Loxodonta cyclotis (Matschie, 1900)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6511086 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6511102 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/29264D66-FFCA-981E-F665-22DEF79CFDC6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Loxodonta cyclotis |

| status |

|

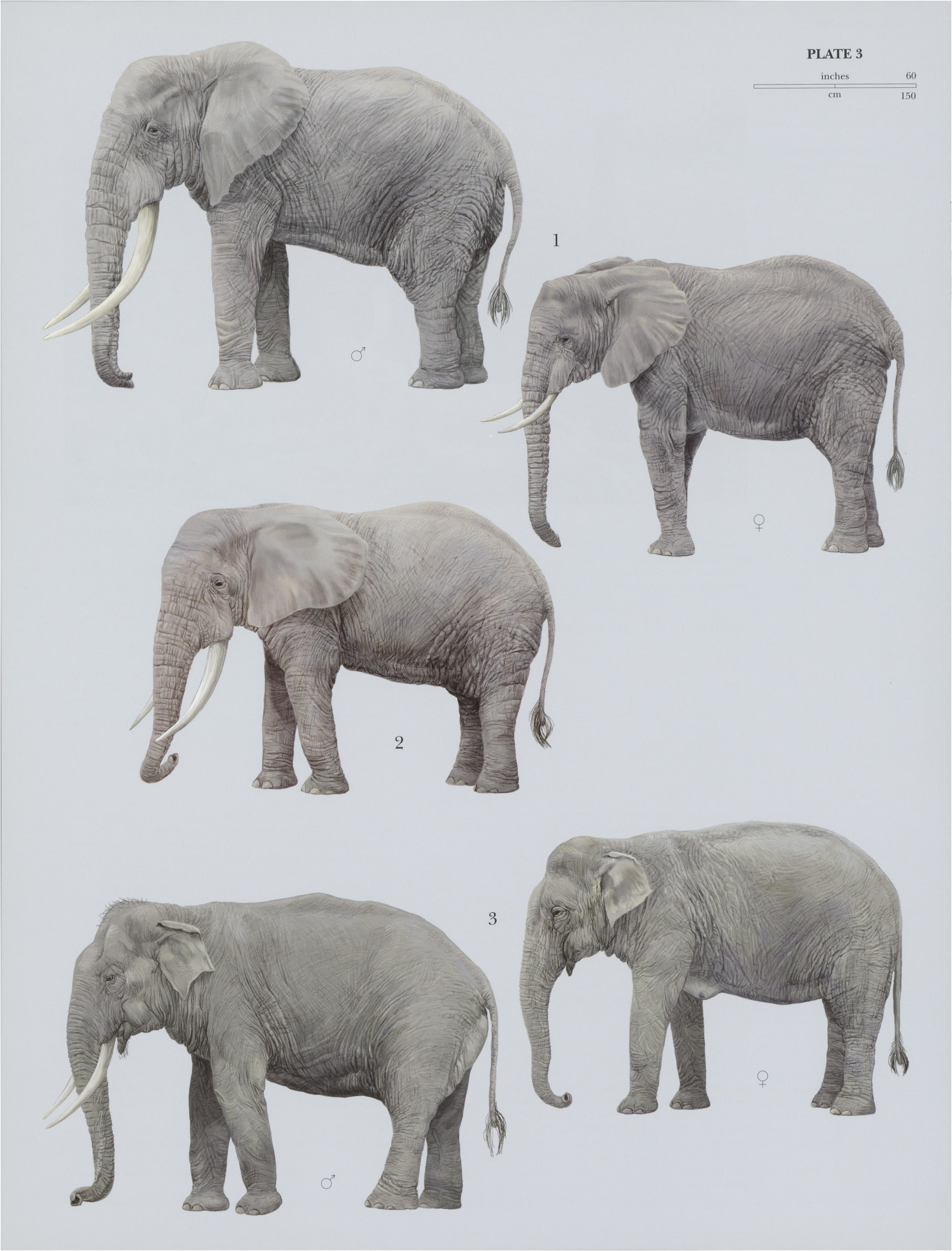

2. View Plato 3

African Forest Elephant

Loxodonta cyclotis View in CoL

French: Eléphant de forét / German: Afrikanischer Waldelefant / Spanish: Elefante de bosque

Taxonomy. Elephas cyclotis Matschie, 1900 , Yaunde, S Cameroon.

African Forest Elephants (L. cyclotis) were treated as a subspecies of African Savanna Elephants ( L. africana ) until recent genetic work provided evidence of differentiation that was interpreted as meriting distinction as two species. Debate on the species vs. subspecies classification continues, in part because the distinction fails the biological species concept (hybrids between the two produce viable offspring). No subspecies of L. cyclotis are delineated, though recent work indicates the genetic distinction between West and Central African Forest Elephants may merit consideration at a subspecies or even species level. Currently, West African elephants inhabiting forest ecosystems are typically treated as African Savanna Elephants. Morphological differentiation across African Forest Elephant populations is not well described. Where accounts have been made, differentiation appearsto relate to the degree of mixing with African Savanna Elephants. Monotypic.

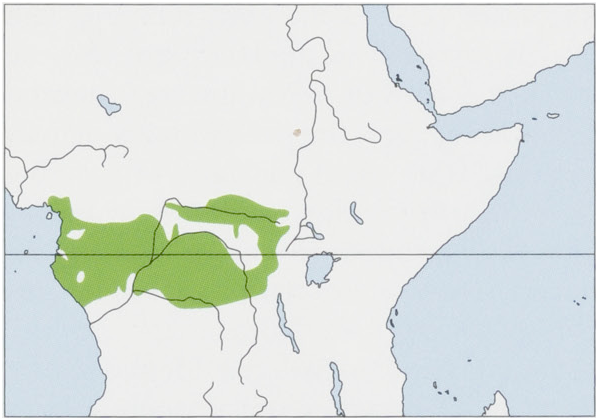

Distribution. Congo Basin in C Africa (S Cameroon, S Central African Republic, DR Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Republic of the Congo). Distribution of this recently recognized speciesis still not well known and the range map is only speculative. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body (including trunk) 600-750 cm, tail 100-150 cm, shoulder height 160-286 cm (males), 160-240 cm (females); weight 2700-6000 kg. African Forest Elephants are typically smaller than their savanna relatives and on the smaller side of these measurements, with shoulder heights up to a meter less than averages in African Savanna Elephants. Other differences include more rounded features, smoother skin, less body hair, and generally straighter tusks. Despite these differences, other physical characteristics largely mirror those of African Savanna Elephants, and morphological similarity is thought to vary with the degree of hybridization.

Habitat. Generally restricted to the Central African tropical forest basin, preferred habitats tend to be areas containing secondary growth. The highest densities of elephants recorded (in either forest or savanna regions) were in the finger forest of Central Africa where savanna and tropical forest interface. As such, a mosaic of forest grasslands can be considered preferred habitat. Within forests, bais containing mineral deposits are hot spots of activity and a critical component of an individual’s range. It is likely that bai mineral deposits are a primary limiting resource in forest ecosystems. Currently, as with other elephant species, distribution is primarily a function of human density and hunting pressure. Large areas of protected forest are now devoid of elephants due to overharvesting.

Food and Feeding. Diets are almost entirely browse-based, except on the forest fringe where some populations may rely on grasses in addition to browse. These populations are typically African Savanna and African Forest Elephant hybrids such as those found in Garamba National Park in the DR Congo. Like African Savanna Elephants, they utilize an incredible array of plants and may focus on different portions of the same species at different times of the growing season. It is speculated fruit is a critical part of African Forest Elephant diet, particularly in old growth regions where much of the biomass is in the canopy. African Forest Elephants are keystone seed dispersers in these habitats. Preference for disturbed secondary growth habitats such as logged forest tracts has been found, probably due to lower canopy height and decreased plant toxicity in the secondary growth.

Breeding. Physiological reproductive parameters mirror those of African Savanna Elephants, with a 22month gestation followed by an extensive period of postpartum calf rearing that precludes reproduction. The average intercalf interval appears to be 4-5 years, though detailed data are not available. Seasonality in breeding may relate to plant phenology as in savanna systems, or mineral access. In one population, it is speculated females ovulate in the dry season, when underground mineral resources, which are inundated during the wet season, are accessible. Males enter the reproductively active state of musth. In contrast to African Savanna Elephants, which appear to search widely for mates, dominant musth bulls can defend mineral deposits in bais to access mates. It is likely that less competitive African Forest Elephant males, like African Savanna Elephant males, search widely for mates.

Activity patterns. Circadian cycles demonstrate activity around 20 hours/day, with sleep occurring in two bouts, one during midday and a longer sleep cycle during the late night. Daily activity is dominated by foraging. Movements between feeding stations may be more common in forests where elephants are targeting point resources more frequently (e.g. fruiting trees), whereas in savanna systems elephants often move while feeding. Water resources are prevalent in Central African forests and do not appear to drive activity or movements.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home range sizes can vary substantially within the same populations, but average around 500 km?* across multiple sites. Substantial differences between males and females are not obvious, with both males and females demonstrating small and large ranges relative to the mean. Movements appear to relate strongly to resource distribution and human activity, with increasing evidence of range constriction because of road development in the Congo Basin. Daily movements tend to be smaller than those of African Savanna Elephants in more xeric habitats, likely at the scale of a few kilometers per day. Information on female social relations is limited. Initial research suggests the fission-fusion model of African Savanna Elephant social organization is prevalent in forest systems, though core groups are much smaller, mostlikely as a function of resource constraints. Hierarchical social relations appear likely. Males appear to be largely solitary, although specific individuals likely maintain weak bonds.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Considered a subspecies by IUCN and currently classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Large scale declines in African Forest Elephants have occurred since the early 1970s, probably in the order of 50-80%. The current population inhabiting the greater Central African region is 50,000 -136,000, though savanna and hybrid morphs likely represent over a quarter of these. Most of these declines are driven by illegal ivory harvesting, as the dense ivory of these elephants is highly valued internationally (African Savanna Elephant ivory is less valuable). Currently range reduction resulting from forest exploitation is also a major threat to the species in many locations. Recently, human-elephant conflicts around agriculture have emerged, though this is still a relatively minorissue in forest ecosystems where agriculture is not as pervasive.

Bibliography. Barnes & Kapela (1991), Blake & Hedges (2004), Blake & Inkamba-Nkulu (2004), Blake, Deem et al. (2008), Blake, Strindberg et al. (2007), Blanc et al. (2007), Fishlock et al. (2008), Laws (1970), Laws et al. (1975), Moss (1988), Roca et al. (2001), Turkalo & Fay (1996).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Loxodonta cyclotis

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Elephas cyclotis

| Matschie 1900 |