Pecari tajacu, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5720788 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720799 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/6D3587F9-FFC7-FF90-FFB6-122C81888E7F |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Pecari tajacu |

| status |

|

Collared Peccary

French: Pécari a collier / German: Halsbandpekari / Spanish: Pecari de collar

Other common names: Javelina

Taxonomy. Sus tajacu Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

Pernambuco, Brazil; but Thomas erroneously designated the type locality as Mexico in 1911.

The Collared Peccary ancestry seems to have an early divergence from the other peccary lineages in the Americas. P. tajacu has been referred to as both Tayassu tajacu and Dicotyles tajacu . Recent genetic research, however, shows that Collared Peccaries cluster in a separate lineage from the other modern species. This, plus taxonomic complications arising from the use of the latter two genus names, makes the use of P. tajacu most appropriate. Early morphological studies provided evidence of cranial and dental variation among Collared Peccaries from throughout the Americas, although specimens were ultimately grouped into a single species by taxonomists. Recent DNA studies suggest that the geographically widespread and phenotypically diverse Collared Peccary may consist of at least two clades, possibly deserving species status, one in North and Central America and the other in South America. Structural chromosomal differences and possible rearrangements between North and South American specimens have also been observed. DNA also shows Collared Peccaries from Arizona and Texas clustering as separate sister clades, with Mexican specimens split between these two groups. This is consistent with the hypothesis that peccaries in the USA originated from Mexican populations. Given observed morphological, chromosomal, and DNA variation, further study is needed to confirm and/or clarify the presence of intra and/or interspecific differentiation. Also, an Amazonian form from southern Brazil has recently been described as a new species, the Giant Peccary (P. maximus), although peccary specialists have questionedits taxonomic validity. Variationsin size and pelage color, coupled with distribution data, have been the basis for proposing the existence of fourteen subspecies of Collared Peccaries, but the inheritance oftraits has not been tested or otherwise substantiated.

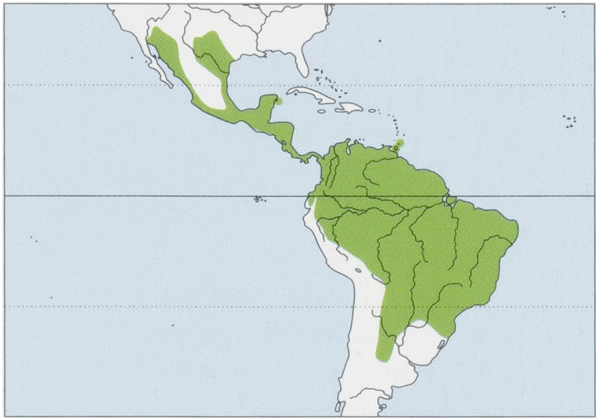

Subspecies and Distribution.

P.t.tajacuLinnaeus,1758—AmazonBasintoNArgentina.

P.t.angulatusCope,1889—SUSA(SENewMexico&Texas)throughNEMexico.

P.t.bangsiGoldman,1917—CPanamaalongNWColombia.

P.t.crassusMerriam,1901—ECMexico(SSanLuisPotositoVeracruz).

P.t.crusnigrumBangs,1902—NicaraguatoWPanama.

P.t.humeralisMerriam,1901—WCMexico(ColimatoOaxaca).

P.t.nanusMerriam,1901—SEMexico(CozumelI).

P.t.nelsoniGoldman,1926—SMexico(Chiapas&SYucatanPeninsula)toBelizeandCGuatemala.

P.t.migerJ.A.Allen,1913—SWColombiaandWEcuador.

P.t.nigrescensGoldman,1926—SGuatemala,ElSalvador,andHonduras.

P.t.patiraKerr,1792—NSouthAmerica(Colombia,Venezuela,theGuianas,NEPeru,andthetopendofNC&NEBrazil).

P.t.sonoriensisMearns,1897—SWUSA(SArizona&SWNewMexico)toWMexico(SonoratoJalisco).

P.t.torvusBangs,1898—NWSouthAmerica(SColombia,Ecuador,andNCPeru).

P. t. yucatanensis Merriam, 1901 — SE Mexico (Tabasco & N Yucatan Peninsula) to N Guatemala.

Collared Peccaries are also present in Trinidad and Tobago and it seems likely that they belong to the subspecies patira. However, assesmentofthis is yet to be done. The Collared Peccary was introduced to Cuba in 1930, butis no longer found in the wild there. View Figure

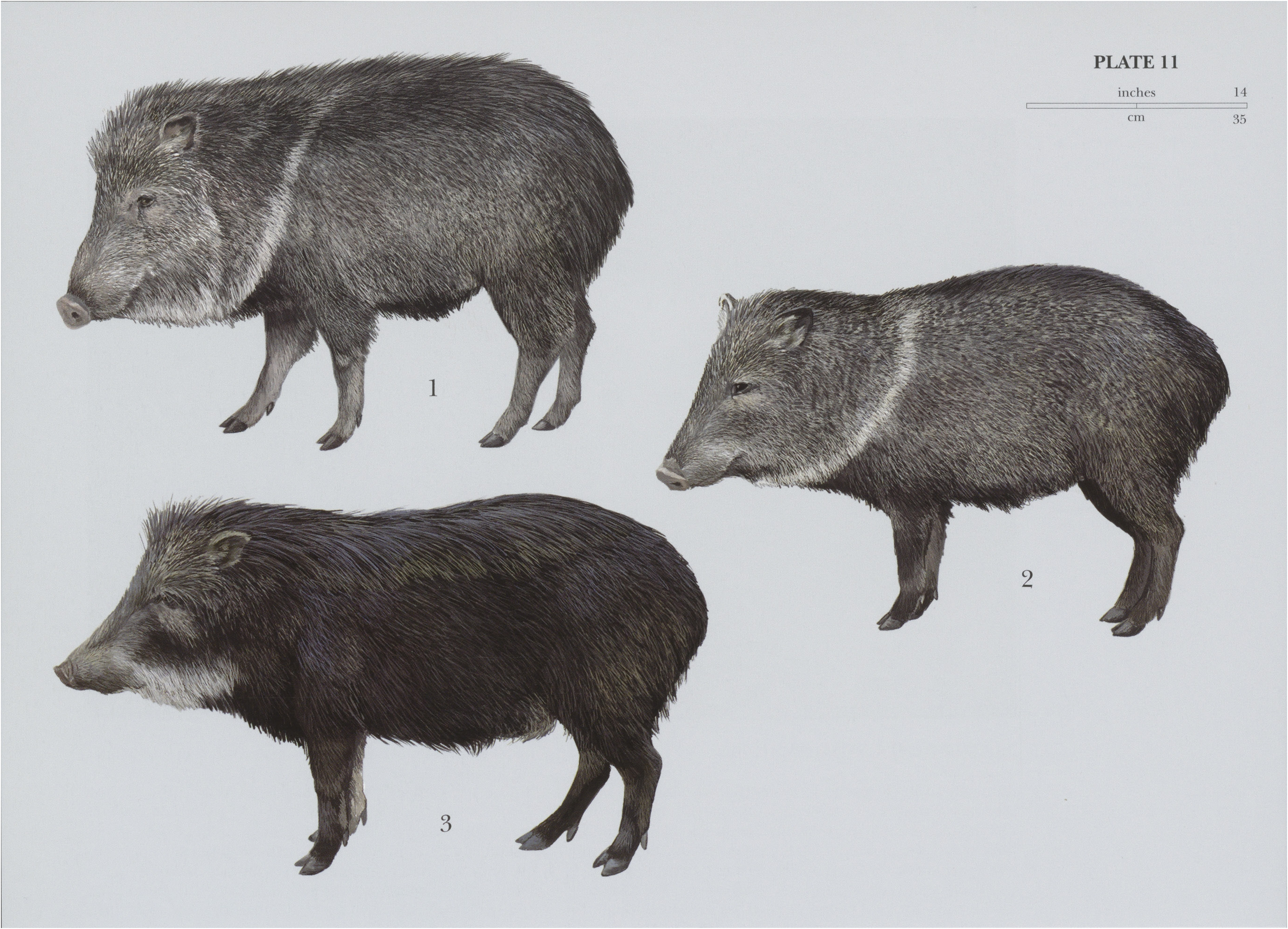

Descriptive notes. Head—body 84-106 cm, tail 1-10 cm, shoulder height 30-50 cm, ear 2:7.9-8 cm, hindfoot 16-25 cm; weight 15-28 kg, but reaching 40-42 kg in Arizona and Peru. There is one inguinal and one abdominal pair of mammary glands. The coat color is typically speckled dark blackish-gray, blacker on the limbs and along the dorsal crest, with a whitish band or collar passing across the chest and shoulders. More reddish or dark brownish coat colors are found in some populations. Also, the characteristic paler collar may vary from highly distinct in some individuals to barely discernable in others. The juvenile coat is grizzled reddish-tan with a distinct dark brown mid-dorsal stripe and pale shoulder collar.

Habitat. The Collared Peccary is the most widely distributed of the three extant species. It has wide climatic tolerance and is adapted to a variety of habitats and ecosystems. It inhabits subtropical and tropical ecosystems including rainforest, semi-arid thorn forest, montane cloud forest, deserts, islands, scrublands, savannas, and freshwater wetlands. The upper limit of its range along the Andean foothills is 1000-1500 m. However, there are reports of this species being found at up to 2000 m above sea level in Ecuador, and exceptionally up to 3000 m in the Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala. At the northern limit ofits range, Collared Peccaries are found in areas where midday temperatures reach 45°C, relative humidity is below 6%, annual rainfall is less than 250 mm, winter nighttime temperatures fall below 0'C, and light snow cover is occasionally present. At the other extreme, it inhabits tropical forest where average midday temperatures are around 27C, with high humidity (80%) and annual rainfall that often exceeds 2000 mm per year. In the Pantanal of Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay temperatures average about 24-25C, but can range from 0°C to 40°C with yearly rainfall of 1000-1400 mm. This species’ tolerance for low seasonal temperatures is exceptional for an animalalso living in the tropics, emphasizing its behavioral and physiological adaptability.

Food and Feeding. The collared Peccary uses its mobile lips and snout, and its welldeveloped sense of smell, for finding and manipulating food, as well as to monitor its surroundings. Its diet is as diverse as its wide distribution and the range of habitats it occupies. It feeds on a variety of plants and plant parts including roots, bulbs, tubers, fruits, seeds, and the edible parts of green plants, as well as small invertebrates and vertebrates. Diets vary seasonally depending on food availability. In tropical forests, Collared Peccaries are highly frugivorous, consume fruit from over 128 plant species, and eat seeds from some 79 species. In desert environments the cladophylls of prickly pear cactus (Opuntia) are an important source of food as well as water. This animal plays an important role in seed dispersal, maintaining tree species diversity, and otherwise affecting the structure and plant species composition of its habitats.

Breeding. Collared Peccaries breed throughout the year, with peaks from November to March in the northern border of the species’ distribution. In the Peruvian Amazon peaks in conceptions were observed in January, July, August, and October. The gestation period is from 141 to 151 days and usually 1-2 offspring are born, butlitter sizes of up to four have been reported. The young follow their mothers within an hour of parturition, stopping to suckle at frequent intervals. Infants have been observed to spend up to 24% of their time suckling. Weaning occurs at approximately six weeks. Females may have more than one mate during the estrous cycle and no long-term pair-bonds appear to exist, although dominant males in groups seem to have higher mating success. However, details of the mating system and familial relationships have not been validated through genetics.

Activity patterns. Collared Peccaries have a generally diurnal/crepuscular activity pattern, typically feeding in the early hours of the night, but varying seasonally depending on temperature, food availability, and hunting pressure. They appear to travel more in the early morning and late afternoon when the full herd is together. Collared Peccaries rest during the late morning and early afternoon in small groups of 3—4 individuals, typically in burrows, caves, underlogs, or in cavities excavated at the bases of large trees and next to fallen trunks. In the intense heat of the Gran Chaco, they tend to be more nocturnal. They also wallow in mud or dust, butit is uncommon to see them grooming themselves.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Collared Peccary herd size varies from six to over 30 individuals, depending on habitat. Density range is from 1-1-10-9 ind/km? in the USA, 2-8 ind/km? in the gallery forests and the Llanos of Venezuela, fewer than 1-6-6 ind/km? in the Pantanal of Brazil, and 5-9 ind/km? in tropical forests. Exceptionally large groups, of about 50 have been seen in the Brazilian Amazon where White-lipped Peccary ( Tayassu pecari ) populations have declined, suggesting that interspecies competition may limit group size. This speciesis generally territorial, and defends a core area from conspecifics. Home ranges average approximately 150 ha, varying from 24 ha to 800 ha, specifically: 102-287 ha in the semi-deciduous Atlantic forest in south-eastern Brazil, 64-109 ha in north-western Costa Rica, 460-543 ha on Maraca Island of Brazil, 685 ha in the Paraguayan Chaco, and 157-243 ha in French Guiana (including overlapping areas between adjacent herds). The dorsal gland of the Collared Peccary contains both sebaceous and sudoriferous secretory tissues that produce some 20 volatile components, some specific to males or females. They deposit scent on each other, as well as on tree trunks, rocks, and other objects, likely to mark range boundaries. Eight types of vocalizations have been identified including purring, grunting, barking, woofing, growling, and squealing as well as jaw snapping. It is believed that vocalizations and scent help keep the herd together. Collared Peccary group and subgroup membership are reported to be stable, with data suggesting that individuals rarely move between herds. However, radio-tracking in Arizona documented the acceptance of outsider male into herds; and observational and genetic studies have shown strong subadult male-biased dispersal among 13 social groups in Texas.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II, except populations of Mexico and USA, which are not listed. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Although this species is widely distributed, and occurs in a variety of habitats,its status requires monitoring as it is ecologically important and helps maintain livelihoods of local people. Further,its taxonomy needs urgent updating as some possible taxonomic units (species or subspecies) are likely vulnerable. In Argentina, the species was extirpated from the provinces of Corrientes, Entre Rios, Santa Fe, South of Cordoba, and South-east of Santiago del Estero. The principal threats to the Collared Peccary, like other members of this family, are overhunting for subsistence and the bushmeat and hide trade, as well as habitat loss and degradation. These factors have fragmented populations and led to local extinction. Impacts on population dynamics, subgroup interactions, and genetic diversity could reduce this species’ ability to adapt to environmental challenges and introduced diseases. Collared Peccaries are commercially valuable in Peru where approximately 50,000 pelts are legally exported annually under CITES. They were originally included in Appendix III of CITES but were moved to Appendix II in 1986, in part to tighten restrictions on trade in peccary products to help conserve the endangered Chacoan Peccary. Pelts are tanned in Peru and primarily sold to the European leather industry for the manufacture of high quality gloves and shoes. Collared Peccaries are protected by laws and regulations across much of their range, butillegal harvesting and inadequate protection and/or enforcement is common. Populations are managed for sports hunting in the USA. In Texas, efforts to restore populations have been successful, but translocations need to insure that group and family structures are maintained. Accidental release of captive Collared Peccaries in areas distinct from their geographical origin has happened and should be prevented to reduce unnecessary gene flow between lineages and disease risks. The species is expanding northwards and it is colonizing areas between the ranges of the two Collared Peccary subspecies in the south-western USA.

Bibliography. Adega et al. (2006), Albert et al. (2004), Altrichter & Boaglio (2004), Altrichter, Carrillo et al. (2001), Altrichter, Saenz et al. (2000), de Azevedo & Conforti (2008), Barreto et al. (1997), Beck (2005, 2006), Beck et al. (2008), Bissonette (1982), Bodmer (1989a, 1989b), Bodmer & Sowls (1993), Bodmer, et al. (1990), Builes et al. (2004), Byers & Bekoff (1981), Castellanos (1983), Chebez (2008), Cooper et al. (2010), Corn & Warren (1985), Culen et al. (2000), Day (1986), Desbiez et al. (2009), Donkin (1985), Eisenberg (1980), Gongora, Bernal et al. (2000), Gongora, Morales et al. (2006), Gongora, Taber et al. (2007), Gottdenker & Bodmer(1998), Green et al. (1984), Grubb & Groves (1993), Hall (1981), Hannon et al. (1987), Hellgren et al. (1995), Keddy & Fraser (2005), Keuroghlian & Eaton (2008a, 2008b), Keuroghlian et al. (2004), Kiltie (1981a, 1981b, 1985), Lamit & Hendrie (2009), Mayer & Brandt (1982), Mayor et al. (2007), Nogueira et al. (2007), Ojasti (1996), Packard et al. (1991), Peres (1996), Pontes & Chivers (2007), Robinson & Eisenberg (1985), Schaller (1983), Schweinsburg (1971), Sowls (1984, 1997), Stangl & Dalquest (1990), Taber et al. (1994), Tedfilo et al. (2007), Terborgh et al. (1986), Varona (1973), Vassart et al. (1994), Waterhouse et al. (1996), Weckel et al. (2006), Wetzel (1977a, 1977b), Woodburne (1968), Wright (1998).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pecari tajacu

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Sus tajacu

| Linnaeus 1758 |