Robaloscion wieneri, (Sauvage, 1883) (Sauvage, 1883)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.26028/cybium/2020-441-004 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10881734 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/96033314-FFF8-FFFB-FF1B-4DD5FA68FE7E |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Robaloscion wieneri |

| status |

|

Robalo ( Peru, Chile), Robalo drum (English), Courbine de Wiener (French).

IUCN status

Data deficient (DD).

Identification

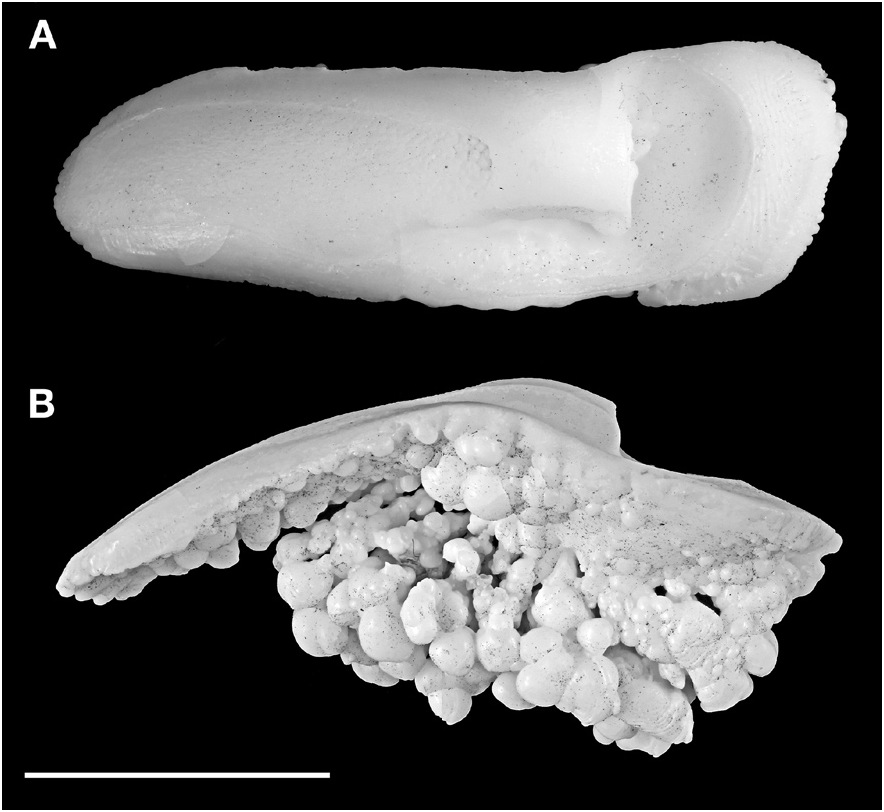

D X-I/21-23; A II/10; P 19; V I/5; C 19; lateral line complete with 77 scales; mouth terminal ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ); gas bladder carrot-shaped, with a pair of horn-like appendages anteriorly; otolith exceptionally elongate with globose umbo on the outer face ( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ); body bluish grey to brown with wavy darker stripes on sides; adult length to 140 cm and maximum weight 35 kg (Landa, 1952; Béarez and Schwarzhans, 2013). Drawing from Starks (1906), photography in Béarez and Schwarzhans (2013).

Biology and ecology

Occurs along sandy and pebble beaches (PB, pers. obs.) as well as in superficial waters around coastal islands ( Fiedler et al., 1943; Landa, 1952). At flood times, the robalos congregate at the mouths of rivers ( Fiedler, 1944: 97; Schweigger, 1964: 261). This species feeds primarily upon fish (Peruvian anchoveta, Engraulis ringens ; Pacific menhaden, Ethmidium maculatum ), but its diet includes also crustaceans (freshwater shrimp, Cryphiops caementarius ; sand crab, Emerita analoga ; burrowing shrimp, Callichirus garthi ).

Little is known about robalo’s reproduction, except that adults probably used to aggregate in estuaries to spawn ( Fiedler, 1944), when river discharge is important (i.e. November to January). The Peruvian fishermen used to find the robalo listening to the noise like a drum that this species makes ( Fiedler et al., 1943). A large male (137 cm TL) caught on 6 March 2000 at the mouth of the Camaná River GoogleMaps , Peru (16°37.7S- 72°46.1W) was mature and fluent. As for other sciaenids, spawning is probably paired with production of pelagic eggs. The size at sexual maturation is unknown.

Depth range is neither well known, but fishermen consider that the species lives in inshore waters from December to May, and in deeper waters (25-30 m depth) during the rest of the year ( Fiedler et al., 1943: 283).

Distribution

Temperate South-Eastern Pacific, from Puerto Eten (06°56’S, northern Peru) to Arica (18°28’S, northern Chile). The robalo drum is an endemic species of the northern part of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem ( Béarez and Schwarzhans, 2013).

Abundance

No modern abundance record. Once a common and prized species ( Fiedler, 1944), the robalo drum is now uncommon wherever it occurs, and is no more recorded in IMARPE (Instituto del Mar del Perú) fisheries national statistics. For example, Fiedler et al. (1943) indicate that landing of robalo during 1940 was 25,995 kg at Callao (Lima), 37,397 kg at Chimbote ( Peru) and up to 65,135 kg at Pacasmayo. IMARPE statistics do not report any landing of robalo at these harbours since 1988 ( Flores et al., 1994), and today robalo is no more considered a commercial species ( Guevara-Carrasco and Bertrand, 2017).

Main threats

These include: (1) intense and selective fishing for drums: Robalo, as well as corvina, Cilus gilberti (Abbott, 1899) , and lorna, Callaus deliciosa (Tschudi, 1846) , are among the most popular commercial fish in Peru ( Schweigger, 1964: 259); (2) decrease in the flow of coastal rivers ( ONERN, 1972), limiting feeding and reproduction; (3) capture by destructive and non selective fishing, especially beach seining; (4) capture as by-catch in the Peruvian anchovy purse seine fishery; (5) no management at local or national level; (6) continued trade because its high value increases with rarity.

Protection status

None

Conservation measures implemented

None

Conservation recommendations

(1) Implement a moratorium on fishing to limit population decline. (2) Fund research on R. wieneri ecology and behaviour, and especially reproductive season and behaviour. (3) Create marine reserves that incorporate key habitat, such as spawning areas. (4) Educate fishermen, resource managers, consumers and the general public on the importance of recognizing and conserving this species, which closely resembles to Cilus gilberti . (5) Develop culture program based on technology already applied to other sciaenids (e.g. Totoaba or Argyrosomus species). (6) Restore river flows in estuaries at spawning season. Remarks: The large size attained by this species suggests that it may be long-lived, and with a low replacement rate, which makes it particularly vulnerable to fishing pressure. There is little chance that culturing will remove pressure on wild-caught individuals in the near future because sciaenids are difficult to culture.

According to its current rarity, it is clear that R. wieneri is really threatened and that its IUCN species status should be re-evaluated.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |