Indri indri (Gmelin, 1788)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6709103 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6708882 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5D328790-5C49-FFF1-AECD-F74080DBFA37 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Indri indri |

| status |

|

19. View On

Indri

French: Indri / German: Indri / Spanish: Indri

Other common names: Babakoto

Taxonomy. Lemur indri Gmelin, 1788 View in CoL ,

Madagascar.

There appears to be a regional trend regarding the amount of white and black fur on thecoat, and as a consequence, two distinct subspecies were formerly recognized. This 1s now believed to constitute a cline, with darker individuals in the north of the distribution andlighter ones in the south. Monotypic.

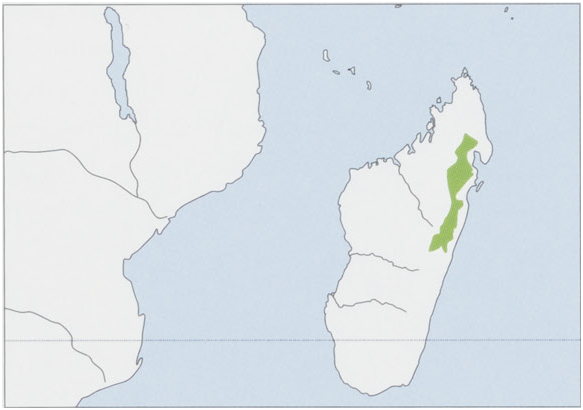

Distribution. NE & CE Madagascar, found roughly from the Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve in the N to the Anosibe an’ala Classified Forest in the S. View Figure

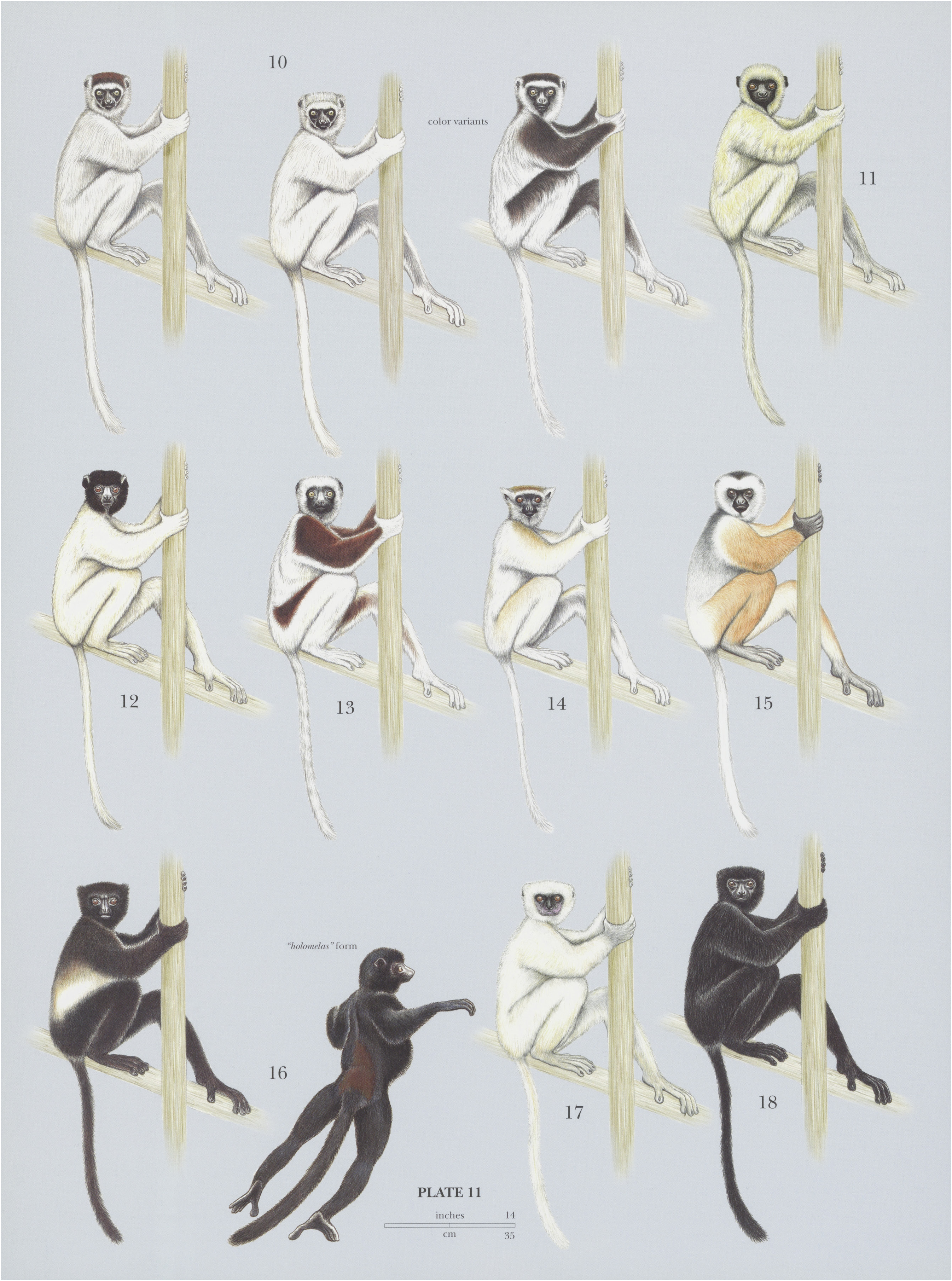

Descriptive notes. Head—body 64-72 cm, tail ¢.5 cm; weight 5.8-9 kg. The Indri is the largest living lemur, with only the DiademedSifaka ( Propithecus diadema ) approaching it in size. The Indri’s bodyis thickly covered with long,silky fur above, which becomes shorter underneath, and the skin is black. The head is rounded with a prominent, nearly naked muzzle, large ears, andrelativelylargestaring eyes that are directed more forward than laterally. Irises are yellow-brown, with circular pupils, and are accentuated by long eyelashes. Coat colorvaries considerably by region from predominantly black, contrasting with white or grayish-white patches on the crown, neck, flanks, forelimbs, and thighs (or any combination ofthese) to variegated black and white; the whiteareas correspondto the occipital cap, a broad collar extending up to and beyond the ears, and the outer surfaces of legs and lower arms. In some populations, heels and flanks maybetinged with red or gold. The northern form is predominantly black. The earliest Indris to be described had this darker color pattern, which is typical of museum specimens from Andapa and Maroantsetra and has also been observed In wild populations from Anjanaharibe-Sud, Ambatovaky, and Anjozorobe. Indris from central-eastern Madagascar are generally lighter in color. Further complicating the color variation among Indris , both melanistic and albino individuals havealso beenrecorded. Theclassic pattern of the Giant Panda (Auluropoda melanoleuca) appears to be less common among populations of Indris than the largely or entirely black pattern. Thereis also someslight dimorphism in color pattern, with the chest of the male dark and that ofthe female much lighter. The male also has a white triangle at the base of its back, but this marking is absent in the female. Whether these differences hold true in other parts ofthe distribution of the Indri remains to be determined. Regardless of coat color or pattern, however, ears are always black, modestlytufted, and prominent.

Habitat. Primary and secondarytropical moist lowland and montane forest, also some disturbed habitats. Theelevational range ofthe Indriis sea level to 1800 m. Theyare often found in mountainous habitats or steep terrain with numerous ridges and valleys. All levels ofthe canopyare used, although individuals tend to stay in the lower levels in October-Decemberto avoid biting insects.

Food and Feeding. Indris feed mainly on immatureleaves, althoughfruits, seeds, flowers, buds, and bark are also eaten; bark consumption varies seasonally. Individuals also descendto the groundto eat soil, which may help to detoxify seeds or perhaps facilitate the breakdownof their bulkydiet.

Breeding. Reproduction ofthe Indri is highly seasonal. Mating takes place in December—March andis performed ventro/ventrally while hanging beneath a branch. Only one pair of adults in a group produces offspring. The female produces a single young about every 2-3 years—a veryslow reproductive rate for a prosimian. Births usually occur in May-June (but can be as late as August), and gestation is 130-150 days. Indri young tend to be entirely black during thefirst 2-3 months oflife, with white only on a small patch in the pygal region; they develop the characteristic gray and white patches of adults at 4-6 months of age. The mothercarries heroffspring across her abdomen for thefirst 4-5 months and then on her back. Young are reasonably independent at 8-10 months, but theystay close to the mother until well into their second year. They reach maturity at about fouryears of age, although females do not reach full sexual maturity until 7-9 years. Longevity is unknown.

Activity patterns. TheIndri is diurnal and arboreal. Its signature vocalization is a loud, drawn out, wailing territorial call that is one of the best known and most characteristic sounds of the Malagasy rainforest. Territorial calls have been described as a plaintive bark, blending with lamenting cries that soundlike a mixture of a human crying in pain and howling ofa frightened dog. This call is heard most often during the morning hours but can be heard at anytimeof the day;it can carry across the forest for up to 2 km. It is also more frequently given in the warm rainy season than in colder months. The adult pair in a family social group typically leads the chorus, and neighboring groups often call sequentially in response. Spacing among groupsis likely determined by these calls, which may explain the relatively small degree of home range overlap.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Indri has been studied in the forests of Analamazaotra Special Reserve and nearby Mantadia National Park. It lives in small groups of 2-6 individuals, normally consisting of a monogamous adult pair (they evidently seek new partners only after a mate dies) and their offspring. Although groups in fragmented habitat tend to be larger than those in more extensive, undisturbed areas, this is not always the case. Changes in the composition of larger groups are quite frequent. Home range size averages 18 ha in the fragmented forests of Analamazaotra, but it can be as large as 40 ha in the more pristine forests of Mantadia, where daily movements are 300-800 m. A large central part of each home rangeis defended, from which other groups are excluded. Individuals are extremely attached to their home range, and they always use the same trails within it. Adult males are responsible for territorial defense; the female movesto a safe location during encounters with intruders. There also is frequent agitation in the group and competition for food, and females and young are dominant in such situations, easily displacing an adult male. A female normally feeds higher in the trees than a male and has priority access to food resources. Before dusk, the group retires to a sleeping tree, bedding down on horizontal supports at heights of 10-30 m; the female is typically huddled with her offspring and separated from the male by 2-50 m. Reciprocal grooming has been reported, but not simultaneously. Densities typically are 9-16 ind/km? but are as low as 5-2 ind/km? in some areas. Indris can reach relatively high densities (c.22-9 ind/km?) if they are not hunted by local people.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. However, at the IUCN/SSC Lemur Red-Listing Workshop held in July 2012, I. indri was assessed as critically endangered. The principal threat to the Indri is habitat destruction for slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, and firewood gathering, affecting even protected areas. Contrary to what was believed in the past,illegal hunting ofthe Indri is also a major problem in certain areas. Although long thought to be protected by local “fady” (taboos), these do not appear to be universal, and Indris are now hunted even in places where such tribal taboos exist. In many areas, these taboos are breaking down with cultural erosion and immigration, and local people often find ways to circumvent taboos even if they are still in place. For example, a person forbidden to eat Indris can still hunt and sell them to others, and those forbidden to kill Indris can purchase them for food from someone else. Recent studies of villages in the Makira Forest indicate that Indris have been hunted in the past for their skins (worn as clothing), Indri meatis prized and fetches a premium price, and current levels of hunting are unsustainable. The Indri occurs in three national parks (Mananara-Nord, Mantadia, and Zahamena), two strict nature reserves (Betampona and Zahamena), and five special reserves (Ambatovaky, Analamazaotra, Anjanaharibe-Sud, Mangerivola, and Marotandrano). It also is found in the forests of Anjozorobe-Angavo and Makira, which are currently under temporary government protection (although hunting pressure appears to be especially heavy at Makira). The corridor between Mantadia and Zahamena has been proposed as a new conservation site, and the Anosibe an’ala Classified Forest also should be considered for the creation of a new park or reserve. No population figures are available for the Indri , but a reasonable estimate would be 1000-10,000 individuals. The Indri does not occur on the Masoala Peninsula or in Marojejy National Park, despite the park being connected to forest less than 40 km away where the Indri occurs. Before large-scale deforestation, it was much more widely distributed, with a separate group said to occupy almost every ridge of Madagsacar’s eastern forests. Subfossil evidence indicates that they once occurred well into the interior of Madagascar at least as far west as the Itasy Massif, south-west to Ampoza-Ankazoabo, and north to the Ankarana Massif.

Bibliography. Britt, Axel & Young (1999), Britt, Randriamandratonirina et al. (2002), Garbutt (2007), Geissmann & Mutschler (2006), Glessner & Britt (2005), Godfrey et al. (1999), Golden (2005), Goodman & Ganzhorn (20044a, 2004b), Groves (2001), Jungers et al. (1995), Mittermeier et al. (2010), Nicoll & Langrand (1989), Oliver & O'Connor (1980), Petter (1962), Petter & Peyrieras (1972, 1974), Petter et al. (1977), Pollock (1975a, 1975b, 1977, 1979a, 1979b,1986a, 1986b), Powzyk (1997), Powzyk & Mowry (2003, 2006), Powzyk & Thalmann (2003), Rand (1935), Rigamonti et al. (2005), Schmid & Smolker (1998), Tattersall (1982, 1986b), Thalmann et al. (1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.