Kalanchoe laetivirens Descoings (1997: 85)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/phytotaxa.524.4.2 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5684319 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/092F87C1-0647-DB0B-FF28-CFB02C44F99F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Kalanchoe laetivirens Descoings (1997: 85) |

| status |

|

2. Kalanchoe laetivirens Descoings (1997: 85) View in CoL View at ENA .

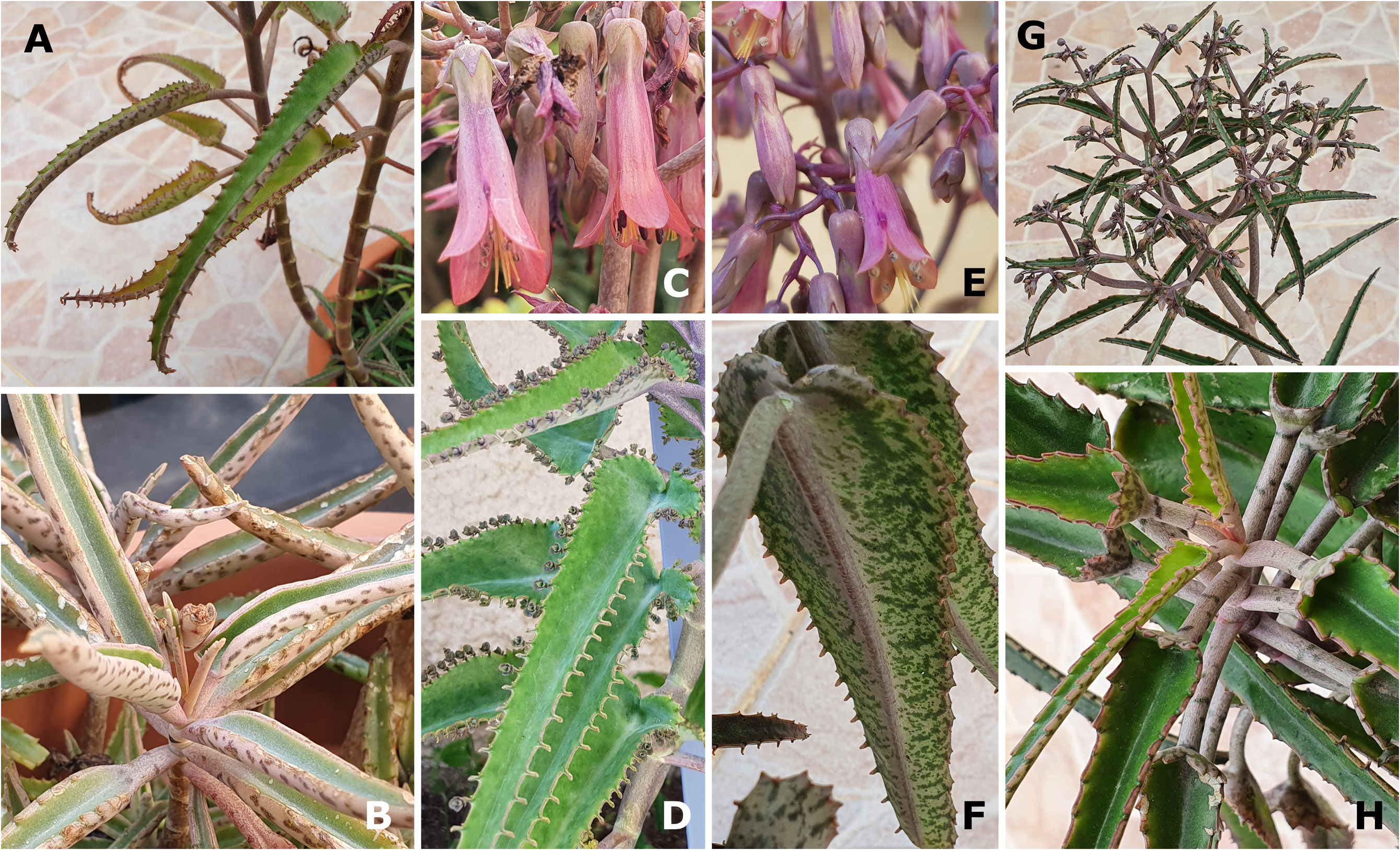

Treated as K. × laetivirens View in CoL by Smith (2020g: 105) ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ).

Homotypic synonym:— Bryophyllum laetivirens (Desc.) Byalt (2008: 463) View in CoL . Type:— MADAGASCAR. Environs de Toliara (Tulear), à quelques km au sud sur la route d’Anantsono (Saint Augustin) , bord de chemin, plante échappé du jardin de l’auberge “La Mangrove”, 25 novembre 1994, [English: “ MADAGASCAR. Surroundings of Toliara (Tulear), a few km to the south on the road to d’Anantsono (Saint Augustine) , roadside, plant escaped from the garden of the inn “La Mangrove”, 25 November 1994 ”] [B.M.] Descoings 28234 (holotype P †) . Neotype:—Ex hort. South Africa. Gauteng Province, Pretoria, 17 May 2020, G.F. Smith 1107 (PRU), designated here.

Notes on the type:—The holotype of the name K. laetivirens is a specimen, B.M. Descoings 28234, dated 25 November 1994, which Descoings (1997) stated to have deposited at Herb. P ( Descoings 1997: 85). However, this specimen is not extant at that repository (Florian Jabbour, pers. comm.). Apart from the specimen B.M Descoings 28234, no other material that would qualify as original in the sense of Turland et al. (2018: Art. 9.4) could be traced. We accordingly here neotypify (see above) the name K. laetivirens on G.F. Smith 1107, a specimen held at Herb. PRU.

The holotype of K. laetivirens was prepared from plants located a few km to the south of Toliara, Madagascar, on the road to Saint Augustine, which likely escaped from the garden of the inn “La Mangrove” ( Descoings 1997: 85). The inn “La Mangrove” probably refers to the Sarodrano Hotel, located in a mangrove forest on a small peninsula near Saint Augustine. Indeed, as of 2018, K. laetivirens is still growing along the road adjacent to the peninsula just north of Saint Augustine, and is still being cultivated at the nearby lodge (pers. obs. by one of us, JI). The neotype material designated here was possibly derived from clonal material of the garden-based Arboretum d’Antsokay, Toliara. This garden-based population of K. laetivirens was reportedly originally derived from the Isalo Massif (see “Natural distribution”, below), and later sampled by O. Olsen and introduced into cultivation around the world as ISI 95-36, HBG 70004 ( Shaw 2008: 25, and see also http://media.huntington.org/ISI/corrections.html). It is likely that the populations that escaped from the garden of the inn “La Mangrove” from which the holotype of the name K. laetivirens was prepared, were also propagated from populations cultivated in Toliara, and therefore originated from the same population that was later distributed globally.

Vegetative reproduction through the copious number of leaf marginal bulbils is the most common reproductive strategy in this species and seed fertility is low. It is likely therefore that the material preserved as both the holotype † and as the neotype originated from the same natural population in the Isalo Massif , Madagascar (see below) .

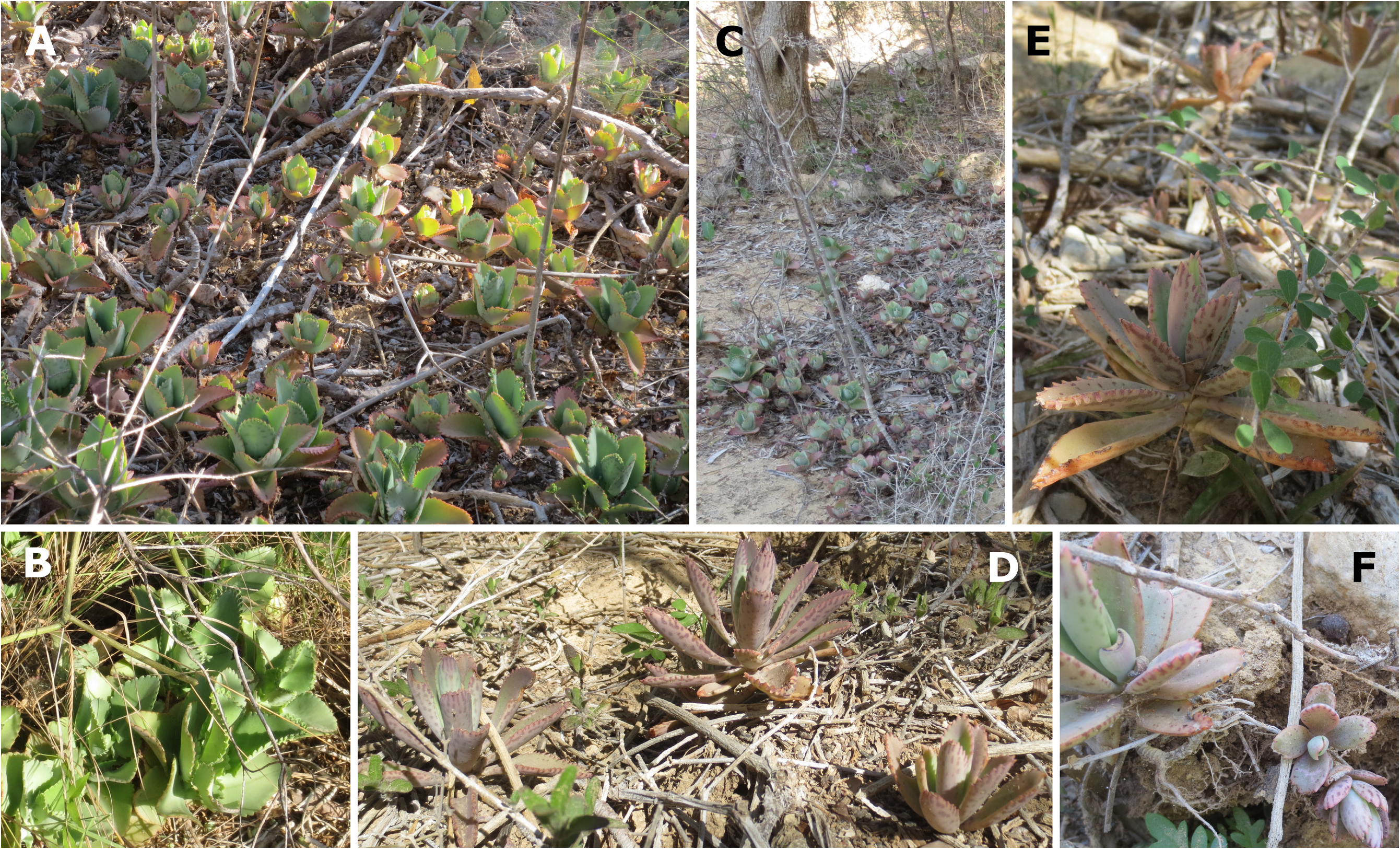

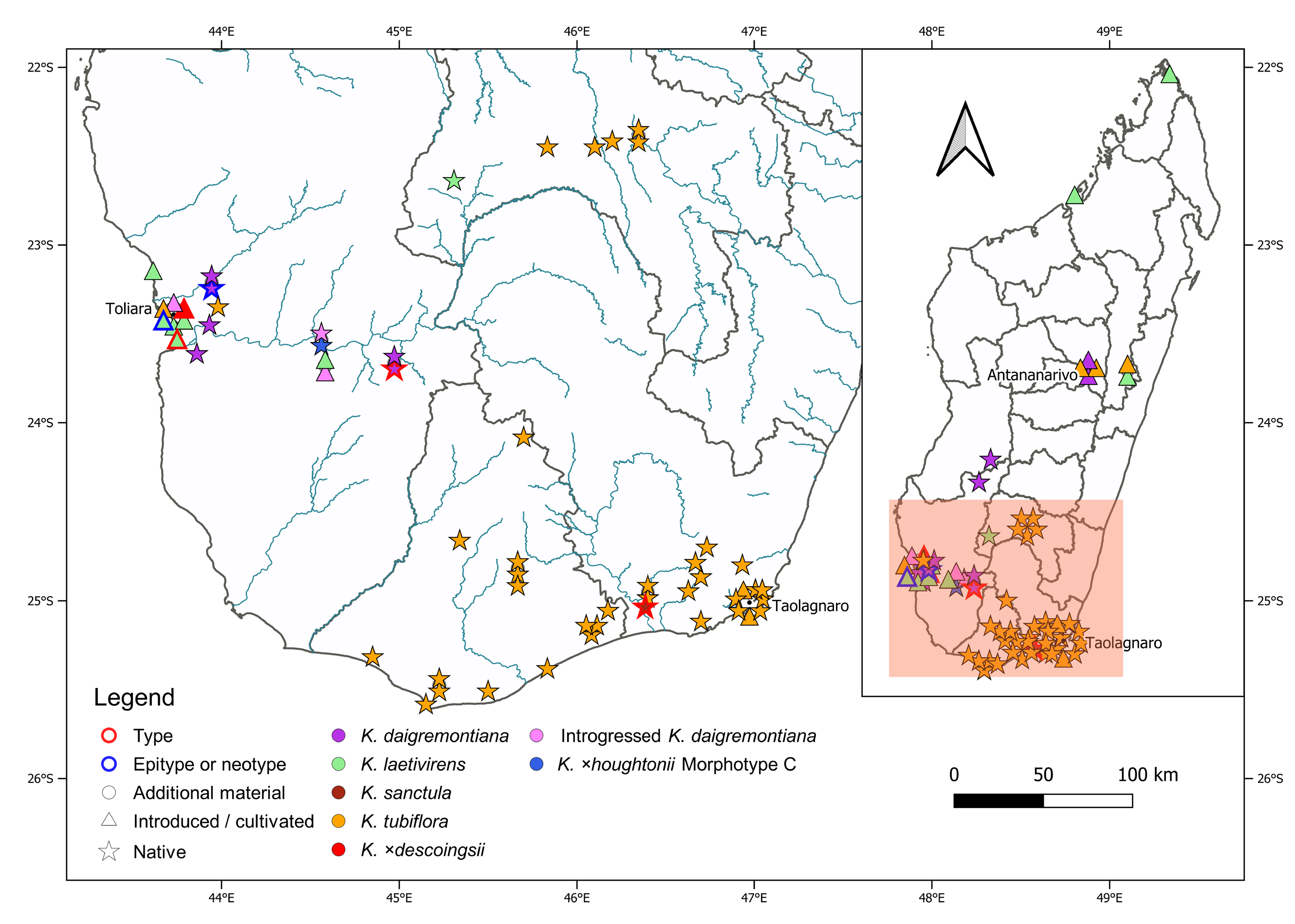

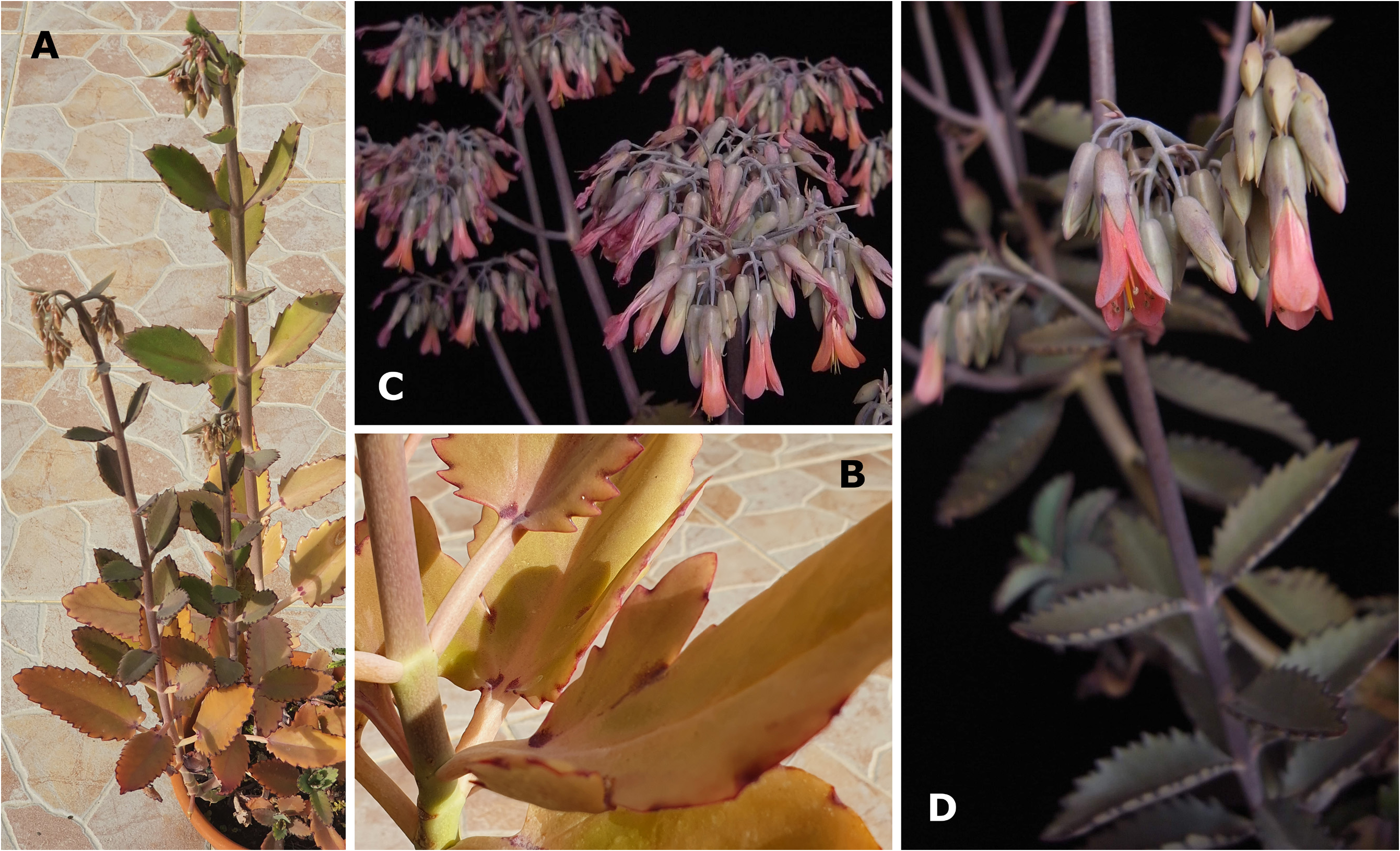

Natural distribution:—Southern Madagascar, Isalo Massif ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 ). At the time that Descoings (1997) described K. laetivirens he had not seen material of this species in the wild. Regarding the natural distribution of K. laetivirens, Descoings (1997: 85) stated the following: “ RÉPaRTITION: la localité d’origine se situe au col des Tapia, à environ 170 km au nord-est de Toliara sur la route d’Ihosy et Fianarantsoa, aux portes du massif gréseux de l’Isalo. Cette information nous a été donnée par Monsieur Hermann PETIGNAT qui cultive cette espèce à Toliara, dans son jardin botanique de l’Arboretum d’Antsokai. Les plantes vues à Saint Augustin proviennent de ce jardin. [English: “DISTRIBUTION: the place of origin is located at the Tapia Pass, about 170 km northeast of Toliara on the road to Ihosy and Fianarantsoa, at the entrance to the sandstone massif of Isalo. This information was given to us [B.M. Descoings] by Mr Hermann PETIGNAT who cultivates this species in Toliara, in his botanical garden in the Arboretum d’Antsokay. The plants seen in Saint Augustine [from where material deposited as the holotype was collected] come from this garden.”] One of us (JI) observed the species at the locality from where Mr Hermann Petignat reported it ( Fig. 7A–B View FIGURE 7 ), as well as at the Arboretum d’Antsokay ( Fig. 5A–C View FIGURE 5 ).

Numerous recent observations additionally place K. laetivirens in populous or urban areas across Madagascar, specifically, in Ifaty [https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/56394567], and Manasoa [https:// www.inaturalist.org/observations/12919994] in southwestern Madagascar, as well as in Anjajavy [https://www. inaturalist.org/observations/2633188] in northwestern Madagascar, and Antsiranana [https://www.inaturalist.org/ observations/55629658] in northeastern Madagascar. These observations suggest that K. laetivirens may now be established, possibly as escapes from cultivation across Madagascar, well beyond the range communicated to Descoings by Hermann Petignat ( Descoings 1997).

Taxonomic notes:—The proposed connection between K. laetivirens and the hybrid with the formula K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora , which was created and illustrated by Resende & Viana (1965: 180, 195 [Fig. 35], 196 [Fig. 36]) and referred to as ‘ Bryophyllum × crenodaigremontianum ’, was mentioned in Shaw (2008: 25) and later investigated by Smith (2020g: 105). As noted in Smith (2020g), material of K. laetivirens and K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora are indeed remarkably similar, especially in their broad, large, bright green leaves that, at least adaxially, are generally unmarked by any maculation or colour patterning other than towards the margins, as well as in the general size of mature leaves, the thick, herbaceous stems of the material, and the extensive inflorescences of the two entities.

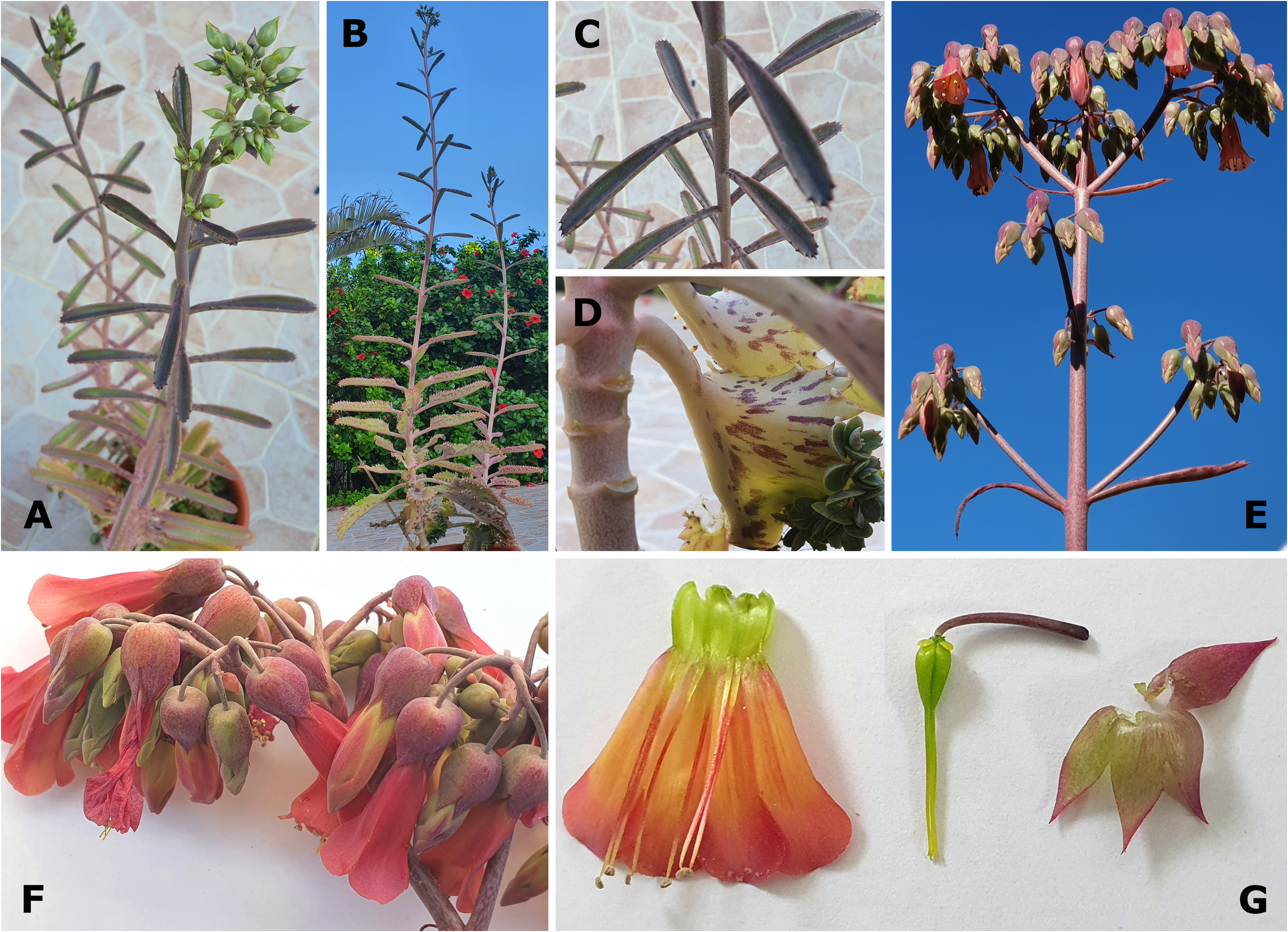

Nevertheless, several diagnostically significant differences can be observed between these plants ( Smith 2020g: 99). To allow a better comparison of K. laetivirens with the hybrid K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora created by Resende & Viana (1965), one of us (RS) recreated this combination in cultivation in Israel ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ). In addition, we were able to access a similar hybrid, K. daigremontiana × K. fedtschenkoi Raymond-Hamet & Perrier de la Bâthie (1915: 75) , for examination. The latter material was created by Sheng Jian Lu and Hung I Lu, separately, in Taiwan ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ). Significant differences observed between K. laetivirens and the two hybrids mentioned above are:

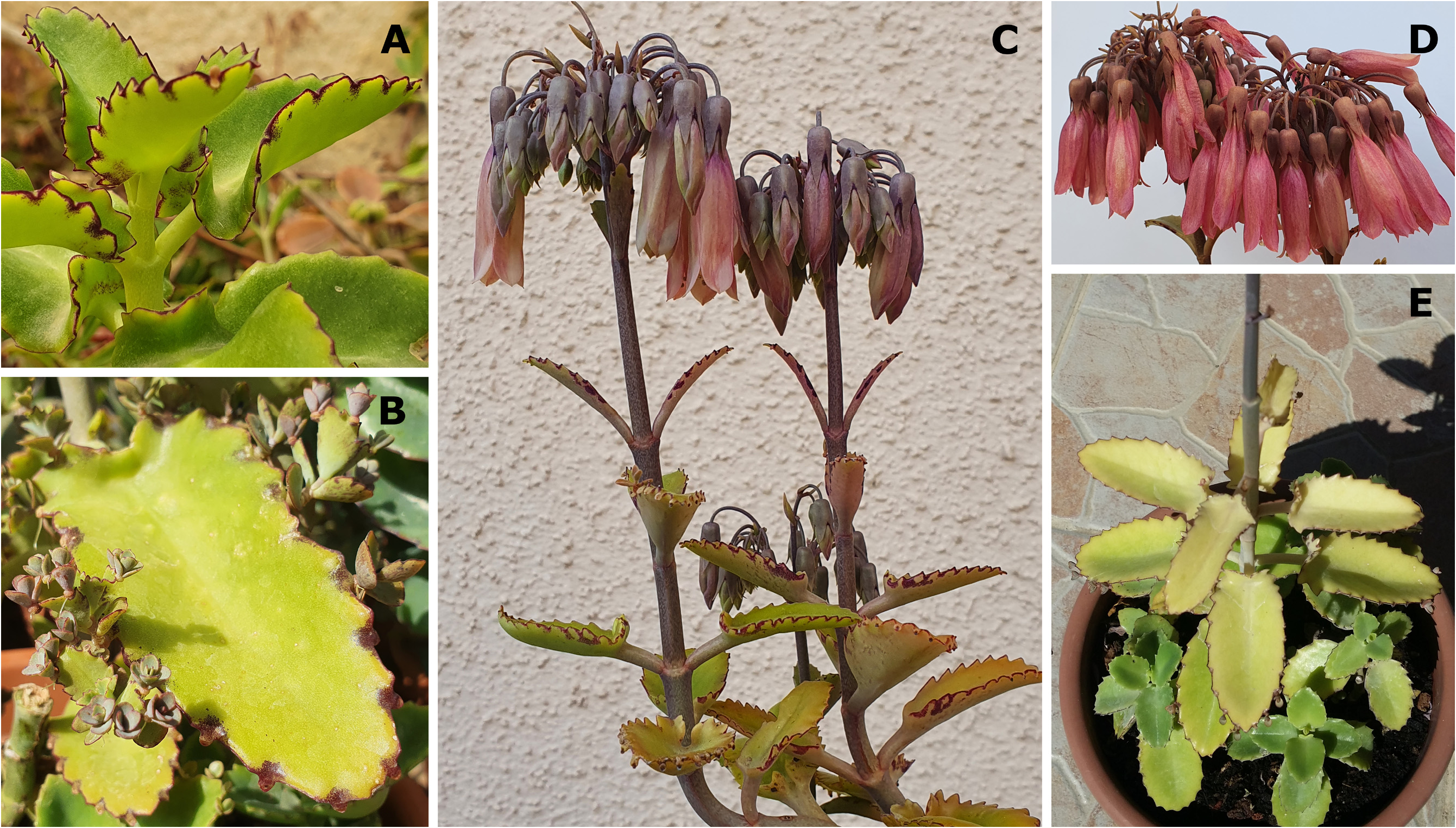

1. Resende and Viana’s hybrid ( K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora ) is not constitutively bulbiliferous, whereas K. laetivirens is (see Garcês et al. 2007). Kalanchoe laetivirens is one of the most strongly phyllo-bulbiliferous species, producing many dozens of large-sized, many-foliated bulbils on each mature leaf. Bulbil production in K. laetivirens occurs on dedicated, well-developed pedestals that are spathulate in shape and down-curved towards the abaxial leaf blade surface to facilitate the placement, especially once severed from the pedestals, of the bulbils on, or at least closer to, the ground and therefore below the substantial dentations along the leaf blade margins, which are subducted by the bulbil pedestals. However, the hybrid of Resende and Viana is at most induced or semi-constitutively bulbiliferous, and pedestals and/or bulbil formation cannot be readily observed ( Resende & Viana 1965: Figs 35 & 36). Observations of live F 1 material of K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora and K. daigremontiana × K. fedtschenkoi shows that these combinations produce induced phyllo-bulbiliferous hybrids, that form very reduced, sessile, and indistinct pedestals after bulbil formation, and never ahead of it.

2. The F 1 hybrids of K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora and K. daigremontiana × K. fedtschenkoi that we observed, as well as K. laxiflora and K. fedtschenkoi , are perennials. In contrast, both K. daigremontiana and K. laetivirens are multi-annuals that only flower once in their life cycles, following the culmination of one to three years of vegetative growth. However, it is not clear whether Resende and Viana’s hybrid was perennial or (multi-)annual.

3. Though impossible to tell from the illustrations provided by Resende and Viana, the live F 1 material we observed do not share the unique growth habit and phenological development of K. laetivirens (and of K. ×descoingsii, for that matter; see below). Kalanchoe laetivirens and hybrids derived from it are low-growing for most of their vegetative life span, forming wide, densely foliated, solitary pseudo-rosettes, with the leaves presenting especially thick, short petioles, and large, broad leaf blades. Then, during the year in which they will flower, the plants can increase in height for up to more than a factor of ×4, developing leaves bearing longer petioles and shorter, narrower leaf blades. The hybrids we observed, as well as K. laxiflora , and K. fedtschenkoi , gradually elongate in a manner more typical of Kalanchoe in general during their development, do not remain as low-growing rosettes for most of their vegetative stage, and often branch just prior to, or after, flowering.

4. Kalanchoe laetivirens is unique among representatives of K. sect. Invasores by the basal portion of the stem being extremely wide. Furthermore, the lower leaves are distinctly thick-petiolate and amplexicaul, resulting in nodal scars that give the stems a quadrangular appearance. These traits are absent in Resende and Viana’s hybrid and the hybrids we observed, as well as in K. daigremontiana , K. laxiflora , and K. fedtschenkoi .

5. In Resende and Viana’s hybrid and the ones with the same or a similar parentage that we observed, the leaves transition more gradually towards the peduncle when compared to those of K.laetivirens .Though also usually auriculate, in the hybrids the auricules are often shorter, especially in lower leaves. The basal leaves of K. laetivirens tend to also be extremely broad, more so than in the hybrid of Resende and Viana, and the hybrids we observed. Notably, K. laetivirens does not produce lobed leaves, whereas some of Resende’s F 2 hybrids are conspicuously trilobate ( Resende & Viana 1965: 196, Fig. 36). Moreover, we observed basally trilobate leaves, though only barely so, in F 1 hybrids of both K. daigremontiana × K. laxiflora and K. daigremontiana × K. fedtschenkoi , as well as in K. ×descoingsii (see below). This suggests that while the leaves of K. daigremontiana and K. laetivirens are not trilobate, their hybrids most often tend to be so, at least obscurely.

6. Kalanchoe laetivirens further differs from the hybrid of Resende and Viana and the similar hybrids we observed in some flower traits, including colour. The calyx of K. laetivirens is particularly short and small, similar to that of K. daigremontiana and K. sanctula , whereas the calyx and calyx tube of the hybrids are intermediate between those of the larger ones of K. laxiflora and K. fedtschenkoi , and is therefore longer, with the calyx tube of the hybrids being especially elongated in comparison. The succulent calyx texture of K. laetivirens further differs from the flimsier calyx texture in the hybrids. Finally, K. laetivirens , K. daigremontiana , and K. sanctula flower in shades of pink-purple, often with whitish green infusion, but lacking orange pigmentation ( Figs 7D View FIGURE 7 and 8C–D View FIGURE 8 , and as Smith 2020g: 102, 104 recorded and illustrated for K. laetivirens ), whereas the flower colour of the hybrids we observed is often salmon- to deep red ( Figs 10D View FIGURE 10 and 11C–D View FIGURE 11 ), a combination of pink-purple with the orange flower colour of K. laxiflora and K. fedtschenkoi . Note though that some forms of K. laetivirens produce flowers with substantial white sections ( Smith 2020g: Figs 5 View FIGURE 5 , 6 View FIGURE 6 , 8 View FIGURE 8 , and 9).

We conclude that K. laetivirens not only differs from the hybrid of Resende and Viana and combinations similar to it in several diagnostic traits, but also possesses some unique traits among representatives of K. sect. Invasores, for example its unique phenology, thickened lower stem and leaves, as well as its calyx morphology (discussed above). Many of the traits present in K. laetivirens are not intermediate between any two related species.

Given their multiple, specialised reproductive strategies, including the production of large numbers of bulbils on leaf margins, multi-annual representatives of K. sect. Invasores, including K. daigremontiana and K. laetivirens , do not rely exclusively on sexual reproduction to ensure the establishment of the next generation. Aspects of the reproductive biology of these species, such as the reduced viability of seed and the occurrence of a high frequency of deformed flowers ( Smith 2020g, reported for K. laetivirens ), also commonly occur in K. daigremontiana ( Garcês et al. 2007, Herrera & Nassar 2009, pers. obs. by the authors), and in K. sanctula . A decreased reliance on sexual reproduction, as opposed to vegetative reproduction, likely resulted in a reduction in the maintenance of uniform and viable fertile structures. However, the evolution of asexual reproduction in the genus, particularly in constitutively phyllo-bulbiliferous species, such as K. daigremontiana and K. laetivirens , is not yet fully understood. Regardless, as noted by Smith (2020g: 97) and Smith & Shtein (2021: 247, Fig. 3D View FIGURE 3 ) for K. daigremontiana and as shown in this paper for K. laetivirens , both K. daigremontiana and K. laetivirens do produce at least some viable seed, and ample interspecific hybrids.

The type specimen of K. laetivirens was collected as a garden escape and not in the wild ( Smith 2020g: 100). However, Descoings (1997: 85) was informed that the species originated from the Isalo Massif (see ‘Natural distribution’ of K. laetivirens , above), where one of us (JI) photographed it ( Fig. 7A–B View FIGURE 7 ). The natural distribution range of K. laetivirens is therefore not known to be sympatric with those of either K. daigremontiana (see below regarding the occurrence of K. daigremontiana at “Isalo”.) or K. laxiflora , two species offered as possible parents of K. × laetivirens ( Smith 2020g: 105) . Note though that hybridisation between species grown in a garden is a common occurrence (see ‘Introduction’ for references). While both K. daigremontiana and K. laetivirens occur naturally in southwestern Madagascar, the original habitat of K. laetivirens in the Isalo Massif, as reported to Descoings (1997: 85), is over 100 km away from the closest recorded K. daigremontiana occurrence to the south, the type locality of the latter species, the Androhiboalava Mountain, near Benenitra, as well as from the Marosavoha Mountain in the same region ( Cristini 2020), and over 150 km away from the closest recorded occurrence of K. daigremontiana to the north, in the Makay Massif ( Smith & Shtein 2021: 246, Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 )—three out of four occurrences mentioned by Raymond-Hamet & Perrier de la Bâthie (1914: 131) in the protologue of K. daigremontiana . A fourth occurrence observed by Perrier de la Bâthie, in the Isalo region, was also mentioned. However, no exsiccata or recent photographic evidence or other observations exist to corroborate this (see Supplementary file). It is possible that Perrier de la Bâthie (in Raymond-Hamet & Perrier de la Bâthie 1914) might in fact have referred to K. laetivirens , which was then still undescribed, when he documented this locality for K. daigremontiana , or that the latter species is indeed also present there ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 ). In contrast, K. laxiflora is only known to naturally occur in east-central and southeastern Madagascar, though some forms of the related species, K. fedtschenkoi , do occur in the Isalo Massif.

These morphological and geographical considerations suggest that K. laetivirens should be treated as an accepted species, closely related to K. daigremontiana and K. sanctula .

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Kalanchoe laetivirens Descoings (1997: 85)

| Shtein, Ronen, Smith, Gideon F. & Ikeda, Jun 2021 |

Bryophyllum laetivirens (Desc.)

| Byalt 2008: 463 |

laetivirens

| , Descoings 1997 |