Ateles geoffroyi, Kuhl, 1820

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5727205 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5727280 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/313A8814-2A1D-F338-FF80-FE73622DFAB5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Ateles geoffroyi |

| status |

|

13 View On .

Central American Spider Monkey

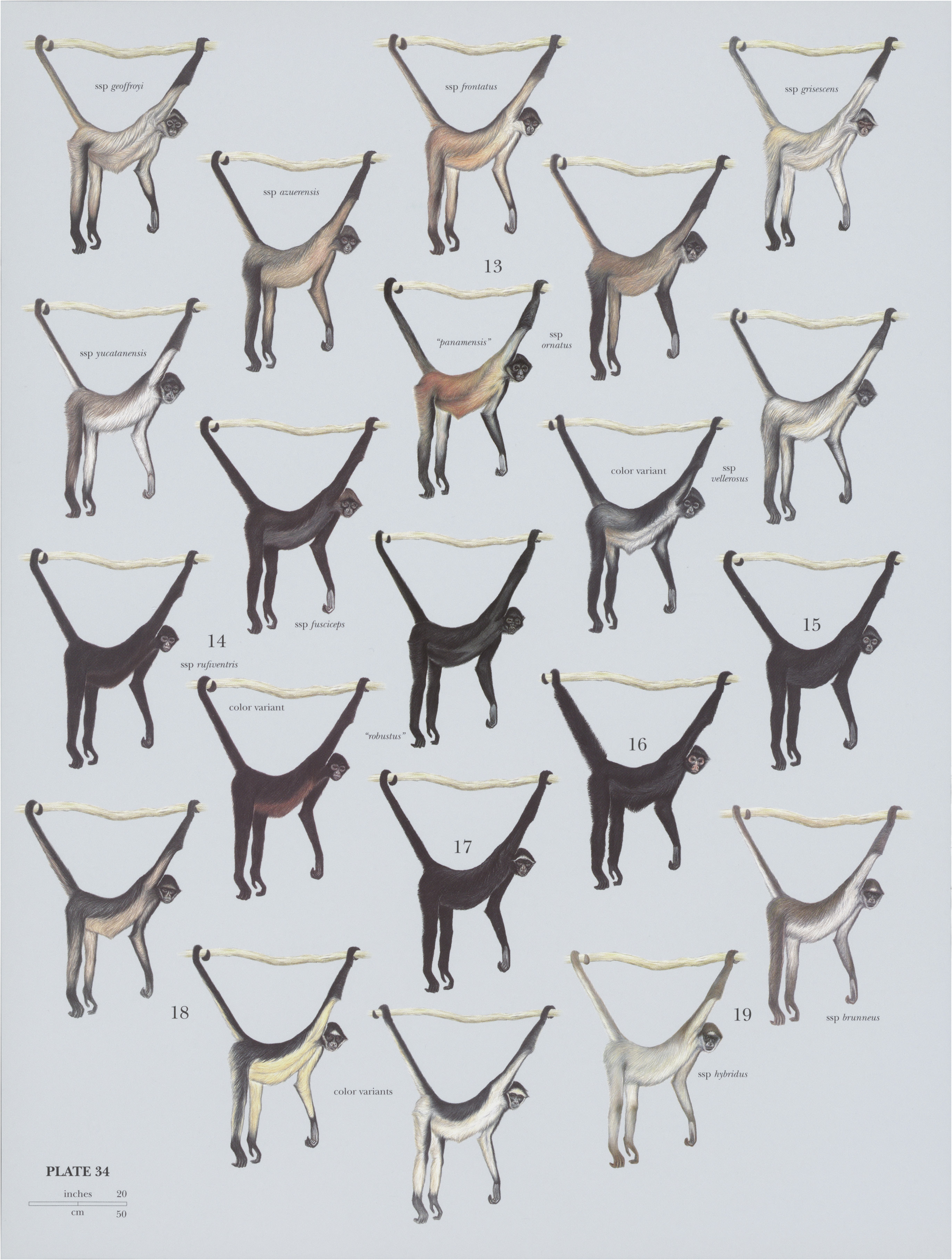

French: Atele de Geoffroy / German: Geoffroy-Klammeraffe / Spanish: Mono arana de América Central Other common names: Black-handed Spider Monkey, Geoffroy's Spider Monkey; Azuero Spider Monkey (azuerensis), Black-browed Spider Monkey (frontatus), Geoffroy’s Spider Monkey ( geoffroyi ), Hooded Spider Monkey (grisescens), Mexican Spider Monkey (vellerosus), Ornate Spider Monkey (ornatus), Yucatan Spider Monkey (yucatanensis)

Taxonomy. Ateles geoffroyi Kuhl, 1820 View in CoL ,

type locality unknown. Restricted by R. Kellogg and E. Goldman in 1944 to San Juan del Norte (= Greytown), Nicaragua .

Ateles geoffroy: 1s highly variable, both individually and geographically, and its taxonomy may still require revision. Seven subspecies are typically recognized: geoffro, azuerensis, Jfrontatus, grisescens, ornatus, vellerosus, and yucatanensis. The form grisescens , however, is of doubtful validity, having never been observed in the wild and being the subject of a single rather poor account regarding a captive specimen. P. H. Napier in her 1976 catalogue of the primate collection in the British Museum (Natural History) argued that the form panamensis is ajunior synonym of ornatus. There is a hybrid zone between the subspecies ornatus and A. fusciceps in Panama. Seven subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution. A. g. geoffroyi Kuhl, 1820 — S & SE Nicaragua (coastal region around San Juan del Norte or Martina Bay, probably ranging across the lowlands to the vicinity of Lake Managua and Lake Nicaragua on the Pacific coast); possibly in N Costa Rica. A. g. azuerensis Bole, 1937 — SC Panama, known only from the forested mountains of the W side of the Azuero Peninsula (Veraguas Province) in the vicinity of Ponuga, where it appears to be isolated; it may also occur to the W along the Pacific coastto the Burica Peninsula, near the Panamanian and Costa Rican border. A. g. frontatus Gray, 1842 — N & W Nicaragua and NW Costa Rica. A. g. grisescens Gray, 1866 — S Panama along the Pacific coast in the valley of the Rio Tuyra and SE through the Serrania del Sapo of extreme SE Panama into the Cordillera de Baudo of NW Colombia. A. g. ornatus Gray, 1871 — C & E Costa Rica, and Panama (from Chiriqui Province to the Serrania de San Blas E of the Canal Zone). A. g. vellerosus Gray, 1866 — E & SE Mexico (E San Luis Potosi, Veracruz, Tabasco, E Oaxaca, and Chiapas states), Guatemala (including the highlands), El Salvador, and Honduras (along the N coastto the lowlands of La Mosquitia in Gracias a Dios Department). A. g. yucatanensis Kellogg & Goldman, 1944 — SE Mexico (forests of the Yucatan Peninsula), NE Guatemala, and adjoining parts of Belize; intergrading in S Mexico (Campeche State) and Guatemala with vellerosus. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—-body 39-63 cm (males) and 31-45 cm (females), tail 70- 86 cm (males) and 64-75 cm (females); weight 7-4-9 kg (males) and 6-9-4 kg (females). The Central American Spider Monkey is extraordinarily variable in its coloration, from yellowish through reddish to blackish-brown on the back and flanks, although there is usually black on the head and limbs and white on the muzzle or around the eyes. Forward-directed hairs from the nape form a sort of cowl that ends in a triangular crest above the brows, and cheek hairs stand out prominently. Roughly from north to south through their distributions, the subspecies appear as follows. Dorsal surfaces of the “Mexican Spider Monkey” (A. g. vellerosus) ranges from black to dark brown, exceptfor a lighter band across the lumbar region, and contrasts strongly with its lighter abdomen and inner limbs. Exposed,flesh-colored skin is often present around the eyes. The “ Yucatan Spider Monkey” (A. g. yucatanensis) is a relatively small, slender subspecies. Its fur is brownish-black on the head, neck, and shoulders, becoming lighter brown on the lower back and hips and contrasting with its silvery-white underside, inner limbs, and sideburns. “Geoffroy’s Spider Monkey” (A. g. geoffroyi ) is silvery to brownish-gray on the back, upper arms, and thighs. A variable amount of black exists on elbows, knees, upper arms, and lower legs, while hands and feet are always black. Its chest coloration is similar to the back, but the lower abdomen may be somewhat golden. The top of its head is dark, sometimes black, with mixed light and dark hairs directed forward, often forming a distinct light band over the forehead. Its face is black, and flesh-colored “spectacles” around the eyes are common. Lighter side whiskers are often present. The tail is bicolored. The “Black-browed Spider Monkey” (A. g. frontatus) is similar in color pattern to the nominate subspecies, although somewhat darker. The “Ornate Spider Monkey” (A. g. ornatus) is a uniformly darker brown than either Geoffroy’s Spider Monkey or the Black-browed Spider Monkey. Its back is golden brown and the face, top of the head, forearms all around, outersides of legs, hands, and feet are black. Its underside does not contrast strongly with the dorsal coat color. The back of the “Azuero Spider Monkey” (A. g. azuerensis) is grayish-brown and somewhat darker than the underside. As in the Ornate Spider Monkey, outer surfaces of its limbs are black, but the top of its head and neck are either black or brownishblack.

Habitat. Primary and secondary lowland rainforest; evergreen, semi-deciduous and cloud forest; and mangrove swamp. The Central American Spider Monkey will also use deciduousforest (Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica).

Food and Feeding. In a nine-month study of the diet of the Yucatan Spider Monkey by J. Cant in Tikal National Park in Petén, Guatemala, 57% of their time was spent feeding on fruit, 14-1% leaves, 10-5% seeds (almost entirely unripe seeds of the breadnut or Maya nut tree, Brosimum alicastrum, Moraceae ), 4-9% unidentified reproductive parts of Brosimum (female flowers, very young fruit, and perhaps male flowers), 2% caterpillars (infested young leaves of Brosimum ), and 1-4% buds (11-1% other items). Depending on the month, fruit comprised up to 84% of the diet and Brosimum seeds 57%. Ninety-seven percent of the leaves eaten were young, and 61% of young leaves and 68% of mature leaves were from Brosimum . Caterpillars were believed to be the only source of animal protein, except for insects ingested incidentally with leaves and fruits such as figs. Brosimum was very important; 56% of the diet was made up ofits fruits, seeds, leaves, and petioles. In upland forests of Tikal, species of Brosimum are very abundant: 11% ofall trees and 21% of the basal area. Other species ofsignificance providing fruits were Spondias mombin (Anacardiacaeae), Dendropanax arboreus ( Araliaceae ), Manilkara achras ( Sapotaceae ), a species of Ficus (Moraceae) , and Cupania prisca ( Sapindaceae ). A study of the Black-browed Spider Monkey by C. Chapman in the deciduous forest of Santa Rosa National Park indicated a diet of 77-8% fruit, 9-8% flowers, 7-:3% young leaves, 2:6% buds, 1-3% insects, and 1-2% mature leaves. Figs made up 29-2% of the diet, and the sweetjuicy fruits of Muntingia calabura ( Muntingiaceae ) 16-1%. Leaves, rather than fruits, made up 70-80% of the diet in the early dry season (January-February). Overall, fruit comprised 14-100% ofthe diet, depending on the month. Fruit was also the major componentof the diet of the Ornate Spider Monkey studied by C. Campbell on Barro Colorado Island, Panama: fruit 81-7% (monthly range 69-91%), leaves 16-7% (6-32%), flowers 1% (0-9%), and insects 0-6% (0-2%).

Breeding. The ovarian cycle of the Central American Spider Monkey is 22-7 days, and menstrual bleeding, not always visible, lasts for 2-4 days. Males evidently show investigative behaviors by sniffing places where a female has been sitting, sniffing her urine, and holding and sniffing her elongated clitoris. These behaviors probably allow a male to assess the reproductive condition of a female. Pairs are more likely to mate when a female is cycling, but they also mate when she is not. Males are aggressive toward females, and mating may often occur by coercion. There is no specific behavior on the part of the female that indicates receptivity. Gestation is 226-232 days. Sex ratio at birth of Black-browed Spider Monkeys at Santa Rosa National Park is 1:1. High numbers of infants have been recorded in the dry season (December—-May) in Santa Rosa. On Barro Colorado Island, most births occur in May-December, with conceptions when fruit is abundant or increasing in availability in December—May. Infants are entirely black, and their coat color lightens appreciably during their first five months. Infants are weaned at 24-26 months old, or more. Juveniles continue to associate with their mothers even when a new infant is born and only begin to move around independently when they are c.3 years old. Females are sexually mature at c.6-5 years old, and they first give birth at c.7 years old. Interbirth intervals were 34-7 months at Santa Rosa and 32 months on Barro Colorado. Individuals maylive up to 27 years.

Activity patterns. A general activity budget of Black-browed Spider Monkeys at Santa Rosa National Park over three years was feeding 33-5%, traveling 32-6%, resting 24-6%, and engaging in social and other behaviors 9-8%.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of Central American Spider Monkeys are 16-24 individuals. Mean daily movement on Barro Colorado Island was 1203 m (range 460-2400 m); daily movements were greater when fruit was abundant in the early and middle wet season. In another study on Barro Colorado, the home range of a group of 20-24 Ornate Spider Monkeys was 963 ha. Their daily movements averaged 2055 m (maximum 4500 m). At Santa Rosa, the home range of a group of 42 Black-browed Spider Monkeys was 42 ha, and their daily movement averaged 1297 m. Female Central American Spider Monkeys disperse from their natal group, but males are generally philopatric. Males are dominant to females. Adult males are more aggressive, show more territorial behavior, and are more socially cohesive than females. Males patrol home range borders, generally in slightly larger subgroups than is typical when they are in other parts of their home range. Adult females are more vocal, more submissive, less social, and more dispersed than adult males. Females tend to travel alone with their infants and juveniles in groups of 3—4 individuals. Adult males travel together but form consortships with females when they are receptive. Densities of 24-5-45 ind/km? were estimated for the Yucatan Spider Monkey in seasonal dry forests of Tikal and they can be as high as 89-5 ind/km? in undisturbed moist forests, such as those at Punta Laguna, Quintana Roo State, Mexico.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I (subspecies frontatus and panamensis, the latter considered here a synonym of ornatus) and CITES Appendix II (other subspecies). Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Subspecies geoffroyi , azuerensis, and vellerosus are classified as Critically Endangered, ornatus and yucatanensis as Endangered, Jfrontatus as Vulnerable, and grisescens as Data Deficient on The IUCN Red List. The Central American Spider Monkey is threatened mainly by habitat loss and fragmentation, with several subspecies having been severely affected. Nevertheless, several large areas of relatively continuous habitat occur in Selva Maya ( Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize), the Atlantic zone of Nicaragua and Honduras, and along the Atlantic coast and the Darien in Panama. It is also affected by pet trafficking and hunting for meat in some areas. [tis relatively common in a few parks, but locally extinct in some areas. Geoffroy’s Spider Monkey is known to occurin just one protected area, Arenal Volcano National Park in Costa Rica. Population surveys of the Azuero Spider Monkey confirmed the existence of 145 individuals in two of the three provinces where it once occurred (Veraguas and Los Santos); it is extinct in Herrera Province. It is still present in Cerro Hoya National Park and Montuoso and Tronosa forest reserves in Panama. The Black-browed Spider Monkey occurs in Barra Honda, Guanacaste, Palo Verde, Rincon de la Vieja, and Santa Rosa national parks in Costa Rica. The Ornate Spider Monkey occurs in at least 22 protected areas including Braulio Carrillo, Cahuita, Chirripo, Corcovado, and Manuel Antonio national parks and Carara Biological Reserve in Costa Rica. The Mexican Spider Monkey occurs in Palenque National Park and El Triunfo, Montes Azules, and Los Tuxtlas biological reserves in Mexico. The Yucatan Spider Monkey is found in Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary in Belize; Tikal and Rio Dulce national parks and Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala; and Tulum and Canon del Sumidero national parks and Calakmul, Ria Celestin, and Ria Lagartos biosphere reserves in Mexico. The “Hooded Spider Monkey” (A. g. grisescens) may occur in Canglon Forest Reserve in Panama, according to its supposed distribution.

Bibliography. Baldwin & Baldwin (1976a), Campbell (2000), Cant (1978, 1990, Chapman (1987, 1990), Chapman & Chapman (1990), Cuarén, Morales et al. (2008), Di Fiore & Campbell (2007), Di Fiore et al. (2008, 2011), Eisenberg (1973), Eisenberg & Kuehn (1966), Estrada & Coates-Estrada (1988), Estrada et al. (2004), Fedigan & Baxter (1984), Fedigan & Rose (1995), Ford & Davis (1992), Freese (1976), Gonzalez-Kirchner (1999), Groves (2001), Hines (2004), Kellogg & Goldman (1944), Konstant et al. (1985), Matamoros & Seal (2001), Milton (1981b), Napier (1976), Parra & Jorgenson (1998), Ramos-Fernandez & Ayala-Orozco (2003), Rodriguez-Luna et al. (1996), Rylands et al. (2006), Silva-Lépez et al. (1996, 1998).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.