Tainisopidae

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.156261 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6275203 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/4911878A-FFEB-FFC1-A506-FE2AFB280294 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Tainisopidae |

| status |

|

Tainisopidae View in CoL fam. nov.

“Enigmata” Poore and Lew Ton, 2002: 345.

Type Genus. Tainisopus Wilson and Ponder, 1992 ; here designated.

Etymology. Tainisopidae is derived from name of the type genus, but the genitive stem is not used to allow a shorter, less cumbersome name.

Diagnosis. Head dorsal surface clearly demarcated from lateral surface by cuticular ridge; frons with thin ridge between antennae, not directly connected to clypeus. Coxa VI oopore on ventromedially produced margin. Penes attaching to coxae VII by triangular broadly flexible region (not on separate sclerite). Pleonites 15 flexibly articulated, elongate, lacking pleurae, pleonite 5 enlarged. Pleotelson freely articulating with pleonite 5. Antennula article 1 strongly curved laterally, secondary flagellum rudimentary (minute setose article on article 3 anteromedial distal margin). Antenna protopodal article 1 present, article 3 with rudimentary circular scale surrounded by articular membrane. Mandible distal gnathal margin rotated to approximately right angle to proximal body; molar distally truncate, distal margin with arclike dentate ridge. Pereopod I with major reflexive hinge between propodus and dactylus, propodus with row of biserrate robust setae in palm region. Pereopods IIIII with major reflexive hinges between carpus and propodus, carpus with row of robust setae in palm region; pereopods IVVII without major reflexive hinges. Pereopods IV coxae with oostegites. Pleopodal endopod I of both sexes single flattened lobe, endopods IIIV in male and IIV in female divided into 2 or 3 lobes. Pleopod II appendix masculina with laterallyfacing groove on dorsal surface, with denticles on dorsal ridge of groove; basal lamella absent. Uropod protopod longer than broad, projecting posteriorly.

Description. Head freely articulating with pereonite 1, weakly recessed into pereonite 1; anterior margin medially concave; interantennal rostrum absent, interantennular ridge arclike, shorter than antennal basal diameter, connecting ventrally to rounded projection between antennae dorsal to clypeus; eyes absent; cervical groove absent; mandible inserting into anterior half of ventral surface; maxillipeds inserting at posterolateral margin. Foregut ventral floor with laterally curving anterior filter plate. Pereonites 27 similar in shape, lateral margins linear in dorsal view. Pleonites 15 total length more than half length of pereon; pleonites 14 lengths subequal; lateral margins not produced ventrally, pleurae absent; articulations flexible (able to rotate in vertical and transverse axis). Pleotelson flattened, width greater than depth, dorsal cuticle smooth; dorsal uropodal ridge absent.

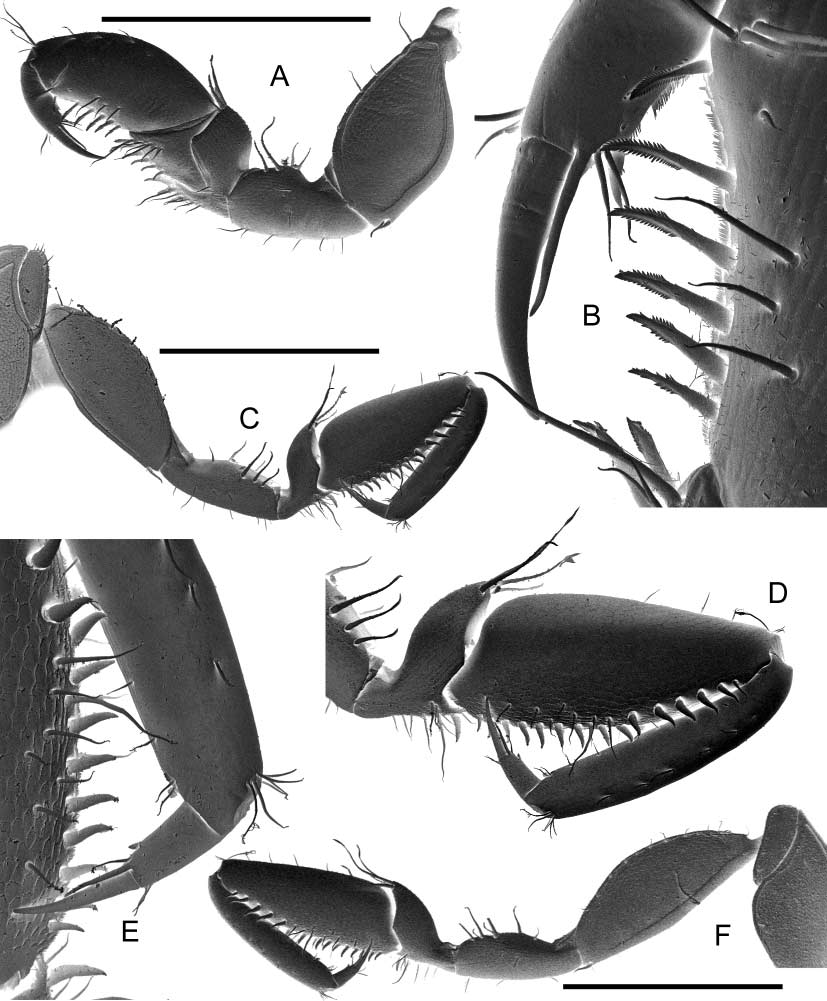

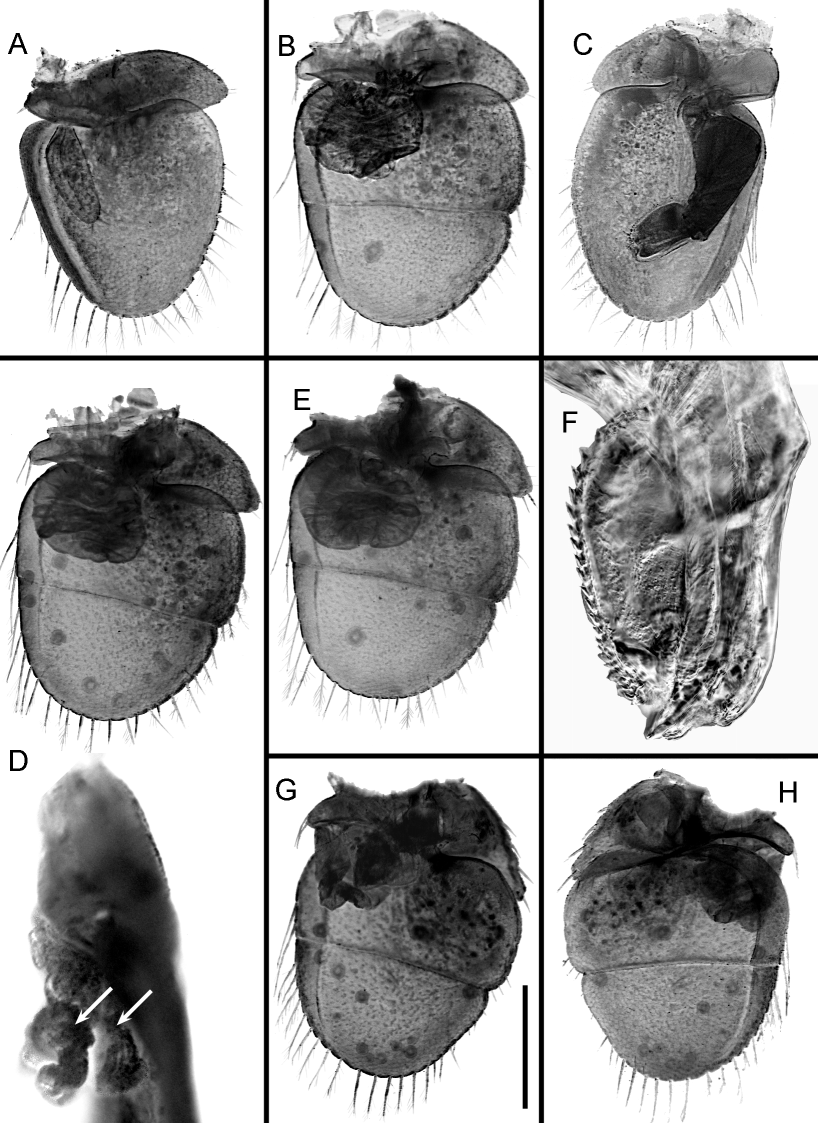

Antennula length 0.170.28 body length, emerging near cephalic midline; article 4 shorter than article 3 and article 5, flagellum with 1626 articles in adults. Antenna length 0.31 0.57 body length in adults; proximal article large and distinct; flagellum with 3154 articles. Mandible incisor processes dentate, with 45 cusps; left lacinia mobilis robust, with 3 cusps and protruding proximal articular condyle; right lacinia mobilis with 2 arclike dentate plates, anterior plate smaller than posterior plate; spine row positioned at angle (i.e., not parallel) to gnathal axis, right side with 1 less spine than left side; dorsal condyle narrower than molar process, tapering, distally rounded; palp robust, with 3 articles, article 3 distal margin weakly curved, with ventral row of robust denticulate setae. Maxillula lateral lobes with multiple denticulate robust setae; medial lobe medial margin with large medial pappose setae (4 in observed species), medial margin multiple setae in ventral and dorsal rows. Maxilla inner lobe with dentate and setulate setae on distal medial margin, proximal medial margin with fine setae only. Maxilliped elongate and thin, length approximately 5 width, with distinct narrowing proximal to palp insertion, endite extending to or beyond palp article 2. Coxa I fused to pereonite 1, coxae IIIII broadly attaching to tergites, not covering entire lateral surface, coxa III longer than coxa II; coxae IVVII broadly attaching to tergites, covering entire lateral surface. Pereopods IIVII propodus posterodistal margins with articular plates. Pereopod I propodus simple, somewhat inflated, propodal palm concave, without major spines or projections, with row of robust setae; carpus triangular in lateral view, dorsal margin axially compressed to thin flange, ventral margin deeply inserting into merus proximally; merus dorsal margin enlarged, projecting, distally concave, adjacent to propodus. Pereopods IIIII with major reflexing hinge between propodus and carpus; propodus much longer than wide, tubular, without robust setae on oppositional (ventral) margin; carpus dorsal margin distally inflated, tapering proximally, palm convex, with row of robust setae; merus dorsal margin enlarged, projecting, distally concave, adjacent to dorsal margin of carpus. Pereopods IVVII all segments longer than wide. Pleopod exopods broad and lamellar, width near length or only slightly less; exopod I uniarticulate, IIV partially biarticulate (divided by suture line on anterior/ventral face); suture lines, where present broad, margins not constricted at junction. Uropods slightly flattened dorsally, wedge shaped in crosssection with deepest part on lateral side; endopod longer than exopod, subcircularoval in crosssection.

Discussion. The Tainisopidae fam. nov. is here classified as Flabellifera (sensu lato, cf. Wilson 1998, 1999). This well recognised ( Martin & Davis 2001) but poorly defined ( Wägele 1989, Brusca & Wilson,1991) suborder name is retained here, despite being omitted by Poore (2002). In this broader concept, Flabellifera includes the previous suborders Valvifera, Anthuridea, Gnathiidea and Epicaridea as subordinate taxa. The suborders established or recognised by Poore (2002), viz. Cymothoida (including anthurideans, gnathiideans and epicarideans), Limnoriidea, Sphaeromatidea (including serolideans) and Valvifera, are used here as infraorders, without change to their names. Defined in this way, Flabellifera corresponds to a monophyletic group ( Wägele 1989, Brusca & Wilson 1991) and resembles the original composition of Sars (1897). This classification identifies four major clades of the Isopoda: Phreatoicidea, Asellota, Oniscidea and Flabellifera. Scutocoxifera Dreyer & Wägele, 2002 , whose apomorphies and existence in the cladograms were noted by Brusca & Wilson (1991), unites the latter two suborders. In the absence of a fully phylogenetic system of classification, Scutocoxifera does not fit comfortably into the traditional system, and is not used here. By recognising Flabellifera as a suborder in this broader definition, numerous separate but related suborders are avoided, and a widely used name ( Martin & Davis 2001) is retained.

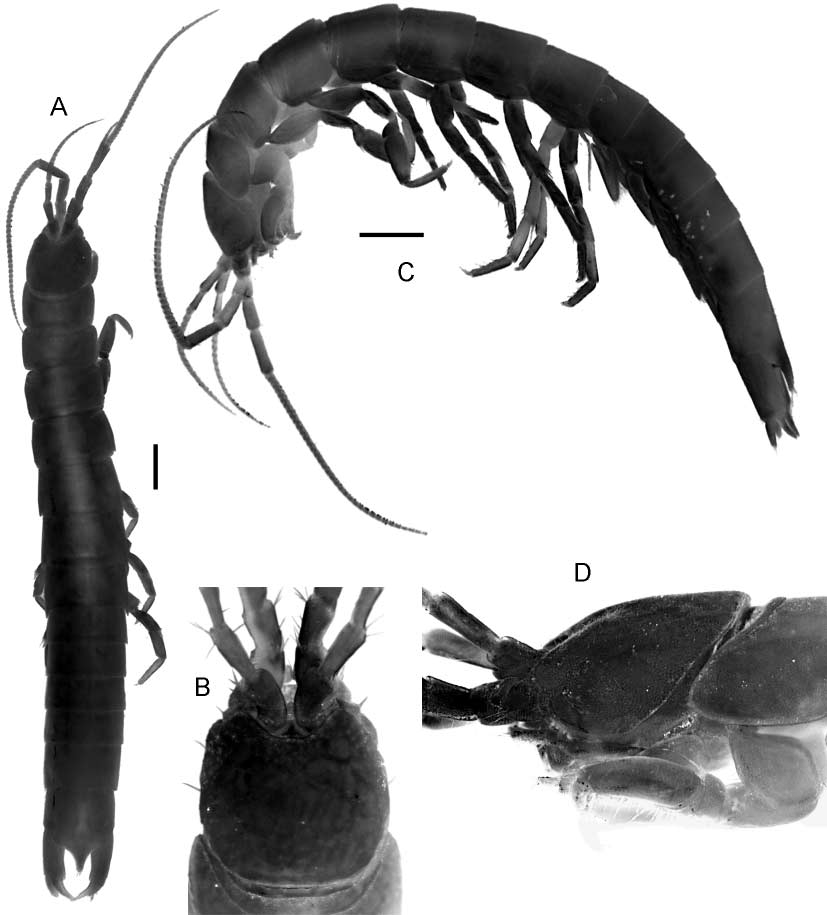

Flabelliferan apomorphies found in Tainisopidae include features such as large lateral coxae broadly attached to the tergites ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 C; apomorphy of the Scutocoxifera, see Dreyer & Wägele 2002) and broad natatory pleopods with transverse sutures in the broad biarticulate exopods ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). Phreatoicidea and Asellota have narrower pleopodal protopods, and the Oniscidea lack exopodal sutures. The new family has oostegites on pereopodal coxa V, which is found in many flabelliferans, whereas Phreatoicidea and Asellota lack an oostegite on coxa VVII. In Tainisopidae , pereopods IIII are modified for grasping (prehensile), and pereopods IVVII are less modified walking legs ( Fig. 45 View FIGURE 4 ). These latter features describe a tagmosis of the body into two sections: the first 3 pairs of pereopods differ from the posterior 4 pairs, both in shape and orientation. The Flabelliferans, as a general body plan, have pereopod IV in the posterior tagma, more closely resembling a walking leg. Deviations from this plan are common, and whether the Sphaeromatidea fit this pattern requires further evaluation. Pereopod IV is part of the anterior tagma in Asellota and Phreatoicidea, which may be the plesiomorphic condition owing to its correspondence to the division of the body during ecdysis. The Oniscidea have no pereonal tagmosis, possibly owing to their terrestrial ambulation. Antennula article 1 curves laterally in tainisopids ( Fig. 2 C), although not as pronounced as in many flabelliferans. The foregut of Tainisopus has the form seen in Sphaeromatidae or Limnoriidae , a laterally curving ventral filter plate (unpublished data; Wägele 1989), while the basally derived groups Asellota and Phreatoicidea have longitudinallyoriented ventral filter plates ( Wägele 1989). The mandible shows a pattern typical of many flabelliferans with the distal gnathal edge rotated approximately at a right angle to the proximal mandibular body ( Fig. 2 F).

The question of the relationships of the Tainisopidae within the Flabellifera remains. The classification (modified as above from Poore 2002) can be used as a starting point. The infraorder Cymothoida Wägele, 1989 is defined by distinctive modifications to the mouthparts for carnivory or parasitism and by broad and flat uropods that are lacking in the Tainisopidae . The unique uropods, pleotelson and pleonites (uropods forming a pleopodal cover on a unified pleon) in the infraorder Valvifera removes this group from consideration. The substantial modifications of the head (eyes and mandibles displaced to posterolateral margin of head) and pleotelson (including reduction and fusion) in the infraorder Sphaeromatidea Wägele, 1989 preclude classifying the Tainisopidae in this infraorder. This consideration leaves the infraorder Limnoriidea Poore, 2002 (p. 196, authorship corrected), which currently contains the divergent families Limnoriidae , Keuphyliidae and Hadromastacidae . The latter taxon may be a highly modified sister group to the Limnoriidae , and placement of the Keuphyliidae in this group is unconvincing. For these reasons, comparison with the Limnoriidae seems most productive. Tainisopidae share with Limnoriidae features that could be regarded as plesiomorphies, including largely unmodified pleonites with pleonite 5 being longer than pleonites 14, thick and narrow uropodal protopods and rami (as opposed to broad flattened rami seen in the other infraorders), head not substantially embedded into pereonite 1, maxillipeds set on the posterolateral margin of the head and epistome not present. Both taxa share the shape of the maxilliped, one feature that may be derived: an elongate narrow basis with a welldeveloped narrow endite; the basis is laterally concave between its origin and the insertion of the palp, thus appearing to have a waist. This feature is not found in the Keuphyliidae , which has a more plesiomorphic form of the maxilliped with a broader, less elongate basis and endite. The maxilliped of the Hadromastacidae resembles that of the Limnoriidae .

Limnoriids are specialised for boring into marine plants or wood and tainisopids are freeliving hypogean animals, so numerous details differ between the two families, particularly in the shape of the mandibles, and details of the pereopods and the pleotelson. The similarity between the tonglike uropodal endopod of Pygolabis gen. nov. and Limnoria Leach, 1814 is striking, although these forms are almost certainly not homologous: Tainisopus and Paralimnoria Menzies, 1957 have unspecialised endopods, and the pleotelson of Pygolabis is substantially different from that of the limnoriids. Nevertheless, the tonglike endopods of Pygolabis and Limnoria suggest an underlying skeletomusculature that would support such adaptations. The thin, elongate body of the limnoriid genus Lyseia Poore, 1987 is similar to the tainisopids, although the homologies of the individual somite shapes are less certain. Of the apomorphies in the diagnosis of the Limnoriidea Poore, 2002, only the reductions of the mandibular gnathal edge, which are undoubtedly adaptations to chewing celluloserich substrates in the Limnoriidae , differs from the Tainisopidae . Other characters in Poore’s (2002) diagnosis allow inclusion of the Tainisopidae in this infraorder. Given a lack of strong evidence to the contrary, the Tainisopidae is placed among the Limnoriidea Poore as a plesiomorphic member of the group.

Members of the Tainisopidae can be distinguished from other flabelliferan taxa using several characters. The frons of the head of many, but not all, flabelliferans have a welldefined median ridge between the antennae connected to the clypeus (epistome). The tainisopids, however, have a weakly developed, thin bar that does not connect to the clypeus ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 B in dorsal view, see also Wilson & Ponder 1992, fig. 2E). The penes are attached to triangular extensions of seventh coxae ( Fig. 6 A), which is unusual among most isopods (Wilson 1991). Both genera of the Tainisopidae have an antenna article 1 and a tiny circular scale surrounded by articular membrane on article 3 ( Fig. 2 B). This rudimentary scale is unlike the projecting and articulated scale of the Asellota. These two different forms of the scale are homologous only by position, and not by special similarity. The rudimentary scale may occur elsewhere among the flabelliferans, given that this region is not generally illustrated. The molar process has the plesiomorphic form for the Peracarida ( Richter et al. 2002, Edgecombe et al. 2003) but the dentate ridge on anterodistal margin ( Fig. 2 EH) is possibly a derived feature. The appendix masculina has a dorsal groove and lateral denticulate ridge ( Fig. 6 BD, 7F; Wilson & Ponder 1992: fig. 8C), and no lamellar basal part, unlike many flabelliferans ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 C). The reflexive hinges of pereopods IIIII ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 CD), which allow the carpus and propodus to oppose each other, are unusual among most isopods; many flabelliferans with prehensile pereopods IIIII have the major articulation between the dactylus and propodus, thus resembling pereopod I. The divided endopod lobes of the pleopods ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 B, DE, G) are also unusual and diagnostic for the family. The posteriorly projecting, elongate uropods ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A, 6 EG) are distinctive, although a variety of forms are found among other flabelliferans.

The original description of Tainisopus suggested that the form of the pleotelson was similar to many taxa in the Flabellifera. The addition of Pygolabis gen. nov. complicates this concept, because its pleotelson is more like that seen in more basally derived isopods, such as the Phreatoicidea ( Erhard 1998), with an elongate preuropodal part containing powerful musculature attached to the uropods. These similarities are likely to be independent innovations because, in Pygolabis , the uropods rotate in a horizontal plane to bring the endopods together, while phreatoicidean uropods owing to their highly vaulted pleotelson rotate in a vertical plane ( Erhard 1999). Because Tainisopus and Pygolabis show divergent forms of the pleotelson, the plesiomorphic state of the pleotelson in the family remains uncertain.

Among other isopods that might be found in hypogean fresh water aquifers, members of Tainisopidae are easily recognisable by their elongate, highly flexible bodies and rapid swimming ability. Although Tainisopidae might be confused with hypogean Cirolanidae (such as Turcolana Argano & Pesce, 1980 ), they lack broad flat uropods and bladelike mandibular molars of the cirolanids. Phreatoicidea are found in similar environments in Western Australia ( Knott & Halse 1999; Wilson & Keable 1999), but the pleopods, coxae and body forms are distinctively different in the two groups. Neither Cirolanidae nor Phreatoicidea have pereopods IIIII with major reflexive hinges between the propodus and carpus, as is observed in the Tainisopidae . The pleotelson of phreatoicideans is highly vaulted, even in the hypogean forms, while the tainisopid pleotelson has a low lateral profile, much wider than deep. The coxae of Tainisopidae are broad, without the posterior tergites participating in the lateral margin of the posterior pereonites, while the lateral margin of phreatoicidean pereonites includes fairly compact coxae surrounded by tergite.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.