Rhinoceros sondaicus, Desmarest, 1822

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720730 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720748 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5E3FD96D-FFEA-721D-493E-F4A8FE6070D9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Rhinoceros sondaicus |

| status |

|

4. View Figure

Javan Rhinoceros

Rhinoceros sondaicus View in CoL

French: Rhinocéros de Java / German: Java-Nashorn / Spanish: Rinoceronte de Java

Other common names: Lesser One-horned Rhinoceros

Taxonomy. Rhinoceros sondaicus Desmarest, 1822 View in CoL ,

Java, Indonesia.

Three subspecies are recognized historically, but race inermis (Lesson, 1838) from India and Bangladesh is extinct. Two extant subspecies currently recognized.

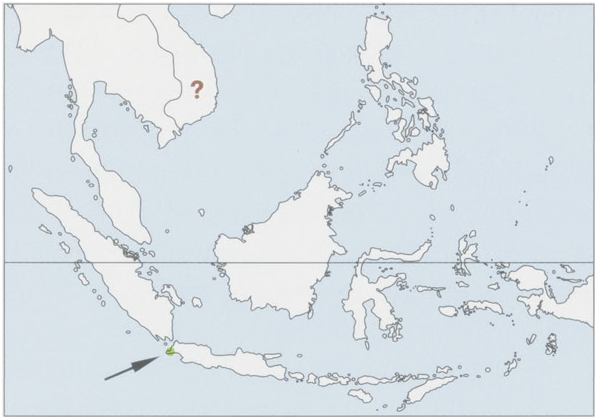

Subspecies and Distribution.

R.s.sondaicusDesmarest,1822—WJava.

R. s. anamiticus Heude, 1892 — Vietnam (now close to extinction). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 305-344 cm, no reliable data available on tail length, shoulder height 150-170 cm; weight 1200-1500 kg. Few data exist on body mass of wild individuals. In many ways, the Javan Rhino is a smaller version of the Greater Onehorned Rhinoceros ( R. unicornis ). Single, nasal horn; length of horn averages 25 cm in males, but unlike in the Greater One-horned Rhino, female Javan Rhinos typically lack horns. Skin folds are noticeable, as in Greater One-horned Rhinos, but adult males lack the pronounced “bib” of the former species. Hair is limited to fringes of ears, eyelashes, and tail tip. Body color is gray and mosaic-like pattern on skin is quite noticeable on rump. Pedal scent glands present.

Habitat. The Javan Rhino is found in lowland semi-evergreen forest in its last refuge on Java and in rattan-dominated scrub in its last outpost in Vietnam. Previous records showed that Javan Rhinos are good climbers and ascended into montane forests to feed. They also occupied similar alluvial flood plain habitats as Greater One-horned Rhinos. Of some concern in Ujung Kulon,Java, is that the forest has become too mature to provide enough forage for the remaining population. The eruption of the Krakatau Volcano in 1883, and the subsequent tsunami, likely had a profound effect on Javan Rhino habitat.

Food and Feeding. Recent field studies of diet are lacking. Historical accounts, based on feeding signs, show thatJavan Rhinos eat mostly browse. However, their occupation of alluvial flood plains suggests that grasses were a much larger part of the diet in such habitats. Browse species in Ujung Kulon include more than 100 plants, but no quantitative data on rhino diets are available. In Vietnam, some of the plants browsed include the climbing Acacia (A. pennata—also eaten by the Greater One-horned Rhino), two species of rattan (Calamus), two Bambusoid grasses (Bambusia), a tree fern (Cyathea), and Strychnos nux-vomica. Javan Rhinos, given their size and browsing behavior, might be expected to have a major impact on seedling and sapling recruitment of woody plants when at normal densities. The Javan Rhino’s congener, the Greater One-horned Rhino, exerts strong selective pressure on forest structure and canopy composition by inhibiting vertical growth of saplings, by frequent browsing and trampling.

Breeding. Virtually nothing is known about the breeding biology in this species. A few observations indicate that, as in Greater One-horned Rhinos, males engage in courtship chases with females that can last for several hundred meters and be accompanied by loud vocalizations. No data exist on gestation, season of parturition, age at first reproduction, or other critical reproductive features.

Activity patterns. In Vietnam, the remaining population was thought to be largely nocturnal. Perhaps this behavior is as much due to the threat of poachers as a preference for nocturnal feeding. Javan Rhinos may be too large to feed only at night, as they may need more food to meet their nutritional demands than they can eat during the night, even though daytime foraging might put them at risk. Their congener, the Greater One-horned Rhino, feeds both day and night. The heat and humidity of the Javan site suggests that rhinos must spend a considerable amount of time in wallows. Early accounts frequently mentioned the importance of wallows in the landscape. When wallows dry up, Javan Rhinos may use tidal forests and muddy banks to reduce heat stress.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Little is known about movements and spacing in this species except from historical records. Rhinos are so few in number today that they can be widely spaced. Accounts from the mid-1700s in Java describe bounties on Javan Rhinos to reduce crop depredation. The large numbers shot in small areas suggest that, even if this species was mostly solitary, it lived in high densities; home ranges were likely small, on average the size of those observed in Greater One-horned Rhinos.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Formerly India, Bangladesh, south-western China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, and Java. Now restricted to two sites, and the last Javan Rhino in Cat Loc, Vietnam, may have been poached in 2010. This species is widely considered to be the most endangered mammal on earth. The tragic decline in the Javan Rhino is one of the most unfortunate conservation stories of our time. In the 1980s, when it became clear that the Ujung Kulon population had plateaued at around 50 individuals, several efforts were made to promote translocation to another site in Indonesia. Captive breeding specialists from western countries discouraged such efforts even though they have been highly successful in repopulating the range of other rhino species, including the Greater One-horned Rhino. Today, translocation plans are underway and it is hoped that a second population will be reestablished in a reserve on Java. Prior to the Vietham War, or certainly the French Indochina war, there may have been more Javan Rhinos in Indochina than in Java. No western biologist had the opportunity to study this area at the time. The rhino population in Vietnam survived the hostilities, but has dwindled rapidly over the past two decades. However, the opportunity to bolster this population is complicated because there are no animals in captivity, and the Ujung Kulon population is a differ ent subspecies. Such rescue efforts may be moot, given that a recent survey using scent dogs to find rhino droppings failed to turn up any samples, and a poached rhino was found with, a bullet lodged in its leg. Despite the nearby Cat Tien National Park, this small population remained in a scrub jungle (Cat Loc) lacking a corridor to connect with Cat Tien. The Vietnam population now appears doomed, but there is still hope for the Ujung Kulon population if translocation efforts go forward. The rapid increase in small founder populations of Greater One-horned Rhinos translocated to new reserves suggests that rapid growth is possible if poaching is controlled.

Bibliography. Ammann (1985), Barbour & Allen (1932), Burton (1951), Corbet & Hill (1992), Cranbrook et al. (2007), Foose & van Strien (1997), Hariyadi et al. (2010), Hoogerwerf (1970), Khan (1989), Mackinnon & Santiapillai (1991), Polet & Ling (2004), Polet et al. (1999). Prothero & Schoch (1989), Ramano et al. (1993), Sadjudin (1987), Schenkel & Schenkel-Hulliger (1969a, 1969b), Schenkel et al. (1978), van Strien & Rookmaaker (2010), Talukdar et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Rhinoceros sondaicus

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Rhinoceros sondaicus

| Desmarest 1822 |