Leptalpheus forceps Williams, 1965

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4766.1.3 |

|

publication LSID |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7670778E-F123-4ACF-A349-A04B426FD876 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3803795 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/124D87CD-FFB0-FFE1-C6EA-E029D0E8B277 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Leptalpheus forceps Williams, 1965 |

| status |

|

Leptalpheus forceps Williams, 1965 View in CoL

Figures 2–6 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6

Leptalpheus forceps View in CoL — Williams 1965: 192–197, figs. 1, 2; Williams 1984: 101, fig. 69; Anker et al. 2006b: 685 View Cited Treatment , 686, 687; Pachelle et al. 2016: 13 View Cited Treatment , fig. 6C.

Leptalpheus cf. forceps View in CoL — Anker 2008: 788 View Cited Treatment , 789, 790, 791, figs. 4, 5, 6A, B; Anker 2011: 6 View Cited Treatment , 7, figs. 3A, B.

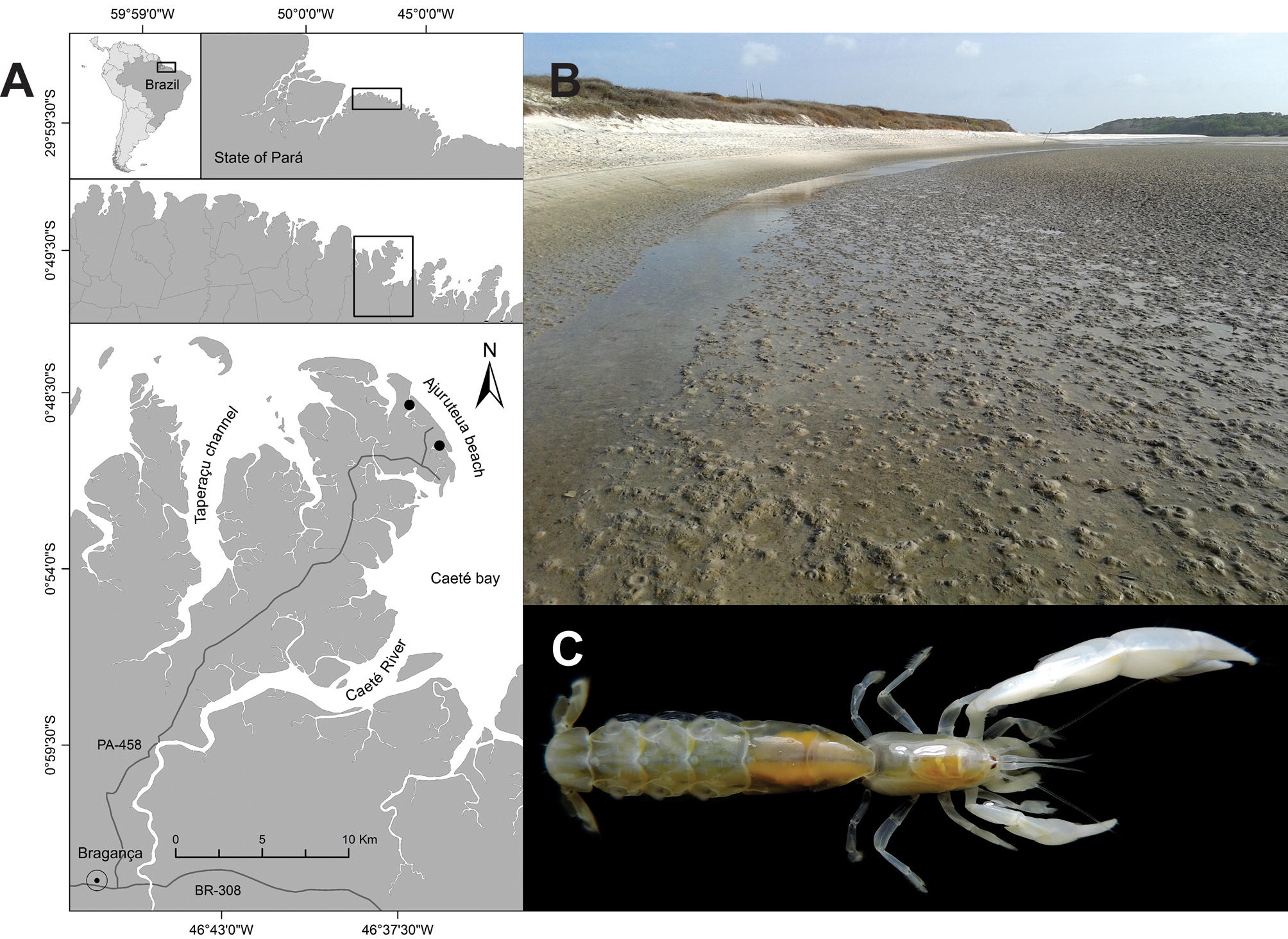

Leptalpheus aff. forceps View in CoL — Almeida et al. 2012: 15, 17, figs. 5A–D. Material examined. 20 males (CL=4.25 ± 0.61 mm; TL=11.42 ± 1.5 mm), 20 non-ovigerous females (CL=3.53 ± 0.73 mm; TL=9.72 ± 1.82 mm), and 20 ovigerous females (CL=4.27 ± 0.15 mm; TL=11.91 ± 0.38 mm); muddysandy intertidal zone of the Ajuruteua Peninsula ( Fig. 1A, B View FIGURE 1 ) in the Bragança region of the state of Pará, northern Brazil ( 046°37’8.13”W, 0°48’52.92”S; 046°36’11.81”W, 0°50’9.10”S; 046°36’9.80”W, 0°50’11.22”S); 23 June 2013, 03 March 2014, 11 April 2015, 19 March 2017, 20 May 2017, and 13 April 2018.

Description. See Williams (1965, 1984) and Anker (2008).

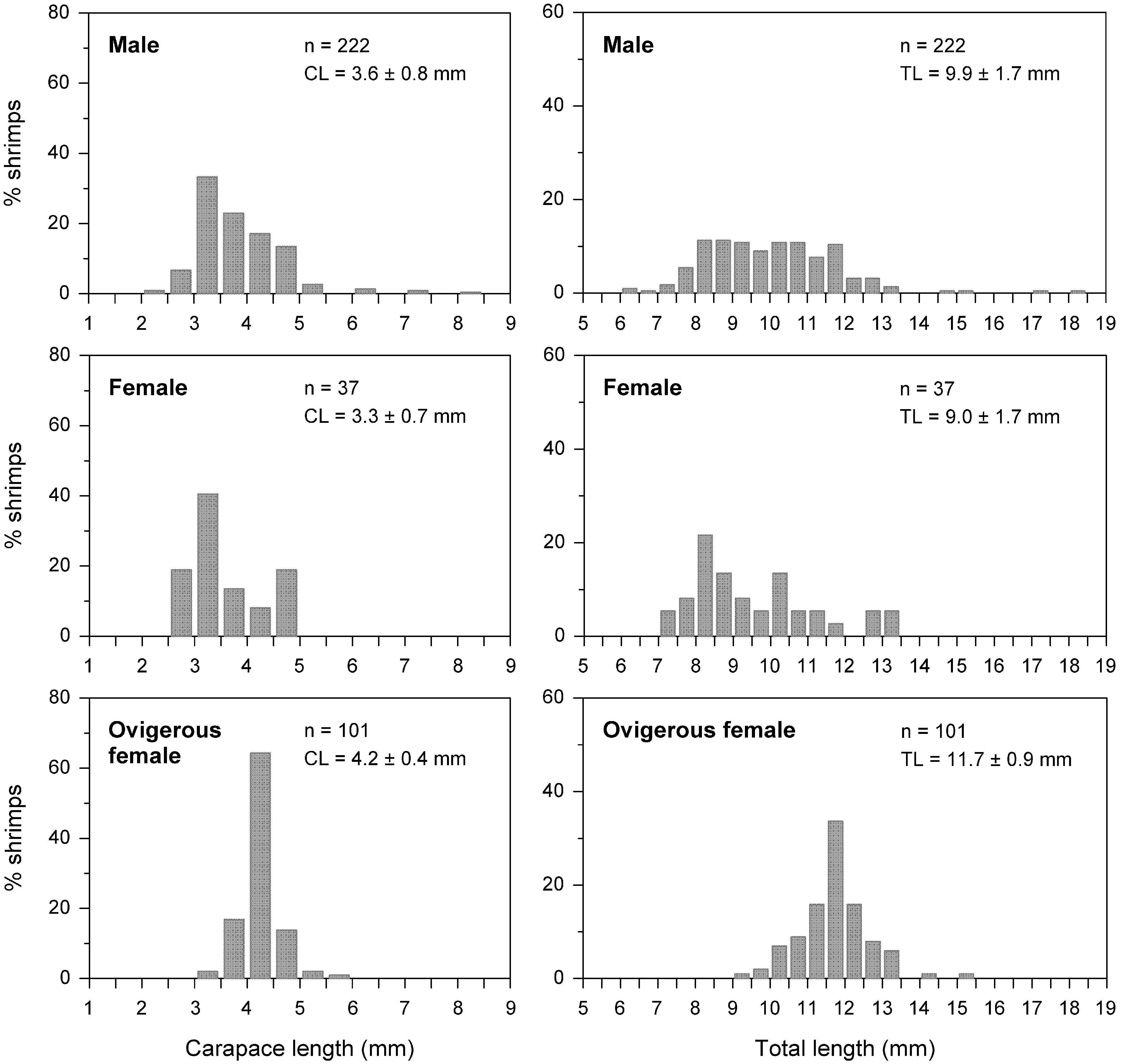

Density and population structure. A total of 360 specimens of L. forceps were obtained from the 3000 burrows of the callichirid “ghost” shrimp, Lepidophthalmus siriboia , sampled during the present study. Overall, 222 of the 360 L. forceps specimens were identified as males (61.7%) and 138 as females (38.3%), resulting in a sex ratio of 1.6M: 1F. In the case of the females, 101 individuals (73.2% of the total) had eggs in their abdomens. Shrimp density varied from 0 to 3 individuals per callichirid burrow.

In the general, male shrimps of L. forceps exhibited carapace lengths (CL) ranging from 2.4 to 8.4 mm (3.6 ± 0.8 mm), with the highest percentages of individuals (33.3 and 22.9%) being assigned to the size classes between 3.0 and 4.0 mm CL ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). The CLs of the non-ovigerous females ranged from 2.6 to 4.9 mm (3.3 ± 0.7 mm), and the highest percentage of females (40.5%) was recorded in the 3.0– 3.5 mm size class ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). The CLs of the ovigerous females ranged from 3.4 to 5.8 mm (4.2 ± 0.4 mm), with most specimens (64.3%) being recorded in the 4.0– 4.5 mm size class ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ).

The total body lengths (TL) of the male shrimps ranged from 6.3 to 18.4 mm (9.9 ± 1.7 mm), with the highest percentages of specimens (10.8–11.2%) being grouped in the size classes between 8.0 and 12.0 mm TL ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). The TLs of the non-ovigerous females varied from 7.2 to 13.3 mm (9.0 ± 1.7 mm), with most specimens being recorded in the 8.0– 8.5 mm (21.6%), 8.5–9.0 mm (13.5%), and 10.0– 10.5 mm (13.5%) size classes ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). The TLs of the ovigerous females ranged from 9.4 to 15.4 mm (11.7 ± 0.9 mm), and the highest percentages of specimens (15.8 and 33.6%) were recorded in the size classes between 11.0 and 12.5 mm TL ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ).

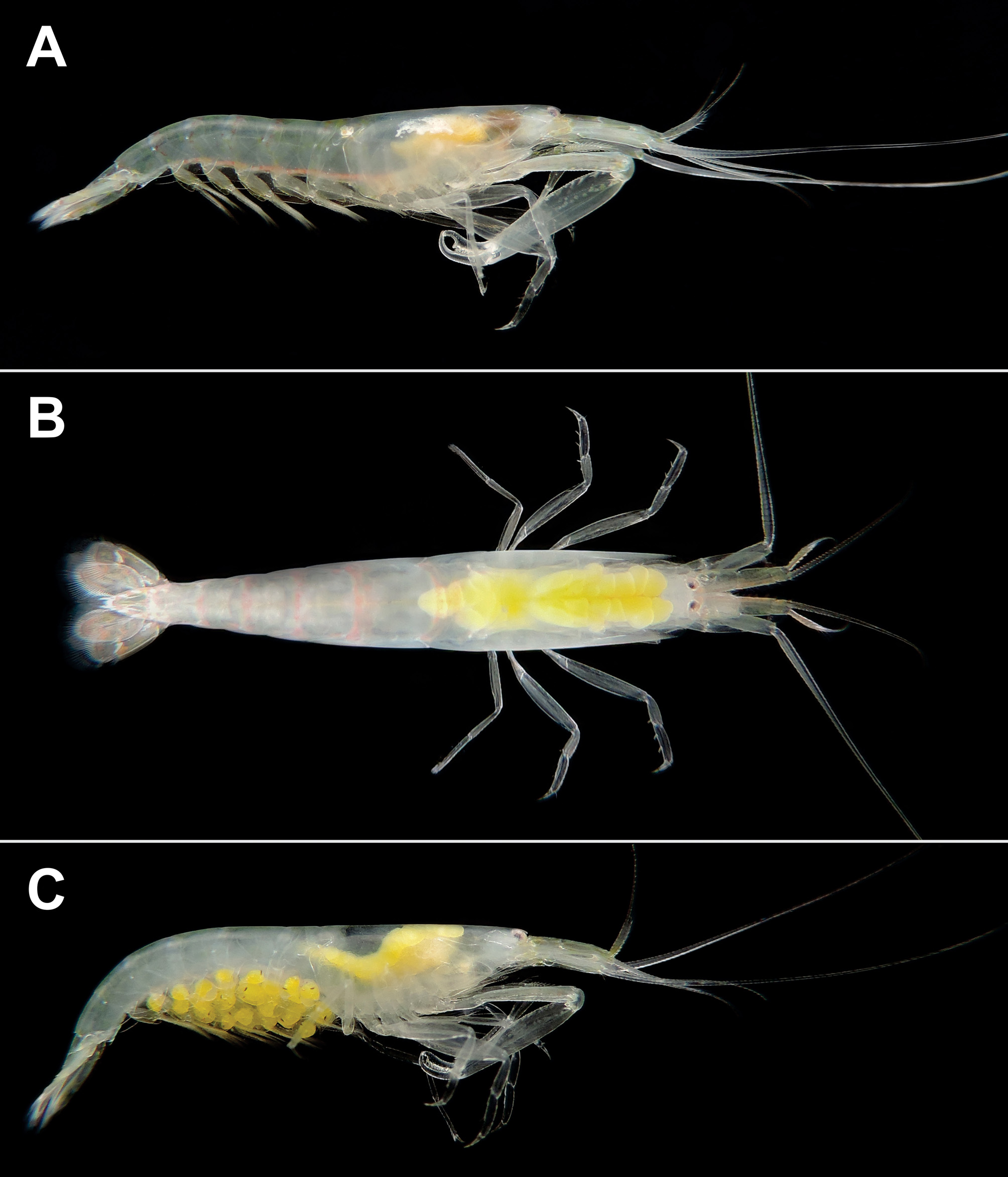

Colour in life. Semitransparent with yellowish or purplish chromatophores, posterior abdominal somites greenish in colour; hepatopancreas greenish or orange in colour; antennular and antennal peduncles and tail fan with reddish or greenish chromatophores; presence of some chromatophores on the merus and carpus; chela colourless ( Figs. 2 View FIGURE 2 A–C); eggs in early stages of development bright green in colour ( Fig. 2C View FIGURE 2 ), and those at an advanced stage of development (close to hatching) semitransparent.

Distribution. Western Atlantic: from North Carolina ( USA) to Venezuela and Brazil, in the states of Pará (present study), Ceará, Paraíba, Sergipe, and Bahia; Eastern Pacific: coast of Colombia ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ).

Ecology. In present study, the Leptalpheus specimens were collected from the burrows of the callichirid “ghost” shrimp, L. siriboia , in a muddy-sandy intertidal zone on the Amazon region, northern coast of Brazil ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A–C). Pachelle et al. (2016) also recorded L. siriboia hosting L. forceps in its burrows in the Brazilian state of Ceará. L. forceps has also been observed living in association with other burrowing shrimps from the families Upogebiidae and Callichiridae ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). However, information on the feeding ecology, behaviour, reproduction, growth, embryonic and larval development of this species is still lacking, and these parameters require further investigation.

Remarks. Based on its morphological similarities with a number of other Leptalpheus species, the alpheid shrimp L. forceps is currently included in an informal species group from the western Atlantic and eastern Pacific coasts, which also includes Leptalpheus mexicanus , Leptalpheus felderi , and a number of other, as yet undescribed species ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). All these species share the presence of a mesial tooth on the ischium of the major cheliped, while the stylocerite does not reach the distal margin of the first segment of the antennule ( Anker et al. 2006b). The actual taxonomic scenario is extremely complex, given that Leptalpheus genus appears to be closely related to the genera Richalpheus Anker & Jeng, 2006 , Amphibetaeus Coutière, 1897 , and Fenneralpheus Felder & Manning, 1986 . In all these genera, the margin of the carapace has no rostrum or orbital teeth, while the stylocerite is more or less compressed onto the first segment of the antennule, the major cheliped is very asymmetrical and is carried folded when unused, and the minor cheliped has a characteristic shape, with a slender merus and elongated fingers ( Williams 1965; Felder & Manning 1986; Anker & Jeng 2006; Anker et al. 2006b; Anker & Dworschak 2007; Marin et al. 2014). Despite these similarities, the genus Leptalpheus is currently considered to be a sister taxon of the genus Fenneralpheus , as supported by the molecular analysis of 16s mtDNA (see Felder et al. 2003, fig. 9).

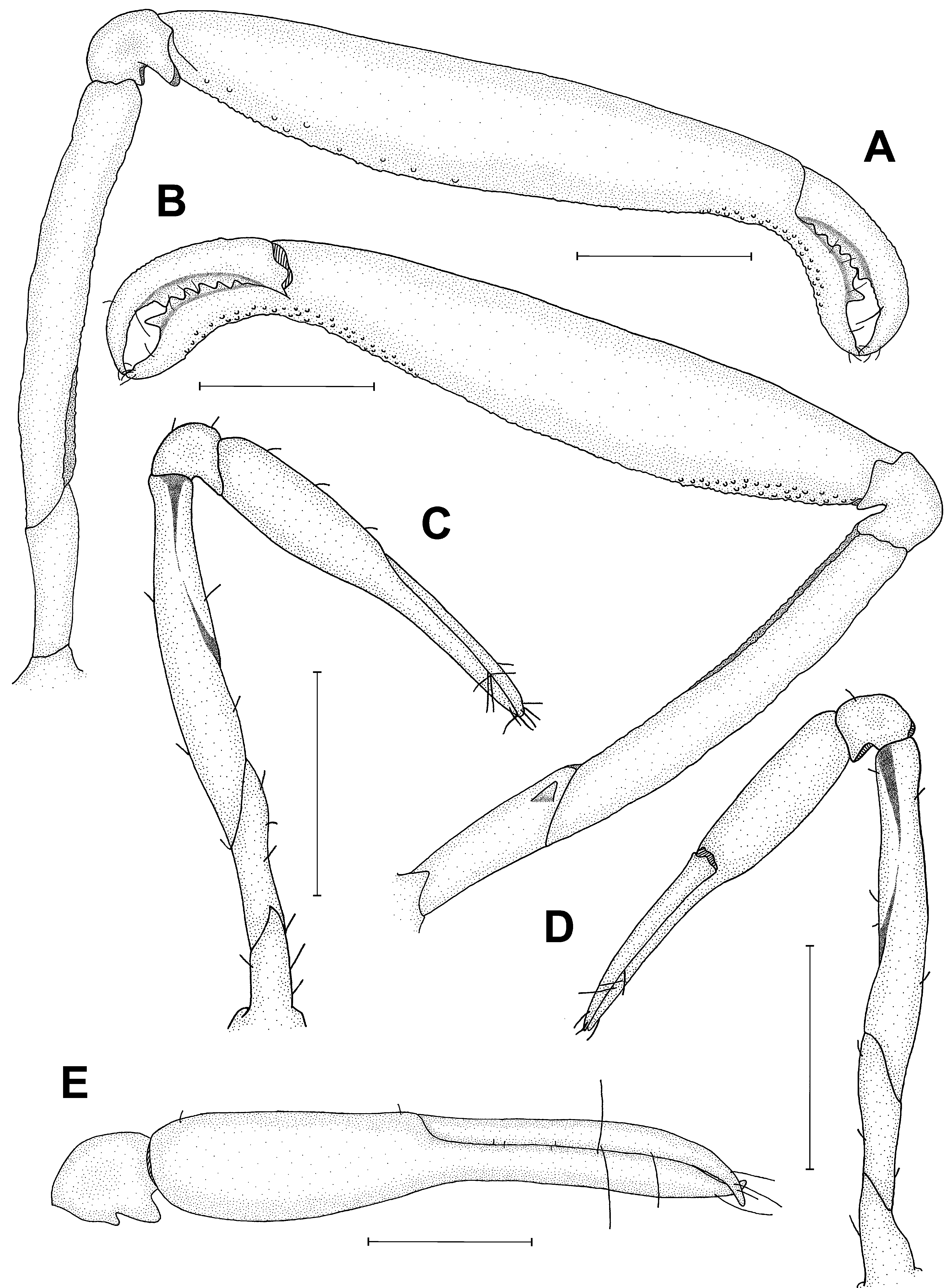

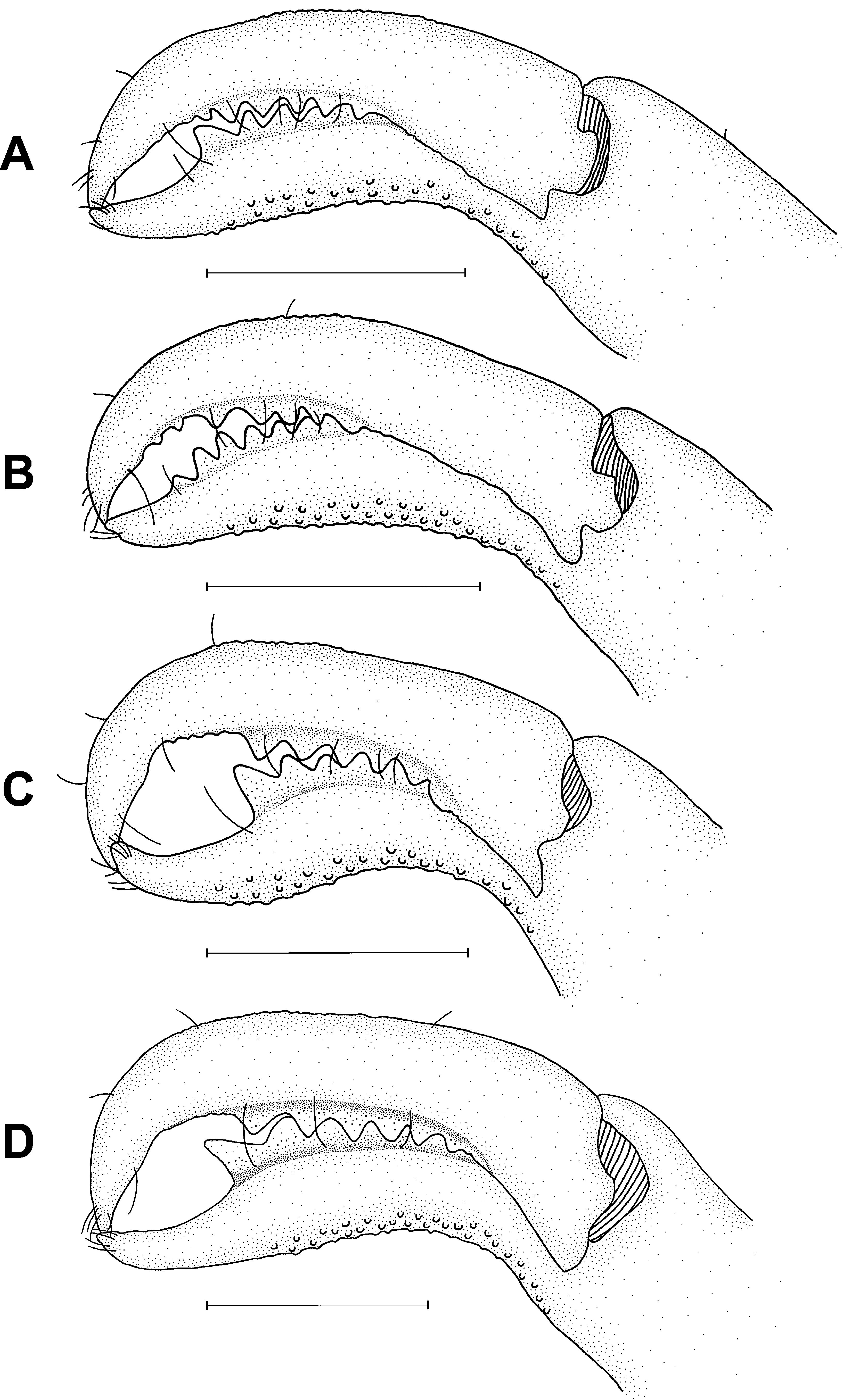

The morphology of the L. forceps specimens from the Ajuruteua Peninsula, Amazon region, is much more similar to that of the specimens of L. cf. forceps from the Costa Rica and Panama described by Anker (2008, 2011) than those of L. forceps from the North Carolina ( USA) described originally by Williams (1965) or the L. aff. forceps from the Brazilian state of Bahia reported by Almeida et al. (2012). The morphological similarities between the Amazonian and Central American specimens are related to the proportion of the articles of the antennule, in particular, the slightly more robust antennular peduncle, the short scaphocerite, which is no longer than half the length of the second antennular peduncle ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 ; Anker 2008, fig. 4A), and the same number of teeth (six or seven) in the major chela ( Figs. 5 View FIGURE 5 , 6 View FIGURE 6 ; Anker 2008, fig. 5H, L). In the present study, furthermore, a caudal filament was observed on each uropodal endopod in specimens of both sexes of L. forceps ( Fig. 3D View FIGURE 3 ), like that described in two males of L. cf. forceps by Anker (2008, fig. 4J), albeit with varying lengths. In the Amazonian L. forceps , however, this structure was absent in most of the individuals analyzed ( Fig. 3E View FIGURE 3 ). The same caudal filament was also observed in one male paratype of L. felderi ( Anker et al. 2006b, fig. 5C), but it was also absent in other specimens of this species, and, when present, it was not as prominent as in L. cf. forceps ( Anker, 2008, fig. 4J). The possible functions of this structure are still unclear and demand further research.

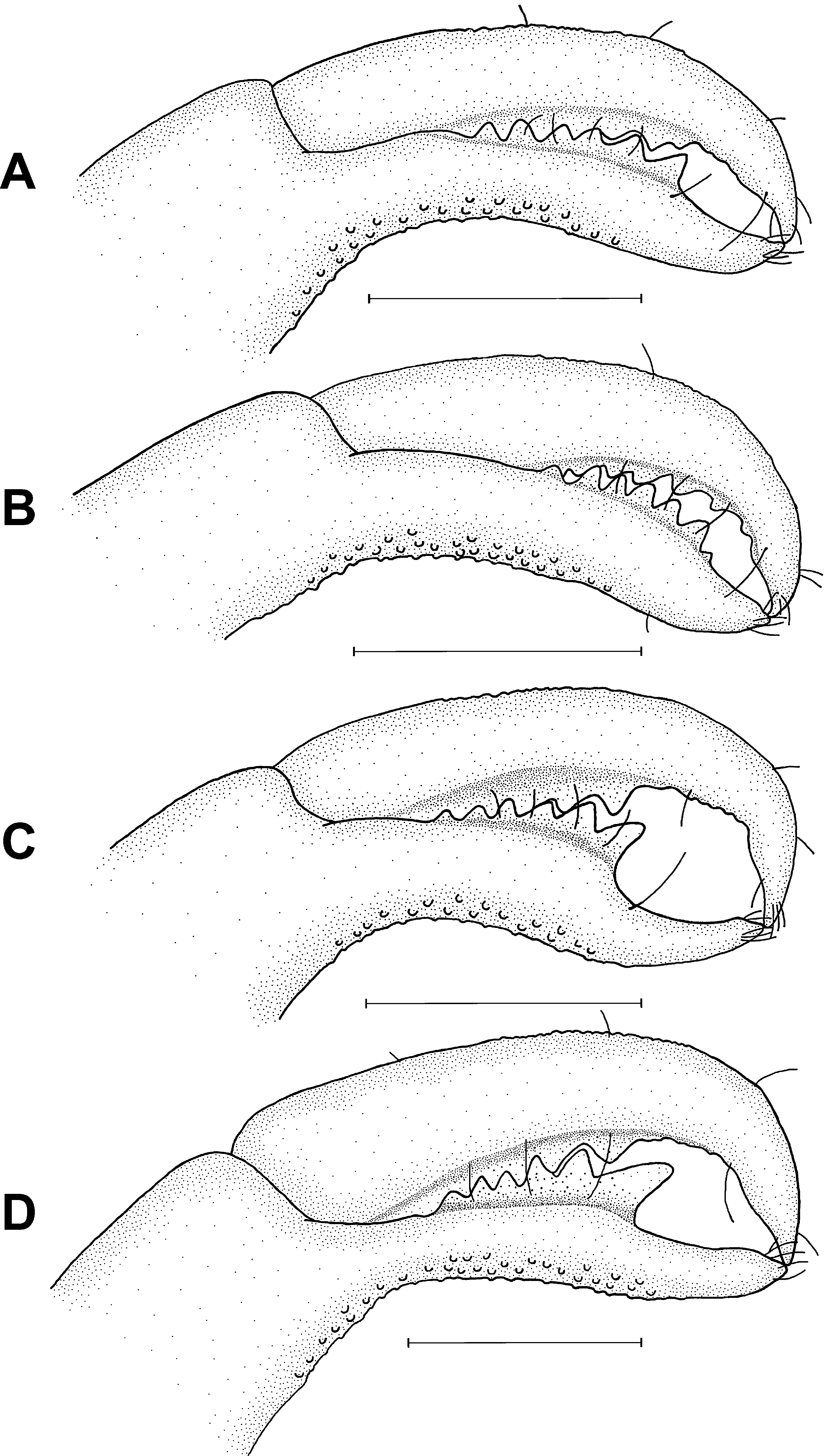

The gap between the fingers of the major cheliped varied considerably in the L. forceps specimens collected in the present study ( Figs. 5 View FIGURE 5 , 6 View FIGURE 6 ). Williams (1965) noted that the fingers of the major cheliped in the females of L. forceps from North Carolina were less widely spaced than those of the males. In the specimens analyzed in our study, however, this gap did not vary systematically between males and females and, therefore, the major cheliped presented fingers with more or less gaping independent of the sex. In addition, four different morphological variations of the major cheliped in L. forceps were identified here, with the most common presenting a more protruding distal tooth and a more widely spaced gap than the others (see Figs. 5C View FIGURE 5 , 6C View FIGURE 6 ). The variation in the fingers gap of the major cheliped of the L. cf. forceps specimens from Costa Rica ( Anker 2008, fig. 5G, F, L) was very similar to that observed here in the Amazonian L. forceps (see Figs. 5A, D View FIGURE 5 , 6A, D View FIGURE 6 ). Also, a male specimen of L. aff. forceps was found in the Brazilian state of Bahia exhibiting the major cheliped with less gaping (see Almeida et al. 2012, fig. 5C), similar to that observed in some specimens collected in the present study (see Figs. 5A View FIGURE 5 , 6A View FIGURE 6 ). It is important to note, however, that the recognition of the variation in the morphology of the cheliped and fingers gap in our Leptalpheus specimens may only have been possible due to the relatively large sample size, in comparison with the studies of Williams (1965), Anker (2008), and Almeida et al. (2012). One additional difference is the variation in the number of teeth (six or seven) of the major chela in the Amazonian specimens analyzed here, in contrast with the six teeth of the type species (see Williams 1965, fig. 1G). The morphological diversity found within the genus Leptalpheus and the L. forceps group clearly requires more systematic investigation, as well as the application of a phylogenetic approach, to identify possible homoplasies or synapomorphies ( Anker 2008).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

InfraOrder |

Caridea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Leptalpheus forceps Williams, 1965

| Rosário, Tayse N., Pires, Marcus A. B., Souza, Adelson S., Fernandes, Marcus E. B., Abrunhosa, Fernando A. & Simith, Darlan J. B. 2020 |

Leptalpheus forceps

| Pachelle, P. P. G. & Anker, A. & Mendes, C. B. & Bezerra, L. E. A. 2016: 13 |

| Anker, A. & Vera Caripe, J. A. & Lira, C. 2006: 685 |

| Williams, A. B. 1984: 101 |

| Williams, A. B. 1965: 192 |