Actinopus casuhati Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/megataxa.2.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D8203766-9E7B-468F-9E75-F21393A1BA3D |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5655715 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0975136A-FF74-CEA6-FCD5-FBF8D8AE3B54 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Actinopus casuhati Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018 |

| status |

|

Actinopus casuhati Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018 View in CoL

Actinopus casuhati Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018: 32 View in CoL View Cited Treatment , fig. 13 A–G, 14 A–D, 45 (holotype ♂, [38º 8’ S 61º 48’ W], Sierra de La Ventana, Buenos Aires, Argentina, iii.1972, Cesari leg., MACN-Ar 36609; and paratype ♀, [38º 3’ S 62º 1’ W], Parque Provincial “Ernesto Tornquist”, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 8.iv.2010, G. Pompozzi, LZI 0141; not examined); World Spider Catalog, 2020.

Diagnosis. Females of Actinopus casuhati differs from those of all other species of Actinopus , except from those of A. gerschiapelliarum Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018 , (fig. 19 C–D) and A. argenteus ( Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018, fig. 11 C), by the presence of a sub-apical constriction in the spermathecae. According to Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff (2018), they differ from those of A. argenteus , by tíbia III with additional spines apical to the crown, and from those of A. gerschiapelliarum by the larger body size and larger number of retrolateral thorns on tibiae II ( Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018, fig. 14 B).

Description. See Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff (2018: 32).

Distribution. ARGENTINA: Buenos Aires.

Actinopus indiamuerta Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018

Actinopus indiamuerta Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018: 43 View in CoL View Cited Treatment , fig. 20 A–D, 44 (holotype ♀, [26º 32’ S 65º 15’ W], Ruta 9, Río India Muerta, Tucumán, Argentina, ix.1994, P. Goloboff leg., MACN-Ar 36626); World Spider Catalog, 2020.

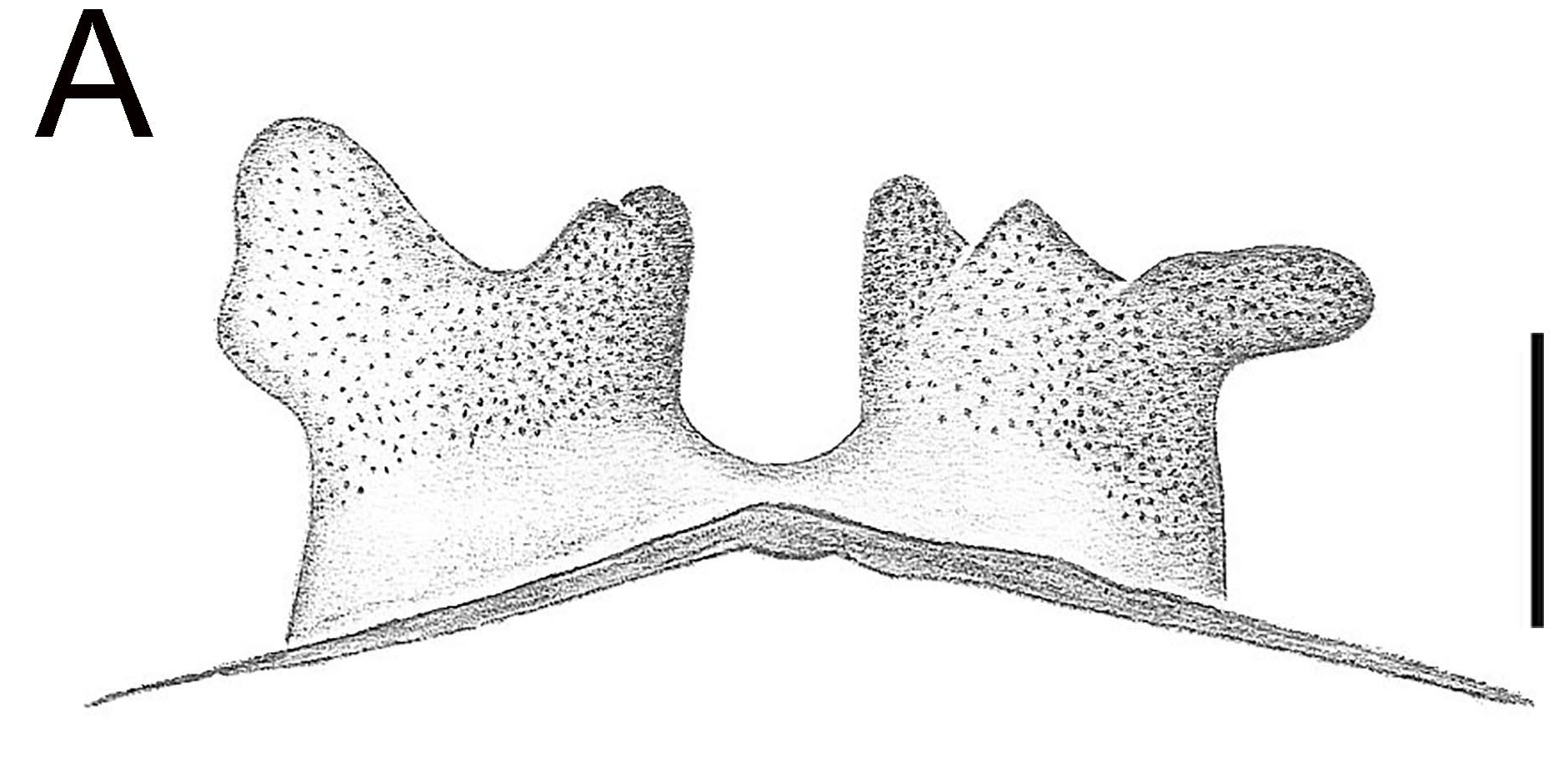

Diagnosis. According to Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff (2018), females of A. indiamuerta can be readily distinguished by the wide, semicircular labium with few cuspules (Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018, fig. 20 B) and by the short spermathecae, with perpendicular external lobe (Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018, fig. 20 D).

Description. See Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff (2018: 43).

Distribution. ARGENTINA: Tucumán.

Discussion

The present paper treats the taxonomy of 80 species of Actinopus (42 newly described, 18 redescribed, in addition to the re-evaluation of the type species, A. tarsalis , redescribed by Miglio et al. (2012), A. insignis , redescribed by Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff (2018) and other 18 recently described species from Bolivia and Argentina by Ríos (2014), Ríos-Tamayo (2016) and Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff (2018). These results are derived from the examination of nearly 1375 adult specimens, an effort that also resulted in the discovery of the unknown females of A. dubiomaculatus and A. cucutaensis , and the unknown males of A. nattereri . The criteria used to proceed with these matches included congruent morphological characters and geographical distribution. In the case of A. dubiomaculatus , in addition to these criteria, males and females were collected in the same sampling event. Despite the large number of examined specimens, the vast majority of species here recognized as valid remain known only from one sex, a situation that makes the taxonomic knowledge of Actinopus still unsatisfactory. Most sp. nov. here presented are known only from males; no sp. nov. based solely in females are presented here because we believe that describing sp. nov. based only in females is not advisable due to the lack of straightforward diagnostic characters.

From the 49 currently nominal species valid for Actinopus , 10 were here declared as species inquirendae on grounds that the type specimens were based on juvenile specimens or, even if based on adult specimens, they are lost. However, a great effort was made here to avoid making unnecessary names available. Thus, the identity of some species with missing types was established by the careful study of original descriptions. Despite the enormous difficulty of identifying species based on old descriptions, which are generally poorly informative and devoid of illustrations, congruence of morphological characters and geographic distributions of the material examined with the information in the literature rendered the harnessing of five old historic names, A. pusillus , A. dubiomaculatus , A.echinus , A.nattereri and A.paranensis , which otherwise should be declared as unrecognizable.

The taxonomy of Actinopus is particularly difficult not only for the unavailability of types or for the uninformative literature, but also due to the absence of unique morphological details that could provide effective diagnosis to recognize species and groups of species. Thus, most of the taxa here recognized can be identified only by combinations of characters. Perhaps this is one of the main reasons for the fact that the diversity of the genus has been so underestimated in the past 200 years, with few and isolated new descriptions. Even discounting the unrecognizable species, the present paper increases the known species richness of Actinopus in nearly 60,5%, revealing a possible scenario of very high species endemism in the genus.

To optimize identifications in this revision, 11 species groups are diagnosed and keyed. These groups are only taxonomic tools, not supposed to primarily represent putative monophyletic groups, and were based mainly in characters from the male palp. From the 80 species here diagnosed, 12 could not be included in these groups because they are known only from females or due to their divergent male palpal morphology. The species known only from females are A.echinus , A.princeps , A.trinotatus , A. wallacei A. xenus A. casuhati and A. indiamuerta . The male of one of these species, A. wallacei , was described by Schiapelli & Gerschman, 1945, but since their material was not available the identity of the male form of this species can not be determined here and, consequently, this species was not included in any group. The species known by males that were not placed in groups of species are A. jamari , A. clavero , A. apiacas and A. panguana . The male palpal morphology presented by these species is considerably different from that presented for other Actinopus and each one of these species would stand in a group of their own.

Most characters proposed here to differentiate the species and groups of species are related to the male copulatory bulb, the female spermathecae and patterns of coloration (in ethanol) in legs and palps of both sexes. These color patterns are very widespread across taxa and are generated by contrasting color between articles of legs or/and palp, some of which may be paler than other articles on the same leg. The most common state of this character is the palpal tibia yellowish or orange, paler than other palpal articles. This condition is shared by all groups recognized here, except the group tarsalis . Notwithstanding that, seven additional patterns of leg coloration have been be found in Actinopus : (1) patellae, tibiae, metatarsi and tarsi of legs paler than femora (as in females of A. rufipes ); (2) tibiae, metatarsi and tarsi of legs paler than femora and patellae (as in males of A. crassipes ); (3) Metatarsi and tarsi of legs paler than other leg articles (as in males of A. dubiomaculatus ); (4) Tibia of palp, and tibiae, metatarsi and tarsi of legs paler than other articles (as in A. pusillus ); (5) Tibia of palp, and metatarsi and tarsi of legs paler than other articles (as in A. dioi ); (6) Patella and tibia of palp paler than femur and tarsus (as in males of A. rufipes ); and (7) Tibia and tarsus of palp paler than other articles (as in A. azaghal ).

Other important somatic (non-genitalic) characters, at least to define the groups osbournei and goloboffi , are related to the sternal morphology, particularly the patterns of distribution of sternal sigilla: (1) converging to the middle of the sternum but separated (as in most species, eg. A. jaboticatubas , Fig. 39 C View FIGURE 39 ); or (2) fused medially of sternum (as in group osbournei , Figs 133 C View FIGURE 133 , 136 C View FIGURE 136 ). The group goloboffi is characterized by a unique depression in the middle of the sternum.

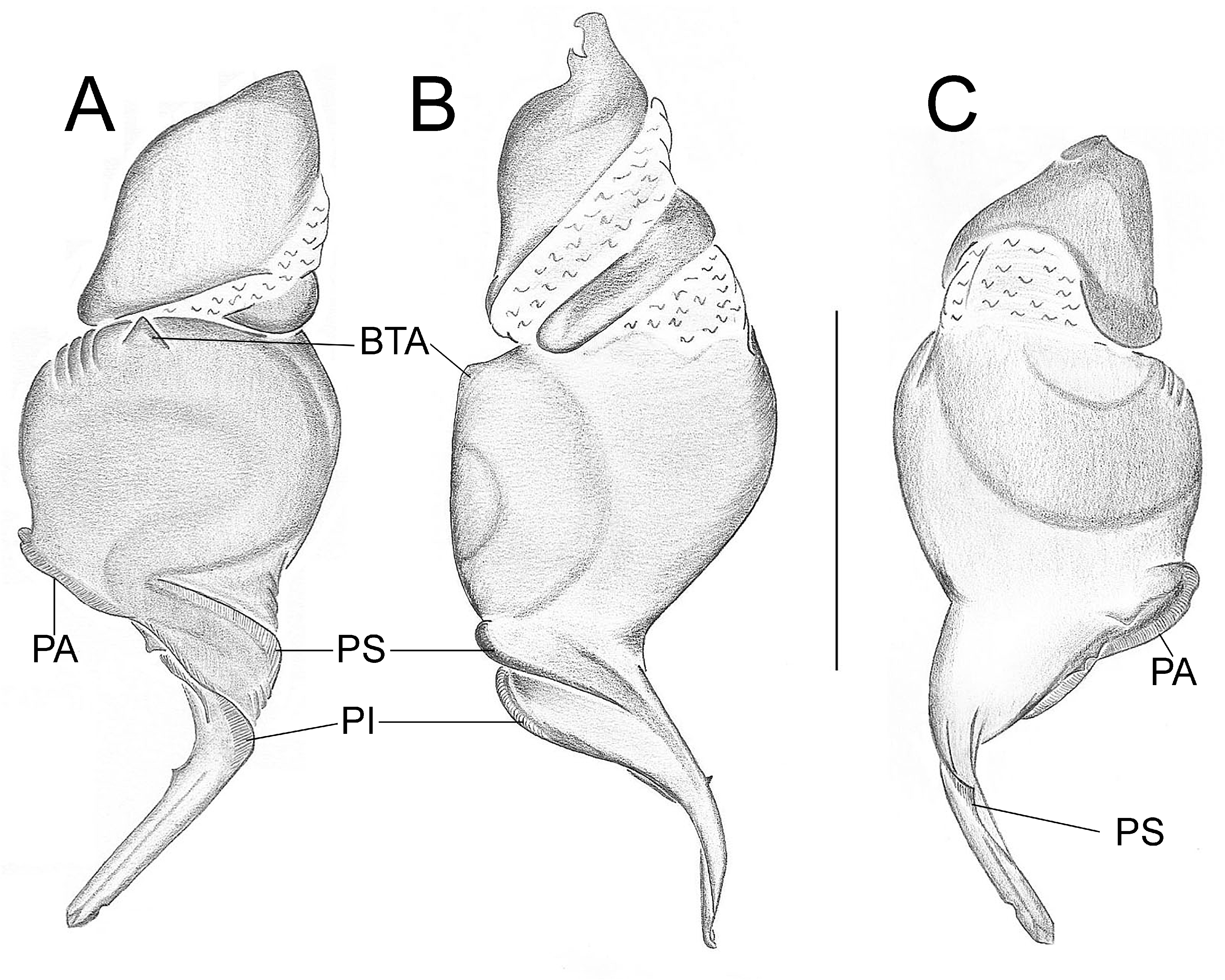

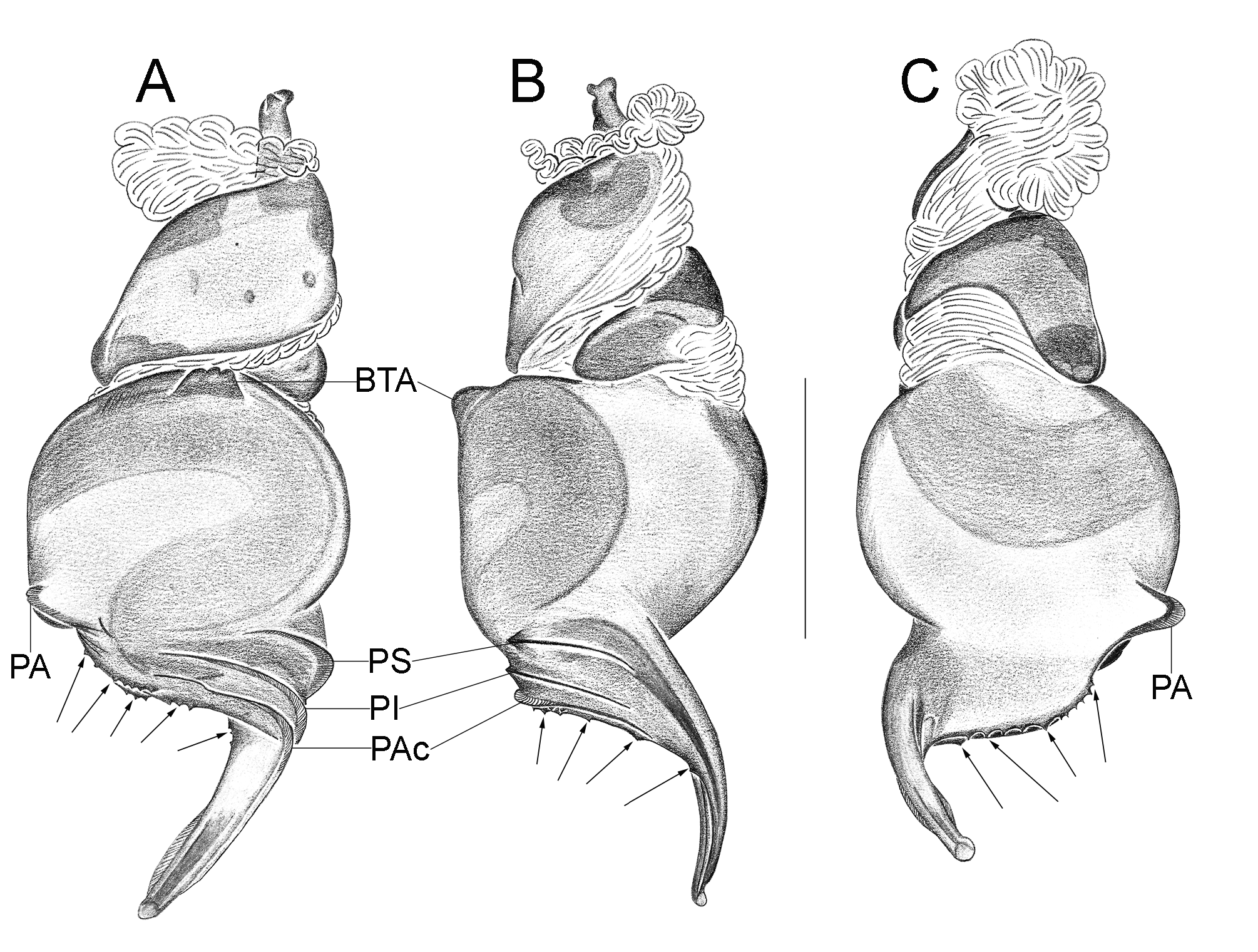

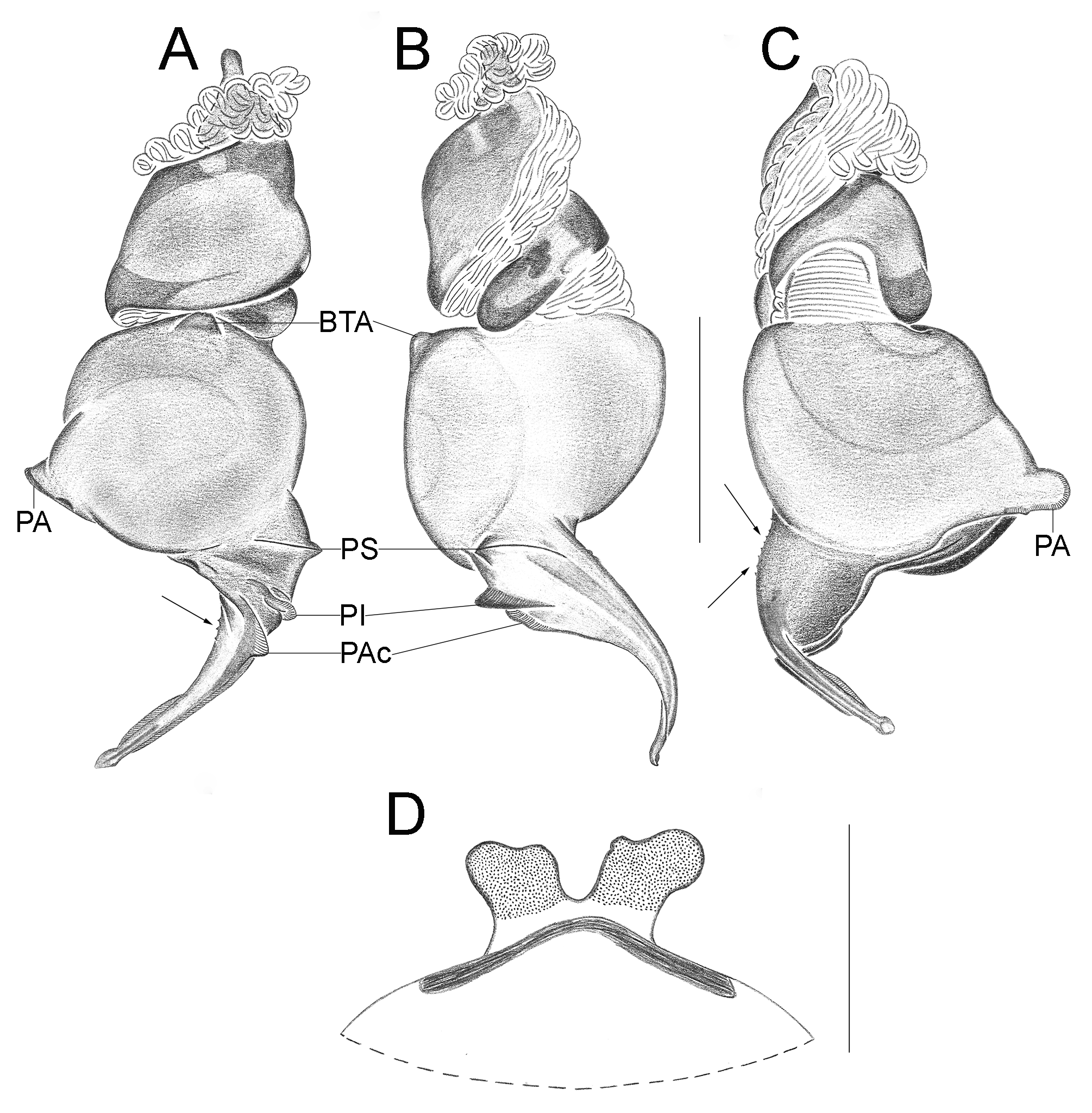

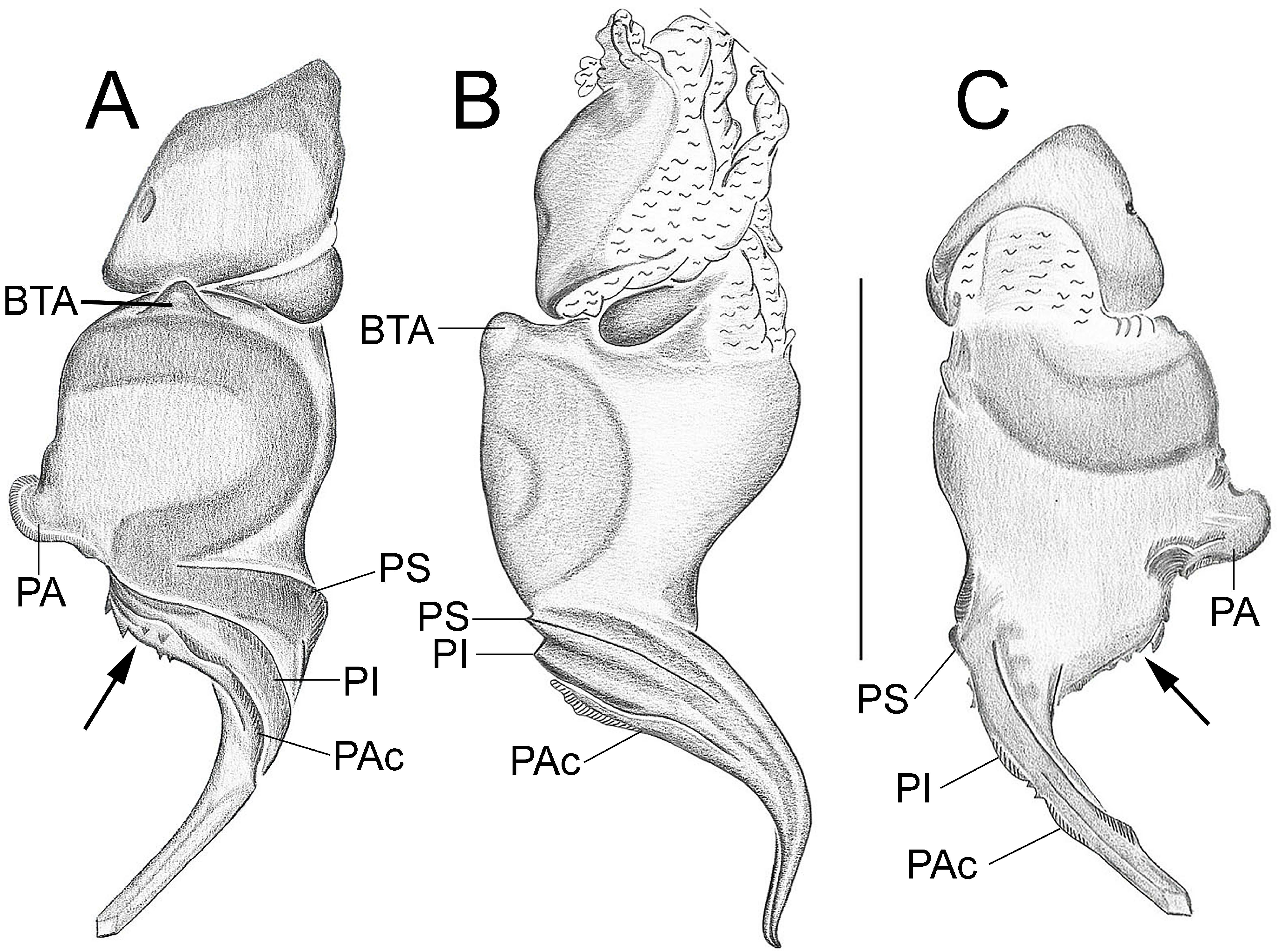

Important diagnostics characters related to the copulatory bulb of males are based on the absence or in the shape of apophyses, keels and tegular processes. These structures are always associated with the tegular surface or the embolus and were described as follows: (1) Basal tegular apophysis (BTA) present (in most species, Fig. 38 A View FIGURE 38 ) or absent (as in group tarsalis and A. concinnus , Figs 9 A View FIGURE 9 , 195 A View FIGURE 195 , respectively); (2) Position of BTA in prolateral view of copulatory bulb: Displaced ventrally in relation to a middle longitudinal line along prolateral tegular surface (as in A. laventana , Fig. 129 A View FIGURE 129 ); Placed medially on prolateral tegular surface (as in A. crassipes , Fig. 107 A View FIGURE 107 ); Displaced dorsally in relation to a middle longitudinal line along prolateral tegular surface (as in A. fractus , Fig. 21 A View FIGURE 21 ); (3) Absence (as in A. cucutaensis , Fig. 176 A View FIGURE 176 ) or presence of one (as in A. anselmoi , Fig. 171 A View FIGURE 171 ), two (as in A. fractus , Fig. 21 A View FIGURE 21 ) or three (as in most species, Fig. 107 A View FIGURE 107 ) keels visible in prolateral view of copulatory bulb; (4) Paraembolic apophysis (PA) conspicuous or inconspicuous, respectively as in A. nattereri ( Fig. 67 View FIGURE 67 A–C) and A. harveyi ( Fig. 78 View FIGURE 78 A–C); (5) PA contiguous to prolateral superior keel (as in A. nattereri , Fig. 67 A View FIGURE 67 ), between prolateral superior and prolateral inferior keels (as in A. buritiensis , Fig. 29 A View FIGURE 29 ), contiguous to prolateral inferior keel (as in A. utinga , Fig. 103 A View FIGURE 103 ), between prolateral inferior and prolateral accessory keels (as in A. cornelli , Fig. 62 A View FIGURE 62 ), or contiguous to prolateral accessory keel (as in A. rufipes , Fig. 72 A View FIGURE 72 ); (6) PA placed ventrally in relation to a middle longitudinal line along prolateral tegular surface and on prolateral tegular border (as in A. osbournei , Fig. 135A View FIGURE 135 ); or PA displaced dorsally in relation to a middle longitudinal line along prolateral tegular surface and secluded from prolateral tegular border (as in A. apiacas , Fig. 201 A View FIGURE 201 ); (7) Presence (as in A. guajara , Fig. 192 A View FIGURE 192 ) or absence (as in A. dioi , Fig. 138 A View FIGURE 138 ) of apical tegular process (ATP) (The tegular modification in A. jamari is here recognized as PA, not as ATP, because it’s surface present keels. Considering there is not a strong evidence of homology between these features we prefered to maintain A. jamari out from the groups.); (8) Position of ATP in prolateral view: Relatively parallel to embolus (as in A. cucutaensis , Fig. 176 B View FIGURE 176 ); or oblique in relation to the embolus (as in A. robustus , Fig. 181 B View FIGURE 181 ); (9) Position of ATP on dorsal view: Almost in the same plane in relation to embolus (as in A. cucutaensis , Fig. 176 A View FIGURE 176 ); or inserted obliquely in relation to the embolus (as in A. concinnus , Fig. 195 A View FIGURE 195 ); (10) Presence (in A. panguana , Fig. 206 View FIGURE 206 A–C) or absence (as in all other species; eg. A. obidos , Fig. 26 A View FIGURE 26 ) of dorsal tegular process (DTP).

Another informative character in the copulatory bulb is the embolar serrated area or its absence. This character may be have the following states: (1) absent (as in A. nattereri , Fig. 67 View FIGURE 67 A–C); (2) Represented by at most two cusps below the most inferior keel (PI or PAc) (as in group apalai , Figs 15 View FIGURE 15 A–C, 16 A–C); (3) Represented by three or more cusps (as in A. osbournei , Fig. 135 A, C View FIGURE 135 ). The serrated area could be also described by the position and shape of cusps. As for the position, the serrated area could be restricted to the basal portion of embolus (as in A. crassipes , Fig. 107 A, C View FIGURE 107 ); Along embolar length, below the most inferior keel (PI or PAc) (as in A. dubiomaculatus , Fig.112A, C View FIGURE 112 ); Or widespread along entire embolar surface (as in A. bocaina , Fig. 124 View FIGURE 124 A–C). The morphology of the cusps is also informative in A. bocaina , where they are square ( Fig. 124 View FIGURE 124 A–C), opposing to the sharply pointed condition, as in all other species (eg. A. pusillus , Fig. 118 View FIGURE 118 A–C).

The female spermathecae can have one (as in A. obidos , Fig. 26 D View FIGURE 26 ) or two receptacles (as in A. nattereri , Fig. 67 D View FIGURE 67 ). Each receptacle can have one (unilobed, as in A. nattereri , Fig. 67 A View FIGURE 67 ), two (bilobed, as in A. ipioca , Fig. 88 D View FIGURE 88 ) or three (trilobed, as in the right receptacle on dorsal surface of A. trinotatus , Fig. 220 A View FIGURE 220 ) lobes. The occurrence, in several species, of intraspecific variation in the shape of spermathecae and number of lobes is a complication factor and, for this reason, these characters must be evaluated in combination with another important characteristic of the female spermathecae: the distribution of pores along receptacles surface. The pore distribution may be presented as: (1) Widespread on 75% of receptacle apical portion (as in A. nattereri , Fig. 67 D View FIGURE 67 ); Occurring in 100% of the receptacle surface (as in A. laventana , Fig. 129 D View FIGURE 129 ); and (3) occurring in 100% of receptacle surface and extended to portions of the basal membrane (as in A. obidos , Fig. 26 D View FIGURE 26 ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Actinopus casuhati Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018

| Miglio, Laura Tavares, Pérez-Miles, Fernando & Bonaldo, Alexandre B. 2020 |

Actinopus indiamuerta Ríos-Tamayo & Goloboff, 2018: 43

| Rios-Tamayo, D. & Goloboff, P. A. 2018: 43 |