Psittacula Cuvier, 1800

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1513.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:35934778-7619-4BD0-8D0C-A5817B17EE27 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/243B2E20-FFFC-6112-A087-FF6CFCCDF979 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Psittacula Cuvier, 1800 |

| status |

|

Genus Psittacula Cuvier, 1800 View in CoL :

table with no pagination.

Etymology: From Latin Psittacus meaning parrot, and - ula, a diminutive suffix.

Diagnosis: Cranium moderately dorso-ventrally flattened, craniofrontal hinge medially concave, processus postorbitalis long but not fused to the lacrimal; mandible comparatively broad; diameter of nares greater than the width of internarial septum; tomium distinctly notched, with a concavity that abruptly indents the cranial border, creating a single tooth; spina externa prominent with an indistinct distal division. Species of Psittacula are large-billed, long-tailed parrots, the tail graduated with the attenuated central feathers longest. Red bills and neck rings are also common to the majority of taxa in this genus (see Forshaw 1989).

Thirioux’s Grey Parrot Psittacula bensoni (Holyoak, 1973) , new combination

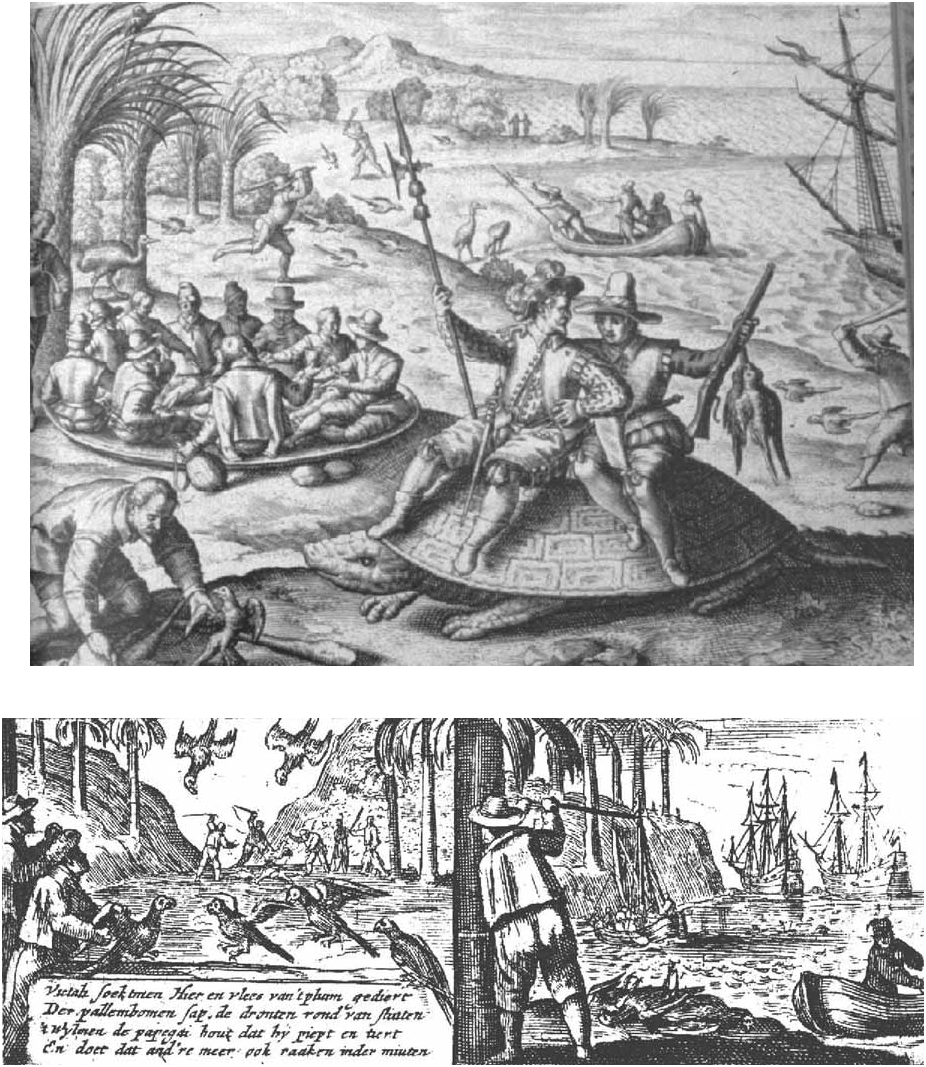

Grauwe papegayan, Begin en de voortgangh 1646:30; Soete-boom 1648: 20, pl. 20v., with note.

Lophopsittacus bensoni Holyoak, 1973: 417 .

Holotype: Although Holyoak (1973a:417) clearly designated mandibular symphysis UMZC 18/Psi/37/a/1 (now UMZC 577a) as the holotype and illustrated it in dorsal view (pl. 8a), he erroneously labeled a mandible in ventral view (pl. 8b) as also being the holotype, whereas the illustration actually shows a different specimen ( Cowles 1987; Hume, pers. obs.). The latter (now UMZC 577b) is to be included among the various paratypes illustrated by Holyoak and listed below.

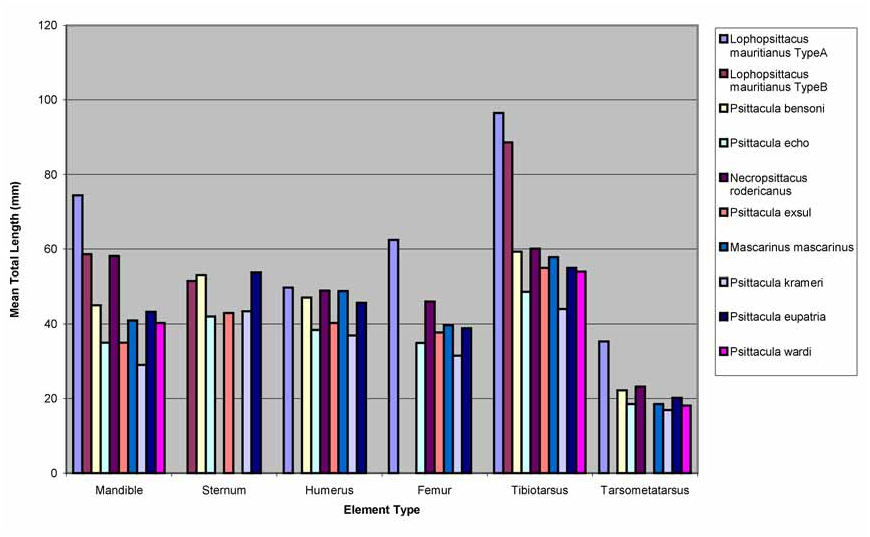

Measurements: See Appendix 3, tables 1–11.

Type locality: Le Pouce, Mauritius

Distribution: Mauritius and possibly Réunion Island, Mascarenes (see below)

Etymology: In honour of C. W. Benson (1909–1982).

Paratypes: Subfossil material collected from Le Pouce, Mauritius. The second symphysis of lower mandible (UMZC577b) (Holyoak pl. 8b); upper mandible (UMZC 577) (Holyoak pl. 8c, 8d and 8e); palatine (UMZC 577 (L)) (Holyoak pl. 8f and 8g); tarsometatarsus (UMZC 577(R) (Holyoak pl. 8i and 8o); (UMZC 577(R) (Holyoak pl. 8l and 8r); (UMZC 577(R) (Holyoak pl. 8m and 8s); (UMZC 577(Ld) (Holyoak pl. 8k and 8q). Two of the tarsi assigned by Holyoak to ‘ Lophopsittacus ’ bensoni (UMZC 577) (Holyoak pl. 8h and 8n) and (UMZC 577) (Holyoak pl. 8j and 8p) are referable to another species (see Psittacula echo ).

Referred material: Subfossil material collected from Le Pouce, Mauritius; mandible UMZC 577(d); UMZC 577 (d); rostrum UMZC 577 (d); UMZC 577(d); palatine UMZC 577(L); sternum UMZC 599(p); UMZC 599(p); UMZC 599(p); coracoid MNHN MAU566(L); MNHN MAU579(R); MNHN MAU576(L); humerus UMZC 596(L); UMZC 596(L); UMZC 596(R); UMZC 596(Rp); UMZC 600(Lp); UMZC 596(R); UMZC 596(L); MNHN MAU562(L); carpometacarpus MNHN MAU515; femur MNHN MAU556(R); MNHN MAU540(R); MNHN MAU549(L); tibiotarsus MNHN u/c(R); MNHN u/c(L); MNHN MAU514(R); MNHN MAU550(R); tarsometatarsus UMZC 594(Lp); UMZC 594(Ld); UMZC 594(R) (juv); MNHN u/c(L) (juv); MNHN u/c(R); MNHN MAU593(R); MNHN MAU368(R); MNHN MAU366(L); MNHN MAU527(R); MNHN 508(R); MNHN 553(L); MNHN 524(L).

Diagnosis: This species was previously placed in the genus Lophopsittacus (Holyoak 1973; Cowles 1987), but re-examination of the fossils now available indicates that it belongs in the genus Psittacula . Differs from Lophopsittacus and Psittacula echo by the following suite of characters: rostrum approximately 29% larger in total length than in P. echo ; rami of mandible more laterally deflected indicating that this species had a comparatively broad bill; in sternum spina externa less anteriorly projected; incisura costalis more pronounced with the 5 th deeply excavated; one anteriorly situated foramen pnematicum present; sulcus articularis coracoideus distinctly unequal; in humerus, processus flexorius distinct, emphasising the sulcus humerotricipitalis with fossa olecrani comparatively wide; crista bicipitalis merges sharply with the shaft distally, proximal

fossa pneumotricipitalis circular and sulcus transversus deeply excavated; processus supracondylaris dorsalis prominent and a small depression occurs proximal to the condylus dorsalis; tuberculum ventrale deflected mediolaterally and distolateral edge of crista bicipitalis not angled as it merges with the shaft; in coracoid, processus procoracoideus short with shallow cotyla scapularis, and projects further medially; in tarsometatarsus, two canals formed by crista intermediae hypotarsi shallow; two foramina vascularia proximalia present. In life, P. bensoni was described as a long-tailed grey parrot.

Description and comparison: See Appendix 2b.

Remarks: As specimens of P. bensoni are known only from the fossil collections of Etienne Thirioux and the species was described in life as grey, to avoid further confusion with the green Psittacula echo , the English name Thirioux’s grey parrot, honouring the collector and indicating the colouration, is proposed here. Holyoak (1973a) diffidently placed bensoni in Lophopsittacus and he separated it from Lophopsittacus mauritianus on size alone, although there are discernible generic differences that he did not discuss. The species is clearly derived from Psittacula stock and is similar to Psittacula eupatria but larger and more robust in some elements ( Fig. 19 View FIGURE 19 ). It also appears to have been atypical in colouration, being all grey, as the majority of species of Psittacula are green or partially green.

The the ease with which P. bensoni could be caught in abundance is reported by Willem van West-Zanen, who visited Mauritius in 1602. His account, published in 1648 ( Soete-boom 1648), included the only known drawing of this species ( Fig. 7b View FIGURE 7 ) and described the first encounter West-Zanen’s crew had with parrots:

….some of the people went bird hunting. They could grab as many birds as they wished and could catch them by hand. It was an entertaining sight to see. The grey parrots are especially tame and if one is caught and made to cry out, soon hundreds of the birds fly around ones’ ears, which were then hit to the ground with little sticks. Also just as tame are the pigeons and turtle doves, that let themselves be caught easily…..[my translation].

Admiral Steven van der Hagen visited Mauritius in 1606 and 1607 (Begin en de voortgangh 1646; Barnwell 1948). Der Hagen mentions again the ease with which the birds could be caught and that the catching of a single parrot ultimately could lead to the entire flock being taken:

During all our time there, we lived on turtles, dodos, pigeons, doves, grey parrots, and other game, which we caught in the woods with our hands. Besides their usefulness to us, there was also much amusement to be got from them. Sometimes when we had caught a grey parrot, we made it call out, and at once hundreds more came flying around, and we were able to kill them with sticks [ Barnwell 1948:17].

Thirioux’s grey parrot was particularly sought after as game. Despite this persecution, grey parrots remained reasonably common until the 1750s, but the population must have crashed shortly afterwards as Cossigny’s account in 1764 ( Cheke 1987) is the last time that they were mentioned. It was during the 1730s that the French instigated large-scale slash and burn forest clearance ( Toussaint 1972), which undoubtedly had a serious effect on cavity-nesting species such as parrots.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.