Sapajus nigritus (Goldfuss, 1809)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628241 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B72C-285E-0806-FE6C38E5F354 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Sapajus nigritus |

| status |

|

Black-horned Capuchin

French: Sapajou noir / German: Schwarzer Kapuzineraffe / Spanish: Capuchino negro

Other common names: Black Capuchin, Crested Black Capuchin, Horned Capuchin

Taxonomy. Cercopithecus nigritus Goldfuss, 1809 ,

Serra dos Orgaos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

C. P. Groves in 2001 recognized the southernmost (darkest) populations of S. nigritus as a separate subspecies, Cebus nigritus cucullatus, named by Spix in 1823. Its geographic distribution is poorly known, but it is probably a distinct taxon. Monotypic.

Distribution. NE Argentina (Misiones Province) and SE Brazil, S of the Rio Doce and the Rio Grande (E bank affluent of the Rio Parana) in the states of Minas Gerais and Espirito Santo, extending S through the Atlantic Forest, E of the Rio Parana into the N part of Rio Grande do Sul State, to ¢.29° 50° S. The most S occurring of all capuchins. View Figure

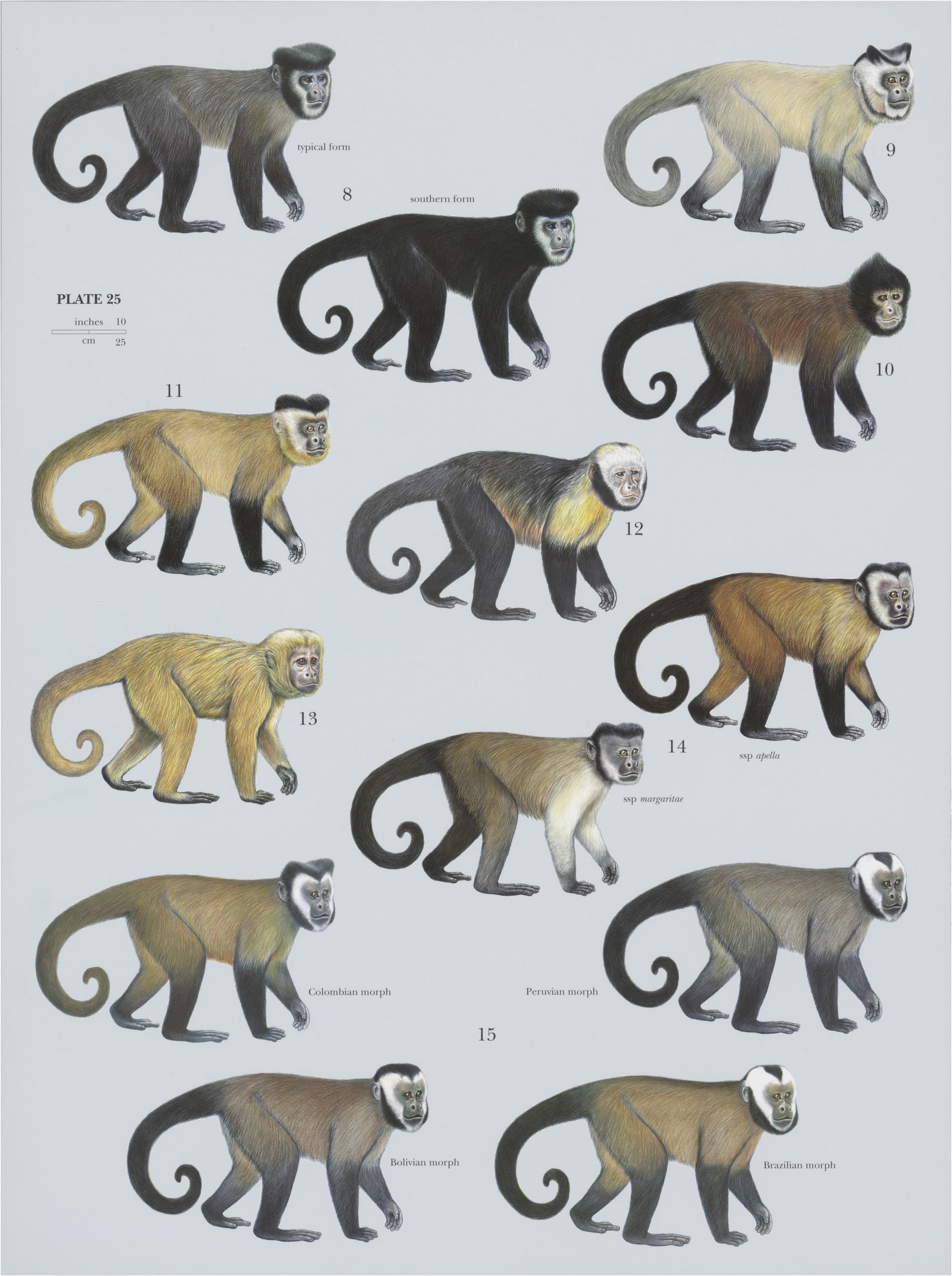

Descriptive notes. Head-body 42-56 cm (males) and 42-48 cm (females), tail 43— 56 cm (males); weight 2-6—4-8 kg. The Black-horned Capuchin is a large species, characterized by horn-like tufts of fur on either side of the head at the temples. It is a very dark brown or grayish to black in the most southerly populations, often with reddish or yellow-fawn underparts. A dark crown contrasts greatly with the light colored face, and crown tufts are well developed in adults. The tail is black.

Habitat. Lowland, submontane, montane tropical, subtropical forest, gallery, and secondary forest. The Black-horned Capuchin was studied by M. Di Bitetti and colleagues in the humid subtropical forest of Iguazu National Park, Argentina, where annual rainfall is 1900-2100 mm but with no marked seasonality. Abundances of fruits and insects are seasonal, however, following day length and temperature—lowest in the winter months ofJune-August and highest in October—January. In Iguazu, Blackhorned Capuchins are found in secondary forests and tall forest with abundant rosewood ( Aspidosperma polyneuron, Apocynaceae ) and palms ( Euterpe edulis, Arecaceae ). P. Izar and colleagues studied two groups in submontane and montane semi-deciduous forests of Carlos Botelho State Park in Sao Paulo State, Brazil, and studies of their ecology, demography, and reproduction were conducted by J. W. Lynch and J. Rimoli in a seasonal, semi-deciduous forest patch of ¢.1000 ha at Caratinga Biological Station in Minas Gerais State, Brazil.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Black-horned Capuchin contains fruits, seeds, leaves, roots, and animal prey (including insects and small vertebrates). In Iguazu National Park, fruits and arthropods are scarce in winter (May-August), and key food sources at this time include palm fruits Syagrus (= Arecastrum) romanzoffiana, important when other fruits are scarce in February—June, figs ( Ficus , Moraceae ), fruits of the vine Pereskia aculeata ( Cactaceae ), shoots of the bamboo Chusquea ramosissima ( Poaceae ), meristems and leaf bases of epiphytes such as orchids, bromeliads, and Philodendron (Araceae) , and cultivated trees including Citrus and the oriental raisin tree Hovenia dulcis ( Rhamnaceae ). They pick tangerines and put their heads up and back, squeezing the fruit to drink the juice. At Carlos Botelho State Park, principal items in the diet are fruit (average 35%), invertebrate prey (22%), and leaves, especially leaf bases of bromeliads and pith of palm leaf stems (rachis) (36%). Leaves dominate diets in the dry season in the northern part ofits distribution.

Breeding. Although mating of the Black-horned Capuchin occurs throughout the year (even when they are pregnant and lactating), births occur only in the early and mid-wet season (October-February) when fruit and insect availabilities are at their highest. Females have fertile ovulatory cycles only during a short period in the early dry season when there is an increase in the number of adult females showing proceptive sexual behavior. Females begin cycling in February-March, and few females are still cycling by August. Conception usually occurs after 2-5 ovarian cycles in late autumn or winter when food availability is lowest and day length shortest. At this time, testosterone levels of alpha and subordinate males increase, although there is generally no overt competition among them for the females’ attentions. Adult males are not aggressive toward females as they are in species of Cebus . Female Black-horned Capuchins solicit mating, usually from the alpha male, with an elaborate courtship. The female’s proceptive phase lasts c.4-6 days at intervals of 14-21 days, probably reflecting the ovarian cycle. Her consortship with an alpha male lasts c.3—4 days. Adult females show a preference for the alpha male; they follow him constantly and consort with subordinate males only when he is engaged with another female. Female Black-horned Capuchins never solicit subadult males. During this consortship, the alpha male is slow to respond and delays copulating for hours or even days. He delays more in the dry season when females are fertile than in the wet season when they are not. After he mates, there is a post-copulatory phase, which is believed to be a form of mate-guarding on the part of the male; he follows the female rather than vice versa. The female ovulates on the sixth or last day of her proceptive phase, and she also mates with subordinate males at this time. When females solicit subordinate males, the courtship is less complex, the response by the male is more immediate, the male and female separate immediately, and there is no post-copulatory consortship. These are referred to as “unimount” copulations. Alpha males are never interrupted by subordinate males, and subordinates are only occasionally interrupted by alpha males. Males evidently do not mate twice in the same day. The reason behind the reluctance of the alpha male to mate is believed to be because they are unable to ejaculate more than once a day, and for this reason, a premium is placed on making sure that each mating counts. Although the alpha male is apparently reticent and choosy, he eventually copulates with all, or nearly all, females in the group in any one mating season, and genetic studies have shown that the alpha male generally sires all offspring in the group. Gestation is ¢.153 days (range 149-158 days). Interbirth intervals at Caratinga Biological Station average 25-6 months (range 21-35 months), which is shortened to eleven months (range 9-14 months) when an infant dies. At Iguazu National Park, the estimated birth rate is 0-6 infants/female/year, with a mean interbirth interval of c.19 months, although some females breed successfully in successive years. When infants die before they are six months old, the interbirth interval is shortened to 11-12 months. The interbirth interval recorded at Carlos Botelho State Park is longer, averaging 30 months (n = ten females). Infants are weaned at 12-18 months. Females reach puberty (begin ovarian cycling) at about four years old, but they first conceive only when they are more than 4-5 years old, giving birth when they are generally 6-7 years old. Females begin cycling in February—March, and few females are still cycling by August. Conception usually occurs after 2-5 ovarian cycles in late autumn or winter when food availability is lowest and day length shortest.

Activity patterns. Activity budgets of Black-horned Capuchins differ somewhat according to season and whether groups travel together or divide into subgroups. When traveling together in the wet season (food abundant), the day is divided into eating ¢.22% of the time, handling food c.14%, searching (stationary) for food ¢.8%, traveling ¢.39%, resting c¢.6%, social activities ¢.6%, and miscellaneous ¢.5%. In the wet season, individuals in subgroups spend more time eating, less time handling and more time searching for food,less time traveling and resting, and more time in social activities. The same comparison of subgroups in the dry season also found them eating, handling, and searching for food more, while traveling, resting, and socializing less. Overall, foraging (eating, handling, and searching for food) takes up ¢.38-44% of their day. In Carlos Botelho State Park, foraging consumed more time, averaging c.58% oftheir day, with traveling averaging 36%; very little time was spent resting and socializing (average 6%). In Iguaza National Park, one group used 34 sleeping sites during 203 nights, five of which were used more than 20 times each. All sites were tall (average height 31 m), large-crowned (average diameter 14 m) trees with numerous horizontal branches and forks.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Groups of 8-35 Black-horned Capuchins have been recorded at Iguazu National Park (averaging 12-17 individuals depending on the year), occupying home ranges of 81-293 ha (average 161 ha). Home ranges of two groups of eight individuals and 19 individuals in the Carlos Botelho State Park averaged 484 ha. Groups at other locations in the state of Sao Paulo had 8-15 individuals with 1-2 adult males. A group studied at Caratinga Biological Station was relatively large, with 24-28 individuals including four adult males, two subadult males, six adult females, six subadult females, and juveniles and infants. This group tended to divide into subgroups, which, when comparing activity budgets with single cohesive groups, evidently provides a slight but probably significant advantage when looking for food. At Carlos Botelho, groups divide into subgroups when food patches are smaller. At Iguaza, male Black-horned Capuchins disperse from their natal groups at 5-9 years old, but females are philopatric. Females may also transfer groups especially when groups divide or there is a change of the alpha male. Males and females form hierarchies, and although there is often more than one adult male in the social group, females interact and associate more with the alpha male than with subordinate males and other females. The alpha male sires most or all infants born in the group. His tenure can exceed eight years, but young adult females in the group avoid soliciting their father. Infanticide has been recorded when a new male takes over the alpha position in the group. On these occasions, pregnant females mate with the incoming male—probably a strategy to avoid infanticide.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List (as Cebus nigritus ). The Black-horned Capuchin is adaptable and widespread, but the large majority of its original forests have been destroyed and fragmented. It is hunted for food. It occurs in a number of protected areas, including Iguazu National Park in Argentina, and Caparao and Iguacu national parks, Carlos Botelho, Intervales, Alto Ribeira, Morro do Diabo, Rio Doce and Serra do Brigadeiro state parks, and Xitué State Ecological Station in Brazil.

Bibliography. Carosi et al. (1999), Di Bitetti (2001, 2003a), Di Bitetti & Janson (2000, 2001), Di Bitetti et al. (2000), Fragaszy, Fedigan & Visalberghi (2004), Fragaszy, Visalberghi et al. (2004), Freese & Oppenheimer (1981), Groves (2001), Izar, Verderane et al. (2012), Izar, Ramos-da-Silva et al. (2007), Lynch Alfaro (2005, 2007), Lynch & Rimoli (2000), Ramirez-Llorens et al. (2008), Rylands, da Fonseca et al. (1996), Rylands, Kierulff & Mittermeier (2005), Torres (1988), Wright & Bush (1977).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.