Chulacarus elegans, Fuangarworn, Marut, Lekprayoon, Chariya & Butcher, Buntika Areekul, 2016

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4061.5.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A45AF66A-ACDF-4F36-8B3B-0E4B1C4924A7 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6058356 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/A30E115D-B21E-9862-F6DC-FAAB9081BF2F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Chulacarus elegans |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Chulacarus elegans n. sp.

( Figs. 1–14 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 View FIGURE 12 View FIGURE 13 View FIGURE 14 )

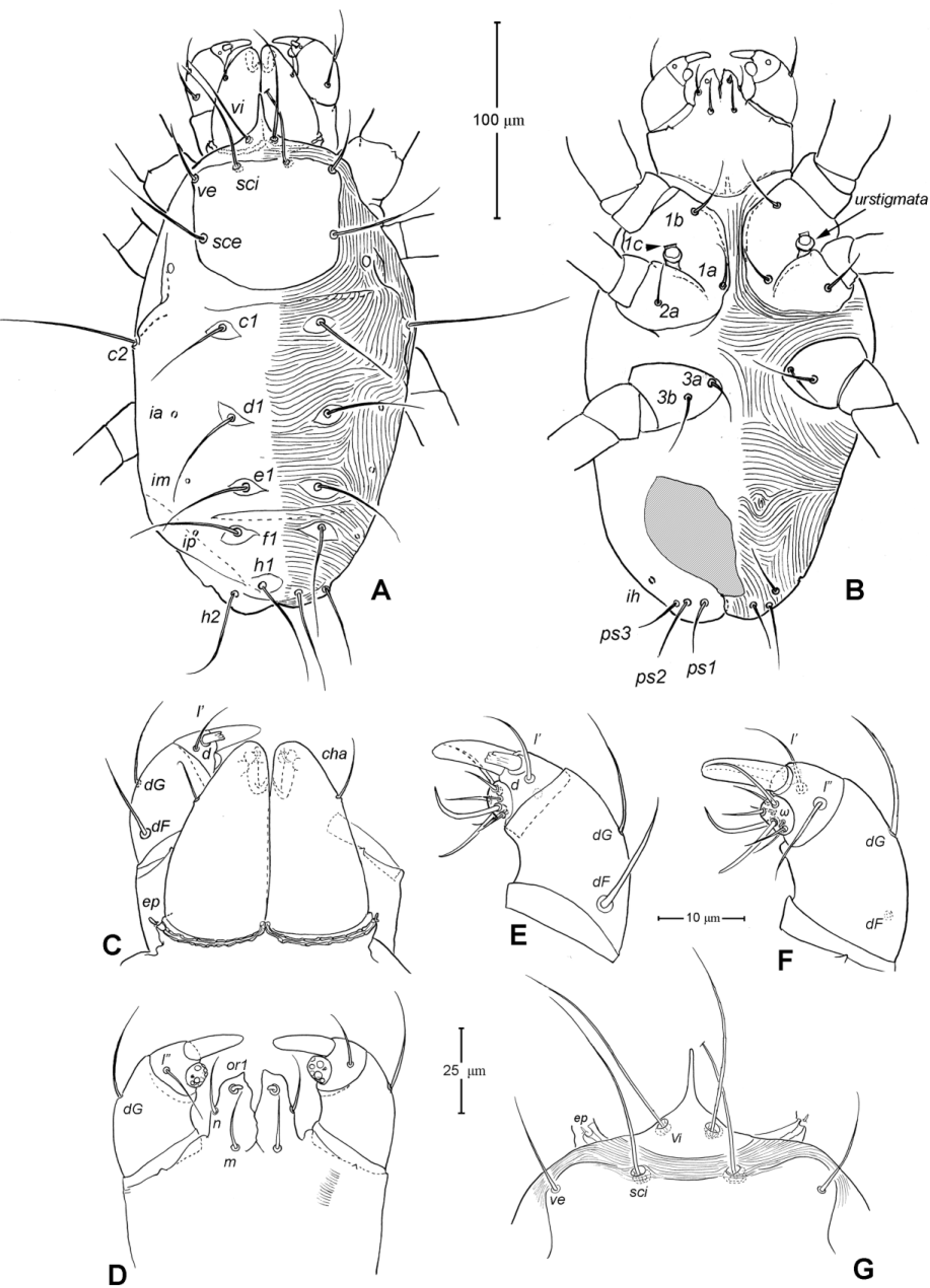

Adult Female. Color in alcohol pale yellow. Body length (from apex of naso to posterior end of idiosoma; n =5) 405 (370–450). Body width (greatest width at the level of seta c2) 230 (215–245). Idiosoma ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A) ovoid, ca. two times longer than wide, posterior end rounded.

Gnathosoma ( Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 A, 3). Subcapitulum 121 (115–125) long, 139 (140–150) wide; integument striate; subapically on lateral lips with 2 pairs of short thickened and truncated adoral setae (or1 and or2); subcapitular setae n and m simple, seta n located laterally, seta m located ventrally. Ventral lip (labium) present, short triangular; dorsal lip (labrum) triangular in outline, appearing smooth. Supracoxal seta ep small, rod-like. Palp ( Figs. 3 View FIGURE 3 A, D– E) 4-segmented: trochanter very short, femur and genu fused, 60 (55–65) long, 40 (35–45) wide, with 2 barbed filiform setae (dF and dG); tibia with well developed terminal claw, 2 simple setae (l’ and l”) and 1 thickened blunt seta d (= accessory claw); tarsus reduced, knob-like, situated at subterminal position on tibia (forming a ‘thumbclaw’ complex structure), with 8 setae (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) and one short rod-like solenidion (ω); setae 3 and 5 eupathidial. Chelicera ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B–C) 104 (100–110) long, greatest width at shaft base 47 (45–50), and relatively flat; cheliceral seta cha short and simple, located laterally; seta chb thicker, about twice as long as cha, located more anterior-medially; movable digit hook-like; fixed digit absent, replaced by membranous hyaline process through which a short slender styliform process pierces out ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 C). Two pairs of stigmatic openings present: paraxial stigmata (stπ), between base of chelicerae and produced on to linear, segmented peritremes; peritremes, not elevated, transversely passing on dorsum of cheliceral bases and ending at their lateral face; subcheliceral stigmata (sti) at normal position, opening as simple broad slit and leading to tracheal trunk which narrows to join tracheal trunk of stπ ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A–B), forming X-shaped tracheal system.

Idiosoma ( Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2 View FIGURE 2 A). Integument with striation as illustrated; dorsally, with prodorsal shield, 102 (100–105) long and 119 (105–130) wide, smooth, subrectangular in shape, anterior margin concaved. Naso present, surface smooth and separated from prodorsal shield by narrow striae ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C). Four pairs of prodorsal setae (vi, ve, sci and sce) of which 2 pairs (vi and sci) trichobothrial; all these setae filiform and finely barbed. Trichobothrium vi situated posterior to naso, its bothridium with (2–3) or without radial chambers ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C). Trichobothrium sci, 84 (80–90) long, situated on anterior margin of prodorsal shield, usually on striae, its bothridium larger than that of vi, and with 3–5 radial chambers ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C). Seta ve 50 (40–55) long, situated on anterior corner of shield. Seta sce 105 (100–110) long, situated near halfway of lateral margin of shield. One pair of small lens-like eyes present on membrane postero-lateral to sce ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A, ocellus); a pair of internal spots present, posterior to lateral eyes; median eye under naso not observed.

With 13 pairs of hysterosomal setae (c1, c2, d1, e1, f1, h1, h2, ps1, ps2, ps3, ad1, ad2 and ad3), all filiform, finely barbed and on small platelets. Their lengths: c1 63 (55 –75), c2 108 (100–115), d1 67 (60–75), e1 68 (65– 75), f1 75 (70–85), h1 69 (65–75), h2 64 (60–75), ps1 67 (65–70), ps2 53 (50–60), ps3 45 (40–55), ad1 37 (35–40), ad2 41 (40–45), ad3 39 (40–45). With 4 pairs of lyrifissures (ia, im, ip and ih) at normal position ( Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2 View FIGURE 2 A). Anal opening terminal, anal valve devoid of setae.

Epimeral region. Coxal plates smooth; membrane striated ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 B). Coxal plates I and II contiguous on either side but separated medially by soft membrane as are coxal plates III and IV. Coxal plates II and III separated by transverse band of sejugal cuticle. Apodeme 1 (apo.1) triangular in form, well developed and deeper than apodemes 2–4. Coxal setae slender and finely barbed; coxal setation: 4–2–3–2; setae 1b, 1d longest.

Genital region ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 B). Genital opening 107 (100–115) long, with well defined genital valve, 6 or 7 pairs of genital setae (ca. 20–25) arranged in longitudinal row, and 3 or 4 pairs of aggenital setae (ca. 25–27). Ovipositor ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 D) present usually with 5 pairs of eugenital setae: eug1–5 on superimposed tubercle; eug1–4 (about 8–12 long) widely spaced, sometimes eug4 absent; eug5 (about 5 long) coupled to its pair. Genital papillae small, hard to discern, 8–10 pairs, presumably multiplied from typical three pairs of genital papillae (Va, V m and Vp); setae k2 and k3 present, seta k1 not discernable ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 D).

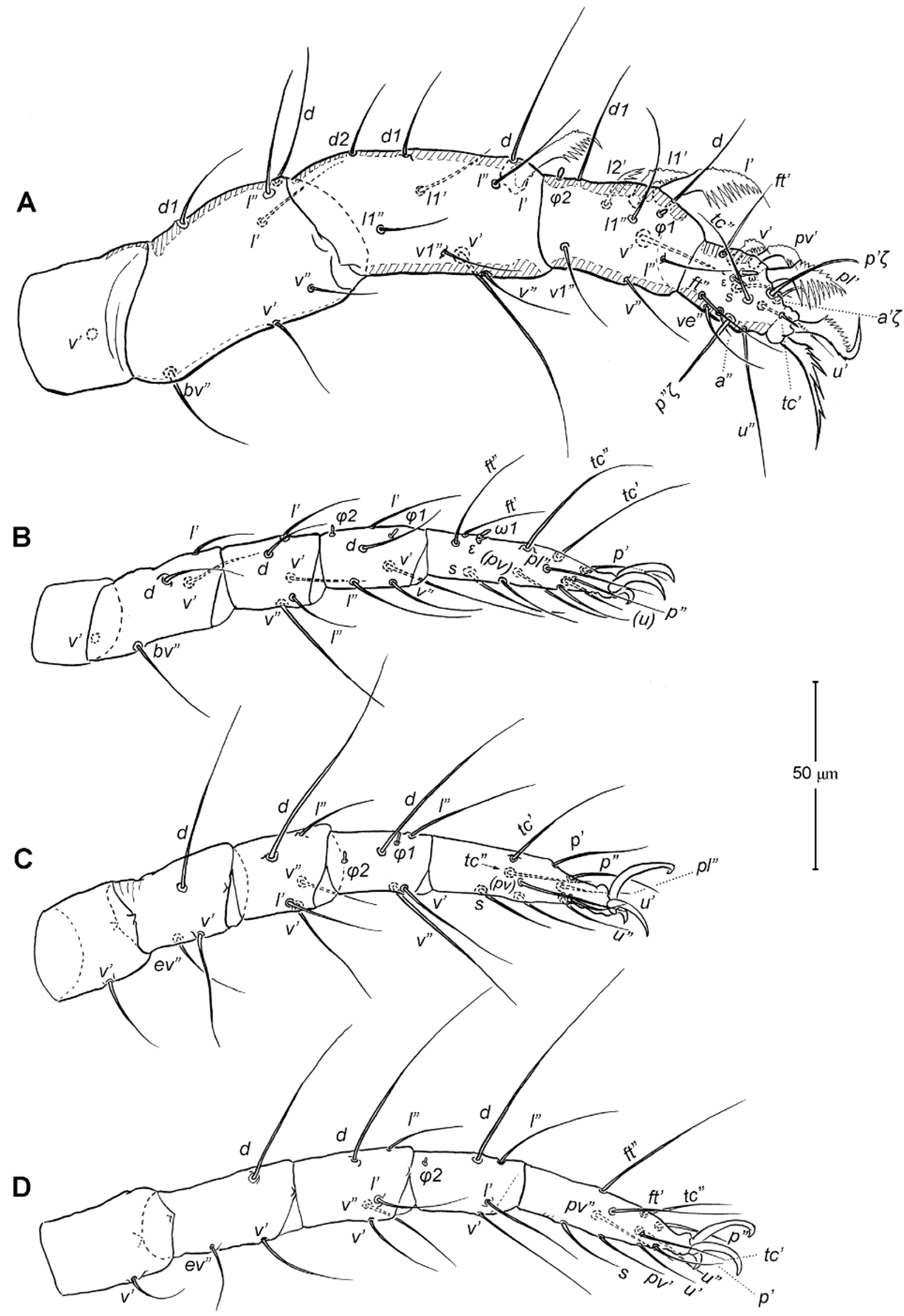

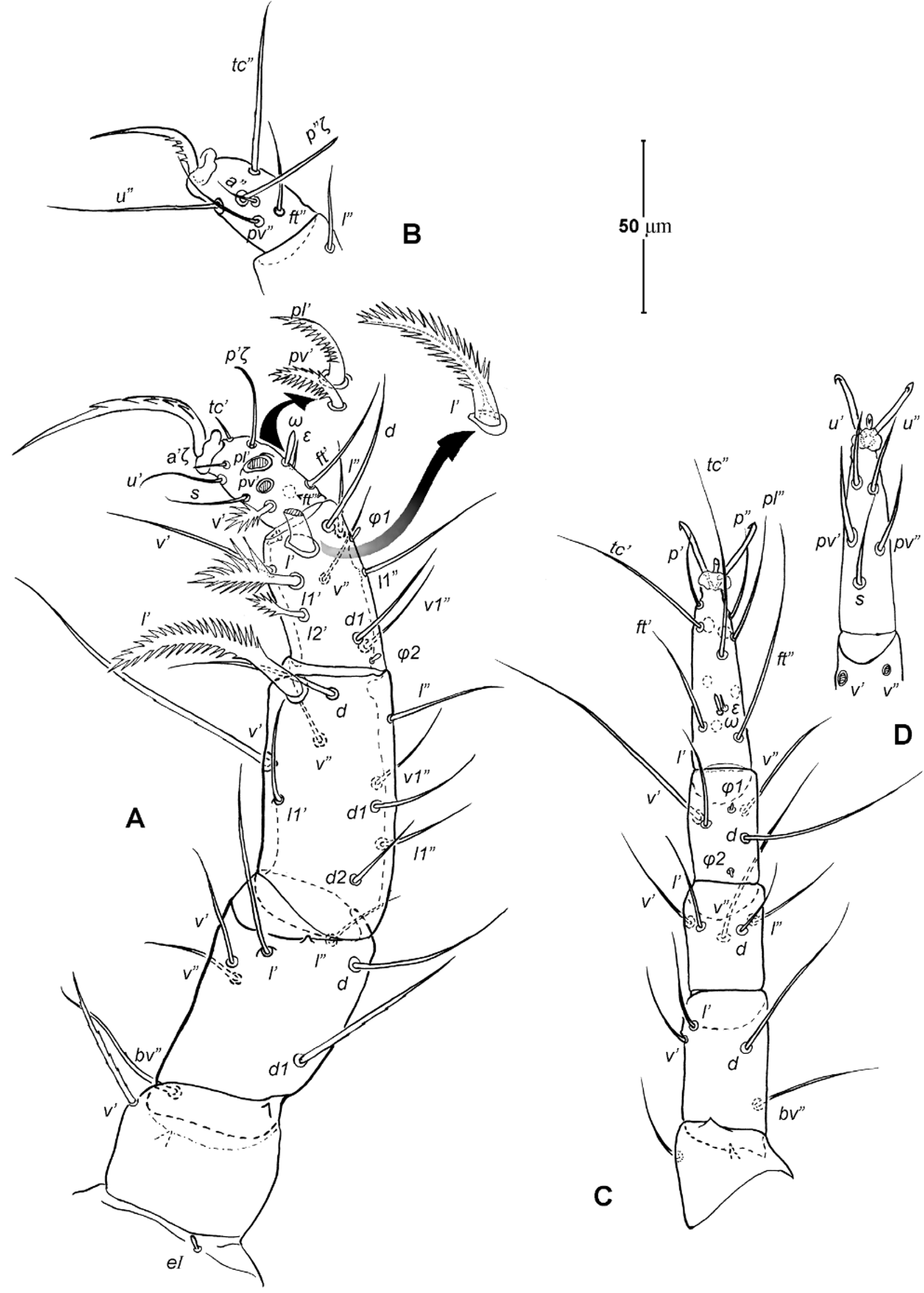

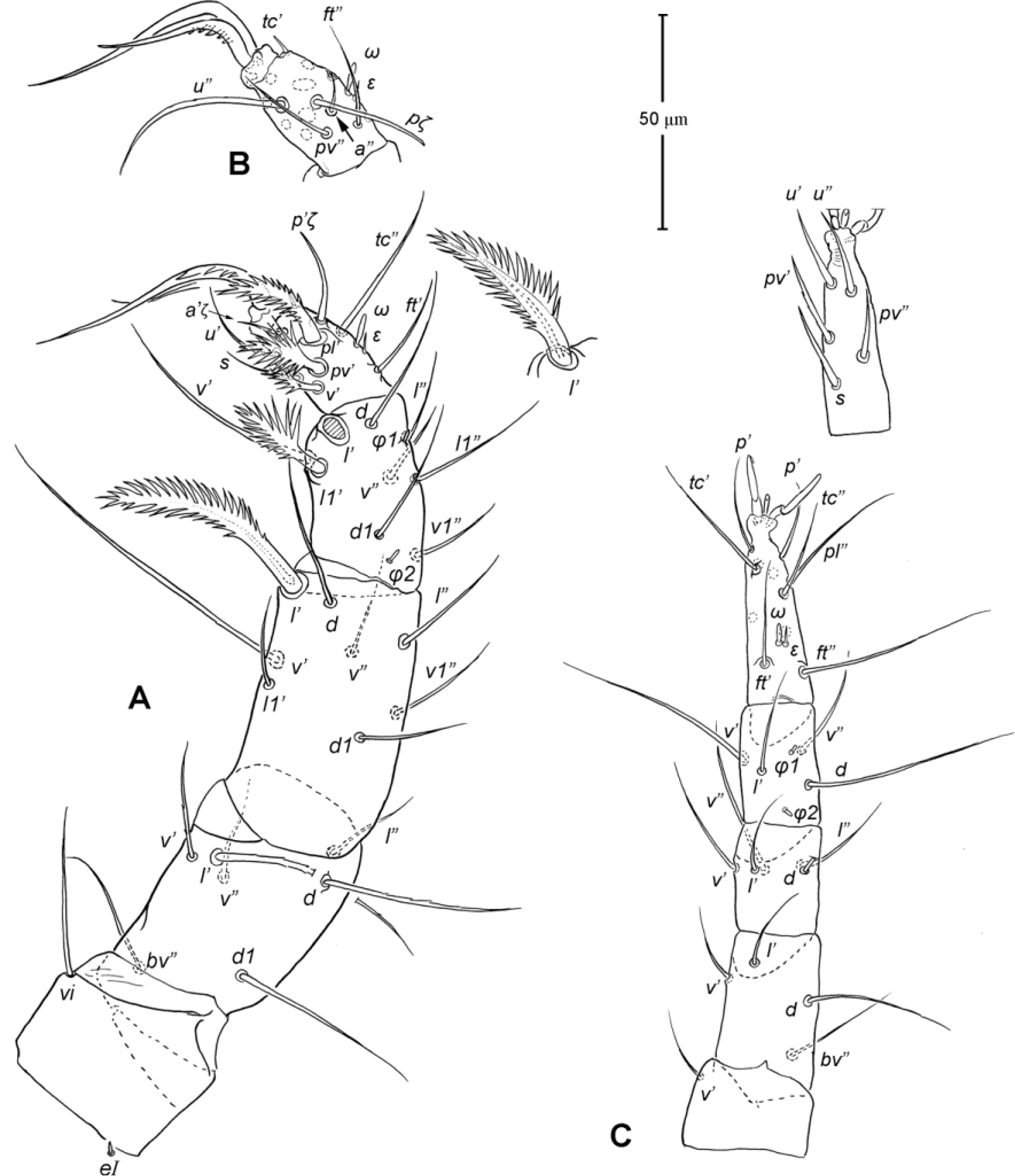

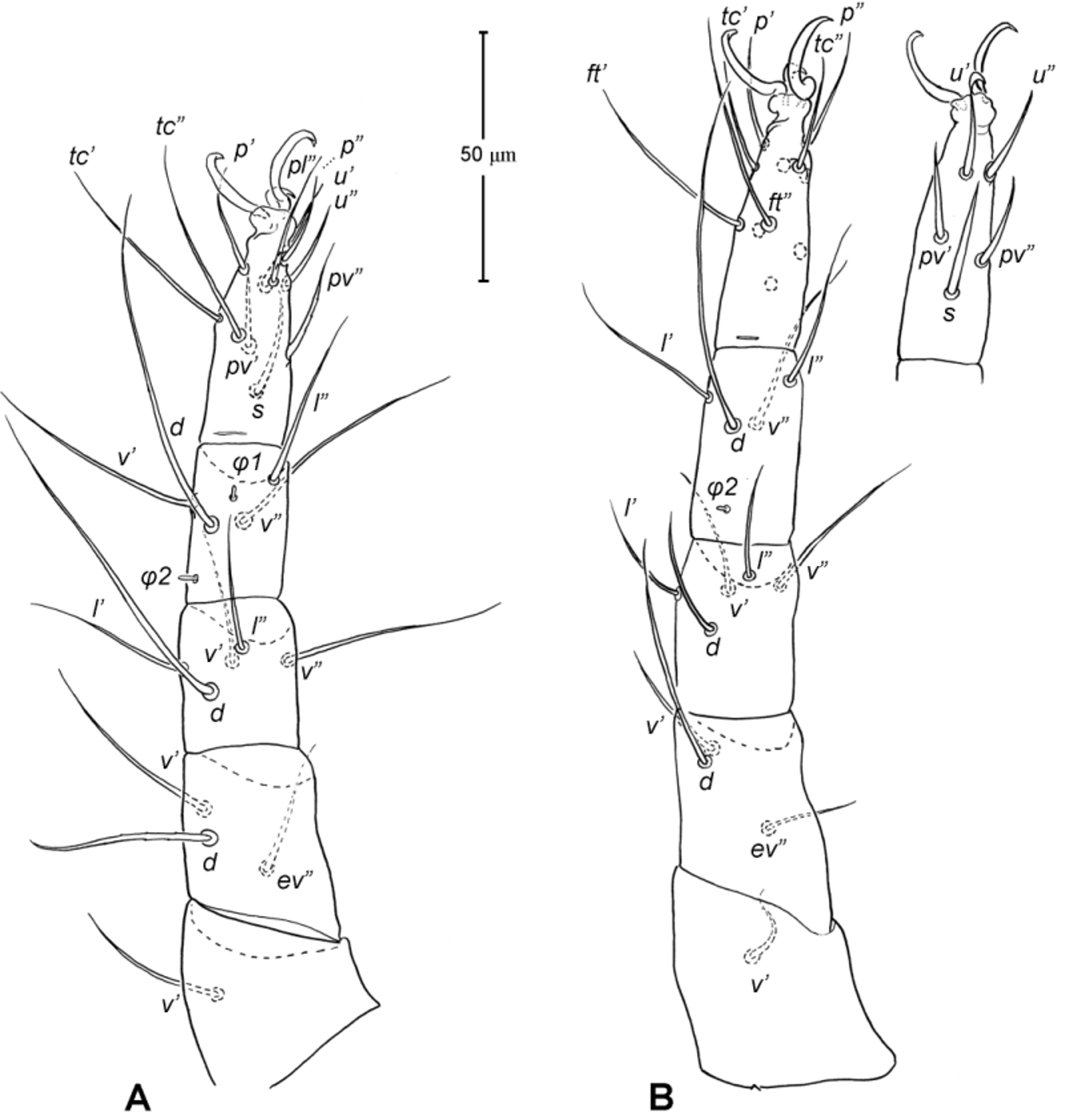

Legs ( Figs. 5–6 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 ). Integument smooth. All legs shorter than idiosoma. Leg I raptorial, relatively large and robust, about two times wider than other legs; hinge joints on antiaxial side and extensive arthrodial membrane on paraxial face. All femora and tarsi undivided. Leg lengths (from base of trochanter to distal end of tarsus, excluding apotele): I 239 (225–250), II 194 (175–210), III 204 (190–215) and IV 235 (220–245). Supracoxal seta e1 short rod-like. Setation of legs I–IV (famulus included, solenidia in brackets): trochanters 1-1-1-1, femora 6-4-3-3, genua 10-5-5-5, tibiae 10 (2)-4/5(2)-4(2)-4(1), and tarsi 16(1)-13(1)-9/10-11. For leg I, tarsus shorter than tibia, and genu longest. Most leg setae filiform and finely barbed, except some setae on leg I: genual seta l’, tibial setae l’, l1’ and l2’ and tarsal setae pl’, pv’ and v’, being bipectinate ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A). Solenidion ω1 of tarsus I rod-like, situated laterally on segment and coupled with famulus ε, which is spiniform and birefringent. Solenidia φ1 and φ2 on tibiae I–III rod-like; φ1 distal while φ2 proximal to middle of segment. Solenidion ω1 of tarsi II short, rod-like, also coupled with famulus ε. Solenidion φ2 of tibia IV short, rod-like, situated proximal to middle of segment. Pretarsus I with unequal claws, adaxial claw longer, each serrated along basal half of adaxial face ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A), i.e. unipectinate; empodium absent; pretarsi II–IV with normal claws, smooth, and claw-like empodium.

Male. Unknown.

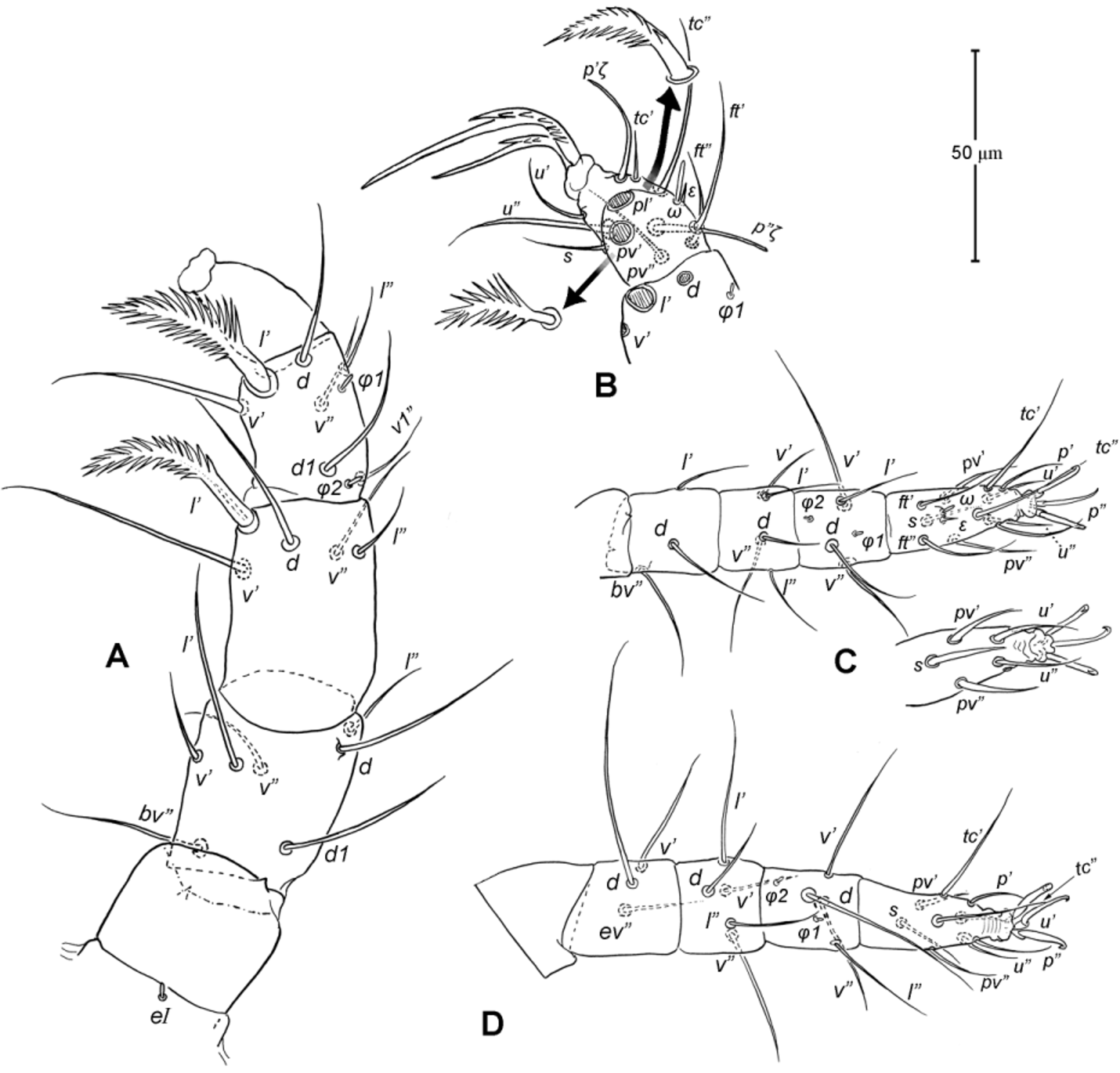

Ontogeny ( Figs. 7–14 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 View FIGURE 12 View FIGURE 13 View FIGURE 14 ). Size. Larva (n =1, Figs. 7–8 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 ): body length (including gnathosoma) 315 long, 195 wide. Protonymph (n =2, Figs. 9–11 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 ) 370 (350–390) long, 180 (170–195) wide. Deutonymph unknown (among the specimens collected, deutonymphs were absent; the individuals identified as tritonymph (below) are based on their size which is rather close to that of adults, and on a similar number of genital papillae). Tritonymph (n =2, Figs. 12– 14 View FIGURE 12 View FIGURE 13 View FIGURE 14 ) 488 (475–500) long, 233 (225–240) wide.

Gnathosoma. Similar to adult except chelicera with 1 simple seta cha in larva ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 C), 2 in protonymph (chb added) and later instars; lateral lips with 1 pair of adoral setae of adult form in larva, 2 pairs in protonymph (or2 added).

Idiosoma. Similar to adult except naso distinctly pointed in larva and nymphs; 10 pairs dorsal hysterosomal setae in larva (c1, c2, d1, e1, f1, h1, h2, ps1, ps2 and ps3), 13 pairs in protonymph (ad1–3 added) and later instars. Lengths of dorsal setae: larva, vi 60, ve 33, sci 63, sce 65, c1 70, c2 80, d1 50, e1 50, f1 57, h1 53, h2 50, ps1 28, ps2 27 and ps3 25; protonymph: vi 55 (50–60), ve 38 (35–40), sci 67 (65–70), sce 78 (75–80), c1 53 (50–55), c2 90 (85–95), d1 55 (50–60), e1 50 (50), f1 53 (50–55), h1 50 (50), h2 53 (50–55), ps1 30 (30), ps2 30 (30), ps3 33 (30– 35), ad1 23 (20–25), ad2 23 (20–25) and ad3 23 (20–25); tritonymph: vi 73 (70–75), ve 45 (45), sci 70 (65–75), sce 95 (90–100), c1 60 (55–65), c2 88 (88), d1 65 (60–70), e1 60 (55–65), f1 65 (60–70), h1 68 (65–70), h2 ca. 55, ps1 ca. 33, ps2 40 (40), ps3 35, ad1 30 (30), ad2 33 (30–35), and ad3 30 (30).

Epimeral region. Similar to adult except coxal setae formula 3- 1-2 in larva ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 B); urstigmata present between coxae I and II, having circular head and covered by scale of coxa I (= scaliform seta 1c); 3-1-3-0 in protonymph, seta 1c becoming setiform and 3c added; 4-2-3- 2 in tritonymph (1d, 2b, 4a, 4b added but their origin, deutonymphal or tritonymphal, uncertain). Homology of coxal setae depicted in Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 B, 9B, 12B.

Genital region. Genital opening absent in larva, present in later instars; genital setae absent in larva, 1 pair (g) present in protonymph, ca. 15 long, and tritonymph, ca. 18 long. Aggenital setae absent in larva and protonymph; 2 pairs (ag1–2) present in tritonymph, ca. 20–23 long. Genital papillae present in protonymph (but exact numbers could not be determined due to their extremely small size and hard to discern); and 7–8 pairs in tritonymph ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 D).

Legs. Generally similar to adult in form, larva with 3 pairs of legs, 4 pairs in later instars. Larval pretarsi II–III, and protonymphal pretarsus IV tridactyle, with smooth claws and slender, claw-like empodium, which becomes smaller in later instars. Lengths of legs: larva, leg I 125, leg II 115, leg III 128; protonymph, I 165 (160–170), II 128 (125–130), III 143 (140–145) and IV 143 (140–150); tritonymph, I 200 (200), II 150 (150), III 173 (170–175) and IV 188 (185–190). Setation of legs I–III (famulus included, solenidia in brackets) in larva: trochanters 0-0-0, femora 6-3-3, genua 5-5-5, tibiae 7(2)-4(2)-4(2), and tarsi 13(1)-12(1)-9; on leg I, genual seta l’, tibial seta l’, tarsal setae pl’ and pv’ strongly thickened and bipectinate ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 A–B); tarsal setae p’ and p” eupathidial, tc’ coupled with p’ (their alveoli touch). Protonymph: trochanters 1-1-1-0; femora 6-3-3-0; genua 7-5-5-0; tibiae 8(2)-4(2)- 4(2)-0 and tarsi 15(1)-12(1)-9-7; on tarsus I, a’ added as eupathidion, tc’ dissociated from eupathidion p’ and becoming more distal; small seta a” added and coupled with eupathidion p” (their alveoli touch). Tritonymph: trochanter 1-1-1-1; femora 7-4-3-3; genua 8-5-5-5; tibiae 9(2)-4(2)-4(2)-4(1); tarsi 16(1)-13(1)-10-11. Homology of leg setae depicted in Figs. 8 View FIGURE 8 , 10–11 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 , 13–14 View FIGURE 13 View FIGURE 14 . Addition of leg setae during development summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Ontogeny of the leg setae of Chulacarus elegans n. sp. 1 1 Placement indicates instar of 1st appearance; dash indicates no change and parentheses indicates a given pair. Abbreviations: La, larva; Pn, protonymph; Dn, deutonymph; Tn, tritonymph; Ad, adult.

2 The deutonymphs are not available, so setal and solenidial origin in tritonymph are uncertain as to whether they are deuto- or tritonymphal in origin.

Material examined. Female holotype (slide mounted): THAILAND, Tak Prov., Srisawad Dist., Sam-Ngoa Subdist., RSPG Forest Reserves at Bhumibol Dam (17°14'46.87"N, 98°59'45.66"E); ex. forest litter; 2-III-2008; leg. M. Fuangarworn (Field No. MF2008-9). Six female paratypes: (2 slide-mounted and 4 in alcohol); One female paratype (slide-mounted), same data as holotype except on 8-IX-2007 and leg. Ekachai Jirathitikul. One female paratype (slide-mounted); Sakaerat Biosphere Reserve, Pakthongchai District, Nakorn-Ratchasima Province; ex. Soil; 19-I-1975; leg. Samrit. Three tritonymphs (all slide-mounted), four protonymphs (2 slide-mounted and 2 in alcohol) and one larva (slide-mounted) with same data as holotype. Most of type materials are deposited in the Acarology collection of the Chulalongkorn University Museum of Natural History, Bangkok, Thailand. One female paratype will be deposited in the Acarology Collection of the Ohio State University, Columbus, USA.

Etymology. The specific epithet is from the Latin elegans , meaning ‘elegant’.

Distribution. Known only from Thailand: Nakorn-Ratchasima and Tak Provinces ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 C).

Morphological notes. The selected characters of Chulacarus elegans that are unusual or relevant for further comparisons in the next section are discussed below. Most comparisons are made against the members of Anystae, in which the new taxon probably belongs and, unless other sources are indicated, are based on the original descriptions, reviewed and revisionary studies (below), along with overviews by Walter et al. (2009) and unpublished observations by the authors on the representatives of each family collected in Thailand.

Adamystidae : Ueckermann (1989); Fuangarworn and Lekprayoon (2010); Fuangarworn et al. (2012); Fernandez et al. (2014); Coineau et al. (2006); unpublished observations on Adamystis sp., adults, deutonymphs and tritonymphs.

Anystidae : Grandjean (1943); Meyer and Ueckermann (1987); Otto (1992, 1999a, 1999b, 1999c, 2000); unpublished observations on Anystis sp., all active stages, Erythracarus sp., all active stages, Tarsotomus sp., adults.

Caeculidae : Coineau (1974a and references therein, 1974b); Otto (1993); Mangová et al. (2014); Ott and Ott (2014); Taylor et al. (2013); Taylor (2014); Fuangarworn and Butcher (2015b); unpublished observations on Microcaeculus sp., all juveniles stages.

Paratydeidae : Theron et al. (1969); Kuznetzov (1974); Seeman and Walter (1999); Dönel et al. (2012); Khanjani et al. (2014); unpublished observations on Tanytydeus sp., all active stages, Scolotydaeus sp., adult.

Pomerantziidae : Fan and Chen (2005); Bochkov and Walter (2007); unpublished observations on Pomerantzia sp., all active stages.

Pseudocheylidae : Baker and Atyeo (1964); Van Dis and Ueckermann (1991); Ueckermann and Khanjani (2004); Novaei-Bonab et al. (2011); Bagheri et al. (2013); Skvarla et al. (2013); Khanjani et al. (2014); Khaustov and Tolstikov (2015); Fuangarworn and Butcher (2015a).

Stigmocheylidae: Bochkov (2008); unpublished observations on Stigmocheylus sp., all post-larval stages.

Teneriffiidae : Ehara (1965); Strandtmann (1965); Shiba and Furukawa (1975); McDaniel et al. (1976); Luxton (1993); Judson (1994, 1995); Ueckermann and Khanjani (2002); Khanjani et al. (2011); Bernardi et al. (2012); Khanjani et al. (2013); unpublished observations on Austroteneriffia sp., all active stages.

1. Ventral lip. The presence of a ventral lip (labium) in Chulacarus elegans ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A) is considered retention of a plesiomorphic state exhibited in the early derivative lineages of Acariformes ( Lindquist & Palacios-Vargas 1991; Jesionowska 2003). Among the members of Anystae, this labial structure is known only in Adamystidae ( Coineau & Naudo 1986) and the erythracarine Anystidae ( Otto 1999a; pers. obs.).

2. Adoral setae. Regardless of their lengths, the adoral setae are usually similar in form with the subcapitular setae. In Chulacarus elegans , the adoral setae are thickened and truncated opposed to the slender subcapitular setae ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A). This form of the adoral setae is also found in all known species of Teneriffiidae . The specialization of these setae is present in Pseudocheylidae (they are minute, spine-like) and Pomerantziidae (spine-like inserted without alveolus, apparently immobile). Other members of Anystae (i.e. Adamystidae , Anystidae , Caeculidae , Paratydeidae , and Stigmocheylidae) have the adoral setae similar in shape to the subcapitular setae.

3. Cheliceral stylet. Judson (1994, 1995) reported the presence of a cuticular stylet, probably representing a duct of the cheliceral glands ( Judson 1994), on the hyaline process of the chelicerae in the teneriffiid genera Neoteneriffiola and Austroteneriffia . Chulacarus elegans has such a stylet in the similar form: slender, sigmoid and pointing downward; and its tip protrudes from the hyaline process ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 C). However, there are no records of its absence or presence in other members of Anystae, but based on our preliminary observations this cheliceral stylet is absent in most of the representatives of each family examined. An exception is the Pseudocheylidae which possess a similar structure but its tip is remarkably expanded and not protruded from the hyaline process ( Fuangarworn & Butcher 2015a). The genus Adamystis (Adamystidae) has a forked process at the cheliceral tip; it is interpreted as a remnant of the fixed-digit.

4. Cheliceral setae. Primitively, the chelicerae bear two setae: cha and chb, and both are larval. Chulacarus elegans has two cheliceral setae but they are developmentally unusual: only cha first forms in the larva, chb is then added in the protonymph ( Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 C, 9C). The delay of chb has not been previously reported in other families of Anystae having two cheliceral setae.

5. Palptibial claws. In addition to the terminal ‘thumb’ claw, Chulacarus elegans has one subterminal accessory claw on the palptibia and this accessory claw is larval ( Figs. 3 View FIGURE 3 D, 7E–F). This developmental aspect among Anystae whose juveniles are described is known in Pomerantziidae , and possibly Stigmocheylidae (larva unknown). Teneriffiidae and Pseudocheylidae also have larval, but two, accessory claws. In the anystid subfamily Anystinae, the two accessory claws are added in the protonymphs ( Grandjean 1943; Mayer & Ueckermann 1987), thus are developmentally unique, and these two accessory claws do not seem homologous to those of other Anystae. The accessory claw(s), once formed, are constant in shape throughout ontogeny of the aforementioned taxa. However, in the erythacarine Anystidae , the development of the accessory claw(s) shows at least two variations (based on 4 of 10 recognized genera): being slender setae in larvae and then transformed to spine-like setae (=accessory claw) in nymphs and adults ( Pedidromus , Tarsotomus ; Otto 1999c, 2000), or being spine-like ( Chaussieria ; or feather-like in Erythracarus ; Otto 1999a, 1999b) in larvae and remaining so until the adult. In Caeculidae , the palptibia has 1 or 2 accessory claw(s) which are often indistinct, i.e. they are often in an intermediate form between normal setae and spine-like setae, especially the proximal member. However, these setae are clearly larval ( Coineau 1974a, 1967) and then, like some erythacarine Anystidae , transform more or less into the form of the accessory claw during ontogeny (per. obs.). Outside Anystae, it is worth noting that most members of Tarsocheylidae , a basal group within Heterostigmata, have apparently two larval accessory setae, but these are fused, giving a bifid appearance ( Lindquist 1976; Khaustov 2015).

6. Peritremes. The presence of the peritremes is hypothesized to be one of the synapomorphies of the ‘Anystina-Eleutherengona complex’ ( Lindquist 1976; Walter et al. 2009). Within this group, the shapes of the peritremes vary greatly, or are even lost, and are usually the diagnostic characters at familial or generic level. In Anystae, the peritremes are usually linear, ‘segmented’ (an impression of its alveolae ornamentations), transversely lying at the bases of the chelicerae; their distal end may be emergent ( Anystidae , Paratydeidae , some Pseudocheylidae , some Teneriffiidae , and Stigmocheylidae) or not ( Adamystidae , Caeculidae , Pomerantziidae , and Chulacarus, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B). The peritremes may be produced onto the anterior corners of the idiosoma as in some Pseudocheylidae and most Teneriffiidae .

7. Stigmata and tracheae. According Pepato & Klimov (2015), the presence of the dorsal stigmata (stπ; = neostigmata), in addition to the sub-cheliceral stigmata, is apomorphic relative to the plesiomorphic presence of only the sub-cheliceral stigmata found in Labidostommatidae , the basal prostigmatic clade in their analysis. Based on a few existing studies, the tracheal trunk of the dorsal stigmata (which are located at the inter-cheliceral position) usually converge with those from the sub-cheliceral stigmata and exhibit various connections with the latter: (i) running along each other without fusion as found in the tydeid genus Tydaeolus (Grandjean 1938a; Judson 1994); or (ii) fused to the latter into a single tracheal trunk, giving a ‘Y-shaped’ appearance as found in the bdellid genera Odontoscirus and Neomolgus (Grandjean 1938b; Judson 1994), or (iii) fused to the latter but then diverged, giving an ‘X-shaped’ tracheal system as found in the teneriffiid Neoteneriffiola coineaui Judson , Tetranychidae ( Andre & Remacle 1984; Judson 1994), and in Chulacarus elegans ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 B). In addition, there is perhaps an intermediate type of tracheal system as found in Caeculidae : the two stigmata (the smaller paraxial one and the larger antiaxial one) are arranged transversally, both in the sub-cheliceral position, and it is only the latter stigma that gives rise to the tracheal trunk. Coineau (1974a) considered that there is only one trachea with two stigmata and interpreted this as representing an intermediate state between having a single trachea with a single stigma (as in Labidostommatidae ) and two trachea with two stigmata (or a Y-shaped trachea; Coineau 1974; M. Judson per. com.). Heterostigmata display another unique variant of stigmata-tracheal system ( Sidorchuk et al. 2015)

8. Naso. The naso is variably expressed across taxa within Anystae. It may be remarkably large, auriculate with distinct ornamentation ( Adamystidae ); well sclerotized and plate-like ( Caeculidae ); narrow and pointed (some Anystidae ); rather broader and short (some Anystidae , Teneriffiidae ); or vestigial or absent (Some erythracarine Anystidae , Stigmocheylidae, Paratydeidae , Pseudocheylidae , Pomerantziidae ). The adults of Chulacarus elegans have the rather broad and short naso ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C); and, ontogenetically, it is relatively longer and pointed in the larvae ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 G) and gradually shortened in the subsequent instars ( Figs. 9 View FIGURE 9 A, 12A). An immature stage with a pointed naso is found at least in the teneriffiid genus Neoteneriffiola ( Bernardi et al. 2012) , but not in the genus Austroteneriffia of same the family ( Khanjani et al. 2013).

9. Lateral Eyes. Among families of Anystae, when the lateral eyes present, there are usually two pairs of which the anterior pair are clearly lens-like while the posterior pairs may be lens-like, or finely striated as in the anystid genus Erythracarus ( Otto 1999a) . The presence of one pair of lateral eyes in Chulacarus elegans is considered unusual. They are lens-like and unusually small, only about an alveolus diameter of the seta sce ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A). The posterior lateral eyes are absent, i.e. there is no change in striation patterns (density) that would indicate such eyes; however, in recently collected specimens, internal spots are evident posterior to the anterior lateral eyes ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A). This condition appears to be similar to that of Pseudocheylidae , having one pair of lens-like lateral eyes (probably anterior ones) but at the anterior corners of the prodorsal shield; the (external) posterior eyes of Pseudocheylidae are absent but a pair of internal spots is evident at its normal position, i.e. near level of the setae sce ( Skvarla et al. 2013; Fuangarworn & Butcher 2015a). Some members of Paratydeidae (Walytydeus tauricus Kuznetzov, 1973 and Scolotydaeus bacillus Berlese, 1910 ) were described as having one pair of lateral eyes but, like Pseudocheylidae , these eyes are situated more anteriorly, close to the level of setae ve (as do the other paratydeids bearing two pairs of eyes). In Adamystidae , one pair of lateral eyes is present in the genus Adamystis , and in one species of Saxidromus , S. delamarei Coineau, 1974 c; the lateral eyes of the former are often associated with the ‘post-ocular bodies’ of unknown function.

10. Urstigmata and genital papillae. The larva of Chulacarus elegans have a pair of urstigmata in a primitive form ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 B): with short stalk, dome headed and covered by a scale (= modified seta 1c) of coxa I ( Baker 1985; Grandjean 1942; Theron & Ryke 1975). This condition is also retained in Pomerantziidae ( Bochkov & Walter 2007) and Paratydeidae ( Theron et al. 1969) . The urstigmata may be variously reduced, being papilla-like with a central pore (as in Caeculidae ), or papilla-like on the anterior-dorsad of coxa II (the anystid mite genus Anystis ), or absent in Pseudocheylidae .

For nymphs and adults of Chulacarus elegans , the presence of the multiple, small genital papillae (adults with 8–10 pairs) in excess of the basic number of three pairs is remarkably unusual and not known in other terrestrial mites. These papillae are dome-like in a cross section and situated in the normal position within a progenital chamber but the exact numbers of them could not be determined due to their small size ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 D). A multiplication of the genital papillae is known in many species of water mites ( Alberti & Coons 1999 and references therein) but their multiplied genital papillae are relatively large and are external.

11. Leg I. Chulacarus elegans has the first pair of legs uniquely constructed among known species of mites. It is relatively massive, slightly curved paraxially, and increasingly twisted from proximal to distal segments such that the unipectinated claws are vertically overlapped and oriented in the same way of the pectinate setae of the genu, tibia and tarsus ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A). Its overall structure suggests a raptorial function, but we were unable to observe them alive to confirm this. However, further consideration of the gnathosoma morphology and lack of any solid particles in gut contents suggest that the new species is a predatory mite using the raptorial legs for grasping and securing their prey in soil and litter habitats. Caeculidae also have the raptorial front legs, but in a very different construction, i.e. for example, they are the members of the ventral setae that are hypertrophied and spine-like in caeculids (vs. lateral setae in Chulacarus elegans ).

12. Leg femora. Adults and juveniles of Chulacarus elegans have undivided femora of all legs ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ). This state is contrasted to the subdivision of such segments, usually occurring at post-larval stages, in most members of Anystae, including Adamystidae , Anystidae , Pomerantziidae , Pseudocheylidae , Teneriffiidae , Stigmocheylidae and most Caeculidae . Paratydeidae have divided femora I and IV while that of II and III are undivided. The undivided femora of all legs present in various superfamilies (or more major groupings) in Eleutherengona ( Lindquist 1996), some Caeculidae ( Taylor et al. 2013; Taylor 2014), the water mite families Libertiidae and Oxidae (Parasitengona) ( Bochkov & OConnor 2006), and elsewhere among acariform mites ( Grandjean 1954).

13. Solenidia. Solenidia on legs are absent from all genua in Chulacarus elegans , but present on all tibiae and on tarsi I–II, with formulas of 2-2-2-1 and 1-1-0-0, respectively. It is worth noting that one combination of these states—genua I–II and tarsi III–IV lacking solenidia—is similar to that of Heterostigmata ( Lindquist 1976; Lindquist & Krantz 2002) and this state is hypothesized to be one of the synapomorphies of the latter group. However, other members of Anystae, including Caeculidae , erythracarine Anystidae , Pseudocheylidae and Stigmocheylidae, also share this state; and it is rather common in the raphignathinan Tetranychoidea (Eleutherengona).

14. Famulus. Chulacarus elegans has a famulus on the tarsi I and II which is spiniform, erect, and long relative to the length of the solenidion, with which it forms a duplex ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A, C). Within Anystae, the presence of a famulus on the tarsi I and II is found in Adamystidae , Caeculidae , and Anystidae , they are peg-like, and sometimes in an integumental sink. It is present only on tarsus I in Pomerantziidae ; and absent in Pseudocheylidae , Teneriffiidae , Paratydeidae and Stigmocheylidae. Kethley (1990) reviewed the distribution of these setae across the prostigmatic families.

15. Empodium. In terms of presence (1) or absence (0), the empodial formula (I–IV) of Chulacarus elegans is 0-1-1-1 which is unknown in other families of Anystae, but similar to most Heterostigmata. Some erythracarine Anystidae (Tarsotomus) , and most Teneriffiidae have lost the empodium on anterior legs, having the formula of 0- 0-1-1, and those that completely lack them (0-0-0-0) are the teneriffiid genus Heteroteneriffia , Stigmocheylidae, Pomerantziidae and most Caeculidae . The normal formula (1-1-1-1) is present in most Anystidae , Adamystidae, Anystinae and most Erythracarinae , Paratydeidae , Pseudocheylidae , and some Caeculidae (Caeculus) .

Systematic placement. In the recent classifications of the suborder Prostigmata (Lindquist et al. 2009; Walter et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2011), Chulacarus elegans n. g. et n. sp. clearly belongs to the infraorder (cohort) Anystina, particularly in the hyporder Anystae, sensu Zhang et al. 2011, since it exhibits several attributes diagnostic of this group: a) the presence of separate chelicerae with a hook-like movable digit and the absence of a fixed digit; b) the presence of a palpal ‘thumb-claw’ complex; c) the presence of peritremes, d) a naso, e) prodorsal trichobothria (two pairs), and f) adanal setae. In addition, the larva of the new species retain the urstigmata; and the females possess an ovipositor, the eugenital setae, as well as the genital papillae. The presence of undivided femoral segments of legs I–IV might suggest the placement of the new taxon in Eleutherengona, but this seems unlikely since this character state is apparently homoplastic, hence has a limited value in arguing for a sister relationship ( Lindquist 1996); and, more importantly, the new taxon lacks most of the synapomorphies of Eleutherengona, viz., 1) the adnate chelicerae, 2) the movable cheliceral digits being partially retractable, 3) the absence of the genital papillae and urstigmata, 4) the closely adjacent anal and genital openings; ( Lindquist 1976; Bochkov 2009; Walter et al. 2009). Two other synapomorphies: 5) the absence of one nymph in the life-cycle (some Tuckerellidae are exceptions) and 6) the presence of an aedeagus, could not be tested for Chulacarus due to the unavailability of specimens. Chulacarus is clearly not the member of Parasitengona as it lacks the obvious unique apomorphy of this group, an heteromorphic life cycle (Walter et al. 2009).

Further consideration of the position of Chulacarus within the Anystae, however, is problematic and is further complicated by the fact that the phylogenetic relationships among families of the Prostigmata remain unresolved ( Mironov & Bochkov 2009). Of the eight anystaen families currently recognized (Walter et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2011), Chulacarus shares two apomorphies only with Teneriffiidae (discussed later). Other families can be rejected rather easily as a ‘home’ for Chulacarus since the new taxon lacks character states considered apomorphic for each of them. We list the selected characters of each family (1–7) that have different states in Chulacarus, and those considered uniquely apomorphic for the group in question are in italic font. If not specifically cited, the data are taken from various sources as listed in the previous section.

1) Adamystidae , in a broad sense, includes two subfamilies: Adamystinae and Saxidrominae—some workers recognize the latter as a separate family Saxidromidae ( Coineau et al. 2006; Fernandez et al. 2014). They have 1–3 shields partially or completely covering dorsum; auriculate naso with reticulate ornamentation; 1–2 pairs of lateral eyes; a pair of prodorsal lyrifissures present posterior to eyes; setal elements of opisthosomatic segments AN added developmentally; 2 pairs of genital papillae in adult; chelicerae weakly chelate to hook-like, base bulbous; palpi linear, with 5 free segments, palptibial claw complex absent; coxal plates I–IV contiguous, weakly radiate; leg femora divided.

2) Anystidae comprises two subfamilies: Anystinae and Erythracarinae ( Meyer & Ueckermann 1987; Otto 2000; Walter et al. 2009). But, until recently, Pepato and Klimov (2015), based on molecular analysis, showed that Anystidae is not monophyletic and elevated Erythracarinae to familial rank. Anystidae (sensu stricto) are relatively large bodied, rather short and broad; peritremes elevated; with 2 pairs of lateral eyes; post-larval hypertrichous setae present on body and legs; palptibia with 3 claws which are developmentally unique (Note 5); palptarsus well developed, inserted terminally and longer than tibial claws; sagittal apodeme present between coxae IV; coxal plates I–IV contiguous and radiate; leg femora divided; and leg tarsus with a pair of brush-like setae at bases of claws. Erythracaridae, sensu Pepato and Klimov (2015) , were cladistically analyzed by Otto (2000). According to this author, this group is unique among Prostigmata in having the flexible tarsi on all legs of the adults and nymphs ( Otto 2000), a resultant of multidivision of tarsal segments. Teneriffiidae also have a subdivision of tarsi (only on legs III–IV) but in a different fashion ( Judson 1994) from that of Erythracaridae , and is considered to occur independently.

3) Caeculidae have a large body, heavily sclerotized integuments, 8 dorsal shields in the characteristic arrangement, chelicerae each with one subterminal seta (cha), coxal plates I–IV contiguous, leg solenidia in an integumental sink, trichobothrium on leg tarsi, and raptorial front legs; the latter is very differently constructed from that of Chulacarus (Note 11).

4) Paratydeidae are elongate mites; legs I–II widely separated from legs III–IV; with distinct constrictions posterior to segment C and D (postpedal furrows); naso absent; prodorsal shield poorly defined, narrowly elongate (or crista-like); with 3 pairs of prodorsal setae of which 1 pair trichobothria (sci) always inserted on shield; 0–2 pairs of eyes; lyrifissure ia unusually located in setal row c (below insertion of setae c2); peritremes linear, located at cheliceral bases and distally elevated; chelicerae each with one subterminal seta (cha); without tibial claw complex; with 2 or 3 pairs of genital papillae; femora of legs I and IV subdivided while II–IV entire; pretarsi I–IV with smooth claws and claw like empodium.

5) Pomerantziidae are elongate mites with a series of dorsal sclerites corresponding to segments C, D, E, F, and H; legs I–II widely separated from legs III–IV; prodorsal shield bearing 3 normally developed setae (ve, sci, and sce); eyes and trichobothria absent; cupules ia, im, ip absent; peritremes short confined in between bases of chelicerae; chelicerae each with one subterminal seta (cha); adoral setae inserted without alveolus; 3 pairs of genital papillae in adult; ovipositor tubular in form and pleated; leg femora I–IV subdivided; pretarsi with claws, empodia absent.

6) Pseudocheylidae have weak to strong post-larval hypertrichy on idiosoma and legs; naso absent; with 4 pairs of prodorsal setae (bothridial setae sci, normal setae vi, ve, and sce; neotrichous setae excluded); 1 pair of lateral lens-like eyes at anterior corner of prodorsal shield; setal elements of opisthosomatic segment AD absent; genital papillae absent; peritremes linear, passing onto anterior corner of propodosoma, sometimes emergent distally; palptibia usually with 3 claw-like setae, palptarsus strongly reduced, scar-like, and lacking solenidion; leg femora I–IV subdivided; tarsi terminating as annulated stalk; pretarsi with padlike empodium; claws present or absent.

7) Stigmocheylidae are elongate mites; legs I–II widely separated from legs III–IV; and with weak constrictions posterior to segments C and D (postpedal furrows); prodorsum with poorly defined shield bearing 1 pair of bothridial setae sci and normally developed setae vi and v e (sce off shield); naso weakly developed; eyes absent; peritremes linear, located at cheliceral bases and distally elevated; with 3 pairs of genital papillae; leg femora I–IV subdivided, pretarsi I with small smooth claws and pretarsi II–IV with setulated claws; empodia absent from all legs.

As Chulacarus is most similar to the Teneriffiidae , this family is examined separately here. In addition to the characters of Anystina (Walter et al. 2009), Teneriffiidae are characterized by the following combination of character states (probable apomorphies are underlined): medium to relatively large bodied; with or without postlarval hypertrichy on coxal fields and opisthogaster; peritremes linear located at cheliceral bases and distally emergent ( Teneriffia ), or passing onto anterior corner of propodosoma (other genera) in the form of linear or numerous elongate alveolae; prodorsal shield well developed or absent (probably derived); all 4 prodorsal setae (2 bothridial setae and 2 normal setae) inserted on prodorsal shield; posterior bothridium with ‘rosette’; naso (in adults) weakly developed bearing anterior bothridial setae; naso fused to prodorsal shield; with 2 pair of lateral eyes; median eyes under naso present or absent; setal elements of opisthosomatic segment AD absent; cheliceral stylet-like process present in the position of reduced fixed digit; with 2 cheliceral setae; palptibia with 3 claw-like setae; palpal oncophysis present or absent (probably derived) between genu and tibia; palptarsus strongly reduced, disc-like; ventral lip absent; dorsal lip with denticles; adoral setae or1–2 thickened and truncated; coxal plates I–II and II–IV contiguous or proximate, and radiate; coxal plates I–II meet postero-medially or not; sagittal apodeme present; with 3 pairs genital papillae; femora I–IV divided; tarsi I–II entire, tarsi III–IV uniquely divided into 2 subsegments; trichobothrium present on tarsi III–IV and absent from tarsi I–II; pretarsi with pectinate claws; empodia absent from all legs ( Heteroteneriffia ) or present (claw-like) only on legs III–IV.

From above characters, Chulacarus is probably closely related to Teneriffiidae based on sharing at least two apomorphies:

1) The adoral setae (or1–2) being thickened and truncated —In Chulacarus and all known species of Teneriffiidae , the adoral setae are remarkably thickened and truncated (Note 2). We know no other prostigmatic families with the setae of this form;

2) The presence of the cuticular stylet on hyaline process of the chelicerae —the cheliceral stylet (Note 3) was recorded in the teneriffiid genera Neoteneriffiola and Austroteneriffia ( Judson 1994, 1995), and possibly present in all Teneriffiidae . Chulacarus shares this structure. To our knowledge no other members of Anystae exhibit this structure except Pseudocheylidae (Note 3).

In terms of classification, however, Chulacarus exhibits several conflicts of character states with all teneriffiid genera, i.e. it has a different state to most of the characters listed above for Teneriffiidae . Among these, the most important differences are 1) the presence of the ‘rosette’ of the posterior prodorsal bothridia—an unique apomorphy of teneriffiids not known in other Prostigmata—(Chulacarus has instead a few septa on the dorsal chambers of the bothridia, giving the impression of radial chambers ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C); they are very different from the teneriffiid ‘rosette’), 2) the presence of a subdivision—in a unique fashion—of tarsi III–IV (vs. entire in Chulacarus), and 3) the absence (vs. presence) of anamorphic segment AD—a familial character ( Baker & Lindquist 2002; Walter et al. 2009). Therefore, the large character gaps between Chulacarus and Teneriffiidae (and other anystaen taxa) justifies the proposal of a monotypic new family, Chulacaridae n. fam. Further superfamilial affiliation of Chulacaridae is considered uncertain pending further research; it is placed tentatively within the superfamily Anystoidea.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Chulacarus elegans

| Fuangarworn, Marut, Lekprayoon, Chariya & Butcher, Buntika Areekul 2016 |

Adamystidae (

| Coineau & Naudo 1986 |