Thamnophis eques diluvialis, CONANT, 2003

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1206/0003-0082(2003)406<0001:OOGSOT>2.0.CO;2 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/A27787BF-4D42-FF85-CD7A-FD0DFBC2FF4F |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Thamnophis eques diluvialis |

| status |

subsp. nov. |

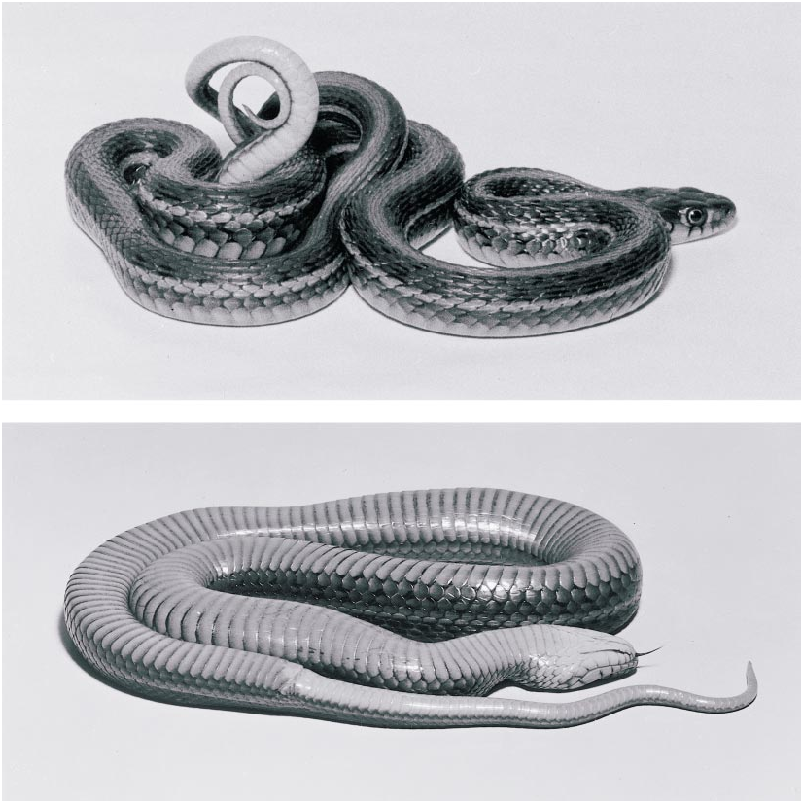

new subspecies Figures 10 View Fig , 12 View Fig , 13 View Fig

HOLOTYPE: AMNH 93966 View Materials , a mediumlarge male from near Villa Corona at the north end of the Laguna de Atotonilco , Jalisco, Mexico, collected August 16, 1964, by Roger Conant. Total length 756 mm, tail length 175 mm, tail/total length = 0.231.

PARATYPES: Several gravid diluvialis gave birth to young after our return from Mexico. Each mother’s number below is followed in parentheses by the numbers of her offspring. One female from Atotonilco and one from Cajititlán bore two litters, the second, in each case, about a year after the first. All localities are from the Mexican state of Jalisco .

Laguna de Atotonilco: AMNH 93959– 93978, 93979 (brood 93980–93984), 93985 (brood 93986–94005), 94006 (brood 94007– 94029), 94030 (brood 94031–94047), 96806 (brood 96807–96816), 96817, 94006 (2nd brood 96818–96835).

Laguna de Cajititlán: AMNH 96727– 96734, 96736, 96737 (brood 96738–96773), 96774 (brood 96775–96805), 96736 (2 broods not numbered—18 slightly premature, 29 normal).

Acatlán de Juárez: AMNH 94924, 94925.

Near Estipac: AMNH 94964.

Approximately 8 km west of Ixtahuacán de Los Membrillos: AMNH 91692.

Playa de Santa Cruz: LSUMZ 23578, 23579, 24554–24558.

ETYMOLOGY: From the Latin diluvialis, in reference to the overflowing of the land by water when the habitat was created by the huge rises in level of the Lago de Chapala.

DIAGNOSIS: A large, conspicuously palestriped snake in which the longitudinal middorsal stripe is a full three scales wide, involving the vertebral and paravertebral rows of scales and frequently small portions of the adjacent scales. Lateral stripes normally on rows 3 and 4 anteriorly, and rows 2 and 3 posteriorly. General dorsal coloration various shades of dark brown. Venter grayish, with a dark line across the anterior edge of each ventral scute. Chin, throat, and underside of tail yellow.

DESCRIPTION OF THE HOLOTYPE: The scutellation agrees with The Species Model, with the following exceptions: The postoculars are 4 instead of 3, and the lowermost extends slightly beneath the orbit. On the right side of the head a small scale is wedged

TABLE 4 Variation in Scutellation and Tail Length Proportions in Thamnophis eques diluvialis , New Subspecies

between the anterior temporal and the parietal.

Scale rows 211917, reducing to 19 by the loss of row 5 at the level of ventral 90 on the left and the level of ventral 87 on the right. Reducing again to 17 by the loss of row 4 at the level of ventral 116 on the left and ventral 117 on the right. Total ventrals 166; subcaudals 75. Tip of tail sharply point ed. Apical pits present, but difficult to find in this longpreserved specimen. Hemipenes not everted. Total length 756 mm, tail length 175 mm, tail/total length = 0.231. A summary of scale counts for the entire numbered sample from the Lagunas Atotonilco and Cajititlán and vicinity is in table 4. Many wildcaught specimens had incomplete tails.

Dorsally, this is a dark brown snake strongly patterned at midbody by a wide longitudinal stripe of medium or orange brown. Lateral stripes normally on scale rows 3 and 4 anteriorly; rows 2 and 3 posteriorly. In life, the lateral rows were greenish, but during long preservation they have changed to bluish. A double row of dark brown spots between the stripes on each side of the body that are inconspicuous against the general dorsal ground color of the dorsum. A row of similar dark spots below each lateral stripe. Top of head dark brown and unmarked, except for a faint, very small pair of parietal spots.

The anterior edge of each ventral is dark gray, approaching black, and collectively is part of a long series of crosslines that show clearly through the overlapping part of the preceding scale. The unmarked posterior portion of each scale is medium gray in coloration.

The chin, throat, and lower labials are yellow, but the throat is invaded by dark pigment on the scale preceding the first ventral. Most of the sutures between the infralabials are black, but in a few cases the dark pigment is lacking. The underside of the tail is brighter yellow than the chin and throat. The single (undivided) anal plate is colored the same, except for its lateral edges. It bears slight traces of the coloration and pattern of the ventral scutes.

VARIATION AMONG THE PARATYPES: In life, these were brown snakes, varying from pale to dark brown in general appearance, except for the three pale longitudinal stripes that were usually in strong contrast with the more somber hues of the rest of the dorsum. With the snake in hand, paired and alternating dark spots between the pale stripes were evident, but in photographs (figs. 12, 13) they were scarcely noticeable.

After being in preservatives for more than a third of a century, there have been many changes in color pattern, drastic in some specimens, minor in others. The broad (three scales wide) middorsal stripes may be in weaker or stronger contrast with the adjacent dark dorsum. The dark spots are visible in all specimens and they stand out in striking fashion in a few. The two lowermost rows of dorsal scales may show dark spots or pale rounded ones. The top of the head is dark brown, unmarked except for tiny parietal spots.

Dark lines across the anterior edge of each ventral. Remainder of belly usually grayish yellow; greenish or bluish in others. Undersides of chin, throat, and tail unmarked pale yellow. Anal plate similar, but dark pigment may encroach slightly from the sides.

Neonates in life were more or less replicas of the adults, except that they were paler. Af ter long preservation there were changes, notably fading and a concomitant strengthening of patterns. The paired dark spots between the lateral stripes became conspicuous. Pattern and color descriptions of two specimens are as follows:

(1) AMNH 94004, 228 mm in total length, a member of a litter of 20 born November 9, 1964; female parent (AMNH 93985) collect ed at the Laguna de Atotonilco on August 16, 1964. The paired dark spots are prominent and some of them are conjoined with their neighbors. Similar but smaller dark spots are continuous below each lateral stripe. A series of narrow dark lines is present where the dorsal and ventral scales meet and these form a continuous dark line in part. The dorsal stripe widens from a width of 3 scales to 5 on the nape and then narrows to a single scale where it meets the parietals. The result is a heart shape posterior to the almost black head. The belly is similar to that of adults. The chin, throat, and underside of the tail are pale yellow.

(2) AMNH 96800, total length 244 mm, from a litter of 31 born November 21, 1965, to a female (AMNH 96774) from the Laguna de Cajititlán collected July 28, 1965. Similar to the juvenile from Atotonilco, but the dorsal stripe widens only slightly on the nape. An intermittent dark line at the juncture of the dorsal and ventral scales forms part of the lowermost row of dark spots.

REPRODUCTION: Unlike our experience with obscurus at the Lago de Chapala where we found no gravid females, eight diluvialis in that condition were collected, five at Atotonilco and three at Cajititlán.

Dates of collection ranged from July 14 to August 16. Dates of birth of young were from September 7 to November 26. Late dates probably reflect the interruption of normal development of the offspring. The gravid females were kept inert in bags all through the long drive from the lakes to our home bases in and near Philadelphia.

The number of young in a brood varied from 5 to 36. The total lengths of the offspring were 171–244 mm, and the weights immediately after birth 2.0–4.7 g. One female from each of the two lakes, and which had been caged with one or more males, bore a second litter about a year later. In all, there were 207 young in a total of 10 litters, one litter slightly abnormal. Scale counts are available for most of these and are summarized separately in table 4.

A large female (AMNH 96736), 1015 mm in length, collected July 28, 1965, at the Laguna de Cajititlán, gave birth to two litters of young in captivity. The first, born September 5, 1965, and numbering 18, was slightly premature. The yolk sacs in all were completely free from the bodies, except for a narrow cord. None of the young showed any indication of crawling, but they extended their tongues, flattened their bodies, and even struck defensively. All hemipenes were inverted, with none visible externally. They were all flabby and did not preserve well. The same snake, caged for a while with a male, bore a normal litter of 29 young on July 26, 1966. Only the adult female was numbered. No scale counts were made on the young. The abundance of data available from neonates born to other females from Cajititlán was more than adequate.

To analyze all 10 broods would occupy an inordinate amount of space, but details are given below for the components of the largest brood, with information on sizes and weights.

A gravid female (AMNH 96737) measured 1031 mm in length and weighed 276.5 g immediately after the birth of her 36 young on November 17, 1965. She was collected on July 28, 1965, in the Laguna de Cajititlán. She was confined in a cloth bag on a pile of foam rubber in a storage space beneath the bed in our camper with a number of other gravid snakes. There she remained as we zigzagged across Mexico and then home, where we arrived 17 days and almost 4000 miles later. I inspected our live collection almost daily and each snake was given a chance to drink every few days. The mother ate sporadically at our home base, chiefly on small Rana pipiens . My notes, written on the day the young were born, state, ‘‘She is thin and spent but still vigorous, pugnacious, and fairly heavy.’’

Among the 36 young (AMNH 96738– 96773), 20 were males and 16 females. The males, after they were preserved and sexed by dissection, measured 214–233 mm in length, mean 224; the females 203–236 mm, mean 219. The live neonates were weighed but not sexed on November 19, 1965. Individual weights varied from 3.4 to 4.7 g, mean 4.0. Several of the tails of both sexes were slightly curled at birth. Two infertile ova were passed with the young.

Color notes were made after the young were euthanized and before they were preserved. Capitalized color names are from Ridgway (1912). The dorsal ground color was dark brown (Mummy Brown); the lateral coloration was paler (Dresden Brown). The middorsal stripe was an orangebrown (Buckthorn Brown) anteriorly, but it changed to a dark reddish brown (Prout’s Brown) for most of its length. The lateral stripes were light green (Deep Lichen Green). Top of head darker than ground color. Chin and throat pale yellow (Straw Yellow); underside of tail similar. Eye: pupil black bordered by yellow; iris OliveBrown. Tongue: Dragon’sblood Red at base, but becoming Brick Red anteriorly; tip black.

OCCURRENCE AT GUADALAJARA: Despite a search for one, no map is at hand to show the maximum extent of the lake or lakes that came into existence when the Lago de Chapala rose almost 200 m above its present level and spilled over ( Clements, 1963). How far north did it go? Did it reach the area of the present city of Guadalajara, which is now only about 25 km north of the Laguna de Cajititlán? The Atlas Goodrich Euzkadi (1964) shows changes in altitude in color throughout Mexico, and its map 17 indicates that low areas are currently present from Cajititlán all the way to Guadalajara so, presumably, it was possible for the flood waters to extend that far northward even though it was a very long time ago and may have been influenced by tectonic events.

There is some evidence that it may have extended at least that far. In the herpetological collection of the American Museum of Natural History there are nine specimens from Guadalajara (AMNH 3199–3202, 3206, 3207, and 3438–3440) that were collected a century ago (1899–1901) by L. Diguet, the Duke of Loubat, when the city was much smaller than it is today. All of these snakes are still in good condition, but they have fad ed and only the black pigment, chiefly that which composes the dark spots between the pale stripes, is conspicuous. The dark spots, which scarcely show in the accompanying illustrations (figs. 12, 13), were visible when the live snakes I collected were in hand during 1964 and 1965. After more than 35 years of preservation, some have changed rather slightly, whereas others have faded, two of them so much that they somewhat resemble the centuryold snakes.

An examination of the nine Guadalajara snakes reveals that the middorsal stripe is three scales wide as in specimens of diluvialis, but occasional small amounts of darker adjacent pigment invade the paravertebral scales. In six specimens, the dark spots are prominent; they are less so in the other three. All are of relatively large size, ranging in length from 539 to more than 800 mm. Tentatively, I place these nine old snakes in diluvialis.

EL LAGO DE MAGDALENA

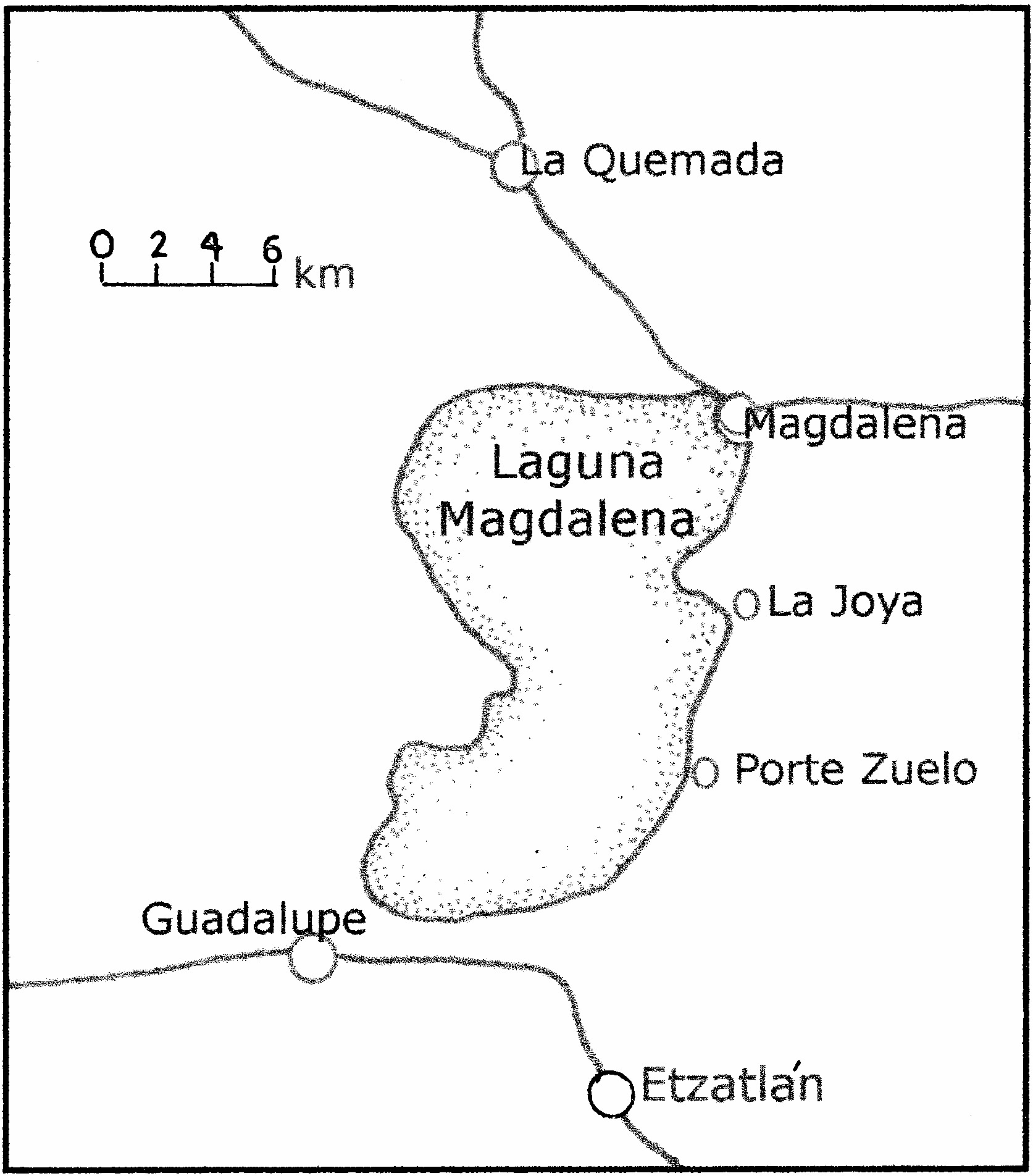

This large body of water, about 65 km westnorthwest of Guadalajara, was the west

ernmost of the endorheic lakes of the transvolcanic belt (fig. 1). Goldman (1951), in writing about the extensive peregrinations he and Edward A. Nelson made from 1892 to 1906 while collecting mammals and birds in almost all parts of Mexico, was in Etzatlán, Jalisco, in June 1892. He wrote that the town ‘‘is located at the southern end of the Laguna de la Magdalena, which is a body of water several miles wide and about 20 miles long, occupying a basin without outlet.’’

Two thousand and more years ago, the Lago de Magdalena was an important cultural center. About the time of the birth of Christ some of the Indian residents moved northward to found a new center in the Cañon de Bolaños (Cabrero G., 1991).

The lake had several towns along its eastern shore (fig. 14), the largest and northernmost of which was Magdalena. According to Tamayo with West (1964: 109–110), ‘‘in 1900 it was still supplying large quantities of pescado blanco to the Guadalajara area... ’’. By about the middle of the 20th cen tury, however, the lake had lost its water and ceased to exist.

How was the lake emptied? Where did its waters go? Tamayo (1949, II: 417) explained it by manmade sluiceways that discharged into La Colorada lake, which lies 13 km almost due south of the town of Magdalena (INEGI, Guadalajara sheet, 1:250,000, 1998).

Smith and Miller (1980: 416) hypothesized that the ‘‘Laguna de Santa Magdalena’’ was once drained to the Pacific Ocean by the Río Ameca, possibly when that river served as the outlet for the Río Lerma basin a very long time ago.

Our discovery of the remnants of the Lago de Magdalena was accidental. For reasons unknown, there was a customs checkpoint at Magdalena, far from any alien border. On July 12, 1959, we were stopped and required to produce our car and tourist permits. We were driving a station wagon and the rack of wooden drawers at its rear containing snakes in bags we had caught near Tepic, Nayarit, invited inspection. My collecting permit validated them, but it triggered a long conversation. The customs men stated that in a low area due south of their station snakes were numerous. A tight schedule prevented an investigation at the time, but when we returned on August 30, 1961, the abundance of Thamnophis eques was quickly confirmed. Details are given in my memoirs ( Conant, 1997: 217), the highlight being our discovery by headlamp at night of a slowly roiling ball of snakes perhaps ‘‘two feet wide and half as high’’, and composed of about 50 large snakes. I wanted to observe and study them, but two Mexican boys who had attached themselves to us rushed in to grab all they could. The serpents scattered and the boys spoiled a onceinalifetime opportunity for me.

We were back at the remains of the Lago de Magdalena on August 18, 1964, and we did a little exploring along the gravel and mud roads. The ‘‘lake’’ was far from empty. It contained numerous ponds, swales, and marshes, as well as the straightsided ditch on a ledge of which (fig. 15) we found the ball of snakes in 1961. The water in it flowed slowly. It was fairly shallow, scarcely above my booted knees. Other ditches drained wa ter away. Obviously, at least some of the sources that kept the lake full for centuries were still functioning. Water birds such as wood storks, egrets, gallinules, coots, and cormorants were much in evidence.

Our last visit was on July 7, 1965, accompanied by herpetologist James D. Anderson and his student, Robert Giacosie. We arrived in advance of and witnessed the first heavy rain of the season. Frogs and toads of many species emerged from estivation in large numbers, and snakes were gorging themselves on the sudden bonanza. Mostly, the predators were Thamnophis eques , but a few T. melanogaster also participated.

In summary, T. eques was abundant during all three of our visits. We refrained from catching all we saw, but, even so, including the many young born to gravid females, our voucher sample numbered 136.

The lake does not appear on modern maps, but the detailed sheet of the state of Jalisco in the Atlas Geográfico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (1946) shows the Lago de Magdalena southwest of the town of the same name. Artist W.H. Brandenburg developed a facsimile that appears as figure 14. He further, based on maps (CETENAL, Etzatlán and Tequila sheets, 1:50,000, 1973), created a hypothetical map involving all the flat land that once was occupied by a larger Lago de Magdalena and its environs (fig. 16) extending northwestward to the village of La Quemada. Brumwell (1939) produced evidence that snakes designated by him as Thamnophis macrostemma (= T. eques ) and probably still does. We found it expedient to camp, during each of our three visits, near the small bridge (fig. 15) over the ledge where we found so many snakes engaged in what, in all probability, was a sexual orgy. All of our material was collected within a half kilometer, virtually a single locality, but from which the amount of variation is extraordinary.

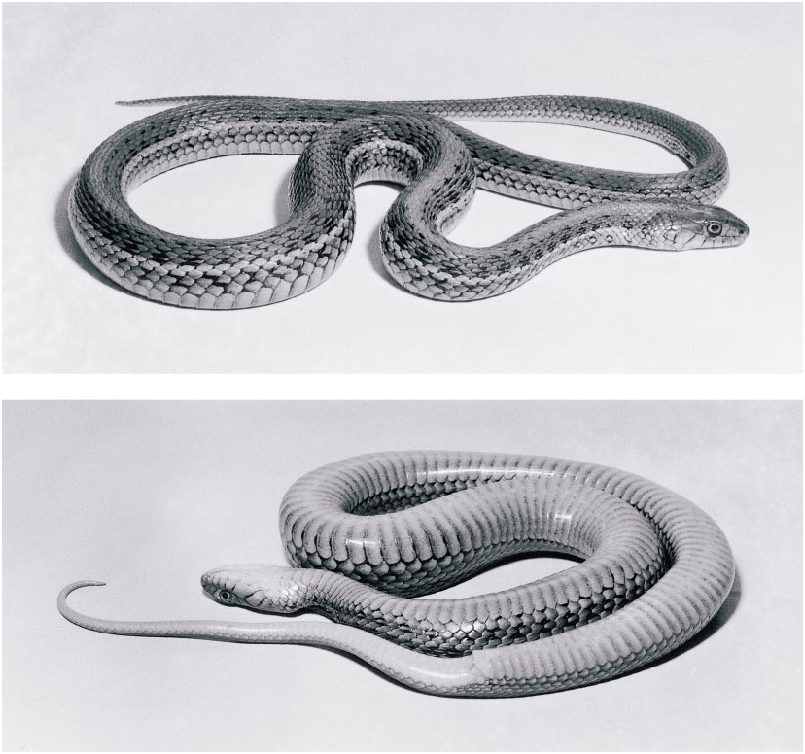

The dorsal coloration may be light or dark, with the paler specimens predominating. In them, the lateral ground color between the dark side spots is only slightly darker than the coloration of the middorsal stripe, and the two similar colors are not separated by dark pigment (fig. 17, upper). In the dark snakes the lateral coloration is in strong contrast with the stripe (color plate, fig. 18, upper).

The width of the middorsal stripe varies from zero to seven scales. In most specimens three to five scales are involved, but in AMNH 94904 there are seven. A middorsal stripe is lacking in several, including AMNH 94050, 94906, and 94910.

For this unique population of garter snakes I propose the name below.

from La Quemada exhibited the same wide variation in pattern that is evident in the available sample from the recent remnants of the Lago de Magdalena. Apparently, there had been widespread desiccation similar to that exhibited west and north of the nottoodistant Lago de Chapala, as indicated under the text for Thamnophis eques diluvialis . Presumably, the Lago de Magdalena formerly was once much larger than it was early during the 20th century. The elevation of the town of Magdalena is 1380 m above sea level.

Variations in dorsal pattern and coloration are the chief characteristics of the population of Thamnophis eques that inhabited the remnants of the Lago de Magdalena in the 1960s

Thamnophis eques scotti , new subspecies

Figures 14–18 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig

HOLOTYPE: AMNH 96691 View Materials , a female from near Magdalena, Lago de Magdalena , Jalisco, collected July 7, 1965, by James D. Anderson, Robert Giacosie, and Roger Conant. Total length 819 mm, tail length 191 mm, tail/total length = 0.233. The holotype gave birth to 18 young on July 31, 1965.

PARATYPES: Several gravid scotti, in addition to the holotype, bore young after our return to base. Each mother’s number listed below is followed in parentheses by the numbers of her offspring; other numbers are of individual specimens: AMNH 87496–87529 View Materials , 94048 View Materials , 94049 View Materials , 94050 View Materials (brood 94051–94058), 94059 (brood 94060–94077), 94078 (brood 94079 –94091 removed by dissection), 94902–94923, 96691 (brood 96692–96709), 96710 (brood 96711–96726) .

ETYMOLOGY: Named for Norman J. Scott, Jr., who might have been a coauthor of this paper if his superiors had permitted him to remain in Albuquerque. A few years ago, he visited several of the lakes of Mexico’s trans volcanic belt and confirmed for me that the snakes were still actively present.

DIAGNOSIS: A large, usually threestriped garter snake, but subject to wide variation. A majority, in life, were relatively pale in coloration, with the ground color between the lateral spots only slightly darker than that of the middorsal stripe. Others were dark, with the body color in strong contrast with the central stripe. The latter normally involves three to five rows of scales, but it may vary from zero to seven scales wide. Pale parietal spots are tiny or absent. No dark line paralleling each side of the pale middorsal stripe as in T. e. carmenensis. The tail spine is usually short and not part of a long scale as in many forms of T. eques .

DESCRIPTION OF THE HOLOTYPE: In its scutellation this specimen agrees with The Species Model, except as follows: The postoculars are 4 instead of 3, with the lowermost on each side extending slightly beneath the eye. A small scale is wedged between the temporals and the parietal, larger on the left than on the right.

Scale rows 211917, reducing to 19 by the loss of row 5 at the level of ventral 82 on the left and ventral 78 on the right. Reducing again to 17 by the loss of row 4 at the level of ventral 105 on the left and ventral 103 on the right. Total ventrals 150; subcaudals 73. Tip of tail bluntly pointed. Apical pits present, but difficult to find in this longpreserved specimen. Total length 819 mm, tail length 191 mm, tail/total length = 0.233. A summary of scale counts for the entire cataloged sample from the Lago de Magdalena is in table 5. An exceptionally large number of wildcaught specimens have incomplete tails.

This is a ‘‘blonde’’ snake and a good example of the way I remember a majority of the specimens of scotti in life. It may be described as follows: Dorsal coloration yellowish brown, middorsal stripe 3 scales wide and a little paler than ground color between stripes. Lateral stripes pale greenish gray on scale rows 3 and 4 anteriorly, rows 2 and 3 posteriorly. An irregular, relatively inconspicuous double row of black spots between the dorsal and lateral stripes; a similar row on scales of first row. Top of head medium brown with several slightly darker, scarcely visible, more or less longitudinal streaks. Pale parietal spots lacking.

Anterior edge of each ventral scute marked with stippled pale gray; posterior part of each ventral pale greenish gray. Posterior threefourths of the ventrals bear pale yellow spots or streaks at the center of their anterior edges that collectively suggest a narrow intermittent yellow midventral line.

Supralabials pale gray. Infralabials, except along or near sutures, yellow. Chin, throat, anal plate, and underside of tail also yellow, unmarked.

VARIATION AMONG THE NEONATES: Total lengths of 18 neonates born in captivity to the holotype ( AMNH 96691 View Materials ) on July 31, 1965, varied from 193 to 232 mm, mean 220.6— 12 males 216–232 mm, mean 225.6; 6 females 193–222 mm, mean 210.8. Tail/ total length in males 0.244 –0.255, mean 0.248; in females 0.229 –0.243, mean 0.235.

A careful inspection of the 18 neonates revealed that they collectively bridged almost the entire range of color and pattern variation in the large adult sample of scotti available. In the latter, the width of the middorsal stripe normally varies from one to five scales (a few have no stripe and one has such a broad stripe that it measures almost seven scales wide). In the neonates the central stripe varies from one to five scales wide regardless of sex. The paired yellowish parietal spots are tiny or missing, as in the adults. Most of the neonates tended to be pale, whereas in others, where the dark spots between the pale lateral stripes are large and dark, they probably would have grown into the dark morph of scotti illustrated in the upper half of the color plate (fig. 18).

The head markings of the neonates differ from those of the adults. The posterior half of the preocular and the anterior half of the postocular are whitish. Immediately posterior to the angle of the jaw the whitish color of the throat extends upward for the height of three scales to form a pale, more or less triangular marking at the rear of the head on each side. Posterior to that marking is a dark bar about three scales wide extending diagonally forward to meet the parietals. Top of head dark brown. A few of the neonates have slight variations from the pattern described.

Among the many snakes collected at the Lago de Magdalena , two of similar size, taken July 7, 1965, and stored in isopropanol rather than ethanol, have retained their coloration and pattern so that they look much as they did in life. They are the holotype ( AMNH 96691 View Materials ) and AMNH 96710 View Materials . They both still agree rather closely with detailed color notes I made on them late in 1965, using the color swatches of Ridgway (1912). The differences involving the two types of preservatives are pronounced. AMNH 96710 View Materials would have been chosen as the type, except that a large part of its tail is missing, probably bitten or broken off by a turtle, heron, or other predator. She bore a litter of 16 young on October 11, 1965, and detailed data from that litter, including weights and color notes recorded shortly after birth, are condensed herewith .

The 16 young of AMNH 96710 include 7 males and 9 females measuring, collectively, 193–217 mm in total length, mean 207.7; weights 2.8–4.0 g, mean 3.4. The head patterns among snakes of this brood are slightly

TABLE 5 Variation in Scutellation and Tail Length Proportions in Thamnophis eques scotti , New Subspecies

different from those of the young born to the holotype (AMNH 96691). The small dark bars immediately posterior to the head run crosswise and are separated from the parietals instead of extending diagonally forward to meet those large scales. Pale parietal spots present, but faint and tiny.

The dorsal ground color in life was medium dark brown (Dresden Brown), and the lateral ground color was yellowish brown (Buckthorn Brown). In some of the young snakes the middorsal stripe matched the darker shade of brown; in others they matched the paler one. Top of head dark brown. Supralabials, preoculars, and lower postoculars bright yellow (Wax Yellow). Chin and throat paler (Massicot Yellow). Un derside of tail even paler (Olive Buff). Venter yellow with a slight greenish tinge (Reed Yellow). Eye: pupil black ringed by orangeyellow; iris brownish olive. Tongue: Coral Red; tips black. Capitalized color names from Ridgway (1912).

VARIATION AMONG THE PARATYPES: In life, most specimens were relatively pale and the middorsal stripe was more or less similar in hue with the coloration between the dark spots on the sides of the body. In essence, they more or less matched the snake portrayed in the upper half of figure 17. Other specimens were dark, with the middorsal stripe in sharp contrast with the adjacent parts of the body as in the upper figure on the color plate (fig. 18).

A recent examination of all the snakes from the Lago de Magdalena revealed many postmortem changes. In a great many there was a darkening, mostly on the sides of the body, but also frequently involving the middorsal stripe. Especially noticeable was a change in the upper labials from a pale gray in some to black in others. In life, the supralabials were usually pale gray to yellowish (figs. 17, 18). Other postmortem changes involved the lower sides of the body. The lateral stripes had become bluish and the two lowermost rows of scales had light centers in dark scales, some black, resulting in continuous rows of light spots. In some that had lost many scales (the stratum corneum), the sides of the body were pale in color.

Both in the field and when snakes were euthanized after periods of captivity they were thoroughly injected with formalin for hardening. Almost all were then transferred to ethanol, in which preservative they darkened, some of them considerably.

REPRODUCTION: The gravid females we took home with us gave birth to their young, and some of the mothers that were retained alive with captive males had additional offspring a year or more later.

Five broods of young were born in captivity from females collected at Magdalena. Dates of collection were July 7 and August 18. Dates of birth ranged from July 31 to November 10. In the case of the latter date, the apparently fullterm young were removed by dissection when the mother, held captive in my office at the Philadelphia Zoo, was euthanized after she strained for several hours but was unable to extrude her young.

The number of young in a brood varied from 8 to 18. The total lengths of the offspring were from 186 to 251 mm. Not all the young were weighed, but those that were varied from 2.3 to 5.5 g. Scale counts for most of these are summarized separately in table 5.

One large heavybodied female, AMNH 94050, collected August 18, 1964, near Magdalena had an unusual record. From her impregnation in the wild she had eight young (AMNH 94051–94058) on September 1, 1964. She was caged with a male and she bore 14 additional young on July 18, 1967. Because so many other neonates were available, the 14 were not tagged, but they were preserved with their dam. She bore another litter on July 26, 1968, that was discarded. The male died during June 1968. On October 17, 1969, the female passed three young, one alive and two full term but dead, probably a case of delayed fertilization, at one time called amphigonia retardata. The female died on October 24, 1971, after living in excess of seven years in captivity. More than half of her tail was missing and she bore a large, wellhealed, protuberant rounded scar 30 mm in diameter and 13 mm in depth on the right side of her neck, less than a head length posterior to the angle of the jaws.

REMARKS

Synchronization in time was absent. The thought often occurred to me, however, about what an ideal place the half hectare or so where scotti was so abundant in the early 1960s would have been for presentday sophisticated studies. They might have includ ed the implantation of hightech devices capable of recording a variety of data.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |