Kayentasuchus, 2002

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00026.x |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5106331 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/26418E48-FF8E-FFB1-FF42-FF42FC95147C |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Kayentasuchus |

| status |

sp. nov. |

KAYENTASUCHUS WALKERI SP. NOV.

Etymology. In memory of Alick D. Walker for his many contributions to our understanding of Sphenosuchus and other archosaurs.

Holotype. University of California Museum of Palaeontology ( UCMP) 131830, a nearly complete but fragmented skeleton including an incomplete skull with articulated mandibular rami, articulated trunk region, articulated right ilium and femur, and other as yet unprepared postcranial bones.

Type horizon and locality. Near the middle of the Kayenta Formation (Glen Canyon Group) in the ‘silty facies’ of that unit ( Clark & Fastovsky, 1986). Badlands at Willow Springs, Rock Head 7.5 Minute Quadrangle, NE Arizona, USA. Age: Early Jurassic ( Sues et al., 1994).

Diagnosis. Anterior process on maxilla projecting into well-developed, slit-like recess between premaxilla and maxilla. Outline of antorbital fenestra forming equilateral triangle. Squamosal descending along lateral edge of paroccipital process. Elongate mandibular symphysis with only minimal involvement of splenial. Dentary without enlarged anterior caniniform tooth and lacking teeth at anterior tip. Shares with Crocodyliformes presence of a groove along lateral edge of squamosal on dorsal surface.

SKULL

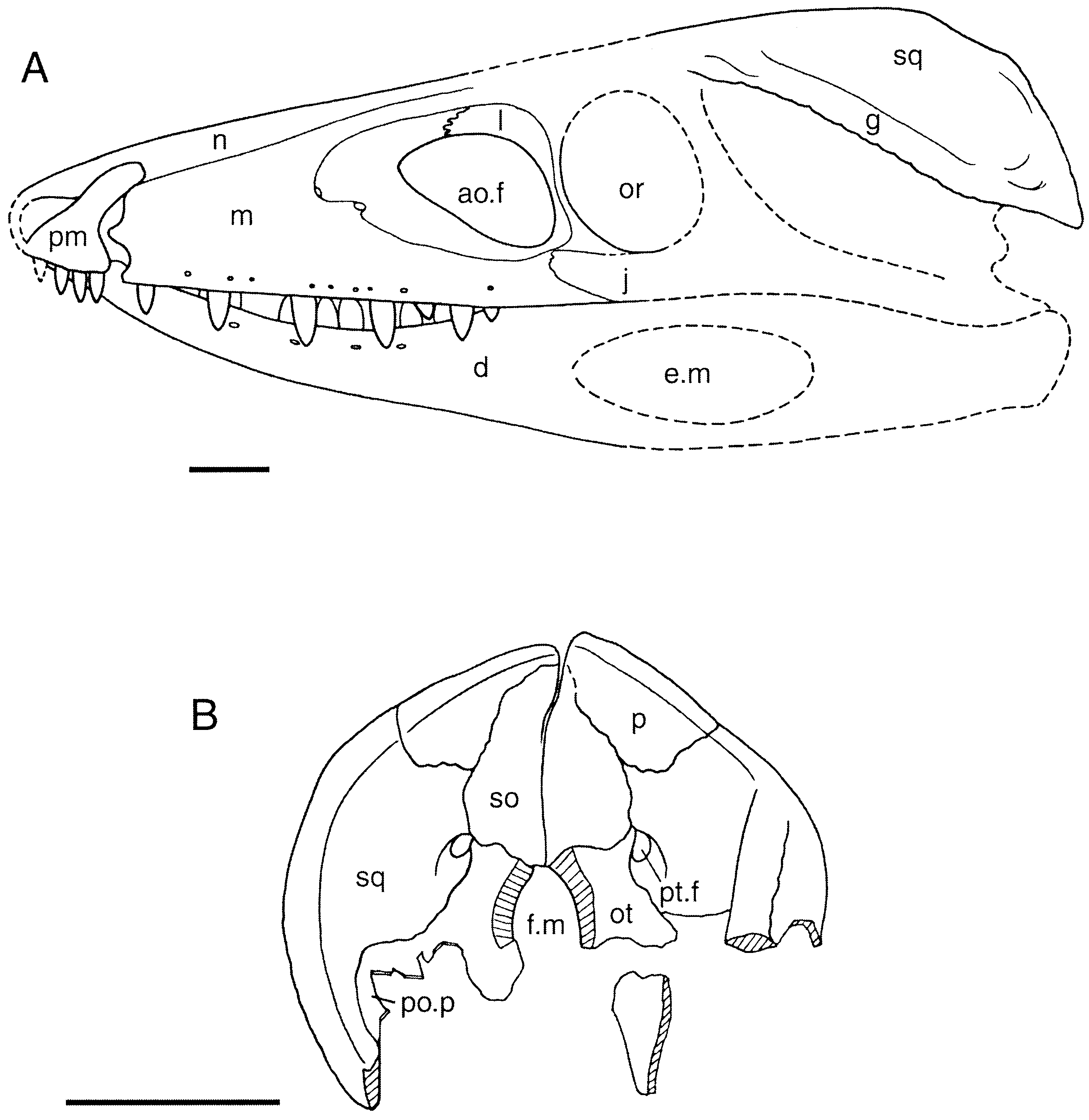

The skull of the specimen ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 4 View Figure 4 ) was compressed laterally during fossilization but otherwise appears undistorted. It broke into several fragments during excavation. The left side of the rostrum is wellpreserved and intact, and is preserved in articulation with the left dentary. The right nasal is preserved with this piece, but the fragmentary right maxilla, premaxilla and dentary and a large fragment of the frontals were recovered separately. The posterior portions of the right and left mandibular rami are also preserved separately. The dorsal part of the braincase and skull roof have been assembled from individual fragments into right and left halves, preserving most details; the ventral part of the prootic and part of the basisphenoid are preserved on the right side only.

The snout ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ) is relatively deep and narrow; even allowing for distortion, it is at least four times higher than wide at the level of the antorbital fenestra. It is comparable in length to Sphenosuchus ( Walker, 1990) and Dibothrosuchus ( Wu & Chatterjee, 1993) and shorter than in Pseudhesperosuchus ( Bonaparte, 1972a) and Terrestrisuchus ( Crush, 1984) . The external nares are terminal and laterally directed. They are divided by a bony bar composed of the nasals and premaxillae (although the premaxillary portion is no longer preserved). Each naris narrows posterodorsally and thus has a slightly oval outline.

An antorbital fenestra is present just anterior to the orbit. It forms a roughly equilateral triangle in outline, with a vertical posterior margin, an horizontal dorsal edge, and an oblique anteroventral margin; the dorsal edge descends to a slight degree anteriorly. The maxilla forms the ventral margin, the lacrimal the posterior, and the two bones meet midway along the dorsal edge; the jugal may enter into the posterior margin of the fenestra, but, if this is indeed the case, it forms only a very small part of that margin. The fenestra, which is about one third the length of the maxilla, is relatively shorter than in Saltoposuchus and Pseudhesperosuchus , but is similar in length to the opening in Sphenosuchus and Dibothrosuchus . Its shape differs from that in the latter, which is more nearly circular, and those of the other three, which are more elongate and oval. A fossa is present in the maxilla anterior to the fenestra.

The squamosals are broadened to form a ‘skull table’ as in crocodyliforms, but, unlike the flat surface of crocodyliform squamosals, that of Kayentasuchus bends ventrally lateral to the quadrate and faces laterally. This may be due to some extent to lateral compression during fossilization, but a ridge along the edge of the occiput at the bend in the squamosal indicates that the bend is natural.

The supratemporal fenestrae are relatively elongate, similar in length to those of other sphenosuchians except for Dibothrosuchus , in which the fenestrae are shorter. The fenestrae of Kayentasuchus are much longer than wide, and although this has been accentuated by the lateral compression of the specimen the original dimensions could not have been significantly different from the observed condition.

The post-temporal fenestra is small but is not absent (as in Dibothrosuchus ). It lies at the junction of the squamosal, parietal, otoccipital, and supraoccipital. This area is crushed on the better preserved left side of the skull, but the smooth ventral edge of the fenestra is present on the right side. On the left side the squamosal appears to form a groove which enters the lateral edge of the fenestra, but this may be due to crushing.

The surfaces of most of the skull bones, with the exception of the frontal and squamosal, are smooth and devoid of sculpturing. The dorsal surface of the frontal bears weakly developed pitting along the midline. The squamosal is rugose near its lateral edge. The sculpturing composed of small pits and grooves typical of crocodyliform cranial bones is absent.

The premaxilla is a small and slender bone forming most of the border of the external naris ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). A slender posterodorsal process overlies the nasal and maxilla in what appears to be a weak suture behind the naris, rather than abutting against them as in crocodylians. The body of the premaxilla forms the anterior edge of a laterally open notch between it and the maxilla; this edge is gently convex posteriorly, and the premaxilla and maxilla do not meet below the notch. A process must have ascended from the anterior part of the premaxilla near the midline to form the ventral half of the internarial bar, but it has been broken away. The premaxillae meet only at the tip of the rostrum and do not meet posterior to the incisive foramen, so they do not form part of the secondary bony palate.

The nasals form the dorsal surface of the snout between the naris and the frontals. Each extends anteriorly to form the posterodorsal half of the internarial bar, although the tips are broken off. The nasal borders the maxilla and lacrimal along their medial edges, and this contact is straight. Between the level of the antorbital fenestra and the nares, the lateral part of the nasal is bent ventrolaterally and faces dorsolaterally. A longitudinal ridge occurs where the bone bends. More posteriorly, the entire bone faces dorsally and meets the frontal at the level of the anterior end of the orbit. It presumably also contacted the prefrontal in this region, but neither prefrontal has been preserved on the rostral fragment. The nasal does not form any part of the fossa associated with the antorbital fenestra.

The maxilla forms most of the facial region of the snout as well as a short secondary bony palate ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Its facial portion is vertical. The length of the maxilla is more than twice its maximum height. It is lower anteriorly and gradually increases in depth posteriorly. The combined length of the antorbital fossa and fenestra is approximately one-half that of the maxilla. The fossa has the same shape as the fenestra but is longer anteriorly and shorter posteriorly. The anterior end of the fossa narrows to a rounded end opposite the sixth tooth. The anterior tip of the fossa enters into a large foramen which communicates with the interior surface of the maxilla. The anterior edge of the maxilla forms the posterior part of the notch with the premaxilla and has a short anterior process that projects into the notch. The dorsal part of the maxilla contacts the lacrimal half way along the dorsal edge of the antorbital fenestra and at the posteroventral angle of the fenestra. The full extent of the contact between the maxilla and jugal is not obvious on the specimen, but most of it lies ventral to the lacrimal so that the maxilla does not extend posteriorly beneath the orbit. At its contact with the jugal the ventrolateral part of the maxilla has a thin lamina which ascends dorsally to overlie part of the jugal, although the jugal overlies the maxilla along most of the contact. The ventral border of the maxilla is straight, lacking the ‘festooning’ commonly found in crocodyliforms. Small neurovascular foramina are present on the lateral surface of the maxilla dorsal to the tooth row; there are slightly fewer foramina than teeth.

The anterior halves of the maxillae form a secondary bony palate, which extends back to the level of the sixth maxillary tooth. From here it continues posteriorly as a narrow palatal shelf. The palatine contacts the maxilla posterior to this narrow shelf. The ventral surface of the secondary palate is covered with many tiny pits in a pattern similar to that seen on the occipital surface of the squamosal. At the midline, the bone rises dorsally to form a longitudinal ridge along the dorsal surface of the secondary palate. Slightly posterior to the secondary bony palate, a ridge arises from the dorsal surface of the palatal shelf and ascends a short distance anterodorsally onto the medial surface of the facial part of the maxilla; possibly soft tissue forming the dorsal roof of the narial passage attached to this ridge. The vomer articulates bluntly with the maxilla at the posterodorsal edge of the secondary bony palate along the midline.

The vertically oriented lacrimal separates the antorbital fenestra and orbit ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Most of the left element is preserved on the rostral fragment except for its posterodorsal part near the contact with the prefrontal. The ventral portion of the lacrimal is vertical and forms the posterior border of the antorbital fenestra and the anterior border of the orbit. The dorsal portion of the bone is horizontal and extends anteriorly dorsal to the antorbital fenestra. It is narrow, as in Sphenosuchus , rather than having a broad ventral lamina extending into the antorbital fossa, as in Pseudhesperosuchus ( Bonaparte, 1972a) and Terrestrisuchus ( Crush, 1984) . The ventral part of the lacrimal is gently concave posteriorly and gently convex anteriorly. It bears a thin vertical ridge on its lateral surface and broadens medially. The lacrimal broadens ventrally at the contact with the maxilla (and possibly jugal), and it may also meet the palatine in this area. The contact between the lacrimal and prefrontal is not preserved. The posterior entrance of the lacrimal canal could not be identified.

The jugal is represented only by the anterior end of the left element lying beneath the orbit. It is relatively narrow compared with that of crocodylians. Its contact with the lacrimal is not evident, but it clearly did not ascend far dorsally as in some basal archosaurs. The medial surface of the anterior end is concave, wrapping around the posterior end of the maxilla.

The squamosal lies at the posterolateral corner of the upper temporal region, extending laterally over the quadrate. It is thin and similar to that of Saltoposuchus ( Sereno & Wild, 1992) and Terrestrisuchus ( Crush, 1984) . Laterally, it bends downward so that this part of the bone is orientated vertically ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). This may be partly owing to the lateral compression of the fossil, but the shape of the occipital portion of the bone suggests that the bend is for the most part a natural feature. The border of the occipital portion of the bone has a smoothly curved edge that follows the bend in the body of the bone, so that, had the body of the bone been essentially horizontal before crushing, the fragmentation of the occiput would have been more severe. The medial part of the squamosal also bends downward abruptly along the lateral edge of the supratemporal fenestra, although a true descending process as seen in primitive archosaurs and dinosaurs is absent. This portion of the bone is relatively short and of an even height throughout.

The contact between the quadrate and squamosal lies along this part of the bone. Anteriorly, lateral to the supratemporal fenestra, this contact is a lap joint, with the squamosal lying medial to the quadrate. Posteriorly, in the area where the quadrate contacts the prootic, the quadrate abuts directly against the ventral surface of the squamosal, although there is a small ventral extension of the squamosal lateral to the quadrate. The dorsal part of the quadrate continues posteriorly beneath the squamosal to contact the anterior surface of its occipital part. There is no indication of a socket within the squamosal for the quadrate, as in Sphenosuchus ( Walker, 1990) and more primitive archosaurs. As in crocodyliforms (with the exception of Eopneumatosuchus ; Crompton & Smith, 1980), the anterior part of the quadrate is not sutured to the squamosal, but merely underlies it. However, a break in the right squamosal reveals that, unlike in crocodyliforms, the quadrate is not sutured to the squamosal posterior to the supratemporal fenestra. The anteroposterior development of the quadrate beneath the squamosal suggests that little, if any, movement was possible along this contact, especially in an anteroposterior direction.

The occipital portion of the squamosal ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ) is extensive, being equal in height to the supraoccipital bone. It descends ventrally along the posterior surface of the paroccipital process to opposite the dorsal border of the foramen magnum. Its ventral edge is straight and horizontal. The squamosal appears to underlie the parietal posteriorly on the occipital surface. The two bones meet along an extensive contact so that the squamosal has no, or a very slight, contact with the supraoccipital. In posterior view, the contact between the squamosal and parietal is oblique, extending ventromedially from the dorsal surface of the skull. The occipital surface of the squamosal is covered with tiny pits.

The lateral surface of the squamosal is broadest posteriorly, its ventral edge being orientated obliquely at an angle of about 45 °. The occipital portion of the squamosal extends ventrally along the lateral edge of the paroccipital process to cover its lateral surface. The lateral edge of the squamosal on the occiput forms a strong ridge that extends posteriorly. It has a rough surface, especially dorsally. The lateral surface of the squamosal is sculptured in a complex pattern. The area along the anteroventral edge is roughened, and a low ridge is developed paralleling this roughness posterodorsally. Together these two features form a groove extending most of the length of the bone ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Anteriorly, this groove extends onto the dorsal surface of the bone as the descending portion of the bone gradually narrows. The ridges and groove terminate posteriorly opposite the level of the occiput where the groove turns downward and reaches the ventral edge of the bone. The groove may have served for the attachment of muscles for an ear flap as in extant crocodylians ( Shute & Bellairs, 1955). A raised area is situated within the groove at its posterior end, as seen on the right side. Posterior to the groove, the lateral surface of the squamosal is roughened in a more regular pattern.

The contact between the parietal and squamosal posterior to the supratemporal fenestra on the dorsal surface of the skull is very short, especially in comparison with crocodyliforms. It is less than one quarter the length of the squamosal, compared to about half the length of the squamosal in crocodylians. The squamosal does not appear to border the anterior temporal foramen (for the passage of a. temporo-orbitalis) as it does in Dibothrosuchus and crocodyliforms. The contact of the squamosal with the postorbital is not preserved.

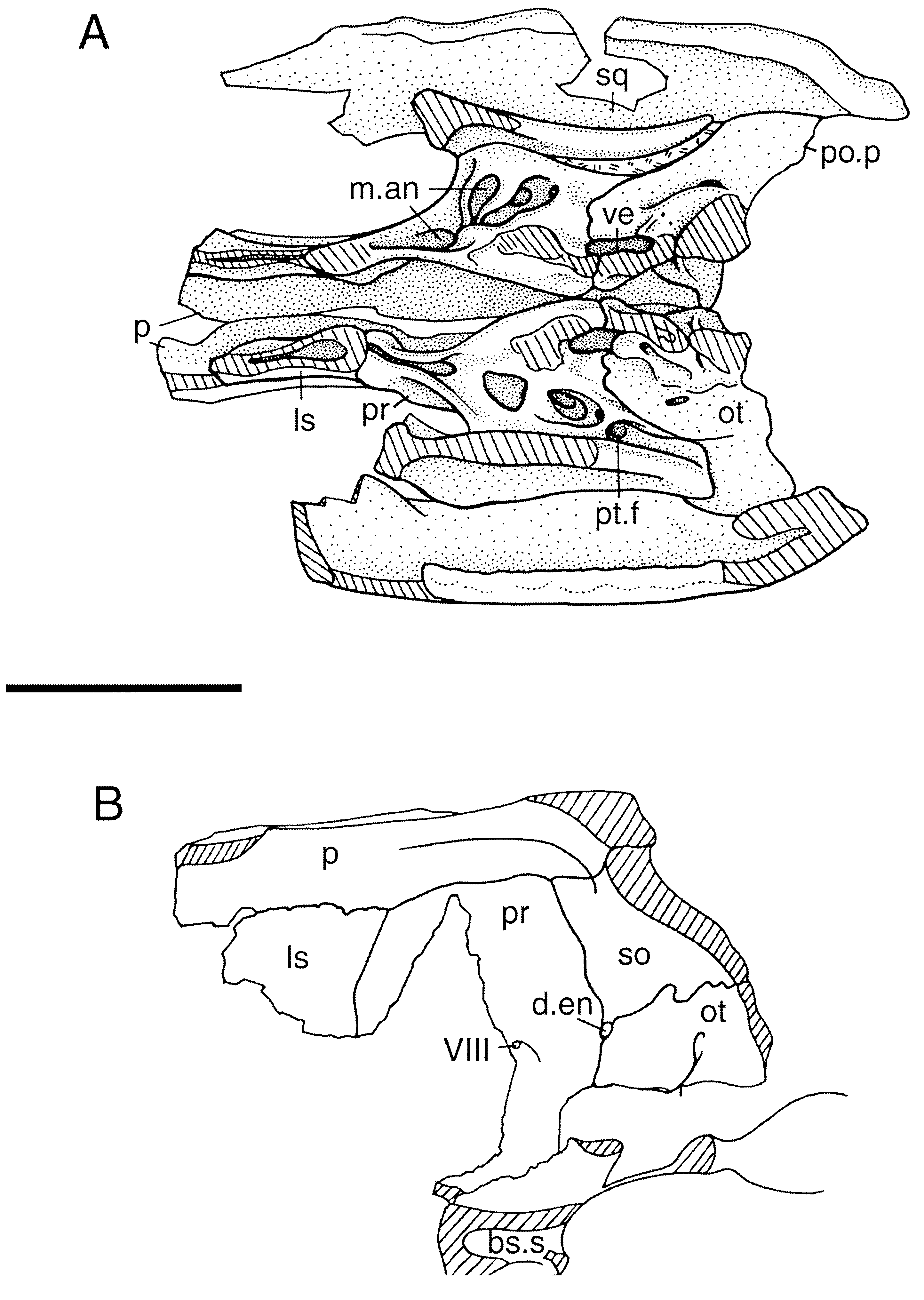

The parietals appear to be fused, but this is difficult to determine with certainty because they have separated along the midline and the contact surface is damaged. Anteriorly, they appear to have separated along an open suture, but posteriorly the break is not directly through the midline and no suture is apparent. It is possible that, as in Litargosuchus , the parietals were fused posteriorly but suturally separated more anteriorly. The anterior end of the bone is missing from the braincase pieces, but a fragment containing the anterior end of the left parietal and the posterior end of the frontal is preserved. In dorsal view, the parietal broadens posteriorly and, to a lesser extent, anteriorly; thus the lateral edge of the bone is concave where it borders the supratemporal fenestra. Anteriorly, near the frontal contact, the lateral edges become parallel. The parietal is similar in length to that of Sphenosuchus , Saltoposuchus , Terrestrisuchus , and Pseudhesperosuchus . A distinct rugose ridge along the lateral edge of the parietal clearly marks the dorsal limit of m. adductor mandibulae within the supratemporal fenestra. These ridges are separated by a broad expanse of bone on the skull roof, in contrast with Sphenosuchus and Dibothrosuchus in which a very narrow sagittal crest is formed along the dorsal midline. The dorsomedial surface is broadly rounded transversely, and the lateral edge of the dorsal surface is turned upward. The parietal extends ventrally from its lateral ridge to meet the endochondral bones of the braincase ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). It contacts the laterosphenoid ventrally along the medial surface of the supratemporal fenestra, and in this area the lateral surface of the parietal is relatively flat. Posterior to the supratemporal fenestra the parietal contacts the prootic. Here its lateral surface is concave, with the ventral edge flaring laterally at the prootic contact. The parietal contacts the supraoccipital at the posterior end of the braincase, where it entirely overlies the supraoccipital dorsally. The extensive occipital portion of the parietal ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ) is wedge-shaped, thinning ventrally. It has broad contacts with the squamosal laterally and the supraoccipital medially on the occiput, and it has only limited (if any) ventral contact with the otoccipital. In dorsal view, the posterior edge of the parietal is concave posteriorly. The area dorsal to the supraoccipital is strongly concave, but flattens out laterally.

The frontals roof the orbits. They are incompletely preserved; the medial parts of both bones are preserved together as an isolated fragment, and the posterior region of the left frontal forms another isolated fragment with the anterior part of the left parietal. The parietal extends anterolaterally along the edge of the supratemporal fenestra to separate it from the frontal. The ridge on the dorsal midline of the parietal continues anteriorly onto the frontals. The ridge becomes broader anteriorly, and its surface is slightly sculptured with narrow grooves. The lateral portion of the frontals is not preserved, but the broken edges are thinner than the medial part of the bones. Thus it is likely that the frontals are similar to those of Sphenosuchus and Hesperosuchus ( Walker, 1970) in having depressions lateral to a midline ridge. The frontals of Kayentasuchus lack the three longitudinal ridges on their dorsal surface that are diagnostic for Dibothrosuchus ( Wu & Chatterjee, 1993) .

The ventral surface of the frontals is poorly preserved, but the cristae cranii bordering the olfactory tracts were well-developed. A single small foramen marks the frontal lateral to the right crista. A fragment underlying the right nasal is probably part of the frontal, so that the frontal extended anteriorly beyond the level of the orbit. The anterolateral and posterolateral edges of the frontals, and thus the contacts with the prefrontal and postorbital, are not preserved.

The postorbitals are no longer attached to the frontal, jugal or squamosal, but isolated fragments are tentatively identified as the body of each bone. These remnants reveal little of the structure of the elements other than the presence of a spherical protuberance on their anterolateral corner.

The right quadrate has some fragments of bone adhering to its anterior edge; these pieces probably represent the quadratojugal. The dorsal part of the anterior margin of the quadrate has no fragments adhering to it (although a substantial amount of matrix was still present in this region prior to preparation), and the quadratojugal may not have extended dorsally to reach the top of the lateral temporal fenestra. Thus this region of the skull appears to resemble the condition in Dibothrosuchus , Hesperosuchus , and Sphenosuchus , as reinterpreted by Clark et al. (2001).

The rod-like vomers unite along the midline and extend between the secondary bony palate formed by the maxillae. The articulation with the maxilla along the posterodorsal edge of the secondary bony palate is somewhat damaged, but there is a matrix-filled area that probably represents this contact. The anterior end of the vomer has a flat ventral surface and appears to fit around a projection of the maxilla at their contact. The central part of each vomer is hemicylindrical so that the vomers together form a cylinder, and there is a short lateral flange on the dorsal edge of each. The posterior part of the vomer has a dorsally projecting ridge on its medial edge that meets its counterpart along the midline. The bones flatten out posteriorly and diverge as they meet the ventral surface of the palatines. It is not clear whether the vomer meets the pterygoid, which is the plesiomorphic condition for Archosauria and is retained in Sphenosuchus ( Walker, 1990) and Dibothrosuchus ( Wu & Chatterjee, 1993) .

The palatines are poorly preserved, but they clearly do not form part of the secondary bony palate. The anterior end of the palatine articulates with the maxilla medially and extends anteriorly to underlie the posterior part of the palatal shelves of the maxilla for a short distance. The palatine forms the anterior border of the suborbital fenestra, as is visible on the impression of the right element associated with the right dentary fragment, but little detail is preserved. Strong ridges of the type found in Sphenosuchus ( Walker, 1990) are apparently absent on the ventral surface of the palatine posterior to the choana.

The pterygoids are poorly preserved. Impressions of the anterior parts of the bones are preserved in association with a fragment of the right dentary. An interpterygoid vacuity does not appear to be present at this end, but this might be due to the postmortem transverse crushing of the skull.

Portions of the ectopterygoids are preserved adhering to the two pieces of the posterior parts of the two mandibular rami. They exhibit few details but do not appear unusual.

There is no evidence of palpebral bones, but the orbital region is poorly preserved.

Only the dorsal portion of either quadrate is preserved. Comparisons with Sphenosuchus and Hesperosuchus indicate that only approximately half the bone is represented. The bone is solid, and the area that bears a depression in Saltoposuchus and other related taxa is not preserved. The dorsal part of the quadrate is relatively long anteroposteriorly and extends beneath the squamosal from the occiput to a point opposite the trigeminal foramen. It contacts the anterior surface of the occiput posteriorly and is slightly expanded at that contact ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). It mainly contacts the squamosal posteriorly, but it also contacts the lateral surface of the paroccipital process.

Medially, the quadrate broadly contacts the prootic ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ), and together the two bones form the posterior surface of the supratemporal fenestra. The medial surface of the quadrate bears a prominent ridge that begins dorsally at the anterior end of the prootic contact and extends ventrally to the broken edge. The pterygoid ramus was not preserved, but it probably extended anteriorly from this ridge further ventrally. The dorsal end of the ridge lies slightly anterior to the middle of the quadrate, and ventrally it moves posteriorly until at the broken ventral edge of the right element it is situated midway between the anterior and posterior edges. The medial surface of the quadrate anterior to this ridge likely served as the origin of mm. adductor mandibulae externus profundus and adductor mandibulae posterior ( Busbey, 1989). The preserved portion of the quadrate extends in a parasagittal plane, so the ventral part of the bone must have twisted in order to form the transversely orientated condyles.

The supraoccipital and epiotic bones are indistinguishably fused together and are referred to as the supraoccipital. The supraoccipital forms the middorsal portion of the occiput, the dorsal part of the otic capsule, and the posterodorsal roof of the braincase beneath the parietal ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ). It is slightly higher than wide on the occiput, so that, allowing for the lateral compression of the specimen, the two dimensions were probably more or less equal. The supraoccipital narrows above and below the level at which the squamosal, parietal, and otoccipital come together. The ventral narrowing is abrupt, but the dorsal narrowing is more gradual, so that the dorsal part of the bone is about twice as high as the ventral. The supraoccipital is overlain dorsally by the parietal and contacts the otoccipital ventrolaterally. The occipital surface of the bone is pitted like that of the squamosal, but the surface is otherwise smooth.

On the internal surface of the braincase, a thick vertical ridge extends along the ventral midline surface of the supraoccipital. The supraoccipital forms the dorsal third of the otic capsule, contacting the otoccipital and prootic. A well-developed subarcuate fossa is present in the bone posterior to the otic capsule. The superior tympanic recess does not extend into the supraoccipital; thus, the horizontal lamina of bone between the posterior ends of the otic capsules on crocodyliform supraoccipitals is absent. The supraoccipital may barely have entered into the dorsal margin of the foramen magnum.

The exoccipital and opisthotic appear to be indistinguishably fused together and are here referred to as the otoccipital. The otoccipital forms the ventrolateral portion of the occiput ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ) and the posterior part of the otic region ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). The paroccipital processes are poorly documented, and only their dorsal part is preserved on each of the two braincase pieces. Part of the ventral portion of the right paroccipital process is present on a separate piece attached to the right prootic. A bend in this piece suggests the possible presence of a suture between the paroccipital part of the opisthotic laterally and the exoccipital medially, but no such suture is discernable on the dorsal part of the bone. A cast of the right quadrate on the matrix around this piece allows it to be fitted with the actual quadrate on the braincase piece. This indicates that the paroccipital process was relatively broad vertically. The dorsal part of the otoccipital is preserved on both braincase pieces, and the ventral part of the otic region of the otoccipital is preserved in articulation with the right prootic ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). The structure of the otic region is nearly identical to that described for Sphenosuchus by Walker (1990). The otoccipital portion of the cochlear prominence is a thick, arched structure that broadly meets the prootic below the otic capsule. It is broken dorsally at the base of the crista interfenestralis on the prootic piece, and the braincase piece preserves the posterodorsal base of the crista. The anterior wall of the opening for the foramen perilymphaticum and fenestra pseudorotunda is well preserved on the prootic piece, but the posterior wall is not preserved. The subcapsular process is also missing.

The prootic forms the lateral wall of the braincase between the otoccipital and laterosphenoid ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). Its dorsal portion is preserved on both braincase pieces, and the posteroventral part of the right prootic is preserved in articulation with the otoccipital and basisphenoid. Ventrally, the prootic portion of the cochlear prominence is much thinner than that of the otoccipital. Posterior to the cochlear prominence, the lateral surface of the prootic has several depressions similar to those in Sphenosuchus that Walker (1990) interpreted as pneumatic spaces. Ventrally, the prootic articulates with the basisphenoid. The anterior part of this contact suggests that, as in Sphenosuchus , the basisphenoid rises anteriorly and the ventral edge of the prootic rises with it. A groove extends on the medial surface of the capsular portion of the (right) prootic, and at its anterodorsal end lies a foramen for one branch of n. vestibulo-cochlearis (VIII). The prootic continues forward from the otic region to contact the laterosphenoid. This portion of the prootic is longer than that of crocodylians but is similar in size to that of basal crocodyliforms. Its dorsal edge contacts the parietal along a straight, horizontal suture. The lateral surface of the prootic below its contact with the parietal forms the medial part of a shelf in the posterior part of the supratemporal fossa. The medial surface of the prootic on this shelf forms the medial surface of a long groove leading into the anterior temporal foramen (for the passage of a. temporo-orbitalis). Laterally, the prootic forms a broad contact with the quadrate. The prootic is hollowed out and supported only by a series of thin transverse struts between this contact and the otic capsule; these spaces appear to be parts of the mastoid antrum. As best seen on the right side, there are three spaces separated by two struts. The spaces extend dorsally well into the dorsal part of the bone. The foramen for the passage of n. trigeminus (V) is not preserved.

The laterosphenoids are poorly preserved. As discernable on the right side, the laterosphenoid is hollow, but it probably was not connected with the pneumatic cavities of the middle ear. It is thick at its posterior contact with the prootic but not at its dorsal contact with the parietal.

A fragment of the right side of the basisphenoid is preserved in articulation with the prootic ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). A large space lies within the bone immediately ventral to the prootic; in comparison with Sphenosuchus ( Walker, 1990) , it is situated within the body of the bone posterior to the postcarotid recess.

The basioccipital is not preserved.

MANDIBLE

The dentary forms the anterior portion of the mandibular ramus ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). It takes part in a relatively long symphysis, extending from the anterior end of the ramus back to the level of the fourth maxillary tooth. The dentary narrows gradually anteriorly and is slender at its tip. It is bent at the posterior end of the symphysis, so that its dorsal edge is concave. The left dentary is preserved with its posterior part projecting upward into the jugal and its symphyseal region turned upward into the premaxillae, but this was probably not the original orientation of the lower jaw. The posterior contacts of the dentary may be present on a block preserving the posterior part of the left mandibular ramus, but they are not obvious.

The splenial is a broad sheet of bone covering the medial surface of the dentary. It barely enters into the long symphysis anteriorly. Anteriorly, the dorsal part of the splenial ends short of the symphysis and only the ventral part continues forward. Thus a small, elongate fenestra is formed on the medial surface of the mandibular ramus opening into the Meckelian groove on the dentary.

The postdentary bones are preserved on two fragmentary pieces, one from each side. The large external mandibular fenestra is best preserved on the piece from the left side. It has sharp anterior and posterior ends, but its upper and lower margins are smoothly curved. However, few details are preserved on these pieces, and the articular and prearticular are apparently not preserved.

DENTITION

The premaxilla holds four teeth ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). The first tooth is smaller than the others, but all are similar in shape. The crowns are nearly conical but are slightly compressed labiolingually and have distinct but nonserrated anterior and posterior cutting edges. The second and third teeth are slightly constricted at the base of the crown. The third tooth on the right side was in the process of replacement; replacement was typically crocodylian, with the replacement tooth emerging lingual to its predecessor.

There are positions for at least 12 and probably no more than 13 maxillary teeth were present. The tooth crowns increase in diameter back to the sixth tooth and decrease in diameter posterior to the ninth. The tooth row terminates posteriorly at the level of the posterior margin of the antorbital fenestra. The individual alveoli are separated from each other by septa (e.g. between the fifth and sixth alveolus on the left side), and interdental plates are absent on the lingual surface of the maxilla. The tooth crowns are nearly conical, slightly compressed labiolingually,and have distinct anterior and posterior cutting edges. They are thus similar to those of Sphenosuchus , which Walker (1970, 1990) described as ‘lanceolate’. The cutting edges lack serrations, and there are longitudinal crenulations on the lingual and labial surfaces that are coarser near the tip. The enamel on all teeth is very thin. Broken surfaces on isolated pieces of the right maxilla reveal that the teeth are separated from the bone by matrix, suggesting that they were held in their bony alveoli by periodontal ligaments in the typical archosaurian manner.

The dentary holds at least but probably no more than 13 teeth. The first centimetre of its anterior end is devoid of teeth, representing the length of approximately three or four alveoli. Posterior to this edentulous segment, the alveoli are similar in size, and, unlike in other basal crocodylomorphs, there is no trace of a large caniniform tooth opposite the notch between the premaxilla and maxilla. The alveoli increase slightly in size posteriorly to about the fifth tooth position. The teeth are identical to those of the maxilla; they are nearly conical and constricted at the base. The alveoli are separated by septa, as most clearly seen on the right dentary.

ILIUM AND FEMUR

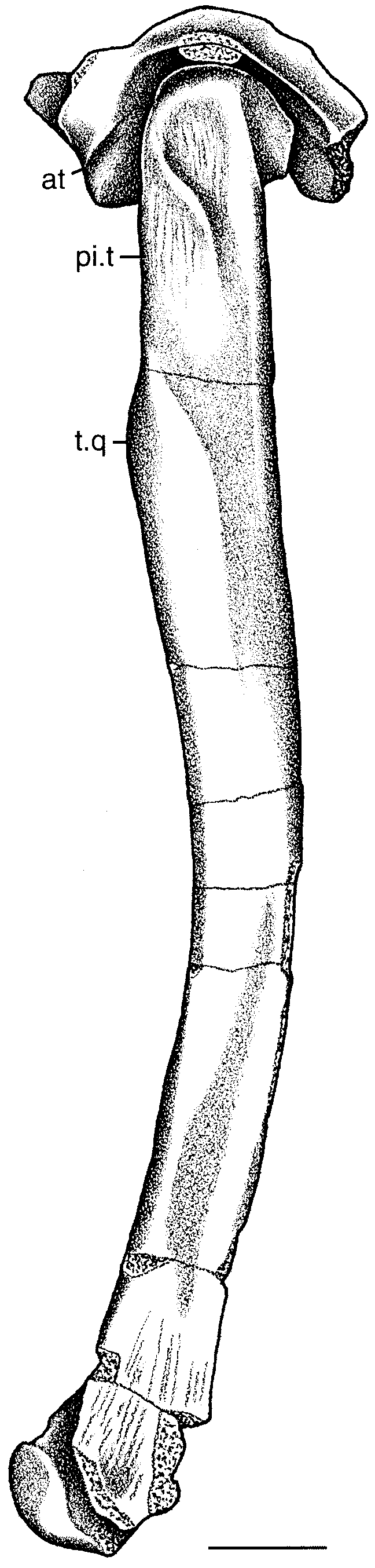

The right ilium and femur are preserved in articulation ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ); fragments of the left ilium and femur are also preserved but have not yet been prepared. The right ilium is represented only by the portion of the bone surrounding the acetabulum, and the iliac blade as well as its anterior and posterior processes are not preserved. The acetabulum is deeply concave and overhung by a broad supra-acetabular crest. The crest is broadest anteriorly and does not extend to the posterior edge of the acetabulum. The medial wall of the acetabulum is perforated, as indicated by a concave notch in the ventral edge of the ilium. This notch is somewhat broader and deeper than that on the ilium of crocodylians, but it is not as large as in dinosaurs. Unlike the condition in Terrestrisuchus ( Crush, 1984) , the posterior edge of the iliac crest projects posteriorly without forming a posteriorly facing notch with the acetabular portion of the bone. The posteroventral surface for the contact with the ischium is broad and becomes much thicker laterally. Immediately above the lateral edge of the ischial contact lies a thin ridge forming a groove along its posteroventral edge. This is more or less in the same position as the antitrochanter of birds and theropod dinosaurs, but differs from the latter in shape.

Fragments of two sacral vertebrae are preserved articulating with the medial surface of the ilium. There is no indication that additional vertebrae were involved in the formation of the sacrum. The rib of the second sacral vertebra is broader than that of the first (although the latter is incomplete). It contacts the ilium from a point behind the middle of the acetabulum posteriorly and extends well onto the broken posterior process. The rib of the first sacral vertebra articulates in a longitudinal groove medial to the anterior process.

The proximal end of the femur has a well-developed inturned head. The articular surface of the head extends over its convex, ball-shaped medial surface and laterally across its posterodorsal surface. The articular surface does not extend onto the flat anterior surface of the head. The head is orientated at a right angle to the shaft, so that the hindlimb appears to have been fully erect. The ‘lesser trochanter’ ( Walker, 1970) is well developed on the anterior part of the lateral surface of the shaft. It is relatively long and is orientated along the long axis of the bone, descending from the lateral surface of the femoral head. A second well-developed trochanter on the posterior edge of the lateral surface opposite the lesser trochanter ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ) may correspond to a similar feature in Hallopus that Walker (1970) termed the ‘pseudointernal trochanter’ for the insertion of m. puboischiofemoralis externus ( Romer, 1923; Hutchinson, 2001), but the trochanter on the femur of Kayentasuchus is situated further from the posterior edge of the bone. This structure parallels the lesser trochanter, but does not extend as far dorsally and its ventral end is more robust. Together the two trochanters define a distinct longitudinal groove on the lateral surface of the femur. The fourth trochanter is situated approximately one-fourth of the distance down the shaft on its posteromedial edge. It is not as pronounced as the other two trochanters.

The shaft of the femur is remarkably slender and similar to that of Terrestrisuchus ( Crush, 1984) . Although it has been distorted by lateral compression, it appears to have been more cylindrical distally and laterally compressed at its dorsal end. The proximal quarter of the shaft is nearly straight, but its distal three-quarters are distinctly curved so that its posterior edge is broadly concave. Thus its shape is not truly sigmoidal as in crocodyliform femora because its anterior edge lacks a concavity in its dorsal part. The distal condyles of the femur are poorly preserved, although the medial condyle is fairly complete. It is laterally compressed, but this may be an artifact of preservation.

OSTEODERMS AND VERTEBRAE

Several sections of poorly preserved dorsal osteoderms are preserved with the specimen. Most of the bone has shattered, but the impressions are preserved in ironstone. A series of three nearly complete sections of body armour is preserved as impressions and surrounding vertebrae. It is unclear what part of the body these are derived from, but, based on the width of the dorsal osteoderms and the compactness of the vertebrae, they are probably from the trunk rather than the caudal or cervical region.

A pair of longitudinal rows of broad dorsal osteoderms is preserved. The best preserved plates, from the right side, are rectangular, about twice as wide as long, and on the lateral part of the anterior edge is an impression of an anterior process similar to that found on many crocodyliform osteoderms. The dorsal osteoderms on the left side are strongly bent, unlike those on the right which are more gently downturned; the actual condition was presumably between these two extremes, which are probably the result of postmortem distortion. In any case, the lateral portion of each osteoderm is deflected to some extent.

The ventral osteoderms are subquadrangular and apparently not imbricated. They are much smaller than the dorsal osteoderms, about half the anteroposterior length and one quarter of the transverse width. Two longitudinal rows are well preserved, and there appear to be additional rows folded under the dorsal osteoderms. A separately preserved ventral osteoderm exhibits a finely sculptured surface of pits and ridges.

Few vertebrae are preserved, and none is as yet completely prepared. Those examined all belong to the trunk region. They are amphicoelous and relatively stout.

| UCMP |

University of California Museum of Paleontology |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.