Microcebus murinus (J. F. Miller, 1777)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6639118 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6639130 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/253C87A7-FFE9-DB57-FFCF-FE43AFD9F741 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Microcebus murinus |

| status |

|

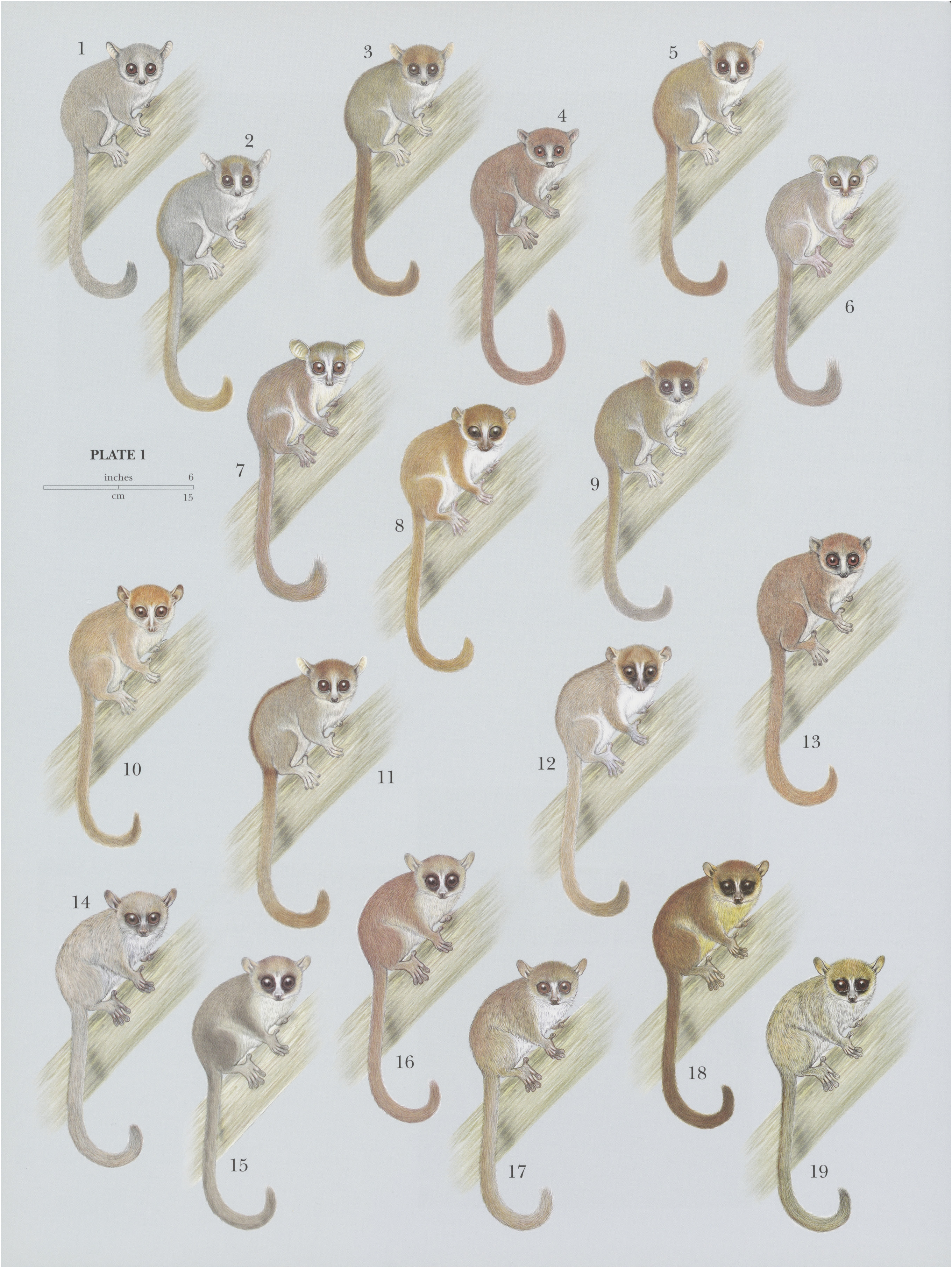

1. View Plate 1: Cheirogaleidae

Gray Mouse Lemur

Microcebus murinus View in CoL

French: Microcebe murin / German: Grauer Mausmaki / Spanish: Lémur ratén gris

Other common names: Lesser Mouse Lemur

Taxonomy. Lemur murinus J. F. Miller, 1777 ,

Madagascar, province of Toliara, S Andranomena, 20 km NNE of Morondava (20° 09'S, 44° 33 LE).

Although currently no subspecies recognized, it is believed that further study may reveal the existence of several distinct forms. Individuals from the Angavo escarpment, for example, are entirely gray except for some contrasting reddish tones on the head and around the eyes. Monotypic.

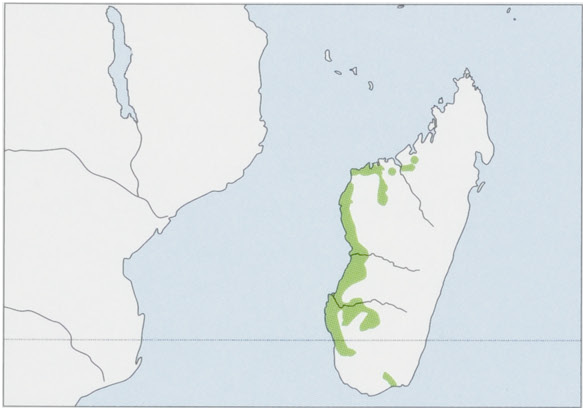

Distribution. W & SE coastal Madagascar from below the Onilahy River (perhaps as far as Tsimanampetsotsa National Park in the S to Ankarafantsika National Park in the N); a disjunct population also occurs in the SE up to the littoral forests of the Mandena Conservation Zone. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 12-14 cm, tail 13-14.5 cm; weight 60 g. The Gray Mouse Lemur is a large mouse lemur. Although there is no sexual dimorphism in the Gray Mouse Lemur ,there is a definite seasonal swap between males and females with regard to body weight. Males are consistently heavier than females during the reproductive season, with the opposite during the rest of the year. The dorsal coat is brownish-gray with various reddish tones, flanks are light gray to beige, and ventral fur has discrete dull beige or whitish-beige patches along parts of the belly. A pale white patch occurs above the nose and between the eyes; some individuals have dark orbital markings. Furred portions of hands and feet are off-white. Ears are long and fleshy compared with shorter, more concealed ears of the Rufous Mouse Lemur ( M. rufus ). The tail is barely longer than the head-body length.

Habitat. Primary and secondary lowland tropical dry forest and subarid thorn scrub, as well as semi-humid deciduous, gallery, spiny, and eastern littoral forest from sea level to 800 m. The Gray Mouse Lemurlives in the fine-branch niche, which is a dense foliage zone with large numbers of fine branches and narrow lianas. When living in sympatry, the Gray Mouse Lemur prefers to sleep in tree holes, and the Golden-brown Mouse Lemur ( M. ravelobensis ) mostly sleeps on branches and lianas and in vegetation tangles. Females tend to share nests with several conspecifics, but males tend to sleep alone. Females in sleeping groups may save energy by reducing their resting metabolic rate. Decreased habitat quality may have adverse effects on population dynamics. Fewer available tree holes in secondary forests result in fewer opportunities to save energy through periods of torpor and may increase levels of stress and mortality. The Gray Mouse Lemur is sympatric with the Gray-brown Mouse Lemur ( M. griseorufus ) in some areas of the south-west, the Golden-brown Mouse Lemur in the Ankarafantsika region of the north-west, Peters’s Mouse Lemur ( M. myoxinus ) in Tsingy de Namoroka and Baie de Baly national parks, and Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur (M. berthae ) in the Kirindy Forest. It also may be sympatric with the Tavaratra Mouse Lemur (M. tavaratra ) in the Ankarana region.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Gray Mouse Lemur is varied, consisting largely of invertebrates (particularly beetles, as well as moths, praying mantids, fulgorid bugs, and spiders) but also fruits, flowers, gums, nectar, exudates, and small vertebrates (including tree frogs, geckos, and chameleons). Leaves of Uapaca (Phyllanthaceae) are also consumed. An interesting food source are the excretions from the hemipteran larvae, Flatida coccinea. These larvae group together on tree branches to resemble flowers, a form of cryptic mimicry. They are also most abundant during the dry season when other food sources of the Gray Mouse Lemur are absent. Availability of these insect larvae affects distribution of females, in that the insects are more abundant in the forest edge rather than the interior; it has been shown that female Gray Mouse Lemurs will shift their ranging behavior in the dry season to the forest edge to feed on the excretions. When living in sympatry, the Golden-brown Mouse Lemur seems to rely more on hemipteran excretions than the Gray Mouse Lemur , which includes more fruits in its diet.

Breeding. The Gray Mouse Lemur has a multimale-multifemale mating system. Females become sexually receptive every 45-55 days and usually have 2-2 estrous cycles. In capuvity, after the breeding season has started, the first estrus is strongly synchronized within the population, but subsequent cycles are not. Estrous synchrony of captive females was enhanced by the presence of sexually active males. During the breeding season, males increase in size, and theirtestes enlarge to eight times their original size. Male Gray Mouse Lemurs deposit sperm plugs during copulation. Usually two (sometimes one, three, or even four) hairless, rudimentary young are born after a gestation ofjust 54-68 days. The female can have two litters per year in captivity. Captives weigh 4-6-7-2 g at birth. Eyes are open within two to four days, and infants are born capable of clinging. Infants are carried until six weeks old, but they never ride on the fur of the mother. In captivity, infant Gray Mouse Lemurs are first seen out of the nest at three weeks old and first eat solid foods at one month old. Allomothering is seen in this species, with individual females nursing and grooming infants that are not their own. Play starts at 10-13 days, as does the adult sleeping posture, in which the individual curls on its side as opposed to the infant posture of sleeping flat on their ventrum. Wild Gray Mouse Lemurs start leaping at three weeks of age. Weaning occurs at about six weeks. Young are bare on the abdomen and have a gray stripe down their back. Individuals may live up to 18 years in zoos.

Activity patterns. The Gray Mouse Lemur is nocturnal and arboreal. Studies at Ankarafantsika National Park indicate that individuals may take shelter in three to nine different tree holes within their home ranges, and they remain in a given shelter for several days in succession. Two or more females will form breeding groups and raise their young cooperatively. Activity patterns appear to differ between populations and sexes. Males and females at Ankarafantsika exhibit daily, rather than seasonal, torpor. In the Kirindy Forest, both sexes show the same daily torpor, but most adult females also enter torpor for significant periods, while males remain active during these same periods. Males become extremely active several weeks before the females emerge from their torpor.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Recent studies of social behavior confirm that male home ranges tend to be twice as large as those of females and also increase in size during the mating season. Home ranges of both sexes overlap (those of femalesless so than those of males), and home ranges of all members of a “neighborhood” overlap in a central area. Recent genetic studies of populations at Kirindy Forest suggest that females arrange themselves spatially in clusters ofrelated individuals, while males tend to emigrate from their natal groups. Home ranges of Gray Mouse Lemurs using torpor in the dry season are smaller than those of individuals remaining normothermic.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red Last. Loss of habitat for slash-and-burn agriculture and live capture to supply the local pet trade are the two most significant threats to the Gray Mouse Lemur —the latter being more prominent in the southern and northern parts ofits distribution. Nevertheless, it remains one of the most widespread and abundant species of lemurs. It occurs in six national parks (Andohahela, Ankarafantsika, Baie de Baly, Isalo, Tsingy de Namoroka, and Zombitse-Vohibasia), six special reserves (Andranomena, Ankarana, Bemarivo, Beza-Mahafaly, Kasijy, and Maningoza), Berenty Reserve, and other privately-protected forests in the Mandena Conservation Zone, east of Tolagnaro (= Fort-Dauphin). It also is found in the Kirindy Forest (part of the Menabe-Antimena Protected Area).

Bibliography. Buesching et al. (1998), Colas (1999), Corbin & Schmid (1995), Dammhahn & Kappeler (2005), Eberle & Kappeler (2002, 2003, 2004b, 2006), Eberle et al. (2007), Fietz (1998), Fleagle (1999), Ganzhorn & Randrianamalina (2004), Ganzhorn & Schmid (1998), Génin (2003), Glatston (1979, 1986), Goodman et al. (1993a, 2002), Groves (2001), Kappeler & Rasoloarison (2003), Martin (1972, 1973, 1975), Mittermeier et al. (2006, 2010), Nicoll & Langrand (1989), Pages-Feuillade (1988), Perret (1990, 1992, 1995, 1998), Petter et al. (1977), Radespiel (2000), Radespiel & Zimmermann (2001a, 2001b), Radespiel et al. (1998, 2003b), Rasoazanabary (2001, 2004), Rasoloarison et al. (2000), Schmid (1998), Schmid & Kappeler (1998), Schmid & Speakman (2000), Schwab (2000), Smith & Leigh (1998), Thorén et al. (2011), Van Horn & Eaton (1979), Wimmer et al. (2002), Yoder et al. (2002), Zimmermann (1995, 1998).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Microcebus murinus

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Lemur murinus

| J. F. Miller 1777 |