Phidippus pacosauritus, Edwards, 2020

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.7171154 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A86E22D-F943-411D-927C-85FA0A0DDB78 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9CFAA9DC-5FAC-43D0-B172-9DC8A2F3831A |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:9CFAA9DC-5FAC-43D0-B172-9DC8A2F3831A |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Phidippus pacosauritus |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Phidippus pacosauritus View in CoL , sp. nov.

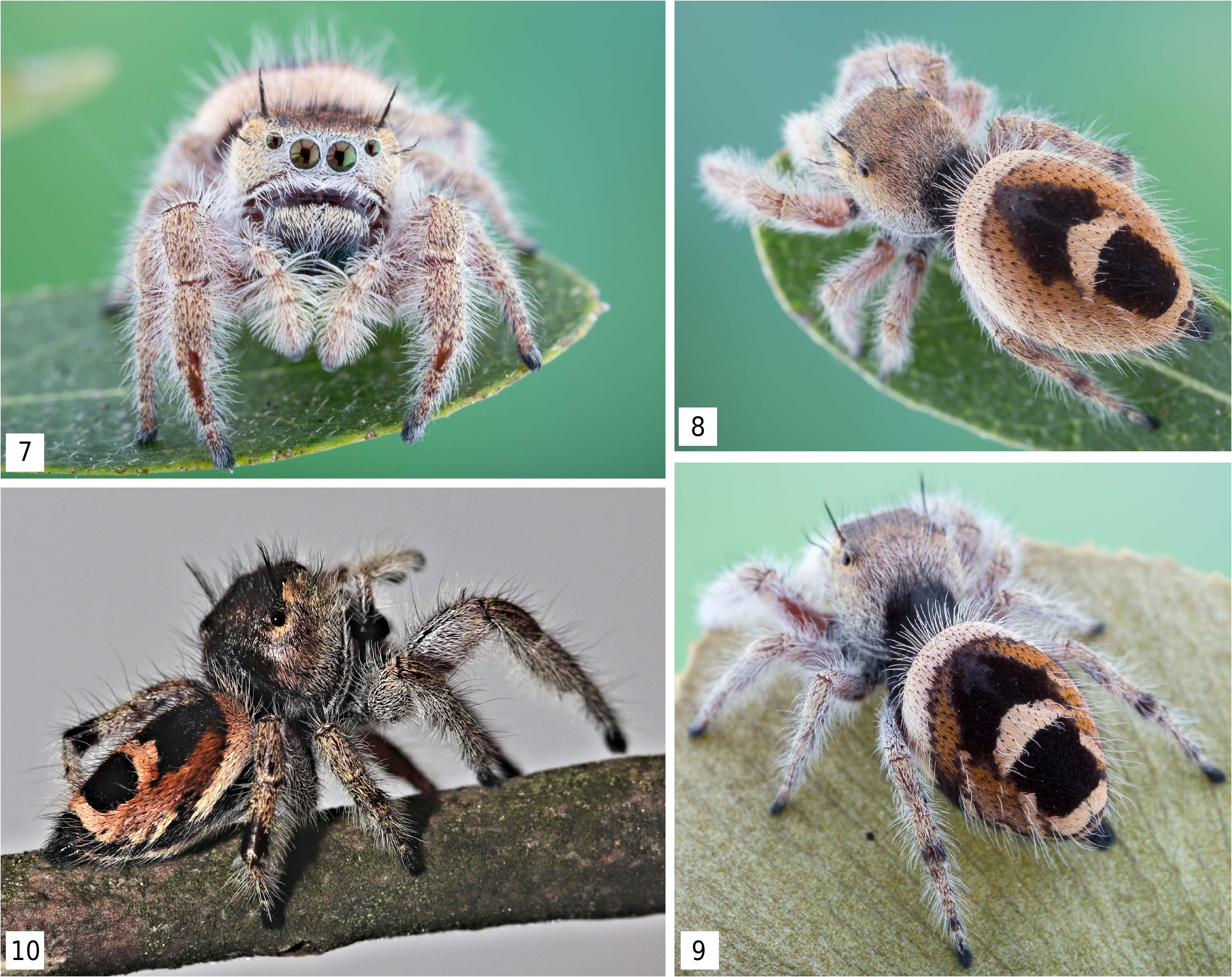

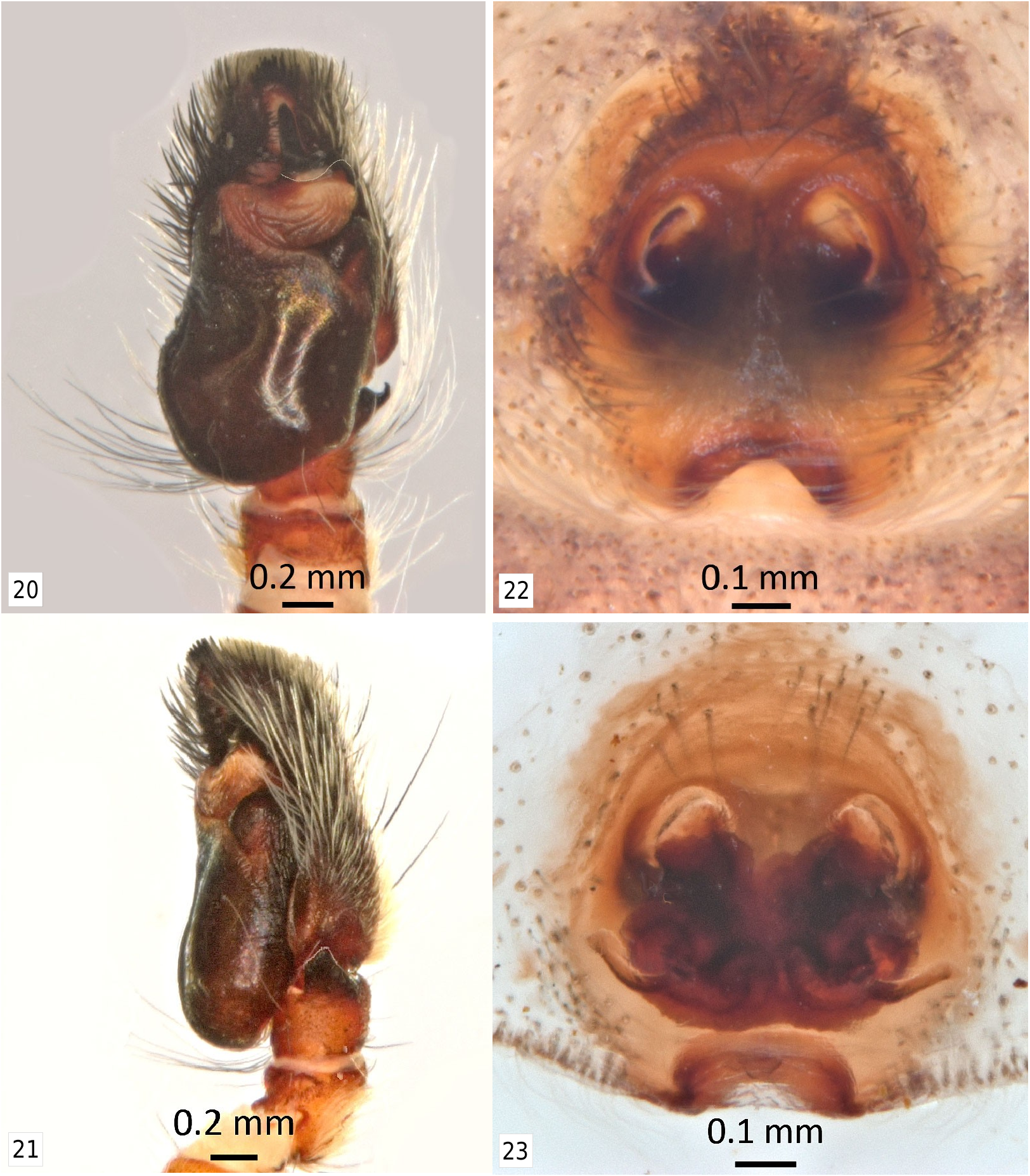

Figures 1-23 View Figures 1-2 View Figures 3-6 View Figures 7-10 View Figures 11-12 View Figures 13-15 View Figures 16-19 View Figures 20-23 , 26 View Figures 24-29 , 36 View Figures 34-37 , 42-43 View Figures 42-43

Type Material. Holotype male and paratype series all from type locality, MEXICO: Sinaloa: Mazatlán, Paco's Reservera de Flora y Fauna , tropical deciduous forest (‘selva baja caducifolia’), on opuntia and sotal, 1 July 2019, coll. Colin Hutton. Other specimens represented by online photographs have been found on trees and shrubs; in this habitat, trees are often only 4-10 m high, or rarely to 15 m (Albert van der Heiden, personal communication 2020). All specimens in the type series were reared from 2-3 eggsacs from two females collected on this date. The holotype, allotype, and several other paratypes of each sex are deposited in the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México ( UNAM). The remaining paratypes are deposited in the Florida State Collection of Arthropods ( FSCA), Gainesville .

Etymology. Based on the names of the two gentlemen named Francisco, nickname ‘Paco’, from the type locality (see Acknowledgments), and the Latin word auritus = having long ears. To be translated as “Pacos’ long-eared Phidippus ;” as a common name, “Pacos’ long-eared jumper,” or, in Spanish, “saltarina orejuda de los Pacos.”

Diagnosis. Both sexes with distinctive color patterns including short wide median triangular mark on abdomen, which along with white leg I fringes in male, are somewhat similar to P. adonis , but male does not have red face of the latter species. Males can be distinguished from P. adonis , P. arizonensis , and P. cruentus by the smaller lateral carapace projections, and from the latter two species by having white rather than yellow foreleg fringes; additionally can be distinguished from P. arizonensis by having contrasting ventrolateral abdominal stripes like P. cruentus rather than a black ventral abdominal fringe; and embolus distal end relatively thick, most similar to P. mystaceus . Female epigyne similar to P. cruentus , lacking flaps, but median part with more angulate lateral edges.

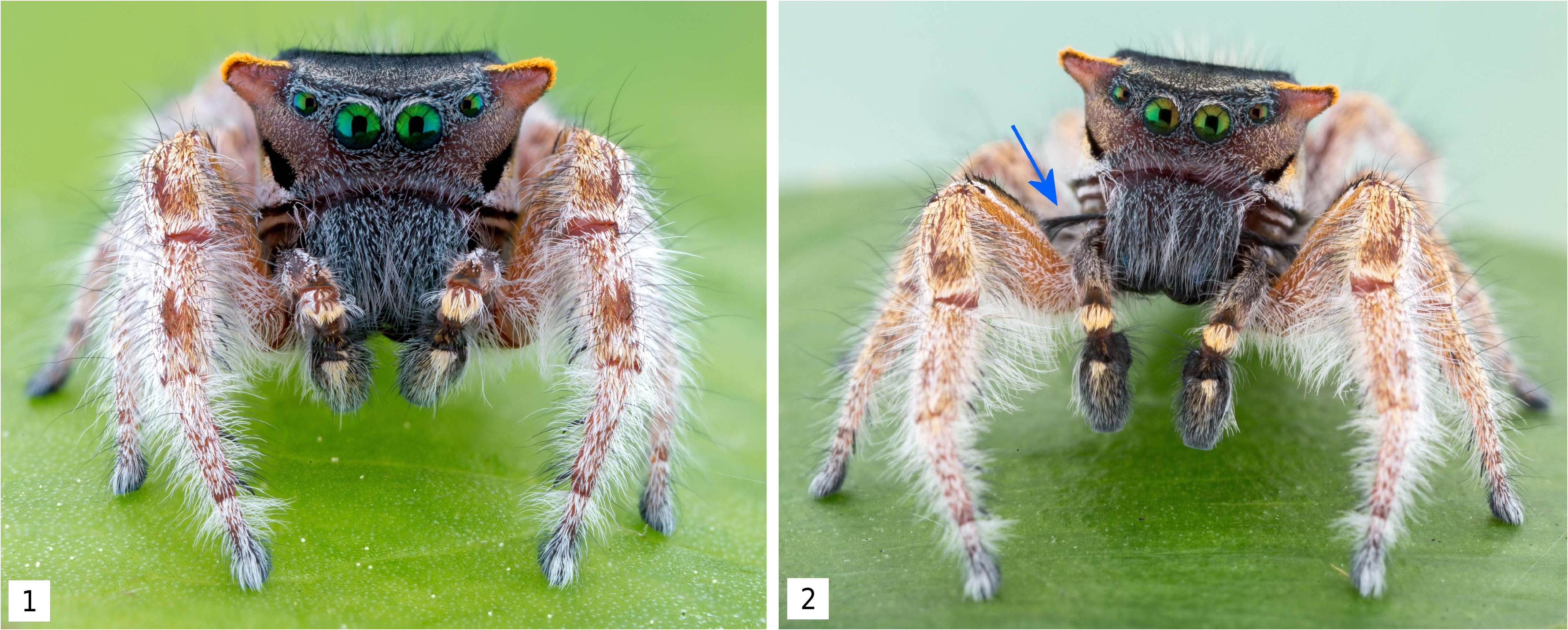

Description. Male ( Figures 1-6 View Figures 1-2 View Figures 3-6 , 13 View Figures 13-15 , 16 View Figures 16-19 , 20-21 View Figures 20-23 , 26 View Figures 24-29 , 36 View Figures 34-37 , 42-43 View Figures 42-43 ): body length H = 9.70, range = 9.04 (9.57) 10.13; carapace length H = 4.40, range = 4.40 (4.54) 4.79; carapace width H = 3.61, range = 3.55 (3.64) 3.80. Carapace mostly black, but face integument dark reddish brown. Face area mostly covered with darker gray scales as an anterior ocular band above anterior eye row and across clypeus, with scattered lighter gray and orange scales on slightly expanded lower ‘cheek’ area. Anterior ventrolateral areas of the carapace with two iterations of alternating white/black banding, the lower black band appearing as an extension of the black clypeal/cheliceral border in direct facial view. Gray scales continue onto upper part of chelicerae, and rest of chelicerae covered with long gray setae. Chelicerae with metallic blue integument, but mostly this is not visible due to the scale and setal cover. Upper ‘cheek’ area narrowed and extended dorsolaterally to a blunt point (more like an ‘ear’); anterior surface convex, lower part light gray to cream colored, upper part reddish brown, or all reddish brown; posterior, dorsal, and upper lateral surface of ‘ear’ covered with orange scales. No long carapace setal tufts ( Figures 1-2 View Figures 1-2 ). Ventral cephalothorax with black chelicerae, endites, labium, sternum, coxae, and basal half of trochanters. Integument of remaining leg segments reddish brown. Legs generally covered with white scales and setae, except some pale orange scales on distal edges of femora and bases of patellae, and a dorsal bare spot on distal end of tibiae IV. Dorsal abdomen black with orange basal band followed by a pair of short, posteriorly diverging orange bands of variable width (presumed to represent spot pair I), spot pair II fused (typical for genus) into a short, wide, orange triangle, and an orange transverse band near posterior (presumed fused spot pair IV, atypical for genus) ( Figures 3-6 View Figures 3-6 ); spot pair III appears to be unrepresented, although some specimens show a small orange spot far laterally in this position, but one well-marked male shows this to be more likely the tip of lateral band IV ( Figure 6 View Figures 3-6 ; see Notes on Morphology below). Ventral abdomen black or dark tan with ventrolateral narrow rusty reddish brown band each side, usually edged with white or yellow, and if median area not entirely black, some medial symmetrical gray markings and/or a darker gray median stripe present ( Figures 13 View Figures 13-15 , 16 View Figures 16-19 ). Spinnerets dark reddish brown. Entire leg I covered with white setae extending into long fringes especially on the venter; also a cover of white scales on the distal segments except for patches of orange scales on dorsum of patella and tibia. Femur I anterior surface covered with orange scales except for two longitudinal white scale bands, one medial and one ventral; dorsum with a black stripe that ends subdistally (with the end of the median white band extending around it at the distal end of the segment like P. arizonensis ( Figures 1-2 View Figures 1-2 , 26 View Figures 24-29 ; compare to Figure 27 View Figures 24-29 ), from which a long black setal tuft emerges angling medially from the basal third ( Figures 2 View Figures 1-2 , 36 View Figures 34-37 ). Palpi reddish brown proximally to black distally with short white dorsal and lateral markings on the femur, some orange scales on the distal edge of the femur and dorsum of the tibia, a dense patch of pale orange scales on the dorsum of the patella, and pale orange or white scales medially on the dorsal base of the cymbium. Cymbium also with intermixed long white setae medially continuing to near the distal end, with some orange and white setae to either side ( Figures 1-2 View Figures 1-2 , 26 View Figures 24-29 ). The ventral side of the palp has the wide but shallow ventral part of the embolic haematodocha (‘salticid palea’) like P. arizonensis , a distal sclerotized ridge that is very narrow until it widens laterally, and an apical part of the embolus that is fairly broad and clearly twisted, but tapers distally like P. mystaceus , unlike P. cruentus that does not taper ( Figure 20 View Figures 20-23 ).

Female ( Figures 7-10 View Figures 7-10 , 14-15 View Figures 13-15 , 17-19 View Figures 16-19 , 22-23 View Figures 20-23 ): body length A = 11.63, range = 10.23 (10.77) 11.63; carapace length A = 4.44, range 4.18 (4.62) 5.18; carapace width A = 3.80, range = 3.63 (3.83) 4.26. Carapace except black posterior thoracic slope mostly covered with light tan scales, darker tan to dark brown scales on dorsal eye field, light gray scales immediately surrounding anterior eye row, and a row of long white setae on the narrow clypeus. Four typical large setal tufts on the anterior quarter of the carapace, an exceptionally long dorsal pair and a lateral pair. Chelicerae with light tan band of scales basally, then metallic blue or blue-green for remainder of length ( Figure 7 View Figures 7-10 ). Dorsal abdomen with basal band, spot pair II, and spot pair IV like male except they are very light tan in color, as are lateral bands II-IV, that intersect with or are mostly covered by wide lateral stripes. These stripes are typically darker tan in color, but may be reddish tan or reddish in color ( Figures 8-10 View Figures 7-10 ). Ventral abdomen similar to male, except with a broader reddish brown stripe each side, medial gray markings coalesced into median stripe, and a darker narrow median stripe within it ( Figure 14 View Figures 13-15 ). Another variation is three gray stripes on a pale background, so that it appears there are four pale stripes, with darker areas of varying intensity ( Figures 17-19 View Figures 16-19 ); or the venter may be mostly covered with tan and gray scales ( Figure 15 View Figures 13-15 ). Legs and palps with reddish brown integument covered with white setae and light tan scales.

Both sexes with leg macrosetae typical for the genus (see Edwards 2004). As is usual for many salticids, the color pattern of the penultimate male ( Figures 11-12 View Figures 11-12 ) is quite similar to that of an adult female. It appears that incipient ‘ears’ have already formed on the penultimate male, as a slight protuberance can be seen on each side of the upper carapace covered with a small patch of pale orange scales.

Notes on Morphology. One exceptionally well-marked male ( Figure 6 View Figures 3-6 ) shows lateral bands II-IV, suggesting that the small dorsolateral spot pair between spot pairs II and IV is the tip of lateral band IV (confirmed by comparing to the female lateral bands – Figure 9 View Figures 7-10 ). This specimen also has the most development of spot pair I. Lateral band III is slightly shorter than II and IV in both sexes, as is usually the case. For reference, the so-called basal band is considered to be the anteriorly fused pair of lateral band I; some specimens of other species are missing the middle fused part of the basal band, which can be seen in these cases to consist of two lateral bands.

with red dorsal abdominal scales, but note the incipient ‘ears’ formed on the upper lateral carapace with a narrow cover of pale orange scales. Photo credits: David Hill.

Distribution and Habitat. Only known from the type locality in western Mexico. The habitat where the species was found extends through much of lowland southwestern Sinaloa (also north central Sinaloa and central Sonora), which might be expected to approximate the range of this species. This coastal range is generally north and west of the area where P. cruentus is known to occur, although both seem to be distributed on the west side of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range. The dividing line between them seems to roughly correspond with the Rio San Pedro, and P. pacosauritus seems to live in somewhat drier tropical deciduous forest than P. cruentus , although the latter species has also been taken from cactus, agave, and small trees and shrubs in an open grassy area where the forest had mostly been cleared (C. Hutton, personal communication 2020, and personal observation).

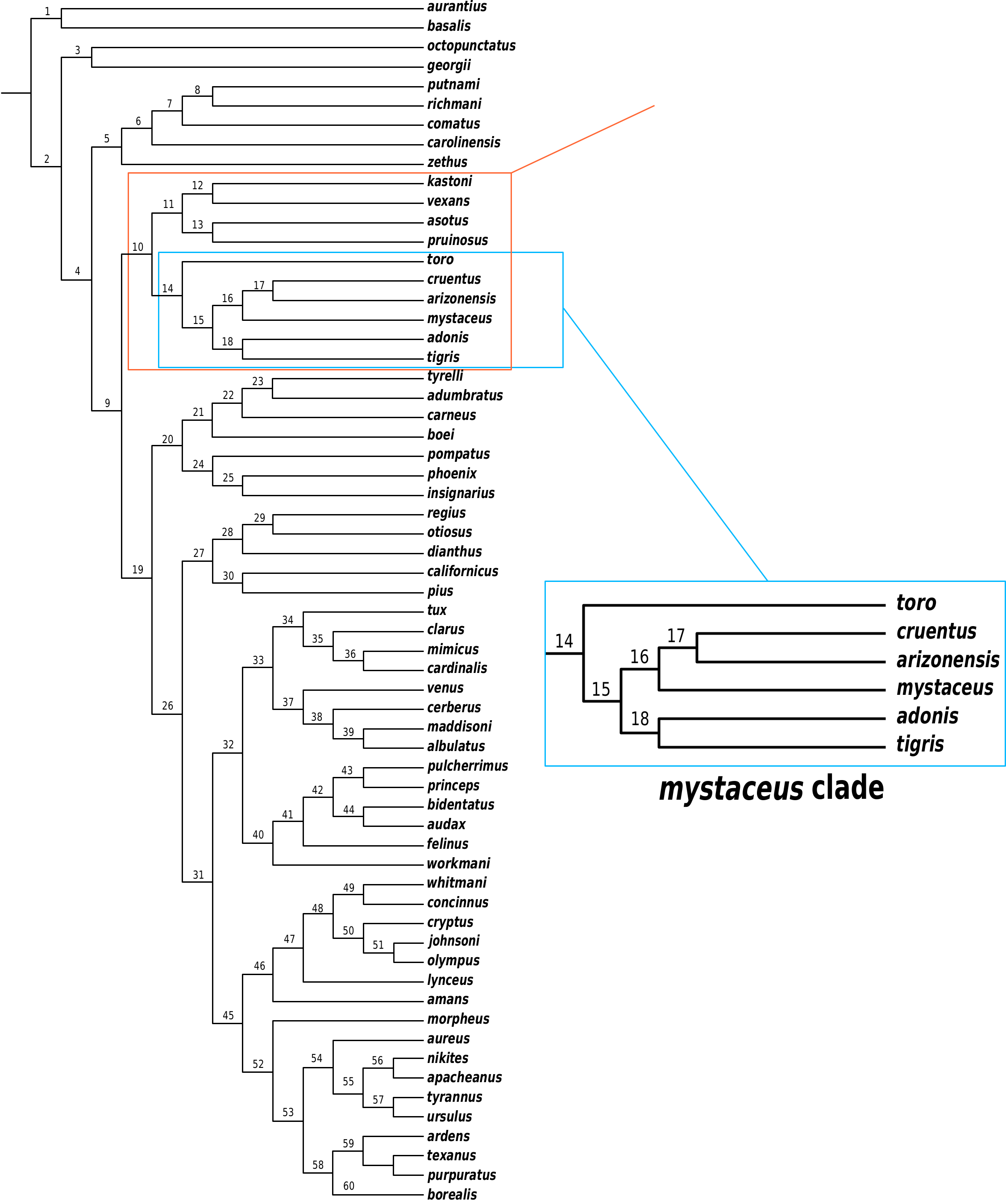

Notes on Relationships. Edwards (2004) defined the mystaceus group as having two subgroups (asotus clade, and toro clade – now mystaceus clade); the mystaceus clade ( Figure 44 View Figure 44 ; Table 1) included six species: P. arizonensis , P. cruentus , and P. mystaceus , all of which have males with yellow leg I decorations ( Figures 24, 27-28 View Figures 24-29 , 31 View Figures 30-33 , 34 View Figures 34-37 ), and P. adonis , P. toro , and P. tigris Edwards, 2004 , all of which have males with entirely or mostly white leg I decorations ( Figures 25, 29-30, 32-33 View Figures 24-29 View Figures 30-33 , 35, 37 View Figures 34-37 ). In addition, all these species except P. tigris have some type of integumental modification to the anterior carapace. Phidippus mystaceus (more prominently in its rare Florida morph) and P. toro have a raised transverse dorsal ridge anterior to the posterior lateral eyes between prominent dorsal setal tufts (along with, respectively, red or pinkish orange (‘coral’) scales on the ridge; Figures 34-35 View Figures 34-37 ). Phidippus adonis , P. arizonensis , and P. cruentus have a broadly expanded anterolateral ‘cheek’ area. Phidippus pacosauritus has a convex narrow lateral extension (‘ear’) where the dorsal edge of the ‘cheek’ area would be in the latter three species, and also in a position lateral to where the transverse ridge exists in the former two species. This suggests that there is a common ancestor that is responsible for the initial and ultimately three types of integumental variations, as no integumental carapace modifications occur anywhere else in the genus.

This also suggests some changes should be made in the species order of this clade, and suggests a possible placement for P. pacosauritus . The first change would be to move P. tigris to the basal position, since it does not have carapace integumental modifications (It does have a unique complex color pattern on the carapace; Figure 30 View Figures 30-33 ). Both P. tigris and P. adonis have alternating black and white circumferential banding on the leg segments, although the fringes are mostly white, especially in P. tigris ( Figure 30 View Figures 30-33 ). In the case of P. adonis , it has carapace ‘cheeks,’ but other characters suggest it is not a direct sister species to the two other species with ‘cheeks,’ P. arizonensis and P. cruentus . It is possible that P. tigris and P. adonis are sister species, as originally proposed by Edwards (2004), in that they both have red on the face, a short, wide fused second spot pair, and broad dorsoprolateral bands on femur I made up of white scales. Phidippus toro fits well in the middle part of the clade, with entirely white fringes on the legs (like P. pacosauritus ), except for the fact that it has an integumental carapace ridge like P. mystaceus , which in one phylogenetic hypothesis would be several branches further up the clade.

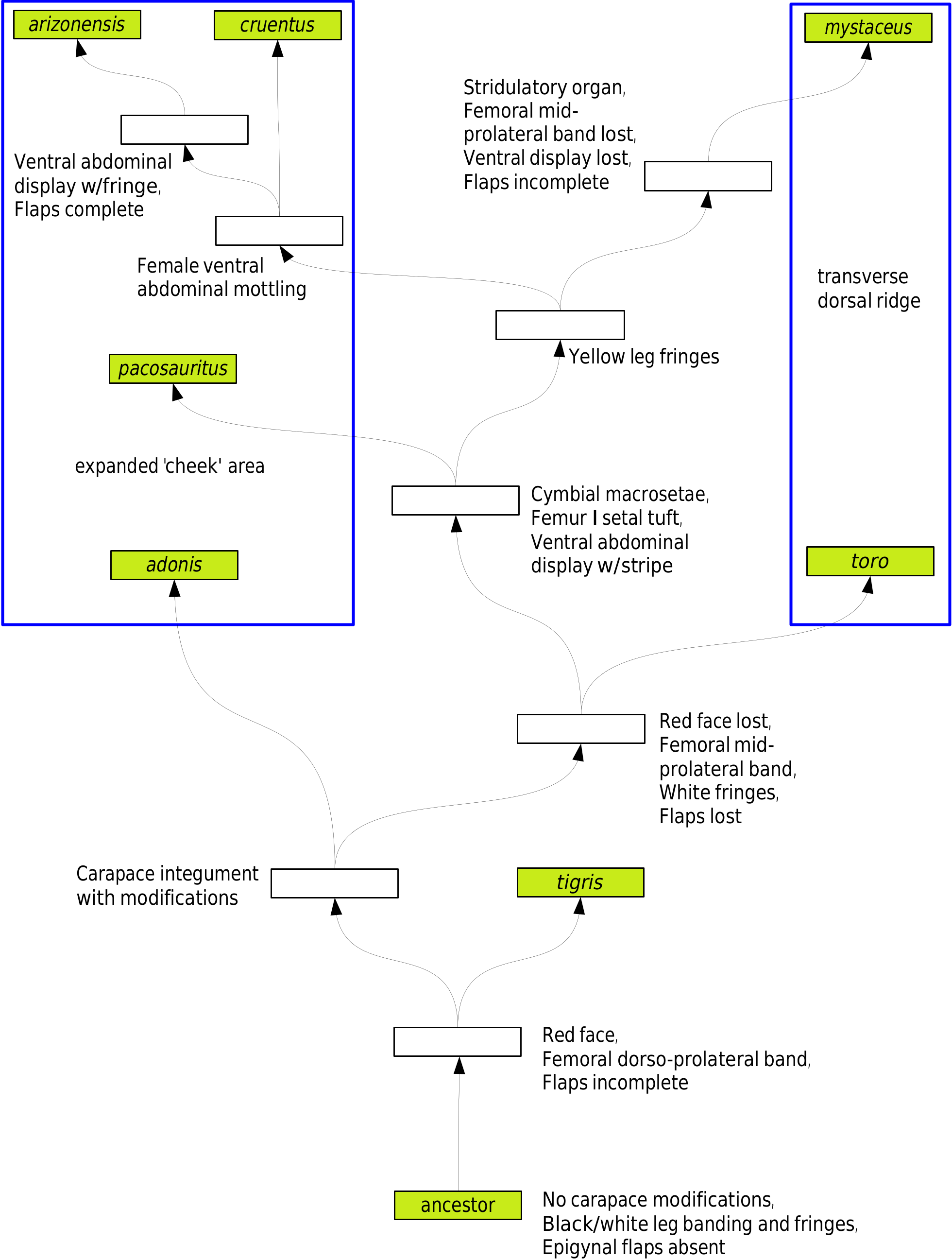

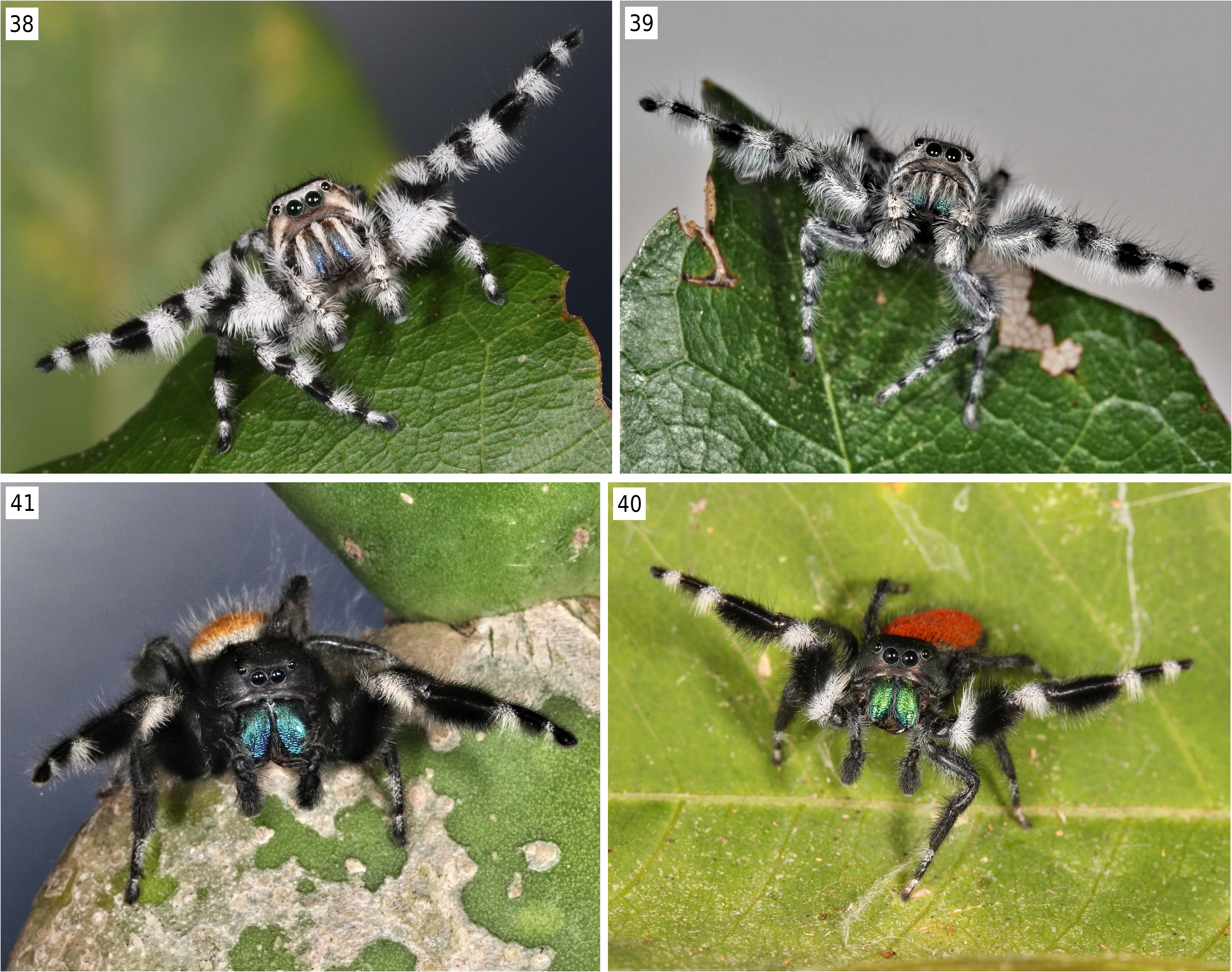

If we assume that the three species with yellow forelegs in the male ( P. arizonensis , P. cruentus , and P. mystaceus ) are each other’s closest relatives, then the logical placement of P. pacosauritus would be immediately basal to the yellow-legged clade ( Figure 45 View Figure 45 ), as here it would continue with the entirely white leg fringes previously introduced with P. toro . Also this would correspond to the synapomorphic unique elements of its courtship behavior to the three species of the yellow legged clade, and the morphological synapomorphies of the four species having a femur I dorsal black setal tuft and distal cymbial macrosetae involved in percussive sound production during courtship (See Notes on Courtship Behavior below for a brief summary). This placement would not require a reversal to white legs if, e.g., P. pacosauritus was thought to be sister to P. cruentus , which has the most similar courtship behavior. Instead, it suggests that P. pacosauritus is sister to the three species of the yellow legged clade, and the shared courtship similarities are ancestral for the four species; this would make sense as both P. arizonensis and P. mystaceus have autapomorphic variations in their courtship behavior and morphology. It is also noteworthy that completely yellow leg fringes are absent in the rest of the genus, and completely white leg fringes are extremely rare outside this clade. For the most part, other species groups have multiple alternations between black and white fringes on each foreleg ( Figures 38-41 View Figures 38-41 ).

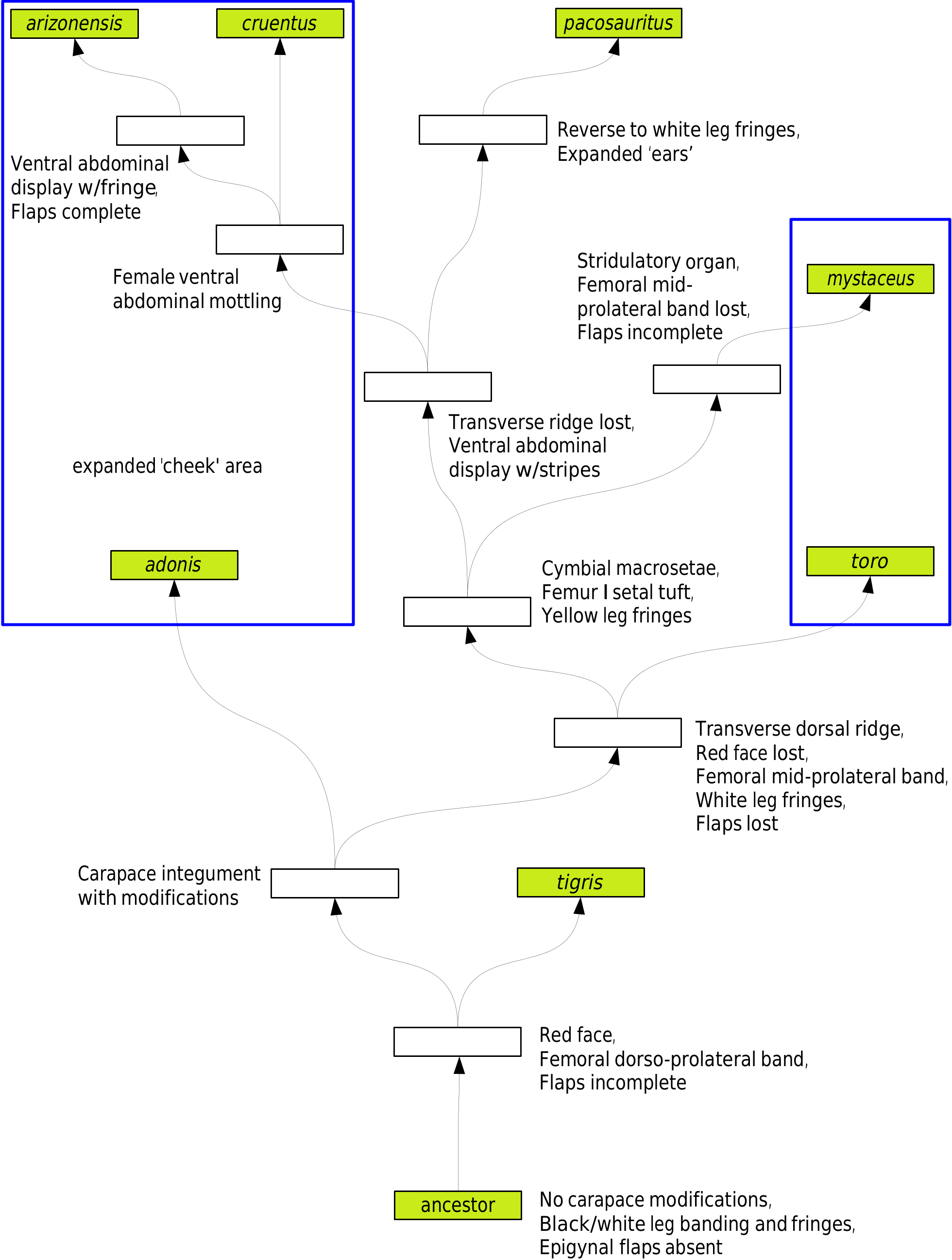

However, what if we rearrange the species to eliminate behavioral and associated morphological homoplasy in P. arizonensis , P. cruentus , P. mystaceus , and P. pacosauritus ( Figure 46 View Figure 46 )? By doing so, we also eliminate some of the other morphological homoplasy (the species with a transverse dorsal ridge are now in sequence), and no longer require P. mystaceus to have lost a ventral display. There is still homoplasy with the species having fully expanded ‘cheeks,’ and P. pacosauritus reverses from yellow to white leg fringes. In this version, P. pacosauritus is sister only to the P. arizonensis - P. cruentus pair, with which it shares the most behavioral synapomorphies. Overall, this version seems more likely as it resolves more problems than it creates. In either hypothetical phylogeny, it might be considered that the ‘ears’ of P. pacosauritus could be a version of the expanded ‘cheeks.'

Notes on Courtship Behavior. Courtship as discussed here is a set of behaviors that occur after a male and female are aware of each other and is initiated by the male. It does not include behaviors that lead to mounting and copulation; i.e., I am only discussing the behaviors that get the male close enough to attempt touching the female. There are two primary positions in Phidippus courtship: a back-and-forth lateral movement phase where the abdomen trails laterally behind, and a stationary phase where the abdomen points directly away from the female, or at least begins to transition to the other side as the male changes direction. The lateral movement phase is typical of many species, and, after some initial leg waving to get a female’s attention, probably serves to initiate courtship. The changes of direction could possibly disorient the female from making an immediate predatory attempt on the male, while also allowing him to edge forward toward her in a circumspect manner. The stationary phase is typically where the male ‘does his thing,’ i.e., where he performs species specific movements of the forelegs and palps intended to properly identify him to the female. This phase can occur quickly as the male transitions to a different direction, or it can be a prolonged affair while the male goes through a more complex repertoire, and is species dependent. It is clear that if willing to mate, females can be very attentive at this stage, and potentially deadly if the male does not perform as she expects (e.g, in the case of a wrong species), or he is distracted and not paying attention to her, even for a moment. Interestingly, the amount of aggressiveness of one sex toward the other varies quite a bit from species to species (David Hill, personal communication, 2020).

The four species with cymbial macrosetae share certain features of their courtship behavior. While P. mystaceus does have an abbreviated lateral movement stage, it spends most of its time in the stationary phase where it repeatedly drums its palps on the substrate, at the same time activating a stridulatory mechanism on the lateral side of each palp ( Edwards 1981). Its forelegs are lowered toward the female with the distal segments turned upward and periodically flicked slightly. The three other species, P. arizonensis , P. cruentus , and P. pacosauritus , all have a similar stationary position: lowered forelegs with upturned distal segments, and palps drumming with audible percussion on the substrate ( Figure 42 View Figures 42-43 ). However, all three species have modified the lateral movement into a display by turning the abdomen laterally in a more raised position and twisting it so that the venter is facing the female. Depending on the species, a black fringe ( P. arizonensis ) or contrasting stripes are presented forward, visible to the female ( Figure 43 View Figures 42-43 ). The abdominal display phase and the stationary percussive phase are alternated several times, with the abdomen switching from one side to the other as the male works his way toward the female. Detailed descriptions of all these courtships are in preparation (Hill & Edwards).

fringe color reversal. Homoplasious carapace modifications in blue.

blue) resolved.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |