Nesorhinus, Antoine & Reyes & Amano & Bautista & Chang & Claude & De Vos & Ingicco, 2022

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlab009 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7551586 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1B53A12D-1C52-BF40-FC6F-C5BB3446983D |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Nesorhinus |

| status |

gen. nov. |

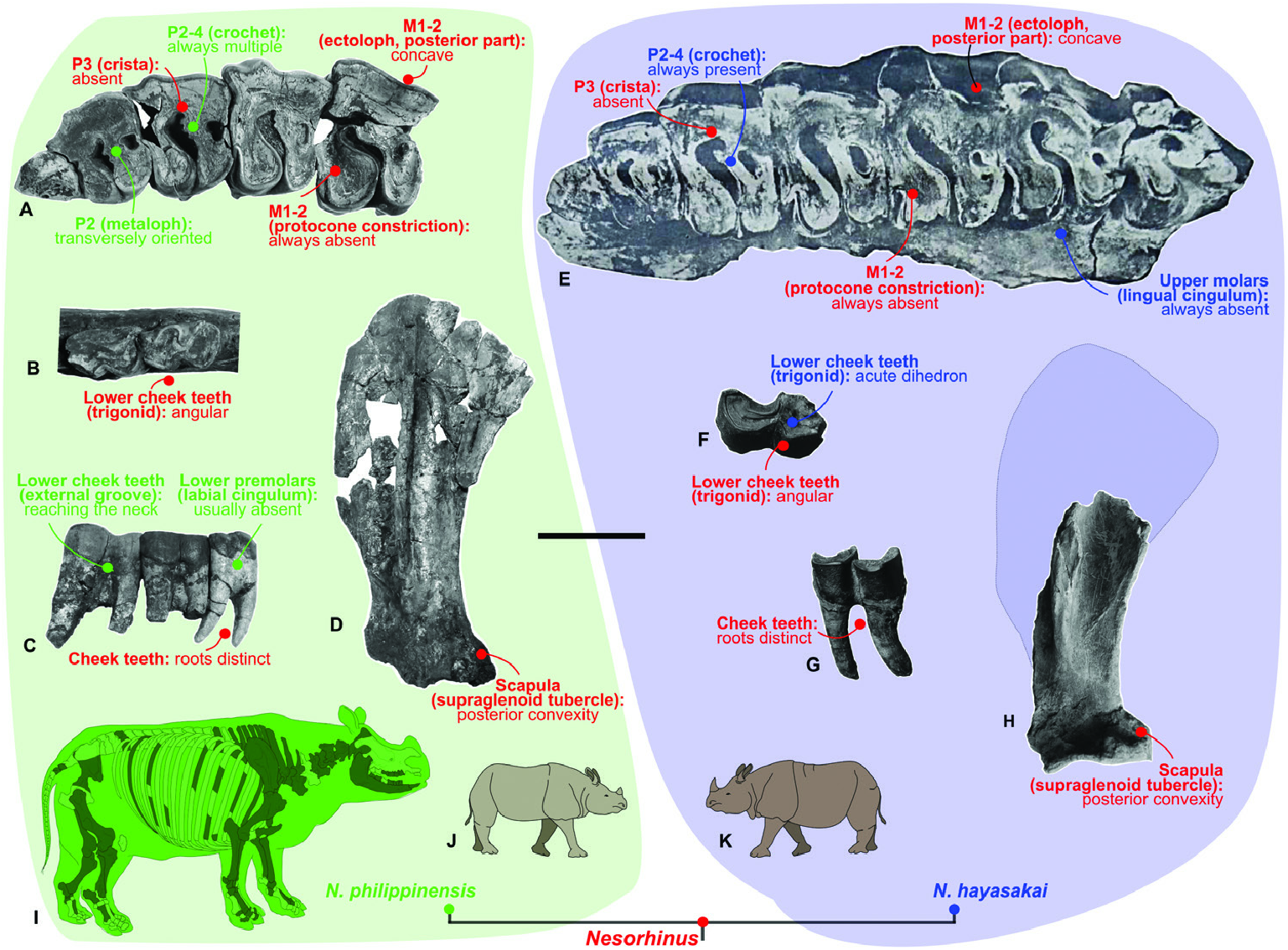

NESORHINUS GEN. NOV.

( FIG. 3 View Figure 3 )

Zoobank registration: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:CE90CF70-64F7-4665-AD9C-367B4D662372 .

Etymology: From the ancient Greek n ễ sos (νῆσος, island) and the suffix - rhinus (from Greek ῥίς, rhis, nose), frequently used for designating rhinocerotid genera.

Type species: Nesorhinus philippinensis ( von Koenigswald, 1956) comb. nov. See Supporting Information for further details.

Referred species: Nesorhinus hayasakai ( Otsuka & Lin, 1984) comb. nov.

Diagnosis: Medium-sized rhinocerotines, characterized by roots fully isolated on upper cheek teeth, a crochet usually present on P2-4, a crista absent on P3, a protocone constriction always absent and a posterior half of the ectoloph concave on M1-2, a trigonid angular in occlusal view on lower cheek teeth and a posterior supraglenoid tubercle convex and salient on the scapula. Differing from representatives of both Dicerorhinus and Rhinoceros in having no cement on cheek teeth, a protocone joined to the ectoloph on P2, a proximal border of the third metatarsal sigmoid in anterior view, and intermediate reliefs high and sharp on metapodials. Distinct from Rhinoceros in possessing a protocone and a hypocone equally developed on P2 and in having no anterior trochlear notch on the astragalus. Further differing from Dicerorhinus in possessing a V-shaped lingual opening of the posterior valley on lower premolars.

Geographic and stratigraphic range: Early and Middle Pleistocene of Luzon Island, Philippines, and of Taiwan Island ( von Koenigswald, 1956; Otsuka & Lin, 1984; Ingicco et al., 2018).

Description: See morpho-anatomical characters in Supporting Information, Text S3. Even if nasal or frontal bones are not recognized in the current hypodigm of N. philippinensis and N. hayasakai , Nesorhinus was most probably one-horned, i.e. with a nasal horn and no frontal horn, as inferred by the topology of the consensus tree: this is the ancestral condition in Rhinocerotina and Rhinoceroti, retained in Rhinoceros . According to the most-parsimonious topologies, a frontal horn was acquired independently in Diceroti and Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (and perhaps also in D. fusuiensis ), which is in full agreement with the most recent genomic phylogenies.

Body mass, as predicted from regressions on upper and lower teeth, but also on limb bones, with consistent results, is estimated at 998–1670 kg for Nesorhinus (Supporting Information, Table S5). Nesorhinus philippinensis , documented at the Kalinga site by at least two individuals similar in size, was the smallest and lightest species. Body weight ranged between 1025 and 1185 kg (mean: 1103 kg) based on dental predictors and 998–1140 kg (mean: 1069 kg) based on postcranial predictors, which falls between the known ranges of the Sumatran and Javan rhinos, the smallest of the extant rhinos. Nesorhinus hayasakai was somewhat heavier, with more variable weight estimates based on teeth (mean: 1263 kg; range: 1018–1670 kg; Supporting Information, Table S3), and a slightly heavier estimate based on radius (1306 kg; Supporting Information, Table S5). A shoulder height of c. 1.23–1.30 m was estimated for N. philippinensis through comparison of forelimb dimensions with recent rhinos (mean: 1.26 m). This estimate is similar to the smallest Javanese rhino individuals and to average Sumatran rhino individuals (Supporting Information, Tables S6, S7). A marginally higher stature (c. 1.31 m) is inferred for N. hayasakai (see Supporting Information, Tables S6, S7). Nevertheless, comparison of skeletal proportions shows that N. philippinensis was particularly slender-limbed, with the notable exception of the scapula and the metapodials. Its gracility indices are closely similar to those of the most gracile living rhinoceros, i.e. Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Supporting Information, Table S8; Figs S5, S6). Within Nesorhinus , N. philippinensis was also much more slender-limbed than N. hayasakai , which is further consistent with significantly lighter body mass estimates based on radius (998 vs. 1306 kg, respectively; Supporting Information, Table S5). This discrepancy may be related either to interindividual variability [e.g. sexual dimorphism – although it seems to be exaggerated for a rhinocerotine ( Guérin, 1980)], or to a secondary adaptation to the unbalanced insular environment of the Philippines (Supporting Information, Table S8) with respect to mainland assemblages. Strikingly, the scapula of N. philippinensis is neither particularly spatulate nor elongated. Its gracility equals that of Diceros bicornis and it is intermediate to the living Rhinoceros species, while Dicerorhinus sumatrensis has by far the most robust scapula (Supporting Information, Table S8).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.