Yujiangolepis liujingensis, WANG ET AL., 1998

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00519.x |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10545918 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0A5287D1-973D-FFF4-66B2-FE52FC10885D |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Yujiangolepis liujingensis |

| status |

|

SPECIES YUJIANGOLEPIS LIUJINGENSIS WANG ET AL., 1998

Holotype IVPP V 1957

Wang et al., 1998: fig. 2; pl I, fig. 1

Young & Goujet, 2003, fig. 16C

DESCRIPTION

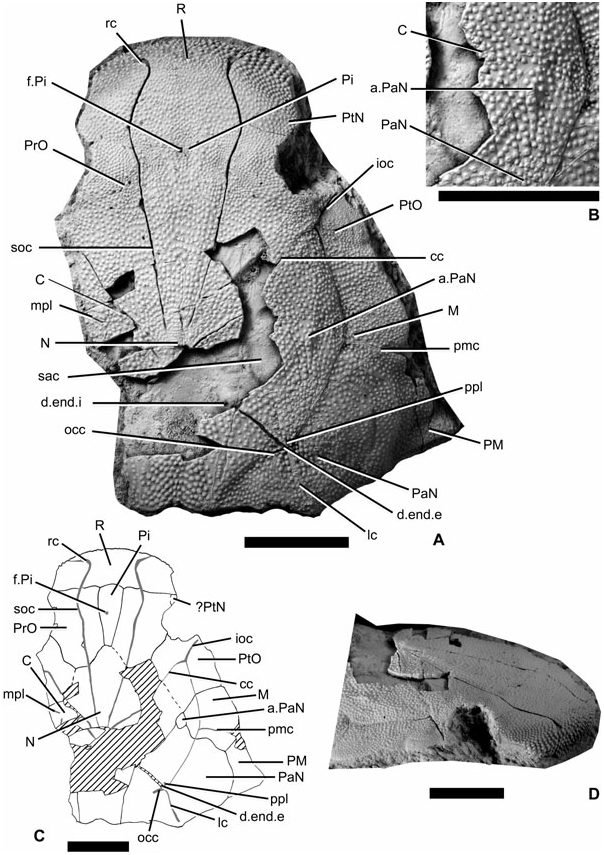

The only material available for Yujiangolepis liujingensis is a 3D-preserved subcomplete head showing a small part of the underlying neurocranium ( Fig. 2A View Figure 2 ). Neither diagenesis nor compaction seems to have altered the specimen. Radiation centres are easily recognizable because of the numerous minute tubercles around; the plate boundaries are indicated with low and very thin ridges. The ethmoid components (R, Pi, PtN, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ) are fused to the rest of the skull roof, although the boundaries of the postnasal plates are not distinguishable. From what can be seen, only a small mesial part of the postnasal plate can be detected just anterior to the right orbit. The anterior face of the rostral plate bears large and pointed tubercles, reminiscent of the snout of Wuttagoonaspis fletcheri Ritchie, 1973 (pl. 5, figs 1–3; Fig. 2D View Figure 2 ), although the rest of the ornamentation is completely different from the latter genus ( Wuttagoonaspis also exposes ridges). The rostral sensory groove (rc, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ) shows a mesial loop, as is visible in W. fletcheri (see Ritchie, 1973: text. fig. 5A), and to a lesser extent in Toombalepis tuberculata ( Young & Goujet, 2003: fig. 16). Owing to its anteromesial position, the groove is referred to the rostral groove rather than the ‘supramaxillary groove’ in W. fletcheri . A shallow depression extends posterolaterally from the loop, as in T. tuberculata . Antarctaspis mcmurdoensis does not show any loop, but this absence might be explained because of the incompleteness of the most anterior part of the snout (see White, 1968: pl. II figs 1–2). In Yujiangolepis , the rostral groove then extends ventrally. The pineal plate is elongate and very narrow. A small crack is situated at the level of the pineal foramen/eminence; hence it is impossible to say if this was a closed (eminence) or an open (foramen) structure.

The preorbital plate (PrO, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ) is a large element entirely separated from its antimere by the pineal plate. It constitutes the mesial part of the orbital margin. It is crossed longitudinally by the supraorbital groove (soc, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ), which is the posterior extension of the rostral groove.

The postorbital plate constitutes the posterior edge of the orbit. Its radiation centre classically corresponds to the junction between the infraorbital and central sensory grooves (ioc, cc, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ). The boundary with the central plate is unclear.

The case of the central plates is more problematic, because the area where they should be visible, assuming a ‘classic’ arthrodire pattern, is not preserved. We can only assess the presence of these plates owing to a slight difference in the tubercle distribution: very tiny tubercles are visible at the level of the crack (right half of the specimen; C, Fig. 2A–C View Figure 2 ) just posteriorly to the central sensory groove (cc, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ), and most probably indicate the position of the radiation centre of the plate. Unfortunately, it is impossible to determine either the mesial extension of the central plates or their size.

The nuchal plate (N, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ), although unknown in its middle part, extends further anteriorly, and contacts the preorbital and most probably postorbital plates. The supraorbital and central sensory grooves clearly converge toward the radiation centre of the nuchal plate; there is no evidence that the posterior pit-lines also converge onto this point (as the corresponding parts of the skull roof are not preserved, and as only the dorsal side of the neurocranium is exposed). The boundary between the paranuchal and nuchal plates is outlined by a low and thin ridge (see Fig. 2A View Figure 2 ).

The marginal plate (M, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ) is present mesially to the infraorbital and main lateral sensory grooves; in other words, it separates the postorbital and the paranuchal plates. Its radiation centre is located at the level of the junction between the infraorbital, main lateral, and postmarginal sensory grooves. The postmarginal plate (PM, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ) constitutes a pointed posterolateral edge of the skull roof, slightly more anterior than in other species of ‘Actinolepidoidei’ (in which it is almost at the level of the posterior margin of the paranuchal plates).

The paranuchal ensemble is very interesting in its composition of two plates. The biggest and main paranuchal plate (PaN, Fig. 2A–C View Figure 2 ) bears the main lateral sensory line groove, the occipital cross commissure, the posterior pit line, and the external foramen for the endolymphatic duct. It would be homologous with the posterior paranuchal plate of the Petalichthyida Jaekel, 1911 and of the Acanthothoraci Stensiö, 1944 . Anteriorly to this plate, the smaller one is considered here as a possible vestigial anterior paranuchal plate similar to that of the Petalichthyida and of the Acanthothoraci (a.PaN, Fig. 2A–C View Figure 2 ), because it is visible at the junction with the central and the marginal plates (‘topographic’ hypothesis for homology; see discussion below). This anterior paranuchal plate is outlined by low and smooth ridges. Contrary to what can be observed in the Petalichthyida (a group of Placodermi that is closely related to the Arthrodira and possessing two pairs of posterior pit-lines and of paranuchal plates), the anterior paranuchal plate of Yujiangolepis is not crossed by any sensory groove and is much smaller, suggesting it as a vestigial element.

Obviously, the dermal craniothoracic joint is of the ‘sliding’ type, as in all ‘Actinolepidoidei’.

The visible part of the dorsal side of the neurocranium exposes the saccula of the inner ear (sac, Fig. 2A View Figure 2 ), and the internal foramen for the endolymphatic duct on a bump (d.end.i, Fig. 2A View Figure 2 ) of the neurocranium, mesially to the nuchal–paranuchal plate boundary. The respective positions of the external (d.end.e, Fig. 2A, C View Figure 2 ) and internal foramina for the endolymphatic duct imply the possession of a long and oblique endolymphatic tube within the dermal bone that is characteristic of the Arthrodira ( Goujet, 1984) .

| IVPP |

Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.