Acrorhinichthys, Taverne & Capasso, 2015

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2015.116 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DC7FCF48-1E85-4205-89CA-E1D49577F971 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3795204 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/D6858F4B-704F-48BC-8217-9DDDC44ACBEA |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:D6858F4B-704F-48BC-8217-9DDDC44ACBEA |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Acrorhinichthys |

| status |

|

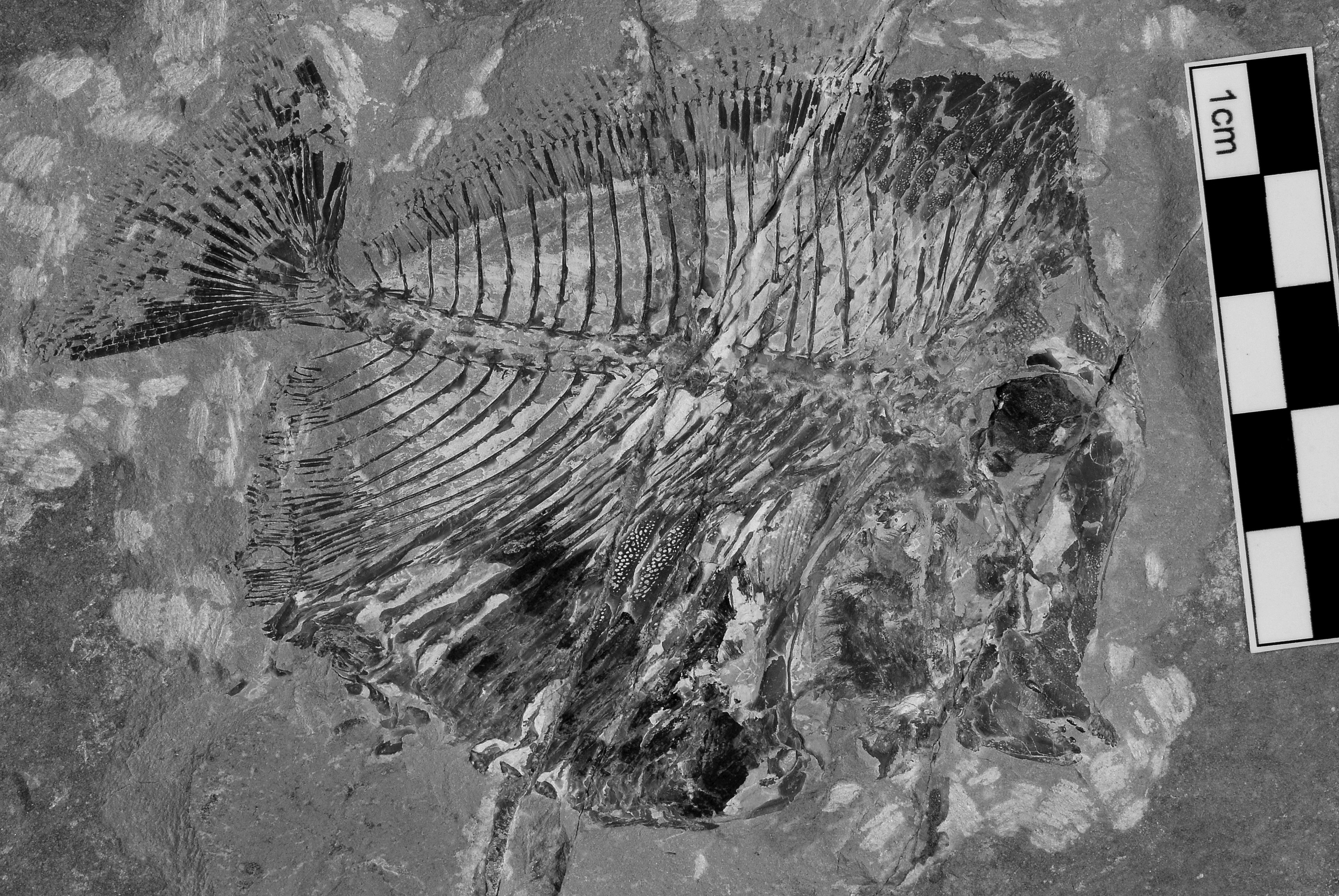

2. Acrorhinichthys gen. nov. within Pycnodontiformes

We hereafter use the phylogeny of Pycnodontiformes proposed by Poyato-Ariza & Wenz (2002, 2005) and based on cranial and postcranial characters.

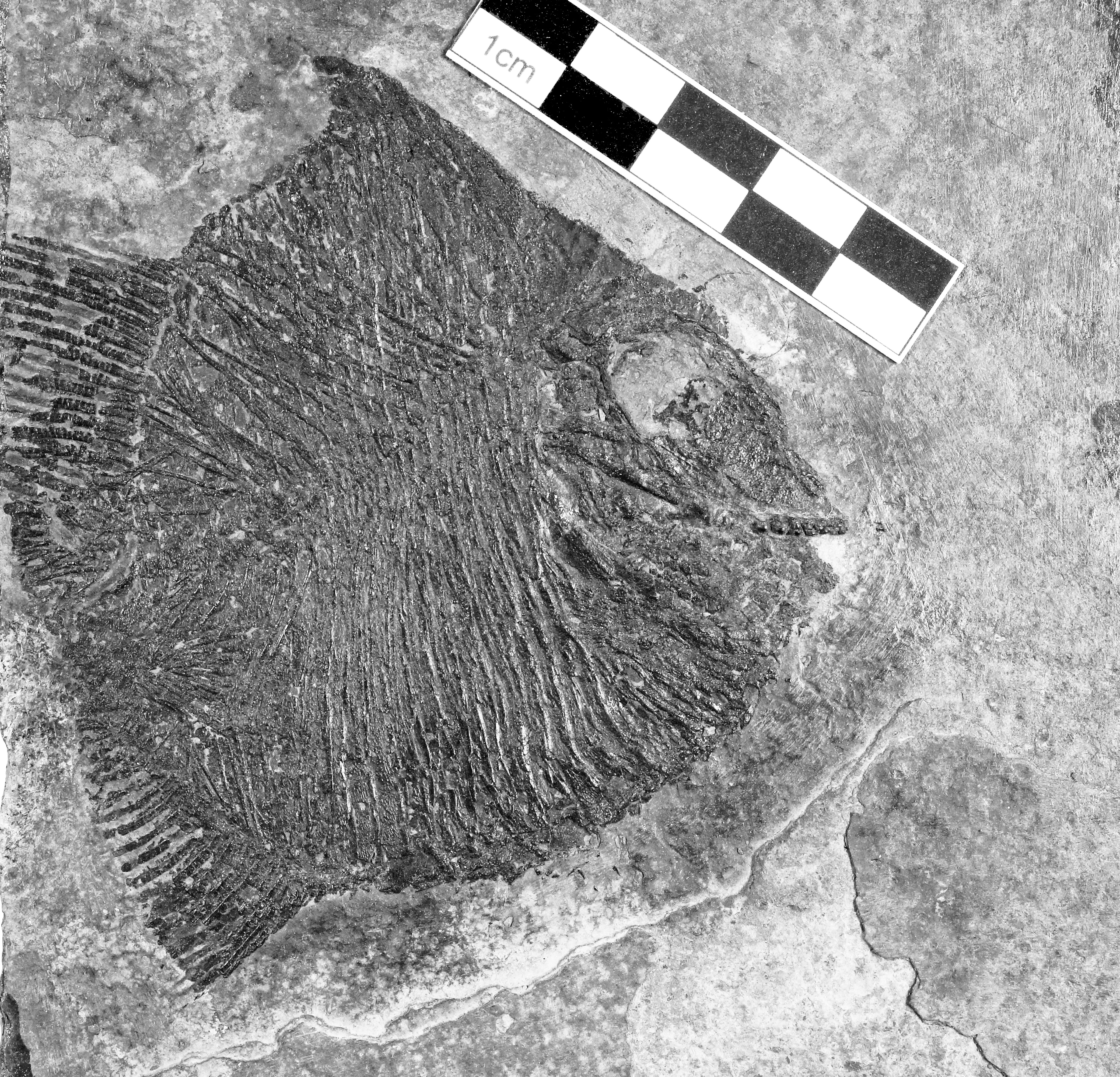

Brembodidae represents the most basal family and the most ancient lineage in the order ( Figs 20–23 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig ; Tintori 1980; Nursall 1996, 1999; Poyato-Ariza & Wenz 2002). They date from the Upper Norian (Late Triassic) of North Italy. Two genera are known, Brembodus Tintori, 1980 and Gibbodon Tintori, 1980 . They are deep-bodied fishes, with an important dorsal gibbosity or an elongate, spiny dorsal process. Brembodus still possesses two well developed dermosupraoccipitals, the posterior one being especially

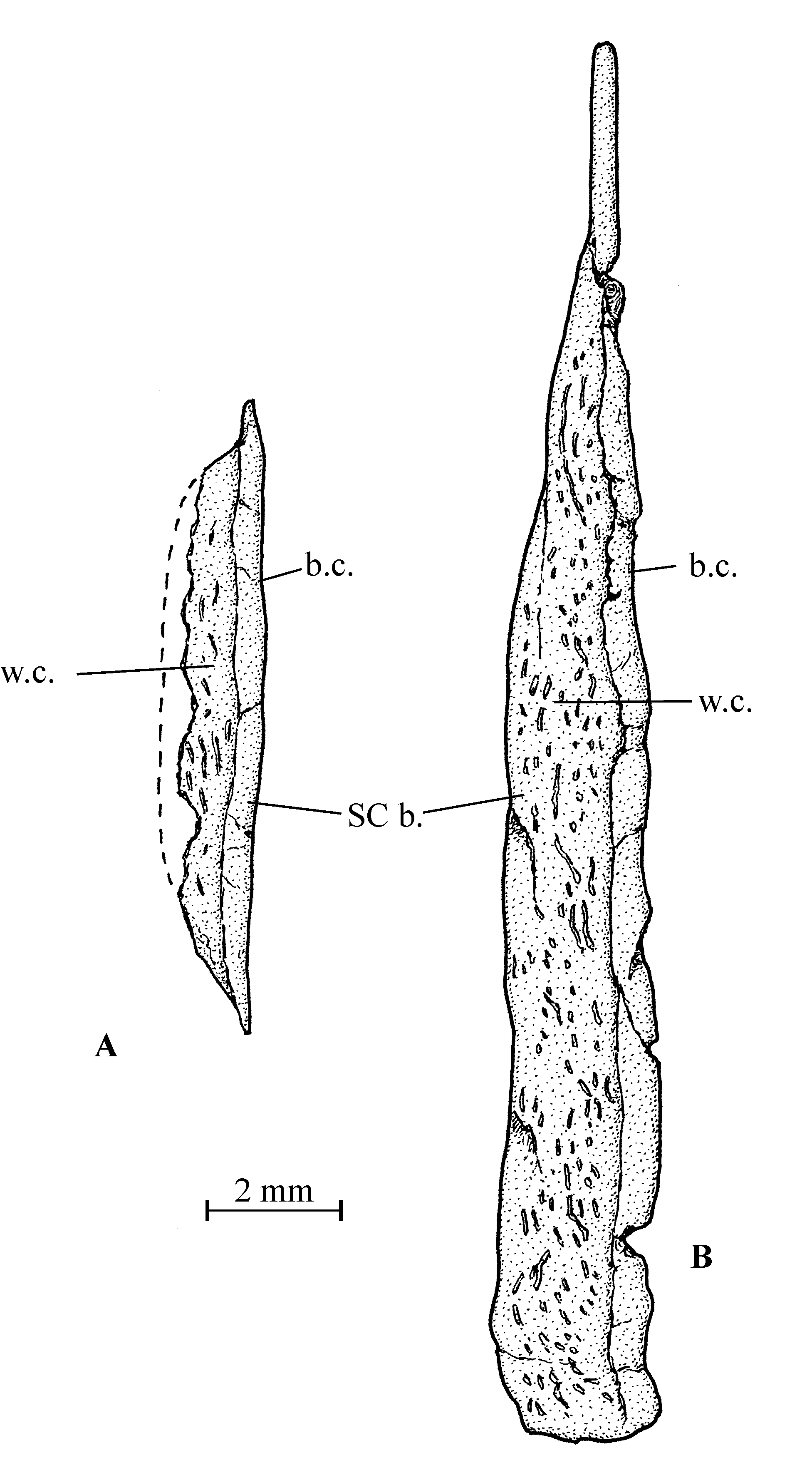

elongated. It is to be noted that Tintori (1980: fig. 1) considers the posterior dermosupraoccipital of Brembodus as the first scale of the dorsal ridge, and Nursall (1996: 145, character 94) and Poyato-Ariza & Wenz (2002: 195, character 84[1]) as a dorsal spine. However, this large bone not only articulates with, but is also sutured to the anterior dermosupraoccipital and the parietal, exactly as the posterior dermosupraoccipital in the five gyrodontiform genera. So, if this bone is considered as a posterior dermosupraoccipital in Gyrodontiformes, there is no valid reason to give it another name in B. ridens . The case of Gibbodon is more problematic. Tintori (1980: fig. 2) shows two dermosupraoccipitals in this genus but Poyato-Ariza & Wenz (2002, fig. 6 B) figure only one occipital bone preceding the first small dorsal scute. Both brembodid genera possess tubular posterior infraorbitals and a gigantic first infraorbital completely covering the cheek. They preserve small bony tesserae in the gular region. They have 3 teeth in the upper jaw and 4 or 5 teeth on the dentary. The margins of their unpaired fins bear fringing fulcra. There is a series of urodermals in the caudal skeleton. The scales cover their body totally as in Gyrodontiformes. However, these scales are much deeper than broad, with an important development of the bar component, while the flank scales of Gyrodus are less deep and the bar component is less marked ( Hennig 1906: pl. 11;, Lambers 1991: fig. 3a). There is a mosaic of small scales in the cloacal region of Brembodidae as in Gyrodus ( Poyato-Ariza & Wenz 2002: fig. 40A).

The new Lebanese fossil fish and the other Pycnodontiformes share at least two apomorphic characters not present in Brembodidae, i.e., the loss of the fringing fulcra and the presence of scales only in the abdominal region of the body.

Macromesodon Blake, 1905 (= Eomesodon Woodward, 1918 pro parte) seems to be the most basal member of this remaining group ( Woodward 1918; Poyato-Ariza & Wenz 2002, 2004). There is a large dorsal prominence as in Brembodidae. Tubular infraorbitals are present, but some bony tesserae are still covering part of the cheek. There is a series of 5 or 6 urodermals in the caudal skeleton. The cloacal region is still covered by a mosaic of small scales as in the most plesiomorphic Pycnodontomorpha . All body scales are completely ossified. Macromesodon is generally devoid of fringing fulcra on the impaired fins. However some rare samples still exhibit a few fringing fulcra ( Lambers 1991: fig. 25c; Poyato-Ariza & Wenz 2002: 192).

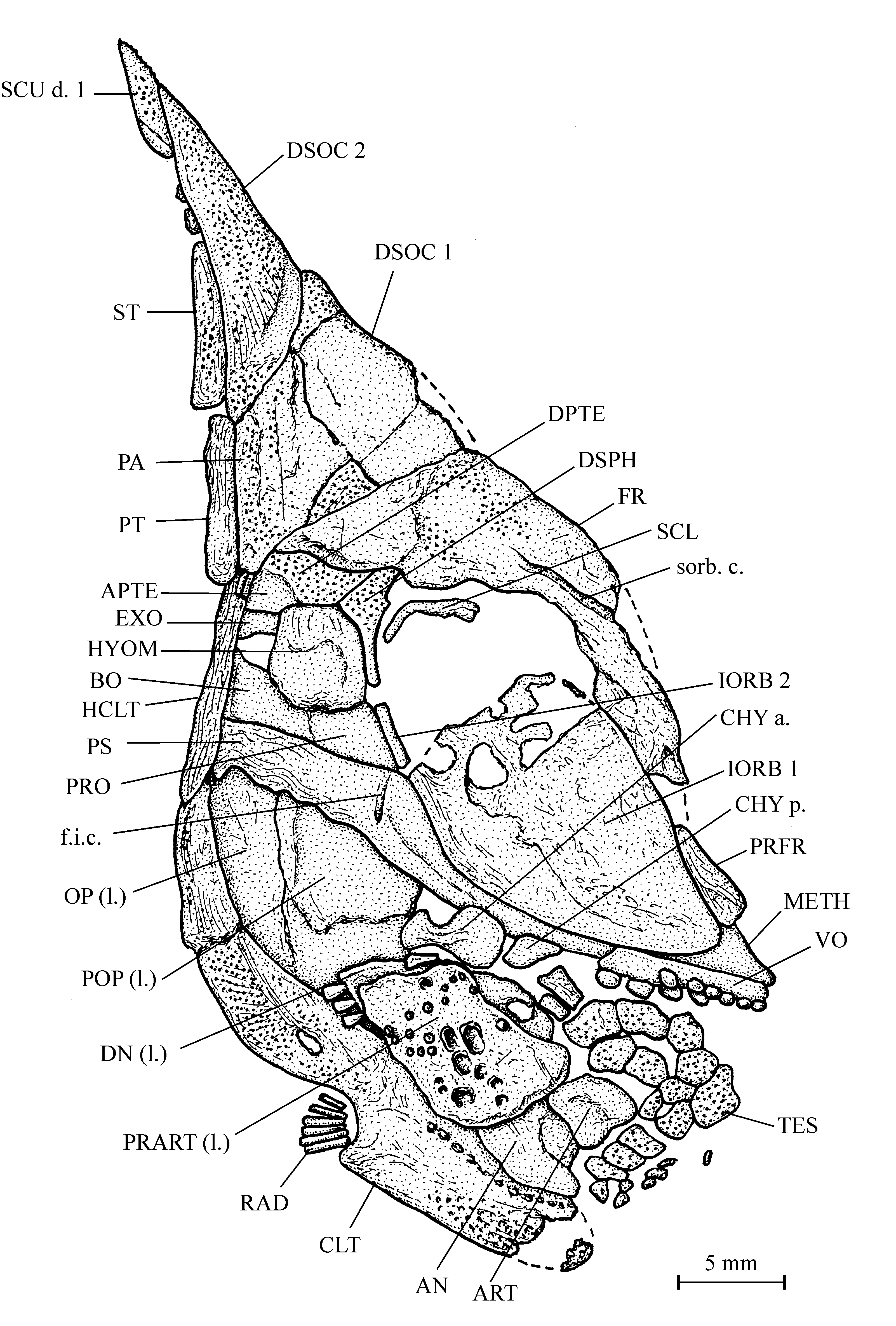

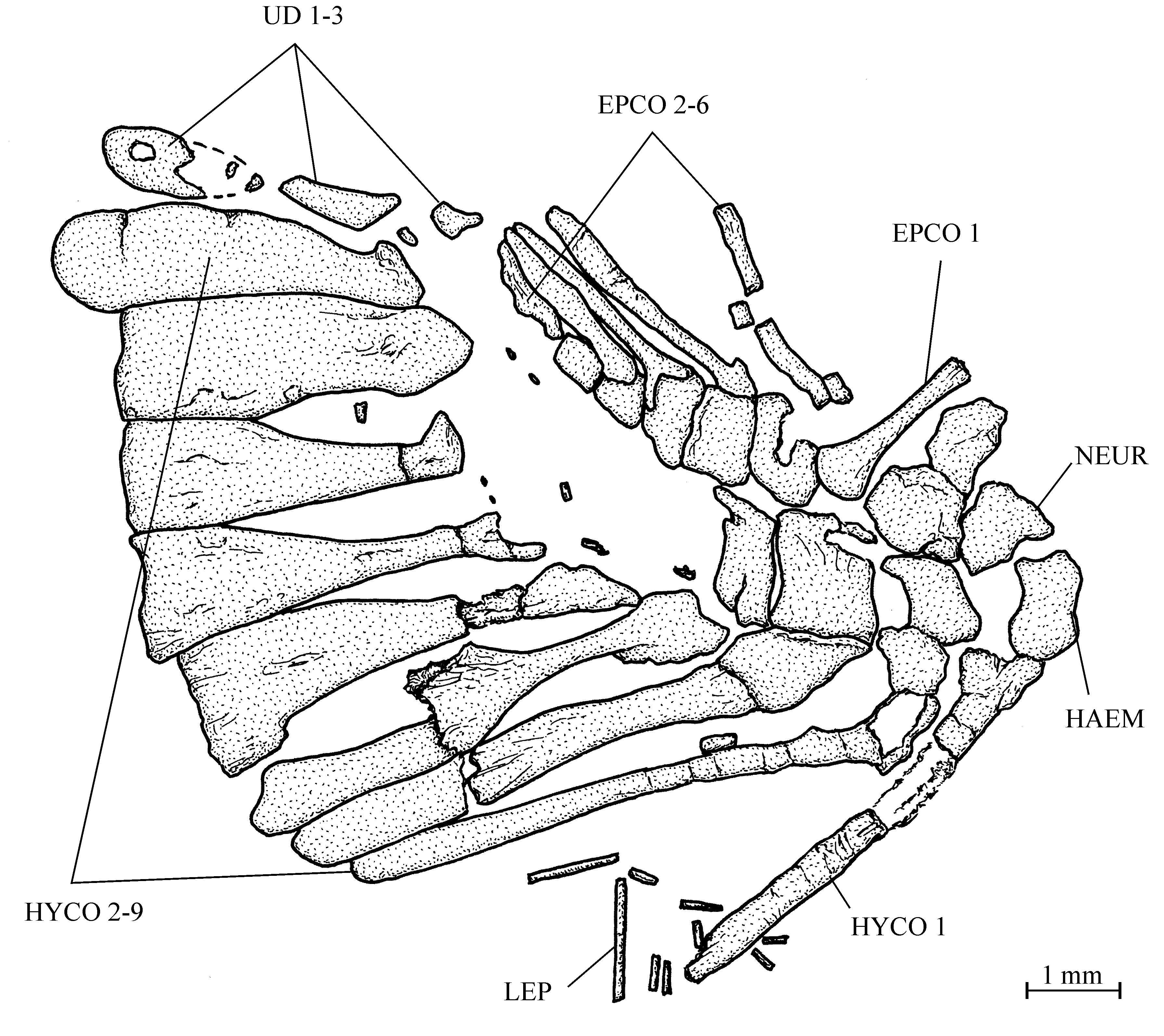

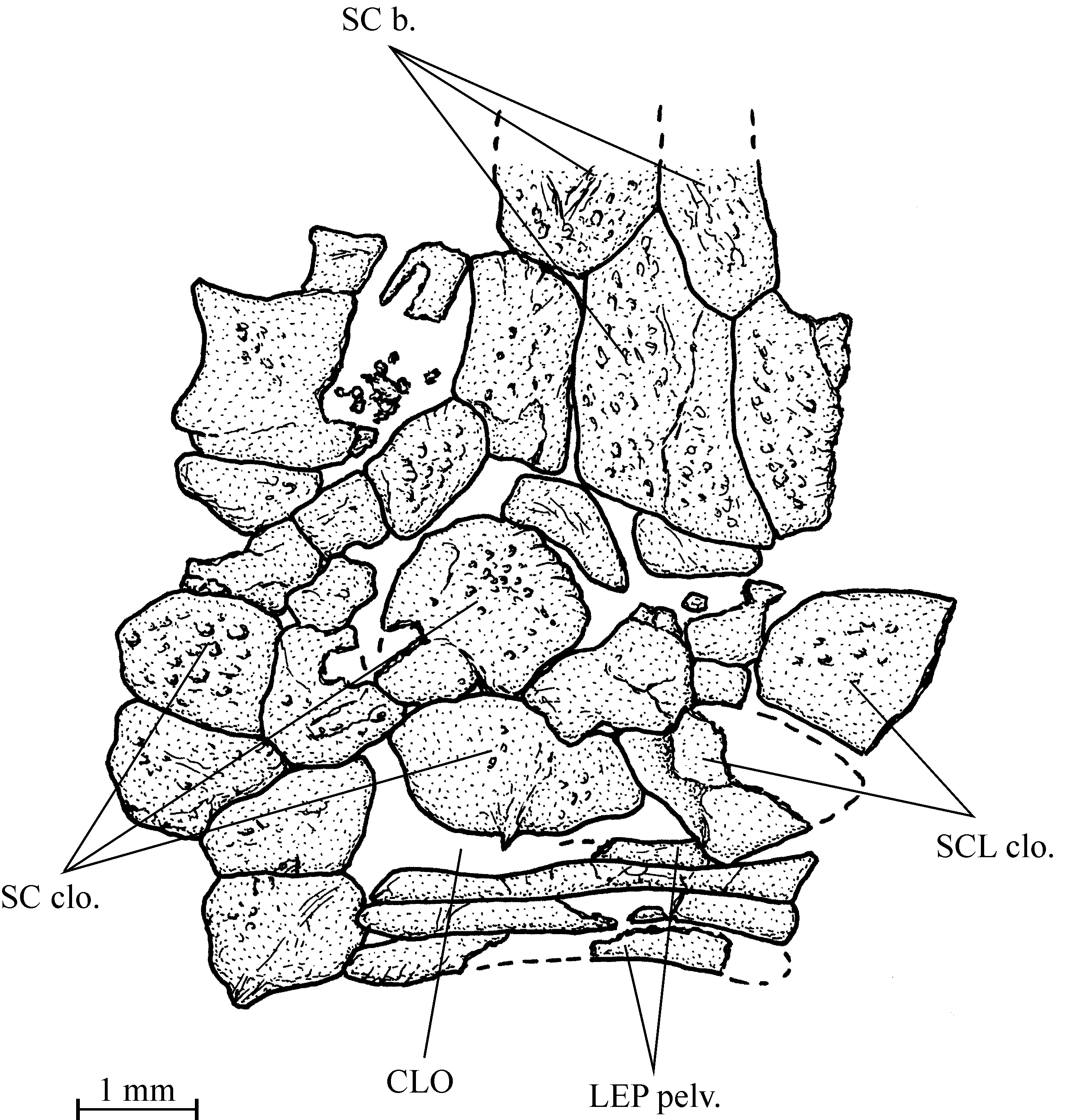

Acrorhinichthys gen. nov. and the more advanced Pycnodontiformes exhibit some new apomorphic characters. A dermohyomandibula is fused with the hyomandibula. There are anterior sagittal flanges on the neural and haemal spines. At least some neural and haemal arches are connected to each other by means of one or more postzygapophyses. The ventral keel contains less than 18 scutes. The urodermal series is reduced to 2, 1 or 0 elements. A part of the body squamation is composed of scale bars. The number of scales in the cloacal region is greatly reduced.

Acrorhinichthys gen. nov. is the most plesiomorphic genus within those remaining Pycnodontiformes . It still possesses a small dorsal prominence and a few gular bony tesserae, two plesiomorphic characters already disappeared in Coccodontidae , Gladiopycnodontidae , Gebrayelichthyidae and Pycnodontidae .

Coccodontidae , Gladiopycnodontidae and Gebrayelichthyidae are three highly specialized families of Pycnodontiformes ( Gayet 1984; Nursall & Capasso 2008; Capasso et al. 2010; Taverne & Capasso 2013a, 2014a, b, c). Their morphology and osteology are completely different from those of Acrorhinichthys gen. nov.

Pycnodontidae are principally characterized by the brush-like process of the parietal, a structure absent in Acrorhinichthys gen. nov. However, Akromystax Poyato-Ariza & Wenz, 2005 from the Cenomanian of Lebanon ( Fig. 24 View Fig ), the most plesiomorphic genus within Pycnodontidae , has preserved some archaic characters absent in the more evolved Pycnodontidae but present in Acrorhinichthys gen. nov., such as

a series of complete scales associated with the dorsal ridge scutes ( Poyato-Ariza & Wenz 2005: fig. 2), two imbricated complete cloacal scales, a small ventral triangular one and a deeper dorsal, one with a well developed bar component and a broad concave lower margin ( Fig. 25 View Fig ), and more than two teeth on the premaxilla and the dentary ( Poyato-Ariza & Wenz 2005: fig. 7).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |