CLADOMORPHINAE

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4128.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B4D2CD84-8994-4CEF-B647-3539C16B6502 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6084898 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/387F3068-D327-FF8F-FF27-EA2C27501F8F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

CLADOMORPHINAE |

| status |

|

4. SUBFAMILY CLADOMORPHINAE View in CoL BRADLEY & GALIL, 1977

Genus eponymum: Cladomorphus Gray, 1835: 15 .

Cladomorphinae View in CoL Bradley & Galil, 1977: 186.

Zompro, 2004: 134.

Otte & Brock, 2005: 32.

Cladomorphidae Brunner v. Wattenwyl, 1893: 90, 98. Bacteriinae Kirby, 1904a: 348 (in part).

Kevan, 1982: 282 (in part).

Cladoxerinae Karny, 1923: 237 (in part). Diapheromerinae, Zompro, 2001: 228 View in CoL (in part). Zompro, 2004: 139 (in part).

Phibalosomini View in CoL (SectioV: Phibalosomata) Redtenbacher, 1908: 399 (in part). Phibalosominae Günther, 1953: 557.

Phibalosomatinae, Moxey, 1971: 67.

Xerosomatinae View in CoL , Zompro, 2004: 139 (in part).

Günther (1953: 557) established the subfamily Phibalosominae (= Cladomorphinae Bradley & Galil, 1977) for sections of Phibalosomini Redtenbacher, 1908 and originally subdivided it into the four tribes Cladoxerini , Phibalosomini , Haplopodini and Cranidiini . Bradley & Galil (1977: 186) took over Günther's arrangement of the Phibalosominae and generally restricted themselves to translating his keys to the tribes into English. Taxonomic changes by these authors were limited to re-naming Günther's Phibalosominae to Cladomorphinae and Günther's tribes Phibalosomini , Haplopodini and Cranidiini to Cladomorphini , Hesperophasmatini and Craspedoniini. The new name Craspedoniini for Cranidiini Günther, 1953 was not justified and introduced because Bradley & Galil confused the type-species of Craspedonia Westwood, 1841 (see Brock, 1998b: 26), hence Cranidiini remains valid. The monophyly of Cladomorphinae sensu Bradley & Galil, 1977 seems poorly supported and the subfamily divides into at least two well recognized sub-divisions or clades, which do not appear particularly closely related, and indicate Cladomorphinae as presently recognized may not be a natural grouping (→ see comments below).

Zompro (2004) introduced several major taxonomic changes within the classification of Cladomorphinae , which however contradict all previous opinions (e.g. Günther, 1953; Bradley & Galil, 1977), extensive phylogenetic studies based on morphological features (Bradler, 2009) and molecular data ( Whiting et al., 2003). The paper by Zompro (2004) postulates numerous questionable relationships with resulting erroneous taxonomic changes and several genera are omitted. Zompro (2004: 135) transferred the three genera Aploploides Rehn & Hebard, 1938 , Diapherodes Gray, 1835 and Haplopus Burmeister, 1838 ) from Hesperophasmatini to Cranidiini . But in fact neither genus is closely related to Cranidium Westwood, 1843 , the type-genus of Cranidiini , which is proven by a wide range of morphological characters that are discussed in detail below (→ 4.2.3 and table 1). Surprisingly, the only common character for these four genera that Zompro (2004: 135) mentioned to justify his action is “the smooth and shining body”. The striking and numerous fundamental morphological differences between Cranidium and the other three genera were completely overlooked by Zompro (2004: 135). Consequently, the exclusively Antillean Aploploides , Haplopus , Diapherodes and Paracranidium Brock, 1998 are here removed from the South American Cranidiini and shown to form a well-defined clade that can be easily separated not only from Cranidiini but also from Hesperophasmatini . Therefore, Haplopodini Günther, 1953 (type-genus Haplopus Burmeister, 1838 ) is here re-established ( rev. stat. → 5) to comprise these as well as four newly described Antillean genera. Also Aplopocranidium Zompro, 2004 (Type-species: Bacteria waehneri Günther, 1940 ) from northwestern South America is not a member of Cranidiini as postulated by Zompro (2004), but in fact shows very close relation to Jeremia Redtenbacher, 1908 and Jeremiodes Hennemann & Conle, 2007 , hence was transferred to Cladomorphini by Hennemann & Conle (2010: 104). As a result, Cranidiini remains a monotypical tribe which only contains its type-genus, the very distinctive northeast South American Cranidium . Close relationship between Cranidiini to the South American Cladomorphini is indicated by features such as the presence of a gula in both sexes, the long and filiform gonapophyses VIII, presence of gonoplacs and a distinct praeopercular organ of ♀♀, specialized poculum of ♂♂ and the egg-morphology, which includes the presence of a median line. A new diagnosis and differentiation of Cranidiini is provided below (→ 4.2.3).

Although all genera retained in Hesperophasmatini by Zompro (2004), namely Hesperophasma Rehn, 1901 , Hypocyrtus Redtenbacher, 1908 , Lamponius Stål, 1875 , Rhynchacris Redtenbacher, 1908 and Taraxippus Moxey, 1971 , lack an area apicalis on the tibiae, Zompro (2004: 139) interpreted Hesperophasmatini as a subordinate taxon of the areolate subfamily Xerosomatinae (family Pseudophasmatidae ). In addition to a “similar general resemblance” of the insects Zompro (2004: 139) mentioned common features of the extremities (“interodorsal carina of the protibiae lamelliform” and “mid- and hindlegs agree completely”) and eggs (“The eggs are bulletshaped”), stating Hesperophasmatini were “…simply representing derived Xerosomatinae , in which the area apicalis is reduced“ ( Zompro, 2004: 139). As shown by Bradler (2009: 99) and confirmed herein these features do however not indicate any close relation to Pseudophasmatidae : Xerosomatinae and Zompro's placement of the tribe is not supported at all. This is also confirmed by molecular data presented by Whiting et al. (2003). In fact, close relation between Hesperophasmatini and the here newly recognized and re-established Haplopodini, which comprises genera formerly placed in Haplopodini ( Günther, 1953) or Hesperophasmatini respectively ( Bradley & Galil, 1977), is very obvious and proven by a wide range of taxonomically and phylogenetically relevant characters of the insect and egg-morphology (→ 4.2.4). Both tribes share a distribution mainly in the West Indies with only a few taxa represented in northern Central America, whereas members of the Xerosomatinae are restricted to South and Central America. Consequently, Hesperophasmatini is here removed from Pseudophasmatidae : Xerosomatinae and transferred back to Cladomorphinae . A detailed discussion is presented below (→ 4.2.4).

Zompro (2004: 135) transferred Baculini Günther, 1953 from Phasmatidae : Phasmatinae to Phasmatidae : Cladomorphinae , however without providing a diagnosis or a list of genera contained. Günther (1953: 555) treated Baculini as an Oriental tribe, but because the type-genus Baculum Saussure, 1861 was described from Brazil, the tribe is an exclusively New World taxon. Baculini is here shown to be a junior synonym of Cladoxerini Karny, 1923 ( n. syn.), since Baculum is a synonym of Cladoxerus St. Fargeau & Audinet-Serville, 1827 , the type-genus of Cladoxerini (→ 4.2.1).

The striking genus Pterinoxylus Audinet-Serville, 1838 is distributed throughout southern Central America, the northern portion of South America and also represented by one species on the southern Lesser Antilles. The genus was originally placed in Haplopodini ( Günther, 1953: 557) and subsequently moved to Hesperophasmatini ( Bradley & Galil, 1977: 188). Zompro (2004: 139) omitted Pterinoxylus in his treatment of Cranidiini and Hesperophasmatini . Detailed examination of the insect and egg-morphology of Pterinoxylus and careful comparison with taxa of Hesperophasmatini and Haplopodini have revealed several features that separate it from either tribe, e.g. the tympanal region or stridulatory organ in the basal portion of the alae of ♀♀, conspicuously displaced medioventral carina of the meso- and metatibiae, longitudinal ventral keel in the basal portion of the antennae and elongate alveolar eggs, which exhibit distinct hollow, peripheral extensions on the polar-area and capitulum. Consequently, Pterinoxylini n. trib. is here established to contain solely the striking Pterinoxylus and a detailed discussion and justification is provided below (→ 4.2.5 and table 2).

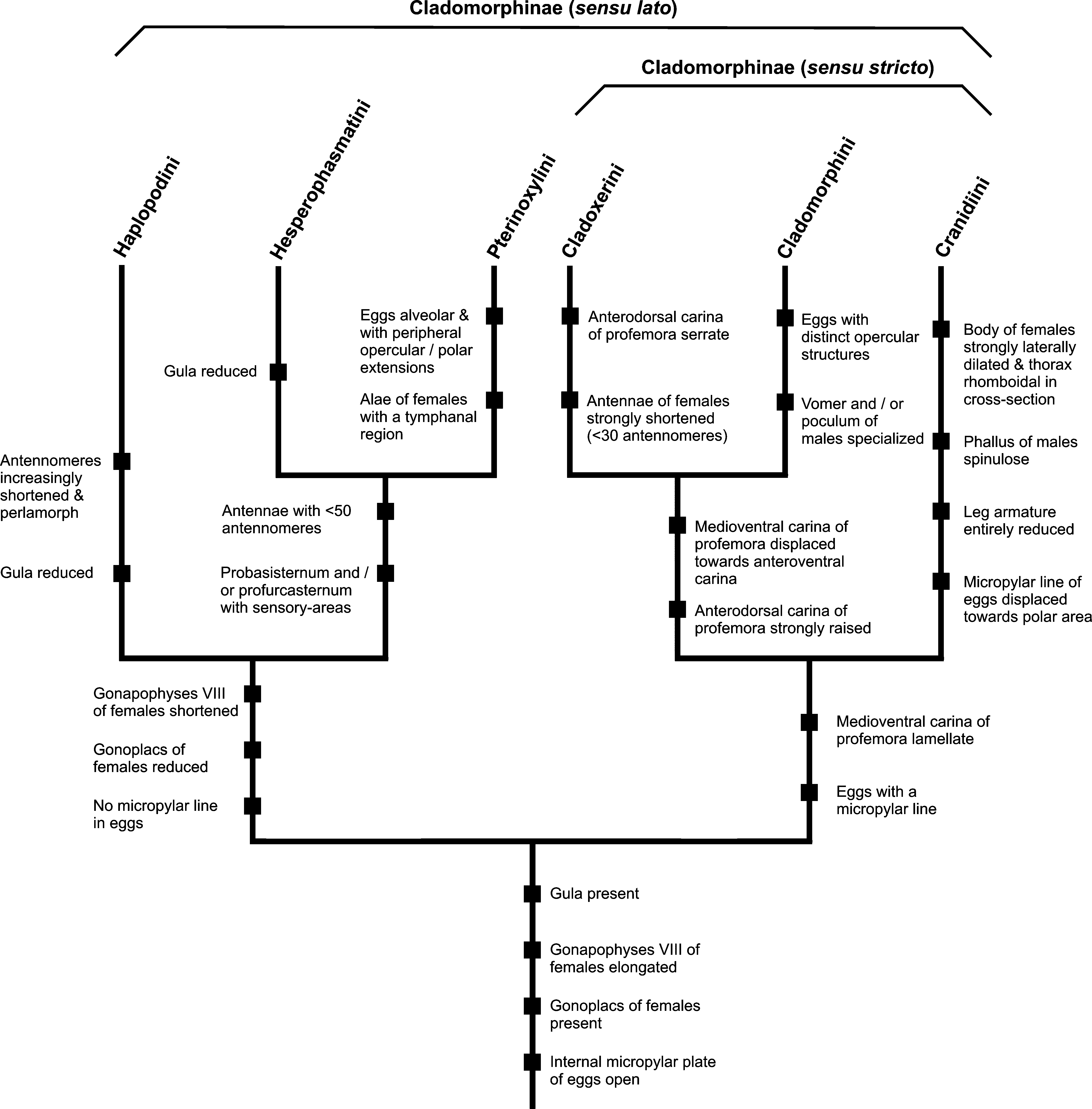

Relationships within Cladomorphinae ( Fig. 389 View FIGURES 388 – 390 ): Detailed investigation and comparison of the six tribes currently contained in Cladomorphinae indicate the subfamily as presently treated may not form a natural group and does not support its monophyly. Based on several morphological characters of both the insects and eggs two distinct groups can be recognized within the present Cladomorphinae . The first group, here also regarded as the Cladomorphinae sensu stricto, is formed by the principally South American Cladomorphini + Cranidini + Cladoxerini , while the predominantly Antillean Hesperophasmatini + Pterinoxylini n. trib. + Haplopodini form a second fairly well distinguished and presumably monophyletic clade ( Fig. 409 View FIGURES 409 ). Examination of certain taxa currently attributed to other subfamilies (e.g. Diapheromerinae and Heteronemiinae ) furthermore suggest Cladomorphinae sensu stricto to be paraphyletic (Hennemann & Conle, in preparation).

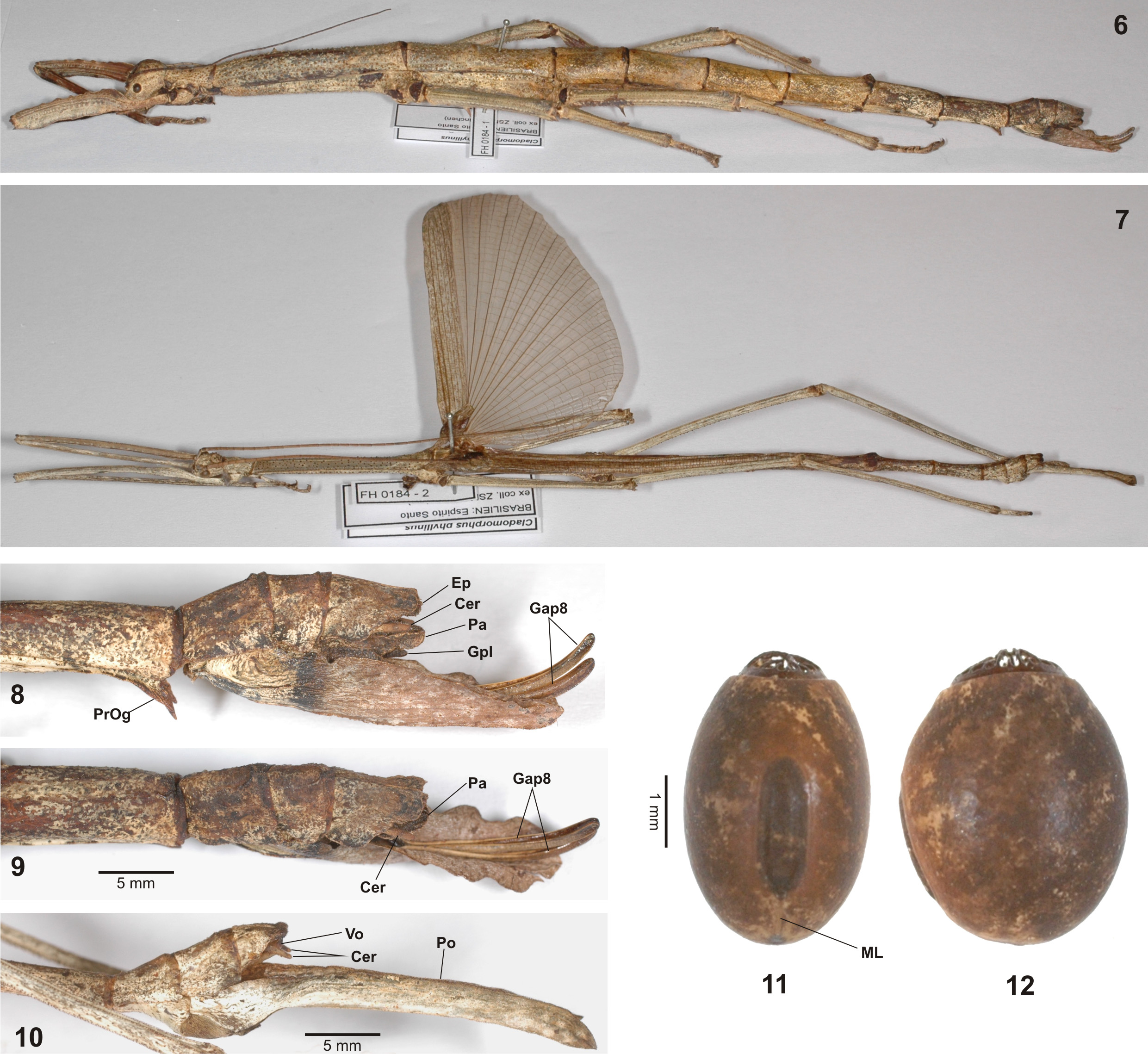

In Cladomorphini and Cranidiini the gonapophyses VIII of ♀♀ are strongly elongated, filiform and project considerably over the apex of the anal segment ( Figs. 8, 9 View FIGURES 6 – 12 , 16 View FIGURES 13 – 19 ). Gonoplacs are present ( Figs. 8 View FIGURES 6 – 12 , 16 View FIGURES 13 – 19 ). The praeopercular organ of ♀♀ on abdominal sternum VII is very distinct and usually formed by one ( Cranidiini ) or two to three ( Cladomorphini ) spiniform appendages. Males have the terminal abdominal segments specialized in various ways, e.g. an elongated sometimes tube-like or remarkably enlarged and convex poculum, strongly enlarged hook-shaped or in-curving cerci or a spinose phallus. These specializations of the ♂♂ terminalia are likely to be apomorphic character states, but this deserves evaluation by a comprehensive phylogenetic study. The medioventral carina of the profemora of Cladomorphini is very prominent, lamellate and distinctly displaced towards the anteroventral carina and the profemora are triangular in cross-section with the anterodorsal carina conspicuously raised (♀♀ in particular). There are never sensory areas on the probasisternum or profurcasternum and both tribes have a well-developed gula. The antennae are very long and filiform with strongly elongated antennomeres. The eggs possess a median line below the micropylar plate although this is fairly different in Cladomorphini and Cranidiini . The eggs of Cladomorphini possess an operculum which is similar in structure to the opercula seen in genera of Diapheromerinae : Diapheromerini : “ Phanocles -group” (→ 4.2.2), being an open and hollow net-work, and all have a ± parallel-sided micropylar plate which is open internally and exhibits a distinct median line ( Fig. 50 View FIGURES 45 – 51 ). Eggs of Cranidiini lack the aforementioned opercular structures and have a broad ovoid micropylar plate, which has a narrowing of the posterior opening before it widens into the notch. The short median line is strongly displaced towards the polar-area ( Fig. 49 View FIGURES 45 – 51 ). The striking differential characters of Cranidiini are summarized below and several of these are believed to be autapomorphies of that tribe (→ 4.2.3 and Table 1 View TABLE 1 ).

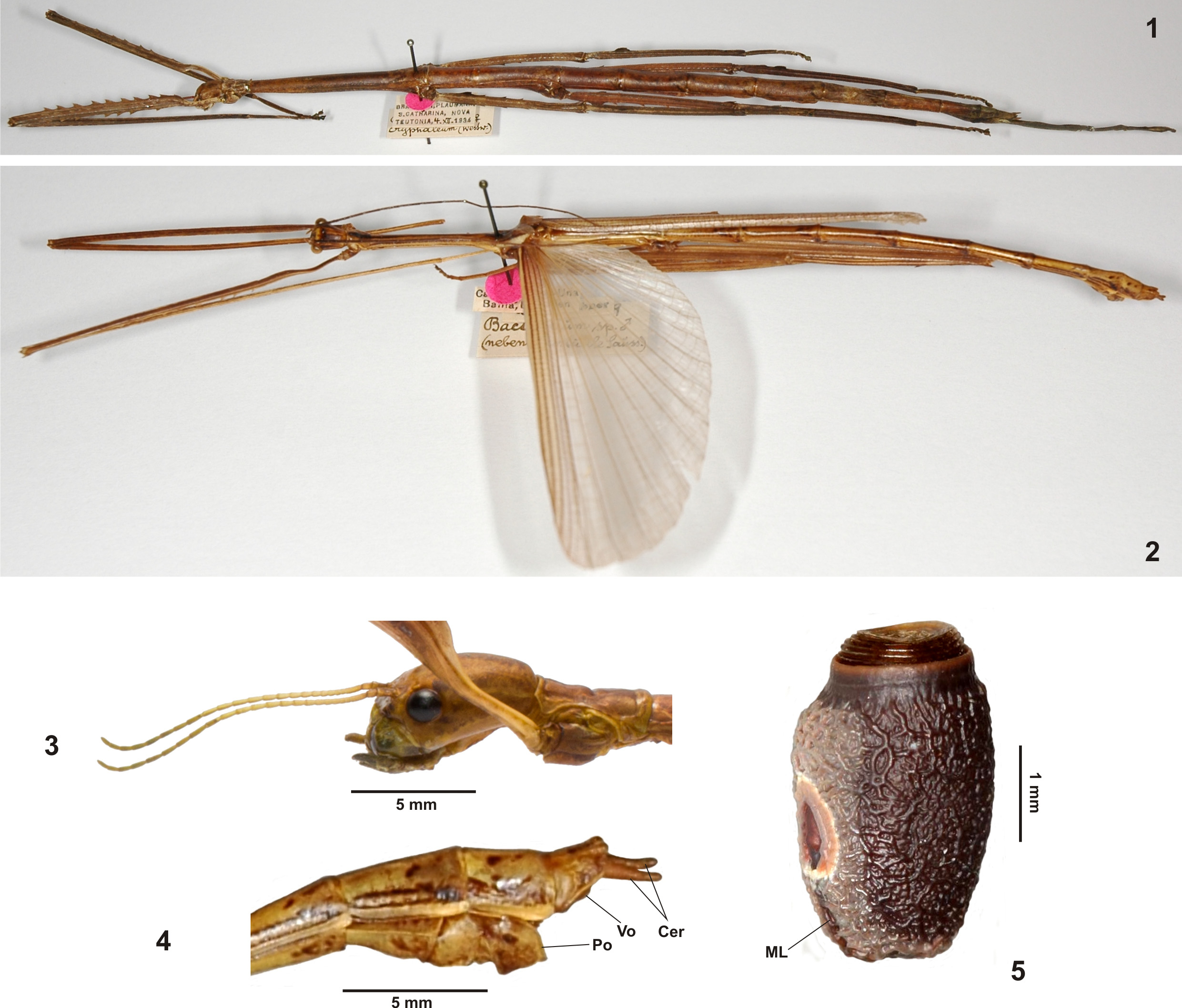

The position of Cladoxerini within the Cladomorphinae remains somewhat questionable, but several characters support it as the sister-taxon of Cladomorphinae , which consequently would place Cranidiini as the sister-group of Cladomorphinae + Cladoxerini ( Fig. 409 View FIGURES 409 ). Close relation to Cladomorphini in particular is indicated by the distinctly triangular cross-section of the profemora, which have the anterodorsal carina strongly raised and the lamellate medioventral carina considerably displaced towards the anteroventral carina. The elongated gonapophyses VIII and presence of gonoplacs in ♀♀ are shared with both Cladomorphini and Cranidiini . However, the gonapophyses VIII are increasingly less elongated and hardly project over the apex of the anal segment, which is likely to be an autapomorphy of Cladoxerini . The genitalia of ♂♂ do not show any significant specializations as in these two tribes, but as in Cladomorphini and Cranidiini there is a well developed gula. Also the egg-morphology supports close relations between these three tribes, the operculum bearing a capitular structure ( Fig. 5 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ) and the open internal micropylar plate having a median line. Females are always apterous and the anal fan of ♂♂ is transparent as in Cladomorphini and Cranidiini . The remarkably shortened antennae of ♀♀ ( Fig. 3 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ), which consist of no more than 30 antennomeres, and serrate posterodorsal carina of the profemora of both sexes readily distinguish the tribe from Cladomorphini and Cranidiini and might also be autapomorphies of Cladoxerini (→ 4.2.1).

Hesperophasmatini + Pterinoxylini n. trib. + Haplopodini are likely to form a monophyletic clade that differs from Cladomorphinae sensu stricto by a variety of characters. All three tribes lack gonoplacs and do not have conspicuously elongated or filiform gonapophyses VIII, these being short, not or hardly longer than gonapophyses IX and fully hidden under the anal segment. A praeopercular organ on abdominal sternum VII of ♀♀ is present, but it is much less developed and usually represented merely by a small wart-like swelling. The terminal abdominal segments of ♂♂ do not show any significant specializations and are fairly typical for Phasmatodea with a developed vomer. The medioventral carina of the profemora is not lamellate and more or less central on the ventral surface of the profemora. While Hesperophasmatini and Pterinoxylini n. trib. possess rough sensory-areas on the probasisternum and profurcasternum ( Figs. 28–30 View FIGURES 24 – 30 , 41–43 View FIGURES 37 – 44 ), these are lacking in Haplopodini. The presence of sensory-areas is likely to be a synapomorphy of Pterinoxylini n. trib. + Hesperophasmatini and might support a sister-group relationship between these two tribes, which would consequently place Haplopodini as the sistergroup of these two tribes ( Fig. 409 View FIGURES 409 ). Pterinoxylini n. trib. is characteristic for having a tympanal region (= stridulatory organ) in the basal portion of the alae of ♀♀, which quite certainly is an autapomorphy ( Fig. 409 View FIGURES 409 ) since it is not present in any other representative of the entire subfamily. The presence of a gula in Pterinoxylini n. trib. appears to be plesiomorphic because it is present in all three tribes of Cladomorphini sensu stricto and also distinguishes this tribe from Hesperophasmatini and Haplopodini. Females of all three tribes often possess shortened or vestigial wings and the anal fan of both sexes is mostly coloured, reticulate, tessellate or bears dark markings. The antennae are considerably more robust, on average shorter and less filiform than in members of Cladomorphinae sensu stricto (exception Cladoxerini ), either more or less oval in cross-section (Pterinoxylini n. trib. and Hesperophasmatini ) or with the antennomeres increasingly shortened and perlamorph (Haplopodini). The eggs of all three tribes agree in aspect of the morphology of the internal micropylar plate, which is open with a large and wide posterior gap but lacks a median line as in Cladomorphinae sensu stricto ( Figs. 45–48 View FIGURES 45 – 51 ). The lack of a median line is likely to represent a synapomorphy of Hesperophasmatini + Pterinoxylini n. trib. + Haplopodini. Furthermore, eggs lack the hollow net-like structures on the operculum seen in Cladomorphini and have rather short, shield-shaped or anteriorly pointed micropylar plates. The internal surface of the capsule is usually shiny sepia with the micropylar plate a contrasting white. Consequently, Hesperophasmatini + Pterinoxylini n. trib. + Haplopodini form a well separated group within Cladomorphinae as currently defined and are likely to be a monophyletic clade. This hypothesis however deserves evaluation by a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the Cladomorphinae and potentially closely related taxa.

Previous phylogenetic analyses (e.g. Whiting et al., 2003; Buckley et al., 2009; Buckley et al., 2010) have provided support for a sister-group relationship between the Cladomorphinae and the tribe Stephanacridini Günther, 1953 , an Old World clade that is today mostly restricted to some of the Pacific Islands, New Guinea and parts of Wallacea. This tribe is characterised by the strongly elongated gonapophyses VIII and well developed gonoplacs in ♀♀, the presence of a gula and a distinctly triangular cross-section of the profemora which has the anterodorsal carina conspicuously raised. As in most Cladomorphinae ♀♀ of Stephanacridini have a strongly elongated either lanceolate or spatulate subgenital plate and ♂♂ have rather basal terminalia with a well developed vomer and a pair of thorn-pads on the posterior margin of the anal segment. Most genera of Stephanacridini have shortened antennae (♀♀ in particular), that often are hardly longer than the profemora. If this sister-group relationship between Stephanacridini and Cladomorphinae ( sensu lato) supposed by e.g. Whiting et al. (2003), Buckley et al. (2009) and Buckley et al. (2010) proves true, the elongated gonapophyses VIII and presence of gonoplacs in Cladomorphinae sensu stricto as well as the presence of a gula in Cladomorphinae sensu stricto and Pterinoxylini n. trib. must be regarded as plesiomorphic, while the increasingly elongated and filiform antennae in Cladomorphini and Cranidiini in particular will have to be interpreted as apomorphic. Furthermore, this hypothesis postulates a Gondwanan origin for the Cladomorphinae and suggests invasion of its ancestors via Gondwanan land connections from the Australasian region through Antarctica to South America perhaps during the late Cretaceous or late Tertiary.

In addition to a complete taxonomic revision of Haplopodini rev. stat. at the species level, keys to the six tribes currently in Cladomorphinae , brief discussions of Cladoxerini and Cladomorphini as well as detailed new descriptions and discussions of Cranidiini (→ 4.2.3) and Pterinoxylini n. trib. (→ 4.2.5) and a more detailed discussion of Hesperophasmatini (→ 4.2.4) appear necessary and are presented below along with lists of the genera included in each of these tribes.

Tribes of Cladomorphinae Bradley & Galil, 1977:

1. Cladoxerini Karny, 1923: 237 . Type-genus: Cladoxerus St. Fargeau & Audinet-Serville, 1828 . = Baculini Günther, 1953: 555 . Type-genus: Baculum Saussure, 1862 . n. syn.

2. Cladomorphini Bradley & Galil, 1977: 189. Type-genus: Cladomorphus Gray, 1835 . = Phibalosomini Günther, 1953: 557 . Type-genus: Phibalosoma Gray, 1835 .

3. Cranidiini Günther, 1953: 557 . Type-genus: Cranidium Westwood, 1843 .

4. Haplopodini Günther, 1953: 557 rev. stat. Type-genus: Haplopus Burmeister, 1838 .

5. Hesperophasmatini Bradley & Galil, 1977: 188. Type-genus: Hesperophasma Rehn, 1901 . [Here re-transferred from Pseudophasmatidae : Xerosomatinae ]

6. Pterinoxylini n. trib. Type-genus: Pterinoxylus Audinet-Serville, 1838 .

4.1. Keys to the tribes of Cladomorphinae View in CoL

♀♀

1. Body cylindrical or oval in cross-section; abdomen not considerably dilated laterally; mesosternum not tectiform......... 2

- Body strongly flattened; abdomen prominently dilated laterally ( Fig. 13 View FIGURES 13 – 19 ); mesosternum tectiform and with a granulose longitudinal median keel ( Fig. 15 View FIGURES 13 – 19 ); NE South America..................................................... Cranidiini View in CoL

2. Antennae much longer than head and pronotum combined, consisting of>50 segments; profemora without serrations dorsally................................................................................................... 3

- Antennae distinctly shortened and hardly longer than head and pronotum combined, with <30 segments ( Fig. 3 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ); profemora serrate dorsally ( Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ); SE South America........................................................ Cladoxerini View in CoL

3. Gonapophyses VIII short, not projecting over anal segment; medioventral carina of profemora indistinct and ± central on ventral surface of femur; West Indies, Central America & Northern South America.................................... 4

- Gonapophyses VIII elongate and projecting considerably over anal segment ( Figs. 8–9 View FIGURES 6 – 12 ); medioventral carina of profemora lamellate and strongly displaced towards anteroventral carina; South America.......................... Cladomorphini View in CoL

4. No gula; alae without tympanal area; protibiae at best with single lobes dorsally; antennae round to oval in cross-section... 5

- Gula present; alae with a tympanal area (= stridulatory organ); medioventral carina of meso- and metatibiae strongly displaced towards anteroventral carina; antennae with a longitudinal median bulge ventro-basally ( Figs. 39–40 View FIGURES 37 – 44 )... Pterinoxylini n. trib.

5. With rough sensory-areas on probasisternum and/or profurcasternum ( Figs. 28–30 View FIGURES 24 – 30 ); scapus dorsoventrally flattened; profemora rectangular to trapezoidal in cross-section with anterodorsal carina at best very slightly raised....... Hesperophasmatini

- No sensory-areas on probasisternum and profurcasternum; scapus round to oval in cross-section; profemora distinctly triangular in cross-section with anterodorsal carina conspicuously raised....................................... Haplopodini

♂♂ 1. Poculum with various specializations or strongly enlarged..................................................... 2

- Poculum without specializations; small and cup or scoop-shaped................................................ 3

2. Poculum very bulgy, strongly convex and extending ventrally by more than 2x body diametre ( Fig. 17 View FIGURES 13 – 19 ); phallus spinulose; medioventral carina of profemora indistinct and central on ventral surface of femur; NE South America.......... Cranidiini View in CoL

- Poculum with two terminal teeth or posterior margin extended into a scoop, spatulate or tube-like appendage; phallus unarmed; medioventral carina of profemora distinct and displaced towards anteroventral carina; South America........ Cladomorphini View in CoL

3. Profemora shorter than head, pro- and mesonotum combined, without serrations dorsally; anal region of alae either reticulate, or plain pink to orange; West Indies, Central America & Northern South America.................................. 4

- Profemora longer than head, pro- and mesonotum combined, serrate dorsally; anal region of alae plain/transparent ( Fig. 7 View FIGURES 6 – 12 ); SE South America............................................................................... Cladoxerini View in CoL

4. With rough sensory-areas on probasisternum and/or profurcasternum; body surface dull.............................. 5

- No sensory-areas on probasisternum and profurcasternum; body surface mostly ± glabrous..................Haplopodini

5. Probasitarsus with a lobe dorsally; protibiae with the dorsal and posteroventral carinae expanded and ± lamellate or lobate; antennae with a longitudinal median bulge ventro-basally ( Figs. 39-40 View FIGURES 37 – 44 ); gula present................ Pterinoxylini n. trib.

- Probasitarsus simple; protibiae at best with small lobules dorsally; antennae round to oval in cross-section; no gula.............................................................................................. Hesperophasmatini

Eggs 1. Micropylar plate circular to spear-shaped and broadened posteriorly, covering less than 2/3 of dorsal capsule surface....... 2

- Micropylar plate elongate, slender and ± parallel-sided, covering more than 1/2 of dorsal capsule surface ( Figs. 11–12 View FIGURES 6 – 12 , 50 View FIGURES 45 – 51 )............................................................................................ Cladomorphini View in CoL

2. Internal micropylar plate with a median line................................................................ 3

- Internal micropylar plate without a median line.............................................................. 4

3. Capsule laterally compressed; micropylar plate small, <1/2 of capsule length; posteromedian notch of internal micropylar plate widely triangular ( Fig. 5 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ).................................................................. Cladoxerini View in CoL

- Capsule ovoid ( Figs. 18–19 View FIGURES 13 – 19 ); micropylar plate large,>1/2 of capsule length; posteromedian notch of internal micropylar plate narrowed before it widens into the gap ( Fig. 49 View FIGURES 45 – 51 )...................................................... Cranidiini View in CoL

4. Capsule ovoid to bullet-shaped, <2.5x longer than wide; polar-area and operculum without raised hollow extensions..... 5

- Capsule> 3x longer than wide, alveolar; polar area and operculum with hollow, peripheral or crest-like extensions ( Fig. 44 View FIGURES 37 – 44 )...................................................................................... Pterinoxylini n. trib.

5. Capsule surface and operculum covered with hairy structures ( Figs. 22–25 View FIGURES 20 – 23 View FIGURES 24 – 30 )*....................... Hesperophasmatini

- Capsule surface without hairy structures.......................................................... Haplopodini

* This character only holds true for the currently known members of Hesperophasmatini (see → 4.2.4)

4.2. Discussion of the tribes of Cladomorphinae Bradley & Galil, 1977

Below, the six tribes currently assigned to Cladomorphinae are discussed. New diagnoses and differentiations are presented for Cranidiini and Pterinoxylini n. trib.. Only brief discussions of Cladoxerini and Cladomorphini are provided, since both tribes appear paraphyletic and deserve more comprehensive study. Hesperophasmatini is discussed in more detail, but no diagnosis is provided since this would be premature and only of provisional use. The authors are aware of a large number of still undescribed species and genera of Hesperophasmatini , which would need to be incorporated for a meaningful description.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

CLADOMORPHINAE

| Frank H. Hennemann, Oskar V. Conle & Daniel E. Perez-Gelabert 2016 |

Diapheromerinae

| Zompro 2001: 228 |

Cladoxerinae

| Karny 1923: 237 |