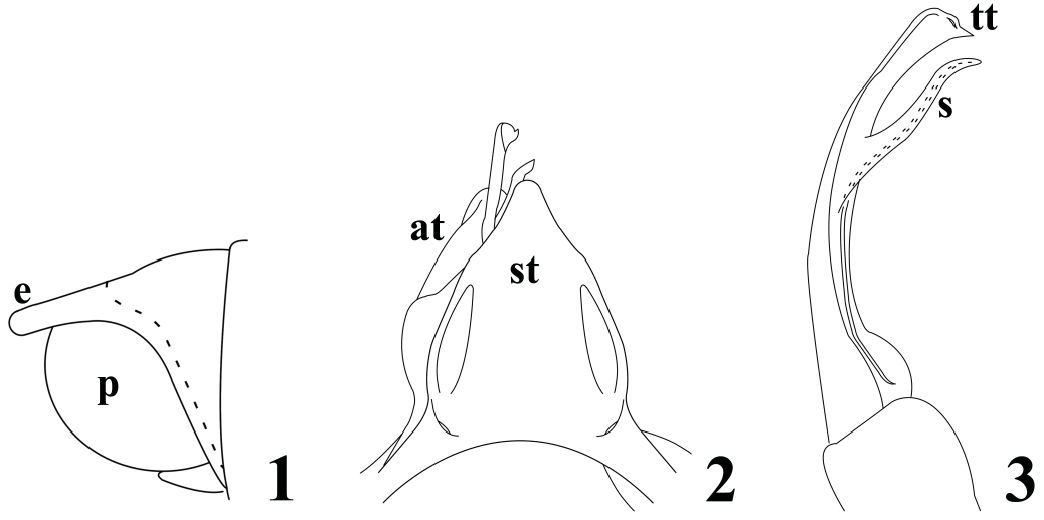

Distribution. Most of the Greater and Lesser Antilles derive from a long, curved terrane that rifted from northern coastal “proto-South America” at the interface of the Cretaceous Period (Mesozoic Era) and the Paleocene (Cenozoic) ( Smith et al. 1994, Shelley and Golovatch 2011, Shelley and Martinez-Torres 2013). The terrane drifted northward, rotated, and fragmented, and the progeny of the original diplopod inhabitants now occupy the insular remains. Because A. monilicornis occurs today from eastern coastal Venezuela to central Suriname ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ), we can reasonably conclude that ancestral forms inhabited the corresponding sector of the terrane and that remnants of this indigenous population were partitioned on, and hence native to, an unknown number of mostly southern Antillean islands. The abundance of A. monilicornis on fragments closest to South America – Trinidad, Tobago, and offshore Venezuelan islands – supports this hypothesis as does its apparent absence from Cuba (de la Torre y Callejas 1974, González Oliver and Golovatch 1990, Pérez-Asso 1998), deriving from the westernmost sector of the terrane, as the corresponding part of northern South America also lacks records.

Deciphering the true natural distribution of A. monilicornis is impossible. It is so readily spread by human activities that the distribution prior to discovery of the New World has surely been obliterated by repeated introductions; I doubt if purely indigenous populations still exist, their genomes having been diluted by the influx of exogenous ones. The populations in Florida, Bermuda, Barbados, and the Cayman Islands, which were not part of the Antillean terrane, are clearly adventive as is that on Jamaica, which is concentrated around Kingston, the island’s principal port and commercial center. However, ones on Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, the Lesser Antilles, and South America and associated islands probably include both native and adventive forms. The holotype is both the only type specimen ( Porat 1876) and the only Brazilian individual. Schubart never reported it from that country, but his gonopodal illustrations of the Brazilian species – Rhinocricus varians Brölemann, 1902 , and R. avanhandavae , R. serratulus , R. restingae , and R. bromelicola , all by Schubart (1951), resemble those in Fig. 2–3 View Figures 1–3 and may constitute additional synonyms.

Examining all relevant types and reported samples is well beyond my scope, so I accept all published localities and map them and new ones in Fig. 4 View Figure 4 . Jeekel (2009a) characterized A. monilicornis as a “widespread synanthrope in the West Indies and tropical South America,” but the only South American records are from eastern coastal Venezuela to central Surinam ; no evidence exists of adventive or native occurrences elsewhere in the continent, tropical or not. The milliped has not been recorded from the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Cuba, Central America , western Caribbean islands, and northwestern South America ; is absent from Colombia and western/central Venezuela; and no records exist from French Guiana despite plausible coastal occurrence around Cayenne. Anadenobolus monilicornis is spreading northward in Florida and now ranges from the southern peninsula through the arc of the Greater and Lesser Antilles (excepting Cuba but including Barbados) to Trinidad, offshore Venezuelan islands , and eastern coastal Venezuela to central Surinam, with outlier localities on Bermuda, the Florida panhandle, the Cayman Islands, and Jamaica. The plausible indigenous, “pre - Columbus,” range extends from Hispaniola and Puerto Rico through the Lesser Antillean Arc (excepting Barbados) to the same terminus .

Published Records. General Range Statements: “One of three or four rather widely distributed West Indian spirobolids, being recorded from six islands” ( Loomis 1936). “Widely distributed in Caribbean region, doubtless anthropochoric” ( Hoffman 1999). “At least from Hispaniola and Bermuda to Venezuela and Guyana ” and “described from Brazil, from where it was never recorded again” ( Jeekel 2009a).

Bermuda: Bermuda Islands in general ( Pocock 1893, 1894; Bollman 1889; Brölemann 1909; Chamberlin 1920, 1924, 1947; Schubart 1951; Mauriès 1980; Hoffman 1999; Marek et al. 2003; Jeekel 2009a). Hanging and Hungry Bays and Harrington Sound ( Chamberlin 1920, 1947). Nonsuch I. ( Chamberlin 1950).

Canada: Manitoba: Winnipeg, in base plate of palm plant (adventive) ( Shelley and Edwards 2002).

USA: Florida: Southern Florida in general, introduced. Broward Co., Ft. Lauderdale, Hugh Taylor Birch State Park ( Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007). Lee Co., Ft. Myers, Sanibel I. ( Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007). Liberty Co., Apalachicola Bluffs & Ravines Natural Preserve ( Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007). Miami-Dade Co., Coral Gables, Kendall, Matheson Hammock Park ( Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007). Monroe Co., Big Pine Key; Key Largo, Dagny Johnson Botanical Gardens; Tavernier, Plantation Key Nursery; Vaca Key, Marathon ( Shelley and Edwards 2002, Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007, Hribar 2010, Keller 2014). Orange/Seminole cos.,?Apopka ( Shelley and Edwards 2002). Palm Beach Co., Boca Raton ( Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007). Pinellas Co., no further locality ( Hollenbeck and Scuirorum 2007).

West Indies: West Indies in general ( Pocock 1893; Chamberlin, 1920, 1922b [key]; Jeekel 2009b). Antilles in general ( Brölemann 1909).

Cayman Islands: Little Cayman I., Bluff at Mary’s Bay ( Jeekel 2009a).

Greater Antilles: Hispaniola: Hispaniola in general ( Chamberlin 1918, Schubart 1951, Hoffman 1999, Pérez-Gelabert 2008). Haiti: Haiti in general ( Chamberlin 1924, Schubart 1951, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Jeekel 2009a). Cap Haitien ( Pocock 1894, Chamberlin 1918, Loomis 1936). Cap Haitien and Grand Riviere ( Chamberlin 1918, Loomis 1936). Bayeux and Limbé ( Loomis 1936).

Dominican Republic: Dominican Republic in general ( Mauriès 1980, Jeekel 2009a).

Puerto Rico: Puerto Rico in general ( Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001). Near Loiza, east of San Juan ( Jeekel 2009a).

Jamaica: Jamaica in general ( Hoffman 1999, Jeekel 2009a). Long Mountain, Mona Reservoir, University of the West Indies campus ( Jeekel 2009a).

Lesser Antilles: Antigua: Friars Hill, Parham Hill, Vernon Pond ( Jeekel 2009a).

Barbados: Barbados in general ( Pocock 1894; Chamberlin 1918, 1924; Schubart 1951; Hoffman 1999; Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001; Jeekel 2009a).

Baker’s Cave Gully, Cherry Tree Hill N of Belleplaine, escarpment S Codrington College, Hackleton’s Cliff at Horse Hill, N and NE of Holetown (Porter’s Gully and Wood), Oistins, Ridgeway Rock Hall, Spencer’s factory (E of Seawell Airport), St. George, Welchman Hall’s Gully ( Jeekel 2009a).

Dominica: Rouseau, Botanical Gardens ( Jeekel 2009a).

Grenada: Grenada in general ( Pocock 1894, Hoffman 1999, Jeekel 2009a). Grand Etang ( Chamberlin 1918, Loomis 1934, Hoffman 1999, Marek et al. 2003). Grand Anse ( Loomis 1934, Marek et al. 2003).

Grenadines: Grenadines in general ( Jeekel 2009a). Union I. ( Pocock 1894, Chamberlin 1918, Hoffman 1999, Marek et al. 2003). Bequia I. ( Loomis 1934). Carriacou I., Hillsborough ( Loomis 1934).

Guadeloupe: Guadeloupe in general ( Hoffman 1999, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Jeekel 2009a). Basse -Terre ( Mauriès 1980); St. Claude ( Loomis 1934). Grande - Terre ( Mauriès 1980); Moule, Usine Gardel, Ravine de Boisvin, near Cave d’Autre Bord ( Jeekel 2009a).

Les Saintes: Les Saintes in general ( Mauriès 1980, Jeekel 2009a). Terre -de -Haut I., Mare Basse ( Jeekel 2009a).

Los Testigos: Morro de la Iguana summit, Eastern slope of Morro Grande de Tamarindo ( Jeekel 2009a).

Margarita Island: Patio of Hotel Central in Porlamar, SE slope of Cerrio del Plache ( Jeekel 2009a).

Marie-Galante: Marie Galante in general ( Mauriès 1980, Jeekel 2009a). Falaise des Sources, Grelin, Ravine du Vieux Fort, Vangout ( Jeekel 2009a).

Martinique: Martinique in general ( Brölemann 1900, Chamberlin 1918, Loomis 1934, Schubart 1951, Hoffman 1999, Mauriès 1980, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Marek et al. 2003, Jeekel 2009a).

Saba: Saba in general ( Jeekel 2009a).

St. Kitts: East of Basseterre, Brimstone Hill Fortress National Park ( Jeekel 2009a).

St. Lucia: St. Lucia in general ( Pocock 1894, Chamberlin 1918, Hoffman 1999, Marek et al. 2003, Jeekel 2009a). Cul de Sac Valley, Bar de l’Isle above Castries ( Loomis 1934).

St Martin: St. Martin in general ( Loomis 1934, Schubart 1951, Mauriès 1980, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Jeekel 2009a). Colline Nettlé, La Croisade, Flagstaff, Meschrine Hill, Mildrum, Mornes Rouges, N of Copecoy Bay, Naked Boy Hill, near Pear Tree Hill east of Grand’Case, Pic du Paradis, St. Peter, west of Oysterpoint ( Jeekel 2009a).

St. Vincent: St. Vincent in general ( Pocock 1894, Chamberlin 1918, Hoffman 1999, Marek et al. 2003). Calliaqua Bay near Johnson Point ( Jeekel 2009a).

Trinidad and Tobago: Trinidad and Tobago in general ( Jeekel 2009a). Trinidad: Trinidad in general ( Daday 1891; Pocock 1893, 1894; Brölemann 1909; Chamberlin 1918; Loomis 1934; Schubart 1951; Hoffman 1999; Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001; Jeekel 2009a). Arima, Verdant Vale, St. Georges ( Chamberlin 1918, erroneously reported as being in Grenada as noted by Hoffman [1999]). Port of Spain, “Esperanza Sugar Estate” ( Chamberlin 1918). Chacachacare, Bande du Sud ( Jeekel 2009a). Tobago: Tobago in general ( Chamberlin 1924, Schubart 1951, Hoffman 1999, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Jeekel 2009a). Milford, Richmond, and King Bays; Plymouth ( Chamberlin 1918). Scarborough ( Chamberlin 1918, Jeekel 2009a). Store Bay ( Jeekel 2009a). Little Tobago I. ( Jeekel 2009a).

Virgin Islands: Virgin Islands in general ( Schubart 1951).

US Virgin Islands: St. Croix: St. Croix in general ( Chamberlin 1923, Schubart 1951, Jeekel 2009a). Canaän, Fredensborg Hill, Upper Bethlehem ( Jeekel 2009a).

South America: South America in general ( Chamberlin 1920, 1924). Northern South America in general ( Mauriès 1980). Northern coast of South America ( Jeekel 2009b).

Brazil: Brazil in general ( Porat 1876; Pocock 1893, 1894; Brölemann 1909; Schubart 1951, Mauriès 1980; Hoffman 1999; Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001; Marek et al. 2003; Jeekel 2009a).

Guianas: Guianas in general ( Hoffman 1999).

Guyana: Guyana in general ( Loomis 1936, Mauriès 1980, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Jeekel 2009a). Kartabo ( Chamberlin 1950, Schubart 1951). Labba Creek Sand Hills ( Chamberlin 1923, Schubart 1951). Georgetown ( Pocock 1894, Loomis 1934, Schubart 1951). Demerara ( Pocock 1893, 1894; Schubart 1951). East Trail along Demerara River ( Chamberlin 1923).

Suriname: Suriname in general ( Loomis 1936, Mauriès 1980, Pérez-Asso and Pérez-Gelabert 2001, Jeekel 2009a). Paramaribo ( Loomis 1934, Schubart 1951, Van der Drift 1963, Jeekel 2009b). Dirkshoop, Tambahredjo, Sidoredjo, Vank-kolonie ( Van der Drift 1963, Jeekel 2009b).

Venezuela: Caripito ( Chamberlin 1950, Schubart 1951, Jeekel 2009a).

New Records. Material from the following new localities was examined; missing data were not indicated on vial labels. When specimens were not sexed, the number of individuals in the sample is provided after the institutional acronym: FSCA, Florida State Collection of Arthropods, Gainesville; NCSM, North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh; NMNH, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

USA: Florida: Broward Co., Coconut Creek, 3600 W Sample Rd., Tradewinds Park, 11 October 2005, D. Benner (FSCA-1) and 4905 Cypress Ln., 29 August 2013, BA Danner, JE Hayden, J. Brambila (FSCA-1); Ft. Lauderdale, 24 SW 10 th St., 12 September 2006, L. Volpe (FSCA-3), 1729 NE 17 th Ave., 3 October 2009, S. Coleman (FSCA-3), and 2350 Delmar Pl., 24 September 2010, R. Carpenter (FSCA-2); Miramar, 11530 Interchange Cir., 23 April 2013, B. Jones (FSCA-1); and Weston, 3205 Hunter Rd., 22 April 2014, RA Martinez (FSCA-1). Collier Co., Naples, 6500 Airport Pulling Rd., Home Depot, 21 December 2010, SD Krueger (FSCA-2) and 5 April 2011, J. Brambila (FSCA-1), 4820 Bayshore Dr., Naples Botanical Garden, 13 March and 16 May 2012, J. Brambila, SD Krueger (FSCA-254), 1450 Merrihue Dr., Conservancy of SW Florida, 12 March 2012, J. Brambila, K. Relish (FSCA-14), 1590 Goodlette- Frank Rd., 14 March 2012, J. Brambila (FSCA-4), 6521 Livingston Woods Ln., 21 November 2013, SD Krueger (FSCA-4), and nursery on US hwy. 41 north, F, 14 January 2014, RM Shelley ( FSCA); and Marco Island, Olde Marco Village, Olde Marco Island Inn & Suites, 844 Palm St., 14 March 2012, J. Brambila (FSCA-6) and F, 16 January 2014, RM Shelley, J. Jewel ( FSCA). Lee Co., Pine Island, 2F, 5 August 1959 ( NMNH). Hillsborough Co., Tampa, 4509 N Habana Ave., 18 September 2012, B. McCauley (FSCA-1). Lee Co., Bokeelia, 7321 Howard Rd., Soaring Eagle Nursery, 25 April 2012, J. Brambila, RL Blaney (FSCA-10) and Ficus Tree Ln., 25 April 2012, DA Restom-Gaskill, J. Brambila, RL Blaney (FSCA-1); Ft. Myers, 10609 Avila Cir., 30 March 2012, JG Samuel (FSCA-1). Miami-Dade Co., Coral Gables, 60 Prospect Dr., 9 January 2003, K. Richardson (FSCA-3); Goulds, F, 5 February 2002, F. Hubbard ( FSCA) and 26 July 2002, S. Evans (FSCA-4); Homestead, 16870 SW 232 nd St., 31 May 2006, O. Garcia (FSCA-4); Miami, 10540 SW 126 th St., F, 26 February 2002, L. Nabutousky ( FSCA), Monkey Jungle, 14805 SW 216 th St., 8 August 2002, D. Hanna (FSCA-3), 16701 SW 72 nd Ave., Deering Estate, 8 September 2002, A. Warren-Bradley (FSCA-3) and 2 June 2005 and 22 March 2006, A. Warren-Bradley, AI Derksen (FSCA-15, 3), 11545 SW 107 th Ct., 11 December 2003, C. Dowling (FSCA-1), 3970 Kumquat Ave., 11 May 2004, R. Lawton (FSCA-4), 627 Sabal Palm Rd., 19 July 2004, K. Richardson (FSCA-1), 15765 NE 19 th Pl., 27 June 2006. M. François (FSCA-2), and 22301 SW 162 nd Ave., Castellow Hammock Park, 5 April 2011, S. Beidler (FSCA-1); Miami Gardens, 3340 NW 176 th St., 21 June 2012, B. Jones (FSCA-1) and North Miami, 13702 Biscayne Blvd., 13 December 2006, C. Pelegrin (FSCA-1). Monroe Co., Tavernier, Plantation Key Nursery, 20 March 2002, D. Moore (FSCA-15); Islamorada, Marker 88 – Oceanside, 24 July 2002, H. Glenn (FSCA-3). Nassau Co., Yulee, Agriculture Interdiction Sta. on highway I-95, 29 March 2012. AB Kalmbacher (FSCA-1). Pinellas Co., Clearwater, 13920 58 th St. N, 4 November 2009, MA Spearman (FSCA-2). North Carolina: Wake Co., Garner, F, 25 June 2005, RM Shelley ( NCSM).

Greater Antilles: Puerto Rico: Municipio do Morovis, 1 km (1.6 mi) N Torrecillas & 1 km (1.6 mi) SE Barahona, MM, FF, 30 March 1982, G. Morgan ( NCSM). Patillas, Las Casas de la Selva, M, 2 June 1989, HJ Scott ( NCSM).

Lesser Antilles: Barbados: Bathsheba, M, 3F, August 1967, NLH Kraus ( NMNH).

Saba: locality not specified, MM, FF, 2011, K. Wulf ( NCSM).

Trinidad and Tobago: Tobago: Northside Rd. at Bloody Bay, MM, FF, 28 May 1994, K. Auffenberg ( NCSM). Little Tobago I., above main western beach, 2M, 2F, 24 June 1994, K. Auffenberg ( NCSM). St.

Giles I., western promontory, M, 2F, 24 June 1994, K. Auffenberg ( NCSM). Trinidad: Guayaguayare Dist., Galeota Pt., 2M, 2 June 1994, K. Auffenberg ( NCSM).

US Virgin Islands: St. Croix: along hwy. 76 at St. Croix Gap, M, 8F, 3 July 1995, RM Shelley ( NCSM) ; and jct. hwys. 69 and 80, 3M, 3F, 4 July 1995, RM Shelley ( NCSM) . St. Thomas: Mountaintop, 13M, 4F, 14 August 1988, RM Shelley ( NCSM) New Island Record.

Three Adventive Populations: Florida: The introduction of Rhinocricidae to Florida is a rare instance when an invasion can be approximately timed and its progress monitored. The first encounter, in 1959, was a female on Pine Island, Lee Co., that did not lead to established populations there or on the peninsula proper. However, A. monilicornis was on the Keys in huge numbers in 2001; I visited Plantation Key Nursery in 2002, and while not openly evident, individuals were under every sizeable object on the ground. They have also been encountered at nurseries in Miami-Dade and Collier cos., are photographically documented online from Palm Beach and Pinellas cos., and a detached record exists from Liberty Co. in the eastern panhandle. Samples from the interior of south Florida are lacking, but in June 2014, some 13 years after the initial invasion, a subcontinuous population appears to exist in the south Florida Keys and northward along both coasts to at least the southern latitude of Lake Okeechobee.

Bermuda: The Bermuda islands lie east-southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, due east of Fripp Island, South Carolina, and ~ 1,600 km (1,000 mi) north of Puerto Rico, the closest Caribbean island harboring A. monilicornis . Lacking any contact ever with a Caribbean island, human agency seems the only plausible manner that A. monilicornis could reach Bermuda, since the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos, lying between it and Puerto Rico, would probably block rafting via ocean currents.

Barbados: Though considered part of the Lesser Antilles, Barbados lies in the Atlantic Ocean roughly 168 km (104 mi) east of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. It is composed primarily of coral reefs established atop sedimentation resulting from tectonic subduction. Barbados was not part of the Antillean terrane and has never directly contacted a Caribbean island. Human agency is plausibly responsible for most of its A. monilicornis population, though rafting may have contributed.

Remarks. Loomis (1934) reasoned that R. serpentinus was probably a valid species, but Jeekel (2009a) synonymized it under A. monilicornis .

The citation of Daday (1889) for Spirobolus virescens ( Marek et al. 2003) is incorrect; the account is actually in Daday (1891).

Monkeys at Monkey Jungle in Miami were observed rubbing A. monilicornis in their fur, presumably to acquire defensive secretions as a mosquito/insect repellant. Valderrama et al. (2000) noted this behavior among capuchin monkeys ( Cebus olivaceus ) with Orthoporus dorsovittatus (Verhoeff, 1938) ( Spirostreptida : Spirostreptidae ) in a central Venezuelan reserve as did Weldon et al. (2003) and Buden et al (2004) with both wild and captive capuchins. The active ingredients of O. dorsovittatus ’ secretions are benzoquinones, and whereas those of A. monilicornis are unknown, these compounds are present in rhinocricid secretions, as shown by Moussatché et al. (1969) for the Brazilian species, R. varians Brölemann, 1901 , and the Oceanian, Acladocricus setigerus (Silvestri, 1897) .

| SMNH |

Department of Paleozoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History |

| FSCA |

Florida State Collection of Arthropods, The Museum of Entomology |

| NCSM |

North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences |

| NMNH |

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History |

| R |

Departamento de Geologia, Universidad de Chile |

| US |

University of Stellenbosch |

| RM |

McGill University, Redpath Museum |

| MM |

University of Montpellier |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Anadenobolus monilicornis ( Porat, 1876 )

| Shelley, Rowland M. 2014 |

Anadenobolus vincentii

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 26 |

Eurhinocricus sp.

| Shelley, R. M. & G. B. Edwards 2002: 271 |

Anadenobolus anguinus:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 14 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 76 |

Anadenobolus chazalei:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 16 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 78 |

Anadenobolus consociatus:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 17 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 79 |

Anadenobolus grammostictus:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 18 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 80 |

Anadenobolus grenadensis:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 18 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 80 |

Anadenobolus juxtus:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 19 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 81 |

Anadenobolus leptopus:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 20 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 81 |

Anadenobolus monilicornis: Hoffman 1999: 82

| Jeekel, C. A. W. 2009: 57 |

| Perez-Gelabert, D. E. 2008: 75 |

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 21 |

| Perez-Asso, A. R. & D. E. Perez-Gelabert 2001: 71 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 82 |

Anadenobolus ramagei:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 24 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 85 |

Anadenobolus socius:

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 25 |

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 85 |

Anadenobolus vincenti:

| Hoffman, R. L. 1999: 86 |

Anadenobolus

| Mauries, J. - P. 1980: 1094 |

Orthocricus serpentineus

| Velez, M. J. 1963: 210 |

Orthocricus monilicornis: Vélez 1963: 210

| Velez, M. J. 1963: 210 |

Orthocricus consociatus: Vélez 1963: 210

| Velez, M. J. 1963: 210 |

Orthocricus juxtus: Vélez 1963: 210

| Velez, M. J. 1963: 210 |

Orthocricus tobagoensis: Vélez 1963: 210

| Velez, M. J. 1963: 210 |

Eurhinocricus monilicornis:

| Schubart, O. 1951: 239 |

Rhinocricus limatulus

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 15 |

Rhinocricus consociatus ecaudatus

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 18 |

Cubobolus ramagei:

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 20 |

Rhinocricus ectus

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 54 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1920: 276 |

Rhinocricus socius

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 7 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 196 |

Rhinocricus juxtus

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 200 |

Rhinocricus tobagoensis

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 201 |

Rhinocricus mimeticus

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 202 |

Rhinocricus vincenti:

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 9 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 202 |

Rhinocricus chazaliei Brölemann, 1900: 93–94

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 190 |

| Brolemann, H. W. 1900: 94 |

Rhinocricus ramagei

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 180 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 489 |

Rhinocricus grenadensis

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 15 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 7 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 196 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 499 |

Rhinocricus monilicornis:

| van der Drift, J. 1963: 6 |

| Loomis, H. F. 1936: 62 |

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 18 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 200 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 500 |

Rhinocricus consociatus

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 18 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 200 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 500 |

Rhinocricus grammostictus

| Loomis, H. F. 1934: 18 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 202 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 501 |

Rhinocricus serpentinus

| Marek, P. E. & J. E. Bond & P. Sierwald 2003: 66 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 502 |

Rhinocricus anguinus

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 201 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 503 |

Rhinocricus leptopus

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1922: 8 |

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 197 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 503 |

Rhinocricus vincentii

| Chamberlin, R. V. 1918: 202 |

| Pocock, R. I. 1894: 503 |

Spirobolus virescens

| Daday, J. 1891: 140 |

Spirobolus heilprini

| Bollman, C. H. 1889: 127 |

Spirobolus monilicornis

| Pocock, R. I. 1893: 123 |

| Porat, C. O. 1876: 32 |