Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (G.Fischer, 1814)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720730 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720750 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5E3FD96D-FFEB-721E-49E6-FE2BF88F79D6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Dicerorhinus sumatrensis |

| status |

|

5. View Figure

Sumatran Rhinoceros

Dicerorhinus sumatrensis View in CoL

French: Rhinocéros de Sumatra / German: Sumatra-Nashorn / Spanish: Rinoceronte de Sumatra

Other common names: Asiatic Two-horned Rhinoceros, Hairy Rhinoceros

Taxonomy. Rhinoceros sumatrensis Fischer, 1814 View in CoL ,

Sumatra.

Three subspecies recognized.

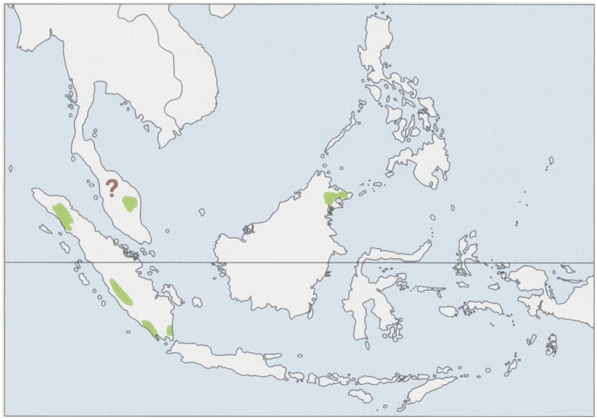

Subspecies and Distribution.

D.s.sumatrensisFischer,1814—SumatraandPeninsularMalaysia.

D.s.harrissoniGroves,1965—Borneo.

D. s. lasiotis Buckland, 1872 — South-east Asia (could be extinct). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 236-318 cm, no reliable data available on tail length, shoulder TT 100-150 cm; weight 600-950 kg. Few data exist on body mass of wild individuals. The Sumatran Rhino is the smallest of the five living rhino species, the most ancient in the lineage, and the most distinct in appearance. This is the only Asian rhinoceros featuring two (small) horns, hairy ear tufts, and a hairy, reddishbrown skin. The relative degree of hairiness of the body varies with age and among individuals, but clearly separates this species from the other four in appearance. Two clear skin folds present on body. Size of horns varies but typically larger in males; often only the nasal horn is conspicuous, the second or frontal horn is much reduced in size. Horn lengths from some museum specimens are large (25-80 cm) but may not be indicative of average size.

Habitat. Sumatran Rhinos seem to be generalists in habitat. They were formerly found from lowland semi-evergreen forests to high-elevation cloud forests. They ascended and descended steep terrain, and still do in Kerinci-Seblat National Park. This species is also an excellent swimmer, even in salt water, so probably reached small islands close to coastlines. The natural history literature provides evidence that bulls often resided on the edge of forests where they abutted villages. Recently, a male Sumatran Rhino in Sabah wandered from the forest edge into a village, where it was captured and placed in a breeding program. Many of the Sumatran Rhinos in semi-captive situations show a preference for food plants typical of second growth forests, light gaps, and disturbed areas. Thus, it is likely that continuous primary forests held lower densities of this species than more heterogeneous forested regions.

Food and Feeding. Prior to captive breeding efforts in the region, information about feeding behavior and diet selection was largely based on signs of browse in forest patches. Much has been learned recently about the diet of the Sumatran Rhino from semi-captive animals in Sabah, Peninsular Malaysia, and Sumatra. This species is mostly a browser, but prefers pioneer and second-growth plants such as Macaranga spp. and other Euphorbiaceae, Ficus , Rubiaceae (Nauclea) , and other saplings and shrubs. Typically, fast-growing trees and treelets of second growth and light gaps are lower in secondary compounds than plants of the primary forest understory, and this factor may also influence diet selection. Like other browsing rhinos, this species will walk over saplings to reach leaves clustered at the tips of branches.

Breeding. Like the Greater One-horned Rhinoceros ( Rhinoceros unicornis ) and other rhinos, Sumatran Rhino males are reported to be aggressive towards females and are known to injure or even kill them during courtship. However, aggressive chasing may be part of the courtship ritual for some rhino species, and without such behavior, copulation or insemination may be unsuccessful. Nevertheless, captive breeding efforts for this species keep males away from females until estrus and do not allow space or opportunity for chasing. Data from zoo populations reveal a gestation period of 15-16 months, an intercalf interval of 3-5 years, and calves remaining with their mother for 2-3 years. Females do not reach sexual maturity until 6-7 years, slower than the larger bodied Greater One-horned Rhino.

Activity patterns. Most records show remaining populations to be largely nocturnal, but this pattern may also be a function of intensive poaching pressure across the range. The heat and humidity in the range of this species suggest that rhinos must spend a considerable amount of time in wallows. Early accounts frequently mention intensive feeding in the morning hours, the importance of wallows in the landscape, and the animals’ presence of up to several hours in a wallow both day and night.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Little is known about movements and spacing in this species except from historical records. Seasonal movements seem to be influenced by the rainy season, with rhinos leaving flooded areas in the lowlands to take to higher ground, and returning when the rains end and standing water disappears. Rhinos frequently visit salt licks. Populations in hilly areas move up and down mountains with no trouble and they are excellent swimmers, so we can assume that Sumatran Rhinos are excellent dispersersif suitable habitat is available. Today, populations are so few in number and so widely spaced, little can be inferred about home range and social organization. The researcher N. van Strien followed tracks of individuals for several kilometers through mountainous terrain. His observations highlighted sapling-twisting behavior in Sumatra. Such marking behavior might serve to delimit the home ranges of adult bulls, but this remains speculation. Sumatran Rhinos in a semi-captive situation in the Danum Valley, Sabah, may shed new light on home range and social organization for a species about which much is anecdotal and where there is no information based on closely marked or radiocollared individuals. Sumatran Rhinos appear to be solitary except for the mothercalf pairing.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Formerly from Assam, India to Vietnam, through Malaysia, and on Sumatra and Borneo. More widely distributed than the Javan Rhinoceros ( R. sondaicus ), but populations very small and isolated. The mainland Asian subspecies, lasiotus, is probably extinct. No recent surveys have turned up signs or local reports of this subspecies. Of the remaining two subspecies, the western Sumatran Rhino, sumatrensis , is the more common. Three disjunct populations exist that seem to be the last strongholds: Taman Negara National Park in Peninsular Malaysia; Bukit Barisan Selatan and Way Kambas National Parks, and Gunung Leuser National Park in Sumatra; and scattered small populations elsewhere totalling not more than 250 individuals. Danum Valley Conservation Area and Tabin Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia, are the last strongholds of the subspecies harrissoni, with less than 50 individuals estimated. It is one of the most threatened large mammals on earth. Until recently, conservationists considered the Sumatran Rhino the most endangered of all five species. Even though the Javan Rhino population in Ujung Kulon National Park, Java, is smaller in total numbers, it has remained stable for decades and poachers have been largely kept at bay. In contrast, Sumatran Rhino populations across the range were crashing due to poaching and habitat loss, declining by about 50% over the past 15 years. The extensive development of oil palm plantations in the heart of the range has converted much valuable rhino habitat and allowed poachers to access formerly remote areas. The most controversial conservation program ofthe last 50 years has centered around Sumatran Rhinos. Zoo biologists argued that many isolated, small Sumatran Rhino populations were doomed because the areas they occupied were slated for conversion to oil palm or pulp and paper production. A better strategy was to bring them into captivity to grow the population, and eventually release offspring into the wild under safer conditions. Results were catastrophic. Of the 40 animals brought into captivity, virtually all died and none bred, an even worse decline than seen in the wild. Successful breeding occurred 20 years later, but only at great cost. Some conservation biologists have argued that captive breeding helped this species go extinct in the wild in many places, with nothing to show for an enormous financial investment (money that would have been better spent on in-situ protection). Protecting remaining populations depends on the effectiveness of Rhino Protection Units to patrol critical habitat and give small populations a chance to rebound. With no more than 275 Sumatran Rhinosleft in the wild and scattered among fragmented populations, there is little time to waste. Other major efforts at semi-captive breeding are underway in Sabah, Malaysia, and in southern Sumatra, yet it seems clear that wild populations breed much faster than captive stock. Greater emphasis on intensive protection in key areas, which has been successful in recovering populations of rhinos elsewhere, should be applied diligently and for an extended period.

Bibliography. Ali & Santapau (1959), Andau (1995), Andersen (1961), Ansell (1947), Burgess (1961), Christison (1945), Crosbie (2010), Evans (1904, 1905), Foose (2003, 2004), Foose & van Strien (1997), Groves (1965, 1967a, 1967b, 1971), Hislop (1966), Kawanishi et al. (2003), Khan et al. (2000), Kretzschmar (2010), Kurt (1971), Meijaard (1996), Metcalfe (1961, 1964), von Muggenthaler et al. (2003), O'Brien & Kinnaird (1996), Rabinowitz (1995), Rabinowitz & Saw Tun Khaing (1998), Roth et al. (2006), Siswomartono et al. (1996), van Strien (1986), Wielandt (2002), Zainuddin et al. (2000).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Dicerorhinus sumatrensis

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Rhinoceros sumatrensis

| Fischer 1814 |