Myomimus roachi (Bate, 1937)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6604339 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6604460 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9B215C43-FFD4-DD12-CC64-F484F5F3F951 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Myomimus roachi |

| status |

|

19. View On

Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse

French: Loir de Roach / German: Mausschlafer / Spanish: Liron de Roach

Other common names: Bulgarian Dormouse, Mouse-tailed Dormouse

Taxonomy. Philistomys roachi Bate, 1937 ,

late Pleistocene sediments in Tabun Cave, Mount Carmel, northern Israel.

When this species was first detected in Bulgaria in the late 1950s, it was thought to represent M. personatus , whose nearest collecting locality was ¢.3800 km east in north-eastern Iran. In 1976, O. L. Rossolimo recognized that the Bulgarian population represented a separate species of mouse-tailed dormouse and described it as a new species, M. bulgaricus , based on comparisons with extant species of mousetailed dormice. Fossils of this same animal (or a very close relative) from late Pleistocene sediments of Tabun Cave in northern Israel, an important Paleolithic site, had already been described in 1937 by D. M. A. Bate as a new genus and species under the name Philistomys roachi . Pleistocene fossils and recent subfossil material attributable to this species was also discovered at othersites in Israel, Greek Macedonia, eastern Aegean Islands, and southern Anatolia. In 1967, G. B. Corbet and P. A. Morris compared their subfossil specimens from Anatolia with specimens of extant dormice from Bulgaria and the type series of P. roachi , and they concluded that they all represented the same species, but at that time, the Bulgarian dormice were considered to be M. personatus . Thus, Corbet and Morris proposed that P. roachi was ajunior synonym of M. personatus . In 1975, G. Storch, independently of Rossolimo, realized that the eastern Mediterranean fossil and extant dormice represented a species distinct from M. personatus and applied the valid species name “roach?” to these animals. Because the genus Myomimus was described in 1924 by S. I. Ognev, 13 years before Bate described Phalistomys, Myomimus is the valid generic name. Monotypic.

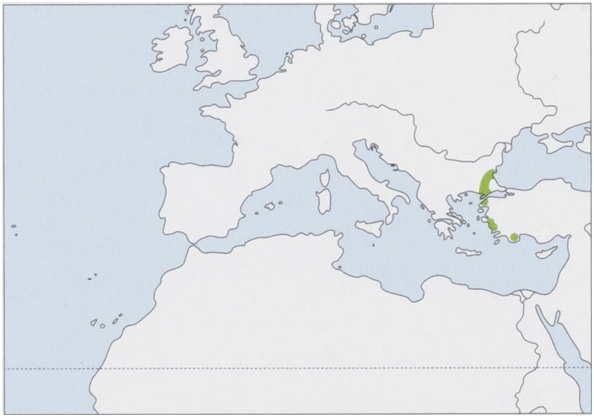

Distribution. NE Mediterranean region, fragmented distribution in SE Bulgaria and W Turkey (E Thrace and the Aegean coast of W Anatolia); it may occur in NE Greece. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 86-136 mm, tail 65-94 mm, ear 13-17-7 mm, hindfoot 19-23 mm; weight 21-70 g. No sexual dimorphism reported. Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse is the largest species in the genus. Dorsal pelage is brownish gray, sometimes with rufous hue and conspicuous darkening toward mid-dorsal line in most individuals that often appears as conspicuous irregular dark stripe from crown to rump. Ventral pelage is predominantly white or cream. Sides of body, face, and cheeks appear paler, and dorsal pelage is clearly demarcated from ventral pelage. Eye mask and dark eye-rings are absent. Hindfeet are white or grayish-white, c.19% of head-body length. Tail is moderately long (c.78% of head-body length), sparsely covered with gray and grayish-white hairs, appearing virtually naked, and is distinctly bicolored, dark gray above and grayish white beneath. Condylobasal length is 24-28-1 mm, zygomatic breadth is 13-6-16-2 mm, and upper tooth row length is 3:7-4-8 mm. External and cranial measurements are from Turkish and Bulgarian Thrace specimens.Chromosome number is 2n = 44. Females typically have seven pairs of nipples, one of the highest number in the dormouse family (2 pectoral + 3 abdominal + 2 inguinal = 14).

Habitat. [Lowland riparian forest and scrub and vineyards, orchards, and hedges that border cultivated fields. Availability oftree cavities in mature trees is a habitat requirement. Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice use tree cavities for daily rest sites and between bouts of nighttime activity. They have commonly been captured in hedges with trees and understory vegetation on edges of cultivated fields. In Turkish Thrace Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice were most often caught in trees, including fig, oak, willow, mulberry, and wild pear. A few individuals were captured on the ground or in blackberry bushes. Recent data from radio-tracked individuals discovered that they will occasionally forage in open grassland and will cross large open areas in search of food. While often associated with cultivation, Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice are absent from intensely farmed areas that lack wooded borders; they are likewise not found in forest habitats. Based on fossil and subfossil evidence, Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse was much more broadly distributed in the eastern Mediterranean region during the Pleistocene and Holocene. As B. KrysStufek and V. Vohralik point out in 2005, their modern habitat is steppe-like but is mainly cultivated; Mediterranean steppe vegetation may have been preferred habitat of ancestral populations.

Food and Feeding. Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse is omnivorous. Captive individuals reportedly prefer insects, especially mole crickets, grasshoppers, butterflies, and moths. In addition to insects and other invertebrates, they also readily ate lizards and a variety of fruits, seeds, and nuts. Studied stomach contents contained only green foxtail ( Setaria viridis, Poaceae ) seeds. Individuals have also been observed foraging in cherry, walnut, and almond trees, berry bushes, vineyards, wheat fields, and grassy meadows feeding on seeds and insects have also been observed.

Breeding. Litter sizes of Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice are 5-14 young and averages 8-2 young. Mating activity begins shortly after emergence from hibernation in late April or early May; females give birth at the end of May or beginning ofJune, c.44-51 days after emergence, according to observations of captive individuals. Gestation is c.30 days, and females probably produce one litter per year. Captive females gave birth to 5-6 offspring, but older females may have largerlitters, as evidenced by a female trapped in mid-May carrying 14 embryos; each measured c.4 mm. Birth weight of young bred in captivity has been reported to be 1-9-2-4 g; young gained an average of 0-24 g/day. After weaning at 29-31 days, young weighed 8-6-10-4 g and reached mean adult weight of 33-2 g by 120 days.

Activity patterns. Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse is nocturnal and crepuscular. Two peak periods of activity have been observed: the first and longest period of activity lasted 1-2 hours after sunset through around midnight, and the second period lasted between two hours before and two hours after sunrise. Observed individuals spent most daylight hours sleeping in tree cavities 1-4 m aboveground. They used cavities in several trees within their home ranges for daytime rest or between periods of nighttime activity. While sleeping during the day in tree cavities in the wild and in nest boxes in captivity, individuals were commonly found in state of daily torpor. On an extremely hot day, a Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse was observed covering the hole of its tree cavity with walnut and other tree leaves, presumably to insulate against influx of hot air. Hibernation begins in midto late November and lasts through late April or early May. For hibernation, captive Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice excavated burrows c.12 cm deep in the soil over several days and finally settled into hibernation. No nesting material was used, and the one entrance to the burrow was covered so that there was no obvious entrance. Three individuals hibernated together in one burrow, and two in the other, suggesting that in the wild individuals sometimes use common hibernacula. Of three adult individuals observed in captivity, two remained inactive under the soil for uninterrupted periods of 136 days and 142 days. One adult male emerged twice during the early days of hibernation and then finally settled in for 114 days.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice are probably solitary. They are arboreal and terrestrial; more individuals have been captured in trees than on the ground, and observations in the wild and in captivity documented individuals in tree cavities and foraging in trees, shrubs, and occasionally nearby fields and meadows. Home range size is poorly studied, but a study provided estimates for three individuals: 2071 m? for the only male; 2095 m? for one female; and 6646 m® for the second female. One female traveled more than 40 m through plowed fields with no vegetation cover. The male’s range overlapped that of both females, and females’ ranges overlapped slightly. Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormice rest in several different tree cavities within their home ranges for daytime rest or between periods of nighttime activity. Individuals commonly interchanged nesting cavities in areas where home ranges overlapped, using a given cavity for 1-3 nights. Different individual dormice will use the same nest cavity on consecutive nights, but in the wild, individuals were not recorded cohabitating nest cavities. Nesting behavior for Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse falls into two broad categories: nesting during the day when they are active and nesting during periods of hibernation. During their active season, they spend much of the day in tree cavities; no nesting materials are used on a regular basis. Captive females have been recorded beginning lining their nest boxes within a week of parturition.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. Roach’s Mousetailed Dormouse has a distribution ofless than 2000 km?, fragmented habitat, unknown potential threats, and low number of captured individuals. Although it may be locally common within very few localities such as Edirne in Turkish Thrace, overall population is thought to be declining. Krystufek and colleagues in 2009 further caution that distribution of Roach’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse is one of the smallest of all rodents in the western Palearctic region and that there is inadequate information available regarding population dynamics and trends. Major known threats include habitat destruction due to deforestation of buffer vegetation between cultivated fields, industrial agriculture, and degradation of habitat due to industrial activities and infrastructure.

Bibliography. Bate (1937), Buruldag & Kurtonur (2001), Civitelli et al. (1994), Corbet & Morris (1967), Georgiev (2004), Krystufek (2008), Krystufek & Vohralik (2005), Krystufek et al. (2009), Kurtonur & Ozkan (1991), Milchev & Georgiev (2012), Nedyalkov (2013), Nedyalkov & Staneva (2013), Ognev (1924), Peshev, Anguelova & Dinev (1964), Peshev, Dinev & Anguelova (1960), Popov (2011), Rossolimo (1976b), Simson et al. (1994), Storch (1975).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.