Trilobatus quadrilobatus ( d’ Orbigny, 1846 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2019.1578831 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10932463 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/072AAD72-232A-AE69-38E2-FAE9FE38F6F0 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe (2024-03-26 20:12:52, last updated 2024-04-05 13:37:31) |

|

scientific name |

Trilobatus quadrilobatus ( d’ Orbigny, 1846 ) |

| status |

|

Trilobatus quadrilobatus ( d’ Orbigny, 1846) View in CoL

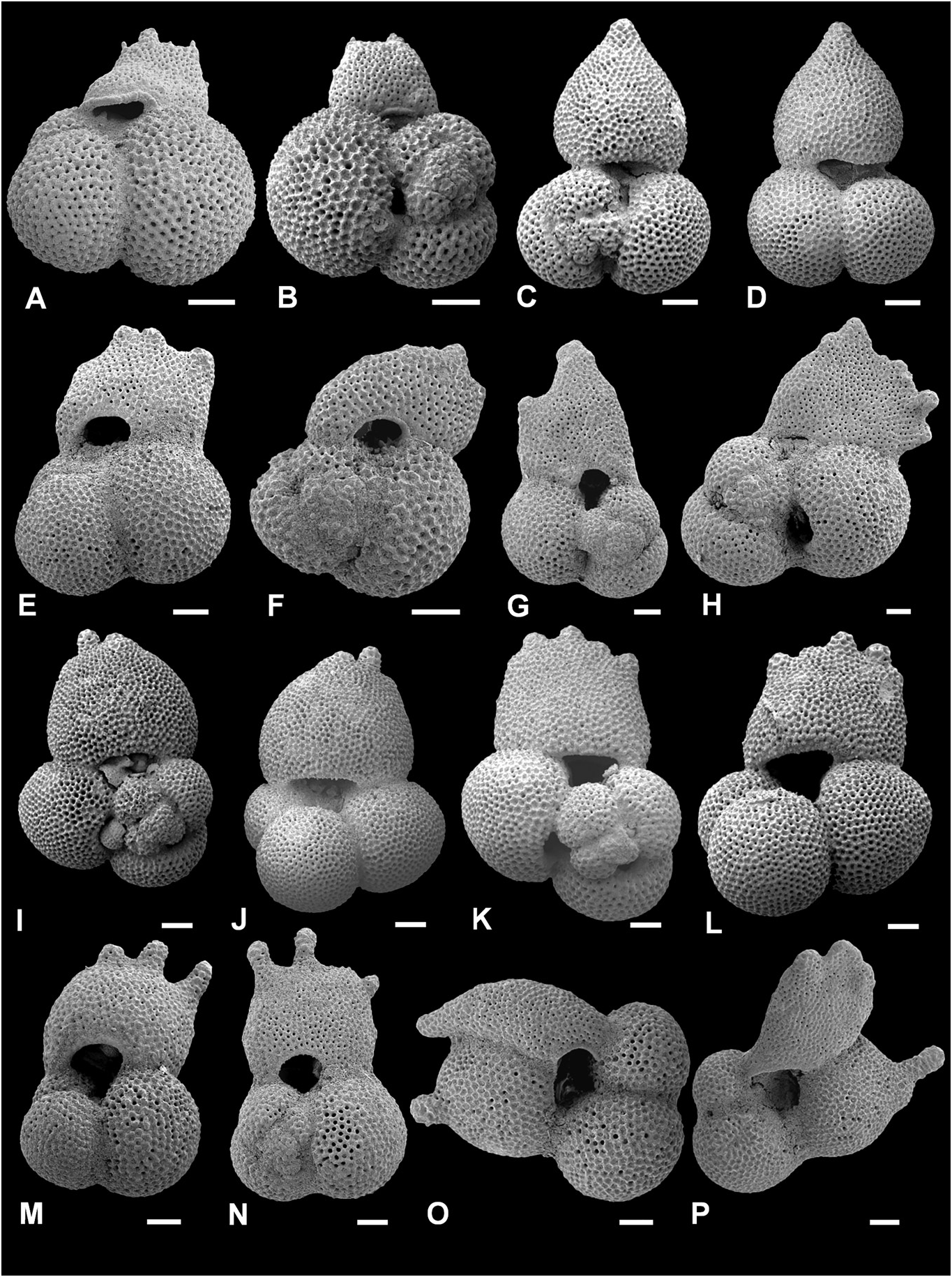

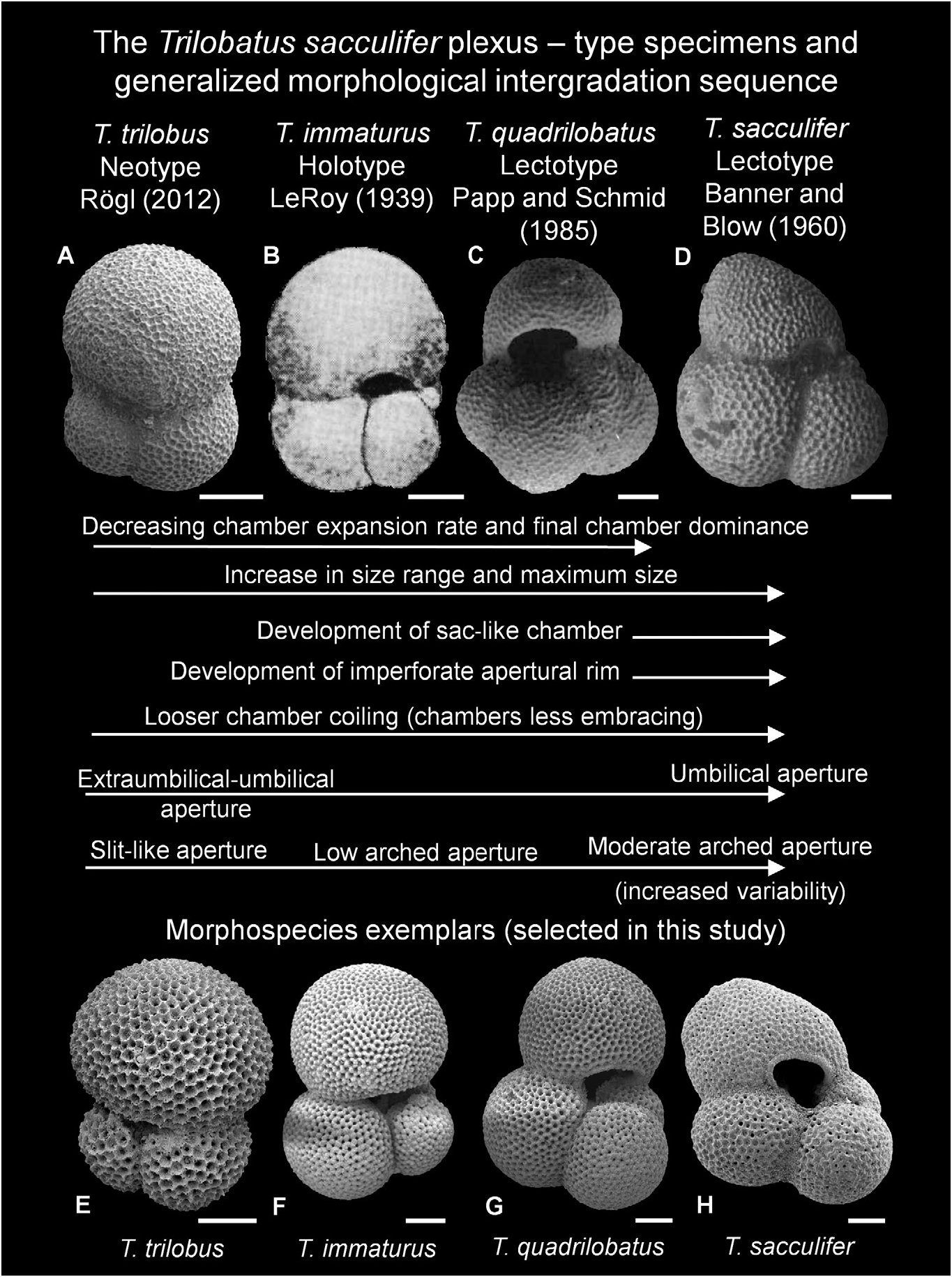

( Figs 7L–N View Figure 7 , 8A–K View Figure 8 , 15A, 17C, G View Figure 17 )

1846 Globigerina quadrilobata d’ Orbigny : 164, pl. 9, figs 7–10.

1960 Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (d’ Orbigny) ; Banner & Blow: 17, pl. 4, fig. 3a, b.

1983 Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (d’ Orbigny) ; Kennett & Srinivasan: 66, pl. 14, figs 1–3.

2003 Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (d’ Orbigny) ; Li, McGowran, & Brunner: 20, pl. P6, figs 16, 17.

2012 Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (d’ Orbigny) ; Rögl: 188, pl. 2, figs 3, 4.

2013 Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (d’ Orbigny) ; Fox & Wade: 400, fig. 11.4.

2018 Trilobatus quadrilobatus (d’ Orbigny) ; Spezzaferri, Olsson, & Hemleben: 296–298, pl. 9.12, figs 1–20.

Description. Type of wall: spinose, coarsely cancellate sacculifer - type wall texture.

Test morphology: low trochospire, 3.5 to typically 4 globose, near-spherical chambers in the final whorl increasing slowly-moderately in size as added; sutures distinct, depressed, straight to slightly curved on both sides; umbilicus narrow; primary aperture extraumbilical-umbilical or umbilical, generally a low arch, often broad, typically no bordering rim; prominent supplementary apertures on spiral side, one per chamber, placed at the sutures of the preceding chamber and third-previous chamber, occasionally only one visible due to infilling or secondary calcification.

Note: description is based on the original description and species concept of d’ Orbigny (1846, p. 164), and that of Banner & Blow (1960, pp. 17–19) and Kennett & Srinivasan (1983, p. 66), but is here emended.

Remarks. Trilobatus quadrilobatus is distinguished from T. sacculifer in possessing a globular, near-spherical final chamber as opposed to a sac-like final chamber. Trilobatus sacculifer also possesses a distinct lip bordering the primary aperture, whilst T. quadrilobatus has no lip (though gradation between the two morphospecies occurs). Trilobatus quadrilobatus also shows morphological gradation with T. immaturus , but differs in having a lower chamber expansion rate and a more open umbilicus and typically having four spherical chambers in the final whorl. Trilobatus quadrilobatus has a broad resemblance to the short-ranging Oligo–Miocene morphospecies Trilobatus primordius ( Blow & Banner 1962) , but T. primordius only possesses one supplementary aperture on the spiral side and may not have a strictly sacculifer - type wall texture (the original description of T. primordius by Blow & Banner [1962, p. 115] states it has a “markedly cancellate and punctate” surface).

Type locality. Nussdorf (= Nubdorf), Rara, Vienna Basin, Austria .

Taxonomic history. d’ Orbigny (1846) described Globigerina quadrilobata from the Vienna Basin, Austria. He noted that the final four chambers were of almost equal size, increasing only marginally in size as added ( d’ Orbigny 1846, p. 164). The original illustrations ( d’ Orbigny 1846, pl. 9, figs 7–10; also reproduced numerous times, e.g. in Papp & Schmid 1985, pl. 54, fig. 7 and Bolli & Saunders 1985, p. 193, fig. 20.18) clearly show this low chamber expansion rate in the final whorl. No supplementary apertures are visible in the illustrations or are recorded in the original description, although, as also discussed by Banner & Blow (1965), this omission does not preclude the possibility of supplementary apertures having been present on the specimen. Unfortunately, the original vial labelled ‘ G. quadrilobata ’, examined by Banner & Blow (1960) and later Papp & Schmid (1985), did not contain d’ Orbigny’ s (1846) figured specimen, but it was found to contain a suite of 11 specimens of at least three different morphospecies. According to Banner & Blow (1960), only five specimens were of the quadrilobate form. Despite multiple morphospecies being present, Banner & Blow (1960) reasoned that the contents of the vial were a suite of syntypic specimens for quadrilobata and designated a lectotype from one of the five quadrilobate forms. They assigned quadrilobata to Globigerinoides Cushman, 1927 .

Banner & Blow’ s (1960) record of the quadrilobata morphotype was almost its first reported occurrence in more than a century. Cushman (1946, p. 19) had found only one record of quadrilobata in the literature, noting that even this reported occurrence was probably not conspecific with d’ Orbigny’ s (1846) concept, and suggested that the name be “allowed to lapse”. The designation of a lectotype by Banner & Blow (1960) was described as a ‘resurrection’ by Todd (1961) and Jenkins (1966). Moreover, numerous authors disputed the validity of the presumed syntypic suite of specimens and thus the designated lectotype (e.g. Todd 1961; Bandy 1964a, b; Jenkins 1966, 1971; Bolli & Saunders 1985). The main arguments were threefold: (1) the contents of the vial, regardless of its label of ‘ G. quadrilobata ’, undoubtedly contained multiple morphospecies and should not have been considered syntypic despite containing ‘quadrilobate’ specimens; (2) the designated lectotype was not wholly consistent with d’ Orbigny’ s original (and sparse) concept (nor indeed were any of the 11 specimens). Bandy (1964a, b) referred quadrilobata back to the genus Globigerina primarily because d’ Orbigny’ s concept did not specify any supplementary apertures; and (3) numerous specimens apparently consistent with d’ Orbigny’ s original concept (i.e. not the concept of Banner & Blow) were apparently found in samples from the type locality (e.g. Bandy 1964b).

In two subsequent publications, Banner & Blow (1962, 1965) endeavoured to vindicate their lectotype selection, and considered their quadrilobata morphotype to be an evolutionarily ‘central form’, giving rise to both T. trilobus and T. sacculifer . This is of importance because most authors, contrarily, consider T. trilobus to be the more ‘primitive’ form, giving rise to T. quadrilobatus (e.g. Kennett & Srinivasan 1983). Other workers (e.g. Fleisher 1974, p. 1023) noted that the lectotype was probably not conspecific with the original concept, but argued it should be retained because of the wide prior usage. Chaproniere (1981, p. 110) also argued in favour of quadrilobatus and Banner & Blow’ s (1960, 1965) concept, and distinguished between trilobus , immaturus and quadrilobatus as separate subspecies of Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (i.e. a trinomial nomenclature with quadrilobatus as the central species). He also considered numerous other morphospecies to be subspecies of G. quadrilobatus that are here not in accordance with our definition of the plexus ( Chaproniere 1981).

To add further complication, Banner & Blow’ s (1960) lectotype was apparently lost and is therefore not available for examination. Papp & Schmid (1985) designated a replacement lectotype from the remaining material of the original vial, choosing a broadly similar specimen to the first lectotype. The validity of this lectotype might be disputed for the same aforementioned reasons. Despite the questionable lectotype selection(s), and rejection by other workers, the Banner & Blow (1960, 1965) concept of quadrilobatus has been used consistently since its inception.

Ultimately, the proliferation of the name quadrilobatus can be attributed to the taxonomic authority of Banner and Blow, and that Kennett & Srinivasan (1983) considered quadrilobatus a distinct morphospecies to trilobus , immaturus and sacculifer in their taxonomic atlas of Neogene planktonic foraminifera. Their influential work has been extensively used as the foremost taxonomic authority for Neogene planktonic foraminifera for more than 30 years. They posited a lineage of trilobus - immaturus - quadrilobatus - sacculifer . Many populations (fossil and Recent) contain a 3.5–4-chambered form that is not consistent with the species concepts of trilobus , immaturus or sacculifer ; such a morphotype is often called quadrilobatus .

Spezzaferri et al. (2015) recently reinvigorated this debate in their investigation into the polyphyletic genus Globigerinoides . As the lectotype of Papp & Schmid (1985) possesses a relatively high-arched aperture and a difficult-to-ascertain wall texture, Spezzaferri et al. (2015) placed it in the ‘ ruber group’ (i.e. in Globigerinoides ), rather than in new genus Trilobatus , where the rest of the sacculifer plexus ( T. trilobus , T. immaturus and T. sacculifer ) morphospecies were re-assigned. Placing the quadrilobatus lectotype in Globigerinoides rather than Trilobatus effected a radical change to the species concept because quadrilobatus had been consistently associated with the T. sacculifer plexus in most works since Banner & Blow (1960). A key problem is that the lectotype specimen of Papp & Schmid (1985) does not adequately exemplify the morphospecies concept of quadrilobatus used by most authors (i.e. the concept of Banner and Blow [1960, 1965] and Kennett & Srinivasan [1983]). Spezzaferri et al. (2015) stated that the lectotype does not have a sacculifer -type wall texture, yet this is considered one of the diagnostic characters for the whole T. sacculifer plexus (e.g. Banner & Blow 1960, 1965; Kennett & Srinivasan 1983). The illustrated lectotype in Papp & Schmid (1985) is not exceptionally preserved and the wall texture is somewhat ambiguous. It appears from the SEM reproduction in Figure 17 View Figure 17 to have variable wall texture, and in a re-examination of the specimen, evidence of a sacculifer -type texture has been identified in quadrilobatus ( Spezzaferri et al. 2018) , thus re-aligning quadrilobatus with the T. sacculifer plexus. It is of note that other specimens with a quadrilobatus morphology clearly show a markedly cancellate, sacculifer - type texture (e.g. Stewart et al. 2004, pl. 1, fig. E [exceptionally preserved Tanzanian specimen]; Rogl 2012, pl. 3, fig. 6).

An additional minor factor to consider is that the generally larger size of T. sacculifer and T. quadrilobatus compared to T. immaturus and T. trilobus means that the T. quadrilobatus and T. sacculifer wall textures may appear less coarsely cancellate than those of T. immaturus and T. trilobus . We provide further evidence for a cancellate, sacculifer - type wall texture for T. quadrilobatus ( Figs 7N View Figure 7 , 8B View Figure 8 ), confirming its place within Trilobatus .

It appears that the lectotype specimen selected by Papp & Schmid (1985) may not have been a ‘typical’ quadrilobatus morphotype based on the widely used concept from Kennett & Srinivasan (1983). We agree with previous authors ( Todd 1961; Bandy 1964a, b; Jenkins 1966; Fleisher 1974; Bolli & Saunders 1985) that the lectotype of Banner & Blow (1960) and replacement lectotype of Papp & Schmid (1985) for quadrilobatus may not have been conspecific with d’ Orbigny’ s (1846) original (and sparse) concept. However, it is also evident from our observations and those of other workers (e.g. Stewart et al. 2004; Rogl 2012) that a 3.5–4-chambered morphotype with a sacculifer -type wall texture exists. This morphotype is not consistent with the T. trilobus , T. immaturus or T. sacculifer descriptions and concepts, yet clearly intergrades with these other plexus members and is closely related. We consider this morphotype to be T. quadrilobatus ( Figs 7L–N View Figure 7 , 8A–K View Figure 8 ). We therefore follow Spezzaferri et al. (2018) and refer the quadrilobatus morphospecies (i.e. the concept of Kennett & Srinivasan [1983], and that of this study) to the new genus Trilobatus .

The SEM illustrations highlight the intergradation between both T. immaturus - T. quadrilobatus and T. quadrilobatus - T. sacculifer . For example, the T. quadrilobatus specimen in Figure 7L–N View Figure 7 is intermediate between T. immaturus and T. quadrilobatus sensu stricto, as it has a relatively high chamber expansion rate in the final whorl compared to T. quadrilobatus sensu stricto ( Fig. 8A–G View Figure 8 ). However, the prominence of the fourth chamber as well as the larger size is used to distinguish it from T. immaturus . As the forms intergrade, this delimitation is arbitrary, but through using a combination of chamber expansion rate, prominence of fourth chamber, size, and similarity to our suggested morphospecies exemplars (see Fig. 17 View Figure 17 ) it is possible to delimit T. immaturus and T. quadrilobatus .

The transition between T. quadrilobatus and T. sacculifer is illustrated in Figure 8 View Figure 8 . The forms in Figure 8A–G View Figure 8 are considered the morphospecies exemplars for T. quadrilobatus , whilst Figure 8H–P View Figure 8 show progressive flattening and extension of the final chamber. The specimens in Figure 8H–K View Figure 8 do not show significant flattening of the final chamber and are regarded as T. quadrilobatus , whereas Figure 8L–P View Figure 8 are considered to have final chamber flattened enough to be T. sacculifer (and Fig. 8P View Figure 8 is considered T. sacculifer sensu stricto). There is also a tendency towards higher arched primary apertures and the development of a bordering imperforate lip. Although some T. quadrilobatus specimens also possess an imperforate lip (e.g. Fig. 8F View Figure 8 ), it is infrequent. In contrast, almost all T. sacculifer specimens possess a prominent lip (it is a defining character), and even regularly possess a lip on the first supplementary aperture on the spiral side as well ( Figs 9B View Figure 9 , 10C View Figure 10 , 11B, F View Figure 11 ).

Bandy, O. L. 1964 a. Cenozoic planktonic foraminiferal zonation. Micropaleontology, 10, 1 - 17.

Bandy, O. L. 1964 b. The type of Globigerina quadrilobata d' Orbigny. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 15, 36 - 37.

Banner, F. T. & Blow, W. H. 1960. Some primary types of species belonging to the superfamily Globigerinaceae. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 11, 1 - 41.

Banner, F. T. & Blow, W. H. 1962. The type specimens of Globigerina quadrilobata d' Orbigny, Globigerina sacculifera Brady, Rotalina cultrata d' Orbigny and Rotalia menardii Parker, Jones and Brady. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 13, 98 - 99.

Banner, F. T. & Blow, W. H. 1965. Globigerinoides quadrilobatus (d' Orbigny) and related forms: their

Bolli, H. M. & Saunders, J. B. 1985. Oligocene to Holocene low latitude planktic foraminifera. Pp. 155 - 262 in H. M. Bolli, J. B. Saunders & K. Perch-Nielsen (eds) Plankton stratigraphy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Brady, H. B. 1877. Supplementary note on the Foraminifera of the Chalk (?) of the New Britain Group. Geological Magazine, New Series, Decade 2, 4, 534 - 536.

Chaproniere, G. C. H. 1981. Late Oligocene to early Miocene planktic Foraminiferida from Ashmore Reef No. 1 Well, northwest Australia. Alcheringa, 5, 103 - 131.

Cushman, J. A. 1927. An outline of the re-classification of the foraminifera. Contributions from the Cushman Laboratory for Foraminiferal Research, 3, 1 - 105.

Cushman, J. A. 1946. The species of Globigerina described between 1839 and 1850. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 22, 15 - 21.

d' Orbigny, A. 1846. Foraminif`eres fossils du Bassin tertiaire de Vienne (Autriche). Gide et Comp, Paris, 312 pp.

Fleisher, R. L. 1974. Cenozoic planktonic foraminifera and biostratigraphy, Arabian Sea, Deep Sea Drilling Project, Leg 23 A. Pp. 1001 - 1072 in R. B. Whitmarsh, O. E. Weser, D. A. Ross, S. Ali, J. E. Boudreaux, R. L. Fleisher, D. Jipa, R. B. Kidd, T. K. Mallik, A. Matter, C. Nigrini, H. N. Siddiquie & P. Stoffers (eds) Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 23.

Jenkins, D. G. 1966. Planktonic foraminifera from the type Aquitanian - Burdigalian of France. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 17, 1 - 15.

Jenkins, D. G. 1971. New Zealand Cenozoic planktonic foraminifera. New Zealand Geological Survey Paleontological Bulletin, 42, 1 - 278.

Kennett, J. P. & Srinivasan, M. S. 1983. Neogene planktonic Foraminifera, a phylogenetic atlas. Hutchinson Ross, Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, 265 pp.

Papp, A. & Schmid, M. E. 1985. Die fossilen Foraminiferen des terti ¨ aren Beckens von Wien: Revision der Monographie von Alcide d' Orbigny (1846). Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 37, 1 - 311.

Schubert, R. J. 1910. Uber ¨ Foraminiferen und einen Fischotolithen aus dem fossilen Globigerinenschlamm von Neu-Guinea. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Koniglichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt, 14, 318 - 328.

Spezzaferri, S., Kucera, M., Pearson, P. N., Wade, B. S., Rappo, S., Poole, C. R., Morard, R. & Stalder, C. 2015. Fossil and genetic evidence for the polyphyletic nature of the planktonic Foraminifera ' Globigerinoides ', and description of the new genus Trilobatus. PLoS ONE, 10, e 0128108.

Spezzaferri, S., Olsson, R. K. & Hemleben, C. 2018. Taxonomy, biostratigraphy, and phylogeny of Oligocene to lower Miocene Globigerinoides and Trilobatus. Pp. 269 - 306 in B. S. Wade, R. K. Olsson, P. N. Pearson, B. T. Huber & W. A. Berggren (eds) Atlas of Oligocene Planktonic Foraminifera. Cushman Foundation of Foraminiferal Research, Special Publication, 46.

Stewart, D. R. M., Pearson, P. N., Ditchfield, P. W. & Singano, J. M. 2004. Miocene tropical Indian Ocean temperatures: evidence from three exceptionally preserved foraminiferal assemblages from Tanzania. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 40, 173 - 189.

Todd, R. 1961. On selection of lectotypes and neotypes. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 12, 121 - 122.

Figure 7. Typical Trilobatus immaturus and intergradation with Trilobatus quadrilobatus. A–K, Trilobatus immaturus (LeRoy, 1939); L–N, Trilobatus quadrilobatus (d’Orbigny, 1846). A–C, I–K, ODP Site 926, Ceara Rise, western tropical Atlantic, 11H/04/ 50–52 cm (A, B, umbilical view; C, detail wall texture and infilled pores; I, spiral view; J, detail of final chamber wall texture; compare with K, detail of penultimate chamber where primary wall texture is obscured by thick gametogenic calcite); D–H, GLOW- 3, south-west Indian Ocean (D, detail of wall texture and imperforate lip on first supplementary aperture; E, H, umbilical view; F, G, spiral view). L–N, GLOW-3, south-west Indian Ocean (L, spiral view; M, umbilical view; N, detail of wall texture including clear spine holes). Scale bars = 100Lm, except for close-up images C, D, J, K, N, where scale bars = 20 Lm.

Figure 8. Typical Trilobatus quadrilobatus and intergradation with Trilobatus sacculifer. A–K, Trilobatus quadrilobatus (d’Orbigny, 1846); L–P, Trilobatus sacculifer (Brady, 1877). A, B, E, F, G–K, ODP Site 871, Limalok Guyot, Marshall Islands, equatorial Pacific 3H/03/60–62 cm (A, E–I, K, umbilical view; B, detail of wall texture, including spine holes, infilled pores, broadened interpore ridges; J, detail of wall texture and imperforate lip developed on primary aperture); C, D, GLOW-3, south-west Indian Ocean (C, umbilical view; D, spiral view). L–P, ODP Site 871, Limalok Guyot, Marshall Islands, equatorial Pacific 3H/03/60–62 cm (L–P, umbilical view; for L note slight chamber flattening compared with I–K). Scale bars = 100 Lm, except for close-up images B and J, where scale bars = 20 Lm.

Figure 9. Morphological variation in the final sac-like chamber(s) of Trilobatus sacculifer (Brady, 1877). A–G, I, ODP Site 1115, Woodlark Basin, western Pacific; 11H/04/25–27 cm (A, B, I, spiral view, in A note elongated sac-like chamber; C–G, umbilical view, in D note kummerform sac-like chamber, in F note large, asymmetrical aperture with surrounding imperforate area); H, J–P, ODP Site 871, Limalok Guyot, Marshall Islands, equatorial Pacific 3H/03/60–62cm (H, J–N umbilical view, in J note lobate sac-like chamber, in K note kummerform sac-like chamber, in L–N note two sac-like chambers; O, P, spiral view; note three sac-like chambers); Q, R, GLOW-3, south-west Indian Ocean (cross sectional view of wall, showing relict spines embedded within wall and chamber layers). Scale bars: A–P = 100 Lm; Q, R = 20 Lm.

Figure 10. Incipient protuberance development in Pleistocene to modern Trilobatus sacculifer. A–L, GLOW-3, south-west Indian Ocean (A, D, F, J, spiral view; B, E, G, K, umbilical view), in B note lobate sac-like chamber, in E note thin final sac-like chamber with different wall texture appearance relative to rest of test; C; detail of wall texture including spine holes; H, detail of two incipient protuberances; I, contrasting wall texture appearance in thinner final sac-like chamber with smooth topography, and penultimate chamber with well-developed sacculifer-like texture and spine holes; L, detail of wall texture showing raised spine bases); M, Barbados, Caribbean Sea, specimen cultured after plankton net collection (umbilical view; reproduced from Brummer et al. 1987, pl. 1, fig. 14); N, Barbados, Caribbean Sea, specimen cultured after SCUBA dive collection (umbilical view; reproduced from B́e et al. 1982, fig. 12); O, P, Barbados, Caribbean Sea, specimens cultured after SCUBA dive collection (umbilical view; note multiple incipient protuberances; reproduced from of Hemleben et al. 1987, pl. 2, figs 11, 12). Scale bars = 100 Lm, except close-up images (I–L) where scale bars = 20Lm.

Figure 11. Trilobatus sacculifer with incipient protuberances and intergradation with Globigerinoidesella fistulosa. A–J, Trilobatus sacculifer (Brady, 1877); K–P, Globigerinoidesella fistulosa (Schubert, 1910). A–J, ODP Site 1115, Woodlark Basin, western Pacific; 10H/04/127–129cm (A, D, J, umbilical view, in A note kummerform final sac-like chamber; B, C, H, I, spiral view, in B note kummerform final sac-like chamber); E–G, ODP Site 1115, Woodlark Basin, western Pacific; 11H/04/25–27cm (E, umbilical view; F, G, spiral view). K, L, O, P, ODP Site 1115, Woodlark Basin, western Pacific; 10H/04/127–129 cm (K, spiral view; L, umbilical view; note multiple small protuberances and broad flattened final chamber; O, P, umbilical view); M, N, ODP Site 1115, Woodlark Basin, western Pacific; 11H/04/25–27 cm (umbilical view). Scale bars = 100 Lm.

Figure 17. Trilobatus sacculifer plexus, showing type specimens (A–D), morphological intergradation sequence and morphospecies exemplars (E–H). A, E, Trilobatus trilobus (Reuss, 1850); B, F, Trilobatus immaturus (LeRoy, 1939); C, G, Trilobatus quadrilobatus (d’Orbigny, 1846); D, H, Trilobatus sacculifer (Brady, 1877). A, salt mine Wieliczka, near Krakow, Poland (umbilical view; neotype image reproduced from Rogl 2012, pl. 1, fig. 1). B, Telisa Shales, Tapoeng Kiri area, Rokan-Tapanoeli, Central Sumatra, Indonesia (umbilical view; holotype image reproduced from LeRoy 1939, pl. 3, fig. 19). C, Nussdorf (= Nubdorf), Rara, Vienna Basin, Austria (umbilical view; lectotype image reproduced from Papp & Schmid 1985, pl. 3, fig. 19). D, New Ireland, Papua New Guinea (umbilical view; lectotype of Banner & Blow 1960, image reproduced from Williams et al. 2006, pl. 1, fig. 1). E, GLOW-3, south-west Indian Ocean (umbilical view). F, ODP Site 871, Limalok Guyot, Marshall Islands, equatorial Pacific 3H/ 03/60–62cm (umbilical view). G, ODP Site 871, Limalok Guyot, Marshall Islands, equatorial Pacific 3H/03/60–62 cm (umbilical view). H, ODP Site 1115, Woodlark Basin, western Pacific; 11H/04/25–27 cm (umbilical view). Scale bars = 100 Lm.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

1 (by felipe, 2024-03-26 20:12:52)

2 (by ExternalLinkService, 2024-03-26 20:18:43)

3 (by diego, 2024-04-05 13:31:32)

4 (by ExternalLinkService, 2024-04-05 13:37:31)

5 (by carolina, 2025-08-12 15:11:51)

6 (by ExternalLinkService, 2025-08-12 15:27:20)

7 (by ExternalLinkService, 2025-08-12 15:32:27)