Petauroides volans (Kerr, 1792)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6670456 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6762303 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9A5ECE23-4D28-386E-FF49-6F7DFE18E9E7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Petauroides volans |

| status |

|

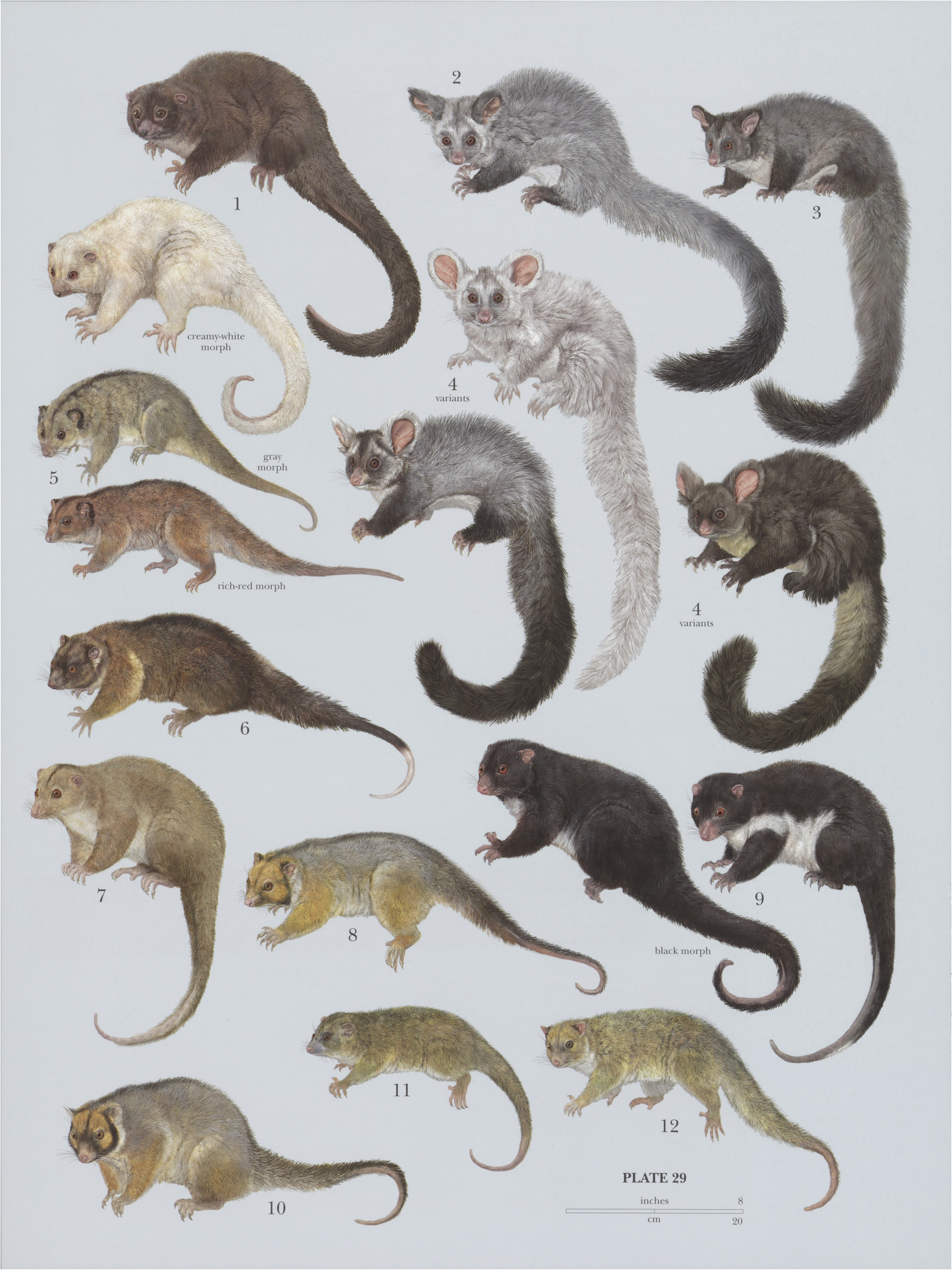

4. View Plate 29: Pseudocheiridae

Southern Greater Glider

Petauroides volans View in CoL

French: Possum volant / German: Sidlicher GroRRflugbeutler / Spanish: Falangero planeador grande meridional

Other common names: Greater Glider, Greater Gliding Possum

Taxonomy. Didelphis volans Kerr, 1792 ,

“ New South Wales,” Australia .

Two subspecies are recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

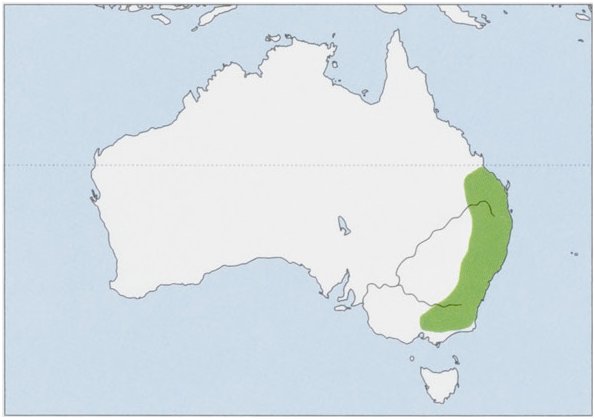

P.v. volans Kerr, 1792 — E Australia, from Bundaberg on the SE Queensland coast and the C New South Wales coast S to Orange and Port Macquarie/Bulga Plateau. P v. incanus Thomas, 1923 — SE Australia, including parts of New South Wales (N to upper Hunter Valley) and Victoria.

Distributions of volans and incanus appear to overlap or at least interdigitate, but the nature of the contact zone is unknown. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 35-45 cm, tail 45-60 cm; weight 0.9-1.7 kg. The Southern Greater Glider is the largest gliding marsupial and has a well-developed gliding membrane that extends from elbow to ankle on each side of the abdomen (in gliders of the genus Petaurus , Petauridae , patagium extends from wrist to ankle). Head of the Southern Greater Glider is short, with pointed muzzle and large, oval-shaped ears that are furred externally but naked inside. Fur is thick and shaggy, and tail is long, evenly bushy, and pendulous, and it has a small naked area on ventral surface at the tip; tail is much longer than the body. Pouch is well developed and contains two teats. The volans subspecies typically has dark brown or gray fur, but color morphs with variable amounts of cream fur are common, ranging from small patches on head and extremities of limbs, progressing through to entire body. The incanus subspecies is typically gray brown, basically similar to the Central Greater Glider (P. armillatus) but has larger body size and proportionally larger ears.

Habitat. Variety of types of eucalypt forest, from low, open forests on the coast to tall forests and even low woodlands west of the Great Dividing Range. In many parts of the distribution of the Southern Greater Glider, it appears to be most common in highelevation, moist old-growth tall eucalypt forests and wet eucalypt forests with larger diameter trees and more tree hollows, and less common in low-elevation, dry sclerophyll forests. Its presence in particular locations likely reflects a productivity gradient that incorporates not only characteristics of the substrate, such as nutrient properties, but also prevailing microclimatic and topographic conditions (including rainfall, solar radiation, temperature, aspect) that influence site productivity and plant growth. In some regions, Southern Greater Gliders may be associated with only a handful of plant species. For example, in south-eastern Queensland, a model predicted that Cor ymbia citriodora and Eucalyptus tereticornis (both Myrtaceae ) were important parts of the habitat selected by Southern Greater Gliders, as were live, hollow-bearing trees that are often a limited resource in southern Queensland. Within its broader distribution, the Southern Greater Glider has a patchy distribution, with one study finding that 52% of the forest contained no individuals.

Food and Feeding. The Southern Greater Glider feeds almost entirely on young leaves, buds, and flowers of trees of the myrtle family ( Myrtaceae ) in the genus Eucalyptus . It can be highly selective; three-quarters of its diet can be species in the subgenus Monocalyptus, with the subgenus Symphyomyrtus and genus Corymbia less important. In one study at Tumut in south-eastern New South Wales, the diet included leaves and buds of the ribbon gum (E. viminalis), mountain gum (E. dalrympleana), and narrow-leaved peppermint (FE. radiata), with 72% of observations coming from these three species. E. radiata is also a widely preferred species in Victoria. Other species that appear to be important in different parts of the distribution of the Southern Greater Glider include E. cypellocarpa, E. fastigata, E. globoidea, E. moluccana, E. ovata, E. obliqua, E. regnans, and E. tereticornis. There are occasional feeding observations on non-eucalypts, including leaves of the native Acacia (Fabaceae) and Amyema (Loranthaceae) and young cones and buds of introduced radiata pine (Pinus radiata). Small stomach capacity of the Southern Greater Glider and its diet of eucalypt leaves play an important role in energy expenditure, with individuals spending most of their time feeding and resting. Southern Greater Gliders spend most of their time resting, with short bouts of feeding. Gutilling effect of eucalypt foliage, slow digestion rates, and low levels of nutrients in leaves may limit amount of time spent feeding.

Breeding. The Southern Greater Glider is monovular and polyestrous. Single young are born in March—June, with most young born in April-May. Young spend 90-120 days in the pouch and then ¢.90 more days being carried on their mothers’ backs before gradually becoming independent at 10-11 months of age. No paternal care has been observed, so contribution of males is currently unknown. Little information is available on dispersal of young, although it has been presumed that some of them inherit a part of their mothers’ home ranges. Adult males are believed to be antagonistic toward their male offspring and may be the cause of the observed female-biased sex ratio (c.1:1-6) that characterizes at least some populations. Both sexes attain sexual maturity in their second year. Breeding probably occurs annually, but it appears that only 60-75% of adult females breed each year.

Activity patterns. As with all other pseudocheirids, the Southern Greater Glider is nocturnal. Adults are largely solitary and spend only 25-30% of their active time feeding and spend long periods inactive. They typically forage in the upper canopy, which facilitates their gliding behavior and allows them to maximize glide distance. One study in south-eastern New South Wales found Southern Greater Gliders visiting an average of only six trees per night (including den tree) and feeding on an average of three trees, each of which was usually a different species. Most trees (96%) were used by a single individual. When more than one Southern Greater Glider was in a tree, cooccupants generally were an adult male and female (assumed mates) or females with their offspring.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Southern Greater Gliders are relatively sedentary, reflected by their small home ranges that are typically 1-2—4-4 ha for males and 0-9-1-7 ha for females, although a male glider in southern Queensland had a home range of 19-3 ha. Home ranges can overlap within and between sexes, but individuals appearto closely associate with each other only during the breeding season. Studies also suggest that home range size of Southern Greater Gliders increases with increasing patch size and reduced patch density, so small patches of habitat have more animals per unit area and have smaller home ranges and greater home range overlap. This suggests a degree offlexibility in their use of space. In traversing their home ranges, Southern Greater Gliders can make glides of up to 100 m. Reported densities typically vary from 0-01 ind/ha to 5-5 ind/ha, with densities thought to be related to concentrations of nutrients in foliage of particular tree species. It also appears that some aspects of social organization of the Southern Greater Glider may change with density. For example, mating system was proposed to be facultative polygyny in a low-density population (0-56 ind/ha) in Victoria, with four males being bigamous and five being monogamous. Another study in Victoria found that males occupied exclusive home ranges and maintained sole access to consort females by an amalgamation of femaleand resource-defense. Where patches were large enough for only two gliders, the two were usually a male and female, but where patches could accommodate three gliders, a male and two females occurred together (hence facultative polygyny). Mating associations may be influenced by presence or absence of concentrations of high-quality food. At sites with high-quality food, a bigamous mating system was observed, whereas at sites with low-quality food, Southern Greater Gliders were monogamous. Den sharing has been observed occasionally, although the relationship of individuals to each other has often not been well understood. In one study in south-eastern Queensland, den entrances were an average of 11 m above the ground in trees that were 20 m tall. Southern Greater Gliders use 4-20 dens in eucalypt trees that are from c.70 cm to more than 190 cm in diameter. Males use more dens than females. It appears that each individual frequently uses several trees and many other den trees are used infrequently. Commonly used trees appear to be situated in or close to the core area of the individual's home range. Sharing of den trees, either concurrently or independently, was predominantly between adult males and females or adults and their young. In one study in south-eastern Australia, both sexes were more likely to use a given den tree on successive days in April-October. This usage may be related to females raising young and males trying to maintain territorial boundaries and monopolize access to females. Predation of Southern Greater Gliders by the powerful owl (Ninox strenua) can be significant in south-eastern Australia. A study in an unlogged forest in south-eastern New South Wales recorded a 90% reduction in population size in less than four years as a result of predation by a single pair of owls.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Southern Greater Gliders show a negative association with intensive logging, so retention of patches and corridors of mature eucalypt forest that contain hollows is important. It is essential to manage forest remnants to ensure suitable habitat for Southern Greater Gliders over the long term. One study suggested that populations of Southern Greater Glider could be maintained at or near pre-logging levels when at least 40% of original tree area is retained and when there are strips of unlogged forest in riparian areas. Although Southern Greater Gliders can persist in unlogged riparian reserves if these contain large tree hollows for denning, they appear to be slow to recolonize disturbed areas.

Bibliography. Bennett et al. (1991), Cunningham et al. (2004), Eyre (2006), Foley, Kehl et al. (1990), Foley, Lawler et al. (2004), Harris & Maloney (2010), Henry (1984), Hume (1999a), Kavanagh (1988, 2000, 2002), Kavanagh & Lambert (1990), Kavanagh & Stanton (2005), Kavanagh & Wheeler (2004), Kehl & Borsboom (1984), Lawler, Foley & Eschler (2000), Lawler, Foley, Eschler, Pass & Handasyde (1998), Lindenmayer, Cunningham et al. (1990), Lindenmayer, Pope & Cunningham (2004), Lunney, Menkhorst, Winter et al. (2008), McKay (2008), Moore et al. (2004), Norton (1988), Pope et al. (2004), Smith, G.C. et al. (2007), Smith, R.FC. (1969), Tyndale-Biscoe & Smith (1969a, 1969b).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Petauroides volans

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Didelphis volans

| Kerr 1792 |