Rhinolophus megaphyllus, J. E. Gray, 1834

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.3748525 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3808912 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/885887A2-FFD4-8A35-F8B7-FBE7F962D7FC |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Rhinolophus megaphyllus |

| status |

|

52 View On . Eastern Horseshoe Bat

Rhinolophus megaphyllus View in CoL

French: Rhinolophe à grande feuille / German: Östliche Hufeisennase / Spanish: Herradura de hoja grande

Other common names: Smaller Horseshoe Bat

Taxonomy. Rhinolophus megaphyllus J. E. Gray, 1834 View in CoL ,

“ Novâ Hollandiâ [= Australia], in cavemis prope fluvium Moorumbidjee [= in caves near the river Murrumbidgee , New South Wales]. ”

Included in the megaphyUus species group, along with R keyensis , R virgo , R madurensis , R celebensis , R mbinsoni R chaseni R nereis , R bomeensis , R malayanus , and R acuminatus, although the taxonomy of this species group and other Oriental species groups is still in need of clarification. The megaphyllus group is placed in a broader clade including the Australo-Oriental lineage of Rhinolophus . The philippinensis group may also be best included within the megaphyUus group, as otherwise the megaphyUus group is paraphyletic with respect to. philippinensis . Another taxonomic solution would be to split the megaphyllus group into several smaller species groups, although this requires more complete taxon sampling. Queensland populations of R megaphyUus seem to be closer to R achilles (previously included in R philippinensis ) than to Victorian and New Guinean R megaphyllus . Thus, R megaphyllus most likely represents a species complex of at least two species, but further morphological and genetic testing is needed. Some authors have treated the Asiatic R robinsoni and R keyensis as subspecies of R megaphyllus , but they are generally recognized as distinct species, based on morphological and genetic differences. Specimens from southern Vietnam tentatively identified as R megaphyllus by G. Csorba and colleagues in 2003 probably represent R chaseni The subspecies currently recognized herein may turn out to be distinct species, based on genetic and morphological variation. Five subspecies are currently recognized.

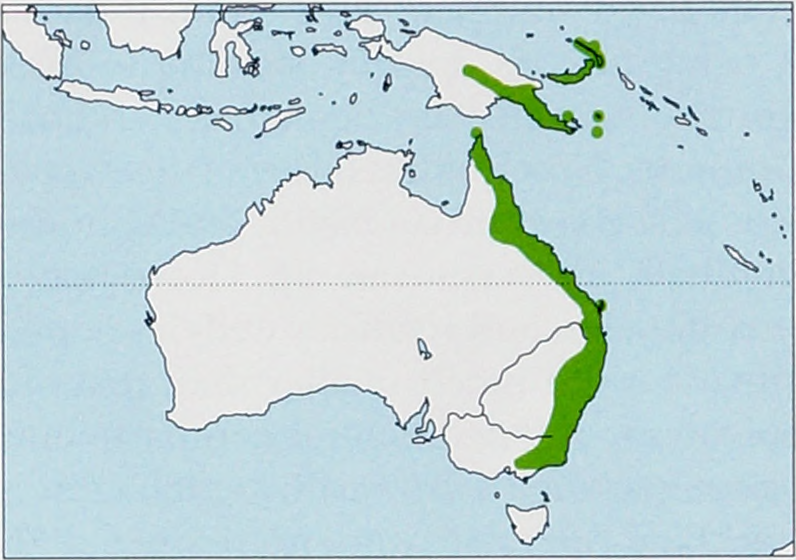

Subspecies and Distribution.

R m. megaphyllus J. E. Gray, 1834 - SE Australia (E New South Wales and E Victoria).

R m. fallax K. Andersen, 1906 - W to SE New Guinea and D’Entrecasteaux Is (Goodenough).

R m. igniferG. M. Allen, 1933 - NE Australia (E Queensland and Prince ofWales and Fraser Is).

R m. monachus K. Andersen, 1905 - Louisiade Archipelago (Woodlark and Misima).

R m. vandeuseni Koopman, 1982 - Bismarck Archipelago (New Ireland, Lihir , and New Britain). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 42-58 mm, tail 24- 6-28 mm, ear 17-21 mm, forearm 44—52 mm, weight 7-14 g for Australia; head-body 42-7-49- 8 mm, tail 18-21- 6 mm, ear 16-8-19- 5 mm, hindfoot 12- 1 mm, forearm 41-7-48- 7 mm, weight 6- 5-12 g for Melanesia. The Eastern Horseshoe Bat is morphologically variable. Dorsal pelage is either grayish brown to dark grayish brown (gray morph) or bright rufous (orange morph; can be found roosting with gray individuals in Queensland), while ventral pelage is slightly lighter. Ears are of medium length. Noseleaf has long lancet with straight or slightly concave sides, and pointed to more or less blunt tip; connecting process is high (higher than sella tip), rounded, and hairy; sella varies between subspecies, being wide and abruptly constricted in middle with upper margin slightly convex in megaphyllus and fallax, but narrower, less constricted in middle, and not broader at base than at top in monachus, horseshoe is wide, at 8-3—9- 2 mm, nearly covers muzzle, has small but noticeable median emargination, and has lateral leaflets that are mostly covered by horseshoe. Lower lip has three mental grooves. Baculum is moderate in length (c. 2-7 mm long) and has long, thin shaft with wide bifurcated base; in lateral view near base, there is small lobe followed by sharp downward curve before straightening out toward rest of thick base; tip is very slightly wider and rounded. Skull is of medium build (zygomatic width is slightly larger than or subequal to mastoid width); anterior nasal swellings are moderately developed and semicircular in outline; lateral compartment is conspicuously inflated and larger than anterior compartment; sagittal crest is low; frontal depression is longer than wide and clearly defined; supraorbital crestsjoin sagittal crest at more or less behind mid-orbit; rostrum is elongated. P2 is small with well-developed cusp and is within tooth row or slightly displaced labially, separating C 1 and P4 widely; P3 is variably in tooth row, partially displaced, or fully displaced labially, depending on subspecies.

Habitat. Tropical and temperate rainforest, deciduous vine forest, dry or wet sclerophyll forest, and open woodland, as well as coastal scrub and grassland habitats; most active in mature primary forests. Eastern Horseshoe Bats prefer to forage around dense vegetation near waterways, while avoiding more open environments. They have been recorded from sea level up to 1600 m, but acoustically detected at 250-2350 m on the Huon Peninsula (YUS Conservation Area), New Guinea.

Food and Feeding. Eastern Horseshoe Bats are insectivorous and forage primarily by fly-catching and perch-hunting, as well occasionally as vegetation and ground gleaning. They specialize in foraging in cluttered environments, like many other rhinolophids; they are highly maneuverable and can even hover for a few seconds. Their primary prey is non-eared moths, but they also feed opportunistically on beedes, flies, crickets, true bugs, cockroaches, and wasps. Once prey is captured, it is usually taken to a temporary night roost to be consumed, leaving the ground below it littered with wings and legs that the bats have discarded. These bats are also known to feed on particular insects within their caves, specifically Speiredonia spectans and S. mutabilis (Erebidae) , which are species of eared moth found cohabitating with this species in caves year-round; the moths are able to detect the calls of this species and sometimes avoid predation mid-flight. These moths are used most as a food source during hibernation in the southern portion of the range, when there are no insects active outside the cave.

Breeding. Eastern Horseshoe Bats exhibit restricted seasonal monoestry. Spermatogenesis occurs in February and sperm is available in March. Copulation, ovulation, and fertilization occur in lateJune, which is when spermatogenesis halts; males store sperm in the epididymis for at least another four months. Unlike many horseshoe bats in more temperate regions, female Eastern Horseshoe Bats do not seem to store sperm, and males do not produce a vaginal plug. Gestation lasts 4-4-5 months, depending on how much the mother goes into a torpid state during pregnancy. A single young is bom around November and clings to the mother during infancy, becoming independent and beginning to forage on its own, before it reaches adult size. Young are weaned at c.8 weeks after reaching adult size after 5-6 weeks. Males reach sexual maturity after 18 months, whereas females take 36 months. Maximum longevity has been recorded at seven years, although this species may live longer, as in other rhinolophids, due to its restricted breeding rate as a result of seasonal monoestry and only having a single young.

Activity patterns. The Eastern Horseshoe Bat is nocturnal, feeding throughout the night and reentering the cave at dawn, to roost throughout the day. It can enter torpor during the day and in the southern portion of its distribution, it can hibernate during cold winters, becoming increasingly torpid from April toJune and decreasingly torpid from June to September. Day roosts are typically found in warm, humid large caves and abandoned mine shafts, and other man-made subterranean places. The species will also inhabit rock piles, buildings, tree hollows, old railway tunnels, tree roots in creek banks, stormwater drains, and culverts, generally finding roosts with restricted entrances and narrow vertical drops; it roosts in the dark portions of the caves rather than near the opening. Call shape is FM/CF/FM with a peak F of c.68 kHz on the Huon Peninsula (YUS Conservation Area), New Guinea and 67-71 kHz in north-east Queensland, Australia.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Eastern Horseshoe Bats are highly gregarious and can be found in colonies of up to thousands of individuals, although most colonies number only 5-50. Adult males have high roost-site fidelity and are more sedentary than adult females, which will fly up to 20 km to reach a maternity roost in September or October each year. Females create very large maternity colonies when giving birth and raising their young, the largest recorded colony consisting of over 10,000 individuals in a sandstone cave near Sydney. Females return to their nonmatemity caves in March or April, forming mixed-sex colonies that persist through the winter months where they hibernate in the southern portion of their distribution. The species is often found roosting with other species of Rhinolophus and Miniopterus in both Australia and New Guinea.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN ed List. The Eastern Horseshoe Bat has a relatively wide distribution and is rather common. However, it is sensitive to roost disturbance, especially during their breeding season. Habitat destruction also seems to be a major threat, as local populations generally decline after major alterations and clearance of vegetation near roosting sites. The species seems to be less common in the southern portion of its range. Destruction or gating of abandoned mine shafts are also threats to this species.

Bibliography. Armstrong & Aplin (2017g), Balcombe & enton (1988), Bonaccorso (1998), Churchill (2008), Cooper eta/. (1998), Csorba et al. (2003), enton (1982b), Flannery (1995a, 1995b), Fullard et al. (2008), Hall et al. (1975), Jones & Corben (1993), Kerle (1979), Kitchener, Schmitt et al. (1995), Krutzsch et al. (1992), Pavey (1998), Pavey & Burwell (1998a, 1998 b, 2004), Pavey & Young (2008), Richards (1989), Robson et al. (2012), Slade & Law (2007), Stoffberg et al. (2010), Vestjens & Hall (1977), Young (1975, 2001), Zhang Lin et al. (2018).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Rhinolophus megaphyllus

| Burgin, Connor 2019 |

Rhinolophus megaphyllus

| J. E. Gray 1834 |