Endecous (Endecous) zaum, Carvalho & Junta & Castro-Souza & Ferreira, 2023

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5263.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3386FD59-2075-4F6A-8B21-B36C7F463EA9 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7797753 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B3578783-FFA5-E841-FF44-F90CFB2B89F8 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Endecous (Endecous) zaum |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Endecous (Endecous) zaum n. sp.

( Figures 67 – 71 View FIGURES 67–71 , 72 – 80 View FIGURES 72–80 , 81 – 82 View FIGURES 81–82 , 83 – 86 View FIGURES 83–86 , 87 – 92 View FIGURES 87–92 , 93 – 97 View FIGURES 93–97 ; Table 3)

Material examined. Holotype, ♁, code ISL 104855, Brazil, Bahia, municipality of Coribe, Serra Verde cave (44°19′26.85″W, 13°43′28.04″S), 20.ix.2021, R. L. Ferreira; condition: right tegmen, left legs and phallic complex were detached/dissected and stored alongside the holotype GoogleMaps . Paratypes, 9 ♁♁, ISLA 104852, 104853, 104854, municipality of Coribe , Serra Verde cave (44°19′26.85″W, 13°43′28.04″S), 20.ix.2021, R. L. Ferreira GoogleMaps ; ISLA 104856, 104857, municipality of Coribe , Gruna do Enfurnado cave (44°12′7.99″W, 13°38′45.69″S), 25.viii.2022, R. L. Ferreira GoogleMaps ; ISLA 104858, 104859, 104860, 104861, municipality of Coribe , Gruna do Zeferini cave (44°14′4.52′′W, 13°46′15.55″S), 24.viii.2022, R. L. Ferreira GoogleMaps .

Etymology. The epithet “zaum” is a Russian term composed by the prefix ЗА (beyond) and ум (mind, knowledge). Hence, it literally means “beyond knowledge”. This term should be treated as a noun in apposition.

Diagnosis. Combination of the following characteristics: pseudepiphallic dorsal branches (Ps.db) elongated, dorsally projected and pointing to the center of the phallic complex, distal portion turning inwards abruptly in relation to the proximal portion; pseudepiphallic ventral branches (A) elongated, apex dilated and rounded; pseudepiphallic inner bars (Ps.ib) flat and inclined inwards; pseudepiphallic rami (R) developed, forming a membranous shield that covers the most proximal portion of the ectophallic apodeme; ectophallic arc (Ect.arc) rounded at the posterior and anterior middle portions; ectophallic lateral bars (Ect.lb) elongated, sinuous and rounded at the apex; endophallic sclerite anterior portion (End.sc.a) with a crest on the opposite side of its central groove.

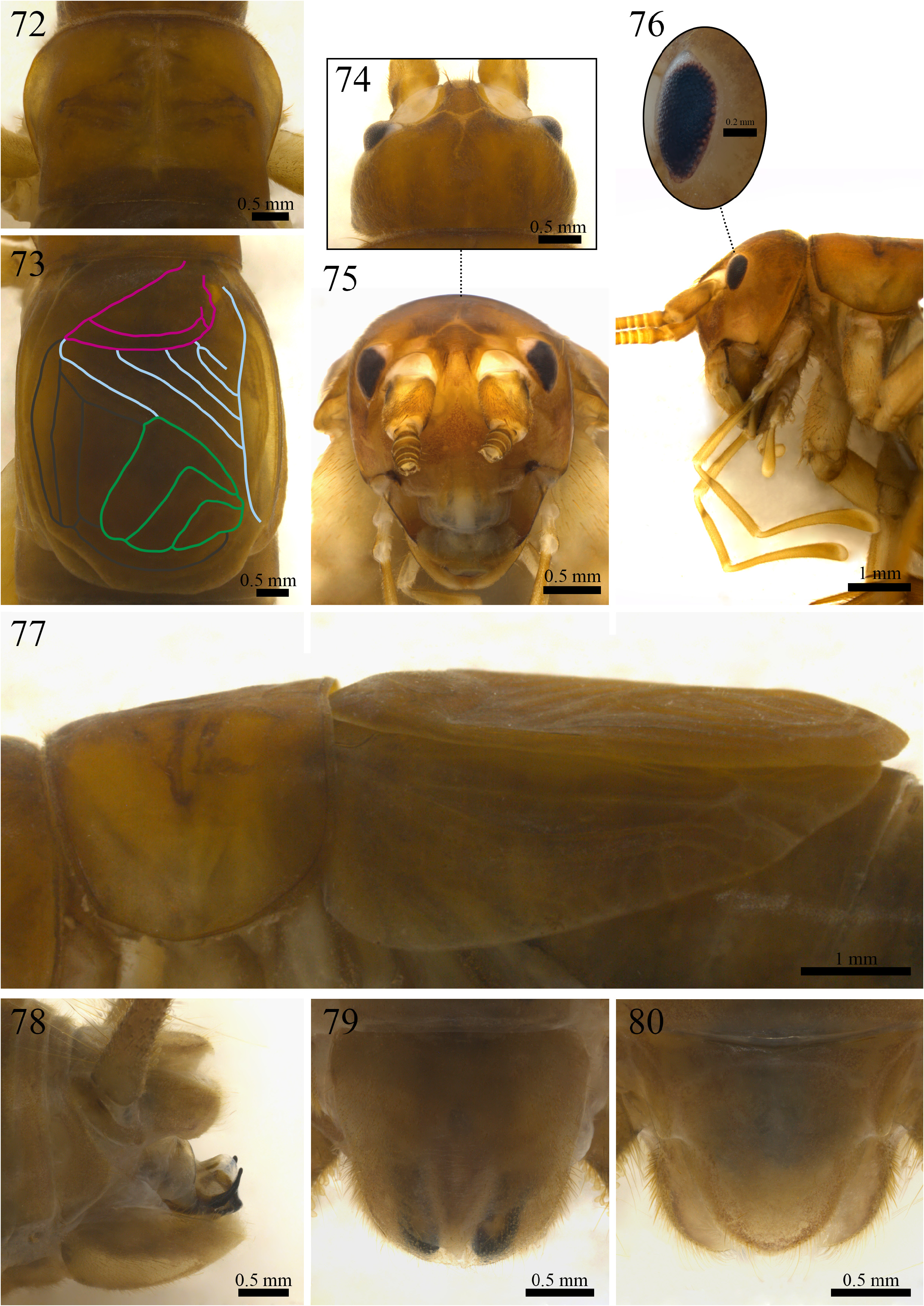

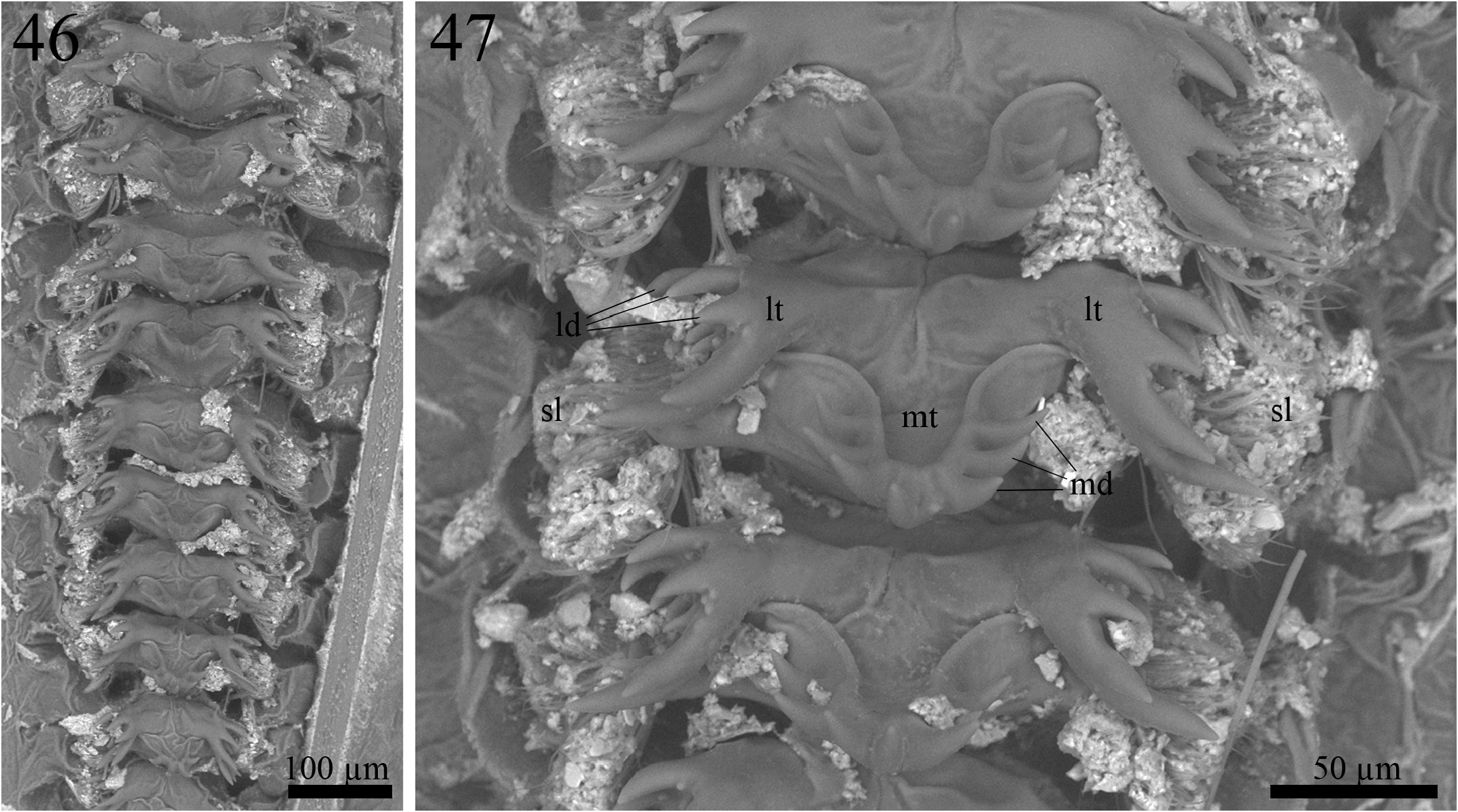

Morphology (paratype ISLA 104854, Figs. 72–80 View FIGURES 72–80 ). Body color: dorsal head yellowish brown with irregular brown patches; pronotum yellowish brown; abdomen brown dorsally and whitish ventrally (Figs. 72,74–80); entire legs yellowish brown, whitish at their proximal portion ( Figs. 83–86 View FIGURES 83–86 ); cerci brown at the base and yellowish brown towards the apex ( Fig. 78 View FIGURES 72–80 ). Head: slightly pubescent, elongated in frontal view; front brown; gena yellowish brown; fastigium with long bristles, extending the vertex in an inclined plane pointing downwards; clypeus and labrum whitish; mandibles yellowish brown and more sclerotized at the apex and margins; maxiles whitish and more sclerotized at the apex ( Fig. 75 View FIGURES 72–80 ); all maxillary palpomeres pubescent, the first two whitish, short and same-sized, the other three palpomeres yellowish brown and longer, the palpomere V (1.81 mm) is claviform and whitish at the apex ( Fig. 76 View FIGURES 72–80 ); all labial palpomeres light yellowish brown, pubescent, increasing in size, the third one dilated from base to apex, which is whitish ( Fig. 76 View FIGURES 72–80 ); scape, pedicel and flagellomeres yellowish brown, distal portion whitish ( Fig. 76 View FIGURES 72–80 ); compound eyes reduced, ommatidia black; ocelli absent ( Fig. 46 View FIGURES 46–47 ). Thorax: pronotum lateroanterior and lateroposterior regions with long bristles; dorsal disk broader than long (2.55 and 3.51 mm in length and width, respectively), lateral lobes rounded and leaning towards the anterior portion of the body, anterior and posterior margins arched and sub-straight ( Figs. 72 and 77 View FIGURES 72–80 ). Legs: femur, tibia and tarsus pubescent ( Figs. 83–86 View FIGURES 83–86 ). Leg I ( Figs. 85 and 86 View FIGURES 83–86 ): tibia slightly longer than the femur, with an oval tympanum on its inner side and two same-sized ventral apical spurs, first tarsomere ventrally serrated and longer than the second and third tarsomeres together. Leg II ( Figs. 85 and 86 View FIGURES 83–86 ): tibia slightly longer than the femur, with two same-sized ventral apical spurs, first tarsomere ventrally serrated and longer than the second and third tarsomeres together. Leg III ( Figs. 83 and 84 View FIGURES 83–86 ): femur developed; tibia longer than the femur (12.49 and 10.99 mm respectively); tibia armed with four subapical spurs on the outer side, the distal being the shortest, and three on the inner side, the proximal being the shortest, three apical spurs on the outer side ( Fig. 84 View FIGURES 83–86 ; a, b, c), spur “a” being the longest and “c” the shortest, and four on the inner side ( Fig. 83 View FIGURES 83–86 ; d, e, f, g), spurs “e” and “f” longer than the “d” and “g”; first tarsomere longer than the second and third tarsomeres together, with two apical spurs, the inner one being the longest. Right tegmen: slightly sclerotized; covering the first three urotergites (5.22 and 4.17 mm in length and width, respectively); harp with five cells and four well-marked crossveins, the two most proximal ones share the same origin point, a fifth crossvein is visible, but short and does not reach the opposite margin of the harp; mirror with two distinct crossveins and three cells; basal field with a single and short secondary vein connecting Cu2 to 1A; lateral field with two longitudinal veins and several irregular and weakly marked veins ( Fig. 73 View FIGURES 72–80 ); stridulatory file with 95 teeth. Abdomen: cerci pubescent, with globose setae at the base, mainly on the inner side, and long bristles throughout all their extension; sub-genital plate whitish brown, U-shaped, proximal margin broader than the distal margin, which is rounded ( Fig. 79 View FIGURES 72–80 ); supra-anal plate yellowish-brown, subtriangular, distal margin rounded lateral projections short and slightly curved outwards ( Fig. 80 View FIGURES 72–80 ); paraprocts as long as the supra-anal plate, projecting themselves laterally and, therefore, visible in dorsal view ( Figs. 78 and 80 View FIGURES 72–80 ).

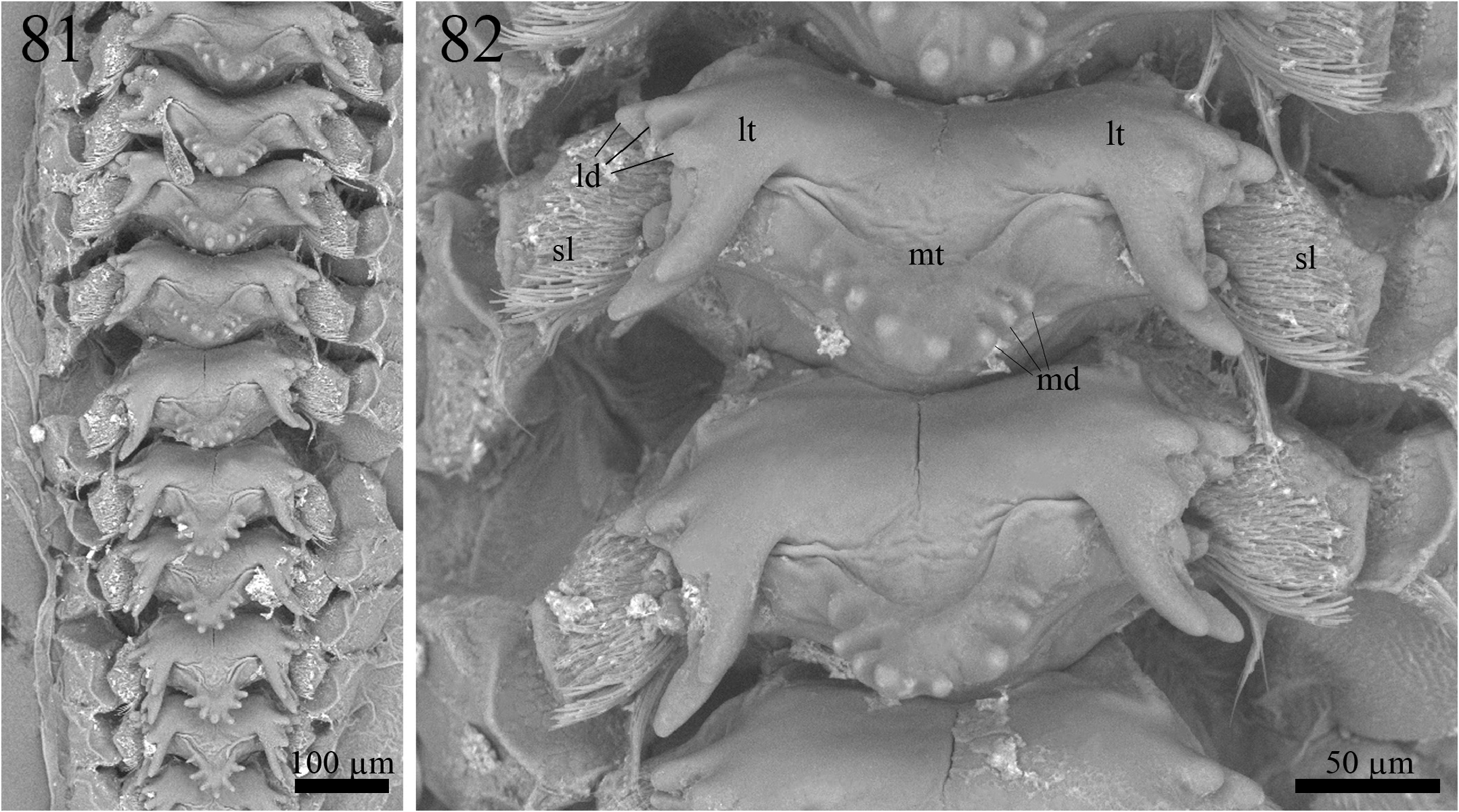

Proventriculus (paratype ISLA 104852, Figs. 81–82 View FIGURES 81–82 ). Proventriculus internally organized in six rows of 11 or 12 overlaid sclerotized appendices (sa); sclerotized lobes (sl) bearing a cluster of bristles are visible on each side of the sclerotized appendices; sclerotized appendices formed by a median tooth (mt), with at least five, but up to nine median denticles (md), and two lateral teeth (lt), with several lateral denticles (ld); median denticles short and rounded at the tip; lateral denticles also short and rounded at the tip; the most posterior median tooth bears two or three short median denticles; the most posterior sclerotized appendix does not have a median tooth.

Male phallic sclerites (holotype ISLA 104855, Figs. 67–71 View FIGURES 67–71 ). Phallic complex broadened at the proximal and central portions, with an almost trapezoidal contour in dorsal and ventral views ( Figs. 67 and 68 View FIGURES 67–71 ). Pseudepiphallus: arms short and inclined inwards in dorsal view ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ps.arm); dorsal branches long, projecting dorsally towards the center of the phallic complex, with the distal half virtually perpendicular to the proximal half in dorsal view, apexes slightly dilated, rounded at the tip and almost touching each other in frontal view ( Fig. 70 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ps.db); “A” sclerite welldeveloped, elongated and dilated at the apex, with a rounded tip ( Figs. 69–71 View FIGURES 67–71 , A); paramere 1 and 2 fused in a single circular and concave structure, bean-shaped in frontal view, distal region highly sclerotized, ventral region exceeding the length of the dorsal branches in both dorsal and ventral views, dorsal portion sclerotized, forming a scythe-like edge that reaches the ventral side of the posterior portion of the ectophallic median projections ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ps.p); inner bars flat and slightly inclined downwards in dorsal view ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ps.ib); rami developed, forming a membranous shield that covers only the proximal portion of the ectophallic apodeme in lateral view ( Fig. 71 View FIGURES 67–71 , R). Ectophallic invagination: arc well-developed, wide, dome-shaped at both posterior and anterior central parts in ventral view ( Fig. 68 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ect.arc); apodeme developed and slightly curved inwards in dorsal view ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ect.ap); lateral bars welldeveloped, sinuous, slightly inclined inwards, longer than the ectophallic median projections, with a rounded apex and almost touching the parameres in ventral view ( Fig. 68 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ect.lb); median projections slender, elongated, reaching the parameres, slender and slightly curved outwards in dorsal view ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 67–71 , Ect.mp). Endophallus: anterior portion well-developed and sclerotized, with a central groove and a dorsal crest, opposite to the groove in lateral view ( Fig. 71 View FIGURES 67–71 , End.sc.a); duct short, membranous throughout all its extension, which subceeds the length of the ectophallic apodeme in ventral view ( Fig. 68 View FIGURES 67–71 , End.sc.d); posterior portion membranous, trapeze-shaped, exceeding the length of the ectophallic median projections considerably and almost reaching the pseudepiphallic dorsal branches at their apexes in dorsal view ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 67–71 , End.sc.p).

Variations in phallic sclerites (paratypes, n = 6, ISLA 104852, 104853, 104854, 104856, 104860, 104861). Phallic complexes vary slightly in degree of sclerotization; pseudepiphallic arms (Ps.arm) vary subtly in degree of inclination towards the center of the sclerite; pseudepiphallic dorsal branches (Ps.db) always bent abruptly towards the interior of the sclerite, but may not be perpendicular to the pseudepiphallic arms; pseudepiphallic inner bars (Ps. ib) may be more or less inclined to the anterior portion of the phallic complex; anterior margin of the ectophallic arch (Ect.arc) may be more or less curved; ectophallic apodeme (Ect.ap) may be more or less inclined towards the interior of the sclerite; endophallic sclerite posterior portion (End.sc.p) shape varies slightly, yet retains the trapezoidal outline.

Variations in male right tegmen ( Figs. 87 – 92 View FIGURES 87–92 ). Stridulatory file with 87.10 ± 5.17 teeth (n° = 10, holotype and paratypes). Harp outline conserved; four or five diagonal crossveins and five or six cells; a short and irregular crossvein may be present ( Figs. 87, 89 and 92 View FIGURES 87–92 ). Mirror outline always triangular, with a trapezoidal apex; two complete, V-shaped crossveins ( Figs. 87, 89 and 92 View FIGURES 87–92 ), two incomplete veins ( Fig. 88 View FIGURES 87–92 ) one complete vein ( Fig. 91 View FIGURES 87–92 ) or one incomplete vein ( Fig. 90 View FIGURES 87–92 ); a third short, diagonal vein may be present ( Fig. 88 View FIGURES 87–92 ). Basal field outline conserved; 1A may branch out into several irregular and poorly marked veins ( Fig. 88 View FIGURES 87–92 ). Lateral field with two parallel longitudinal veins, which may be curved outwards.

Ecological remarks. Specimens of Endecous zaum n. sp. were observed in the Serra Verde, Gruna do Enfurnado and Gruna do Zeferini caves. However, many other caves exist in the area (most of them not biologically studied), so it is likely that other populations of E. zaum n. sp. may be found in the future.

Serra Verde cave (the type locality) has at least 1,730 meters of horizontal projection, but it is still under exploration, so it might be longer than currently known. Even though the cave has a relatively wide entrance ( Fig. 94 View FIGURES 93–97 ), there is a constriction in the main conduit around 20 meters from the entrance, which prevents the locals from accessing the cave interior. The conduit that follows this constriction is relatively dry. Nevertheless, there are signs that the runoff water penetrates the cave in rainy periods. Our team visited the cave during the dry season, hence, the substrates were predominantly dry near the entrance. Nonetheless, it is important to mention that galleries became progressively wetter as depth increased, the conduits at the final portion of the cave being drenched in water ( Fig. 95 View FIGURES 93–97 ). Specimens of E. zaum n. sp. were observed in the humid galleries, far from the entrance, being more frequent in deeper regions of the cave. Individuals were most often seen on the cave floor ( Fig. 96 View FIGURES 93–97 ). The predominant organic resources were bat guano (especially produced by vampire bats— Desmodus rotundus ) and plant debris brought by the water. In previous expeditions, speleologists discovered that the inner conduits partially flood during the rainy season, thus indicating that the water table varies greatly throughout the year. For that reason, it is fair to assume that these crickets probably migrate during rainy seasons to regions closer to the entrance that are not flooded.

As aforementioned, the constriction on the conduit close to the entrance of the cave hinders the access of locals to its interior, which in turn guarantees the preservation of the cave’s inner environment. The external landscape, however, is severely altered, especially close to the limestone outcrops, where only a few remnants of the original vegetation can be verified ( Fig. 93 View FIGURES 93–97 ). Pastures replaced most of the native forests and cattle were observed in the cave surroundings ( Fig. 97 View FIGURES 93–97 ), compacting the exposed soil, which is highly vulnerable to erosive processes. Additionally, since the cave entrance is located at the bottom of a valley, the external topography ends up contributing to the input of sediments to the cave during rainy periods. The soil denudation in the external landscape can, therefore, intensify erosive processes, increasing the sediment input to the cave, and, consequently, silting up important microhabitats. Accordingly, it is highly recommendable to protect the cave surroundings, especially through the reforestation of the immediate external landscape, to preserve the cave and the species that it harbors.

The other two caves where specimens were found (Gruna do Enfurnado and Gruna do Zeferini caves) are quite distinct from each other and from Serra Verde cave, thus indicating the species is quite versatile in occupying different caves. Whilst Zeferini cave is mostly dry (there is only one pond on the cave), the Enfurnado cave is trespassed by a stream. The cave´s sizes are also very distinct: Zeferini cave has around 300 meters, while Enfurnado cave has more than 7.5 km in extension. As observed for the Serra Verde cave, the external surroundings of both the Zeferini and Enfurnado caves are also altered by human activities, especially farming (crops and pastures).

| R |

Departamento de Geologia, Universidad de Chile |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SuperFamily |

Grylloidea |

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Luzarinae |

|

Genus |

|

|

SubGenus |

Endecous |