Diopsidae Billberg, 1820

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4735.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:BD52DF91-3A7E-46FB-8975-38A67BFBBD61 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3679582 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BD15296C-6A73-FF95-FF1A-F842DD10A06A |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Diopsidae Billberg, 1820 |

| status |

|

Diopsidae Billberg, 1820 View in CoL View at ENA

( Figs 143–190 View FIGURES 143–152 View FIGURES 153–159 View FIGURES 160–168 View FIGURES 169–176 View FIGURES 177–183 View FIGURES 184–190 , 405–410 View FIGURES 403–410 )

Type genus: Diopsis Linnaeus 1775: 5 View in CoL , by Billberg, 1820: 115 [as “Diopsides”]. Type species of genus: Diopsis ichneumonea Linnaeus, 1775: 5 View in CoL , by monotypy.

At least 170 species in 13 genera are known (Meier & Hilger, 2000; Meier & Baker, 2002). Most are restricted to the Afrotropical Region, but many also occur in the Oriental Region. No species are found in the Neotropics, and very few occur in the Palaearctic and Australian Regions (Papp, Földvári & Paulovics, 1997; Feijen, 1989). The two New World species, found in North America east of the Rockies, are treated in Feijen (1989), who also provides a synopsis of the world genera. Revisions of genera are ongoing, with several new species recently described (eg. Feijen & Feijen, 2012, 2013).

Centrioncinae consists of the single genus Centrioncus , containing 22 described species from montane afrotropical forests. Due to their characteristic distribution, Feijen adopted the common name of “Afromontane forest flies”. Species include Speiser’s 1910 genotype ( C. prodiopsis Speiser ), one species more recently described by DeMeyer (2004), and 20 species described by Feijen (1983) in his thorough revision of the “Centrionicidae”. Feijen (1983) also included in this family his new genus Teloglabrus , which McAlpine (1997b) recommended treating as a junior synonym of Centrioncus .

While the subfamily is largely defined on genitalic features ( Feijen, 1983) impractical for diagnosis, it is readily characterized by having many of the synapomorphies of the Diopsidae with the conspicuous absence of eye stalks ( Figs 130–133 View FIGURES 124–133 ): a scutellum with long apical spines ( Fig. 130 View FIGURES 124–133 , arrow), a bulbous katatergite (but without a spine), tarsi with dark “sawlines” lengthwise along the tarsomeres ( Fig. 131 View FIGURES 124–133 ), absence of bm-m ( Fig. 405 View FIGURES 403–410 ), a porrect antenna, raptorial fore legs, and only one outer vertical and one fronto-orbital seta.

The readily identifiable Diopsinae includes Prospyracephala and the tribes Diopsini and Sphyracephalini. It was defined by Hennig (1965) as having eye stalks with the antennae approximate to the separated eye margins ( Figs 143–152 View FIGURES 143–152 ), one spine on a bulbous katatergite, a glabrous arista, an elongate cell cu a (except Prosphyracephala ) ( Figs 407–410 View FIGURES 403–410 ), veins M 4 and CuA+CuP not extending to the wing margin, absence of the supra-alar and notopleural setae, loss of the tubercles on the hind femur, and usually an additonal subapical seta on the mid tibia. Prospyracephala is known from P. breviata (Meunier) from Baltic amber; P. succini (Loew) , recovered from early Oligocene Baltic, Miocene Saxon and Eocene Rovno amber ( Feijen, 1989; Schumann, 1994; Perkovsky et al., 2015); P. kerneggeri Kotrba , from Baltic amber (Kotrba, 2009); the tentatively placed P. rubiensis Lewis , from shale deposits in Montana (late Oligocene); and one unnamed specimen from oil-shale sediments in France (lower Oligocene) ( Lutz, 1985). The only other known fossil Diopsidae are several specimens of Diopsis listed in Handlirch (1906 –1908), and while Hennig (1965) believed these to also likely represent Prospyracephala, this is yet to be verified.

The tribe Sphyracephalini consists largely of Sphyracephala species ( Figs 143–147 View FIGURES 143–152 , 160–168 View FIGURES 160–168 ), which unlike most other Diopsinae, has relatively short eye stalks, and extends from the Old World tropics and subtropics into the north temperate Regions, including two species in North America ( Feijen, 1989). Clarification of tribal boundaries was provided by Kotrba & Balke (2006), who found strong support for inclusion of the malagasy Cladodiopsis Séguy in Sphyracephalini using morphologial and molecular data.

The Diopsini is a diverse tribe encompassing most diopsid genera. It is defined by reduced segmentation of the arista, absence of CuA+CuP past cell cu a ( Figs 408–410 View FIGURES 403–410 ), fusion of tergites 3 and sometimes 4 to syntergite 1+2, a reduced male S8 ( Fig. 170 View FIGURES 169–176 ), reduced scutellar setae, reduction of the alula and anal lobe, and often much longer eye stalks ( Figs 148–152 View FIGURES 143–152 ) (Meier & Hilger, 2000; Kotrba, 2004). Ten genera were recognized in Feijen (1989), but Meier & Baker (2002) synonymized (or reinstated the previous synonymies of) Cyrtodiopsis with Teleopsis , and Trichodiopsis and Chaetodiopsis with Diasemopsis . Additional studies will very likely produce additional generic redefinitions.

Treatments of Diopsidae in the literature include regional catalogues by Sabrosky (1965a), Feijen (1989) [Nearctic], Hennig (1941c) [Palaearctic], Steyskal (1977f) [Oriental], Evenhuis (1989e) [Australian] and Cogan & Shillito (1980) [Afrotropics]. A World catalogue was developed by Steyskal (1972). Other major taxonomic works include Shillito (1940), who revised the family at the genus level, Shillito (1971), who reviewed the diopsid genera and attempted a reconstruction of phylogeny, and Feijen (1984, 1989), who listed the diopsoid genera and reviewed the family (sensu Feijen (1983)). Feijen (1989) also presents the most recent genus key, as well as an extensive synopsis of morphology and a synopsis of the group’s treatment in the literature. Shillito (1960, 1976) assembled a bibliography of major works on the family. A more recent summary of studies in taxonomy and organismal biology is provided in Meier & Hilger (2000) and Meier & Baker (2002), who also developed diopsid phylogenetics consid- erably via numerical analyses. Phylogenetics of the family was additionally treated in Baker et al. (2001), Baker & Wilkinson (2001), Kotrba (2004) and Kotrba & Balke (2006). Kotrba (1995) investigated the female terminalia of select Diopsini and provided a summary of similar works on the subject.

Biology. Species are often found in rather wet, humid and shady areas, often on low foliage, especially near streams, with the adults feeding on liquefied plant and animal material, and larvae being mostly saprophagous or facultatively phytophagous, associating with plants with existing primary damage ( Oosterbroek, 1998, Meier & Hilger, 2000; Marshall, 2012). A few are obligate phytophages, including those species of agricultural relevance (Meier & Hilger, 2000), and while several African grass-feeding species are regularly found stem-boring on crops such as sugar cane and maize, only the rice-feeding Diopsis longicornis Macquart is known to be pestiferous ( Feijen, 1989).

A summary of feeding strategies is presented in Ferrar (1987), a discussion of agricultural impact and life history is provided in Feijen (1989), and literature pertaining to host use and life history are summarized in Shillito (1960, 1974). Adults are weak fliers and sometimes known to be gregarious ( Feijen, 1989).

The unusual eye stalks of this family has made it an attractive subject for ethologists and evolutionary biologists. A thorough summary of varied aspects of diopsid behaviour was provided in Feijen (1989), including descriptions of agonistic, precopulatory and copulatory behaviour, as well as the defence of territories through display and sometimes physical combat. Much attention has been given to the origin of increased eye span, male agonistic behaviour, female sexual selection and inherited fitness.As eye stalk length can be correlated to fitness, they provide exaggerated intraspecific signals linked to success in female sexual selection and better assessment of body size between rival males; this signalling is useful in resolving male contests because both time and the physical investment required for battle are costly ( Panhuis & Wilkinson, 1999), although the degree to which this is true remains uncertain ( Brandt & Swallow, 2009). While eyespan is usually directly correlated to body length, dimorphism—wherein male eyespan increases geometrically with body length (Burkhardt et al., 1994)—has evolved at least four times in the family (Baker & Wilkinson, 2001).

Immature stages. The egg, larval instars and puparia of Sphyracephalini and Diopsini are described and illustrated in Feijen (1989). Descriptions of immature stages are also documented in Descamps (1957), and eggs are thoroughly documented for most genera in Meier & Hilger (2000).

Adult Diagnosis. Stout-bodied and often heavily sclerotized flies, with representatives of the Diopsinae characterized by eye stalks in both sexes, which unlike other stalk-eyed flies (some Tephritidae , Drosophilidae , etc.), have the antenna removed to the end of the stalks near the eye margin ( Figs 145, 151 View FIGURES 143–152 ). Body length 3.0–12.0mm; eye span 1.5–17.0mm. Antenna porrect; pedicel without dorsal seam; arista inserted dorsoapically (not dorsobasally) and with vestiture very short to absent. Vibrissa, postocellar and inner vertical setae absent; ocellar seta minute and setula-like if present; one fronto-orbital. Face well-sclerotized; Diopsinae with face almost to entirely absent, compressed into facial sulcus ( Fig. 145 View FIGURES 143–152 ). Apical scutellar seta on long, thin process (arrow, Fig. 130 View FIGURES 124–133 ), lateral seta absent; katatergite with bulging “callus” produced apically into long spine in Diopsinae. Precoxal bridge present to absent; postmetacoxal bridge present. Fore coxa lengthened and fore femur enlarged with ventral rows of spines ( Figs 131 View FIGURES 124–133 , 144 View FIGURES 143–152 ); hind femur slender with posteroventral row of spines; tarsal “sawlines” present on mid and hind legs (see Fig. 131 View FIGURES 124–133 ; McAlpine (1997b: fig. 40)). Vein bm-m absent; costa unbroken; subcosta complete ( Figs 405–410 View FIGURES 403–410 ).

Adult Definition. Colour black to brown or reddish, sometimes with yellow and/or white patches ( Figs 130– 152 View FIGURES 124–133 View FIGURES 134–139 View FIGURES 140–142 View FIGURES 143–152 ). Body length 3.0–12.0mm; eye span 1.5–17.0mm (greater in males if species sexually dimorphic).

Chaetotaxy: 1 outer vertical; 0–1 fronto-orbital (sometimes reduced when present) [=inner vertical in Diopsinae of Feijen (1983, 1989)]; Diopsina draconigena Feijen apparently with small orbital and 4 pairs of fronto-orbitals [not examined, possibly enlarged setulae]; minute setula-like ocellar sometimes present; 0 postocellar; pedicel in Diopsinae with apical ring of setulae (sometimes reduced) including one larger dorsal and ventral setula. 0 anterior notopleural, 0–1 posterior notopleural; 0–1 posterior supra-alar on shallow to pronounced supra-alar carina (slightly inset from level of notopleural in Centrioncinae, more medially displaced in Diopsinae); 1 posterior intra-alar; 0–1 postsutural dorsocentral; 0–1 lateral scutellar, 0–1 apical scutellar; 0 setae on pleuron. Body usually covered with minute setulae, sometimes providing a grey or silvery sheen; Diopsinae often also with much longer setulae (sparse to dense) across body, appearing as thin and often paler setae, and/or with patches of body surface partially to entirely glabrous, or with glabrous pattern; Diopsis and Eurydiopsis sometimes with thoracic setae absent excluding apical scutellar and intra-alar. Mid tibia with relatively small ventral subapical seta that is stronger and duplicated in Diopsinae.

Head. Antenna porrect, relatively short with first flagellomere subovate; pedicel without dorsal seam; arista inserted dorsoapically to dorsomedially (not dorsobasally); arista pubescent (Centrioncinae) to glabrous (Diopsinae). Fronto-orbital sometimes arising from tubercle. Face well-sclerotized; Diopsinae with face almost entirely absent, compressed into facial sulcus (sometimes obliterated) resulting from meeting of genal/parafacial plates along midline ( Fig. 145 View FIGURES 143–152 ) (small portion of face sometimes evident dorsally where sulcus meets ptilinal suture); Diopsini sometimes with genovertical plate produced into anteroventral “peristomal teeth”. Buccal cavity relatively broad. Ptilinum well-developed. Eye with anteromedial ommatidia enlarged. Diopsinae with eyes and antennae removed to ends of stalks that may exceed body length, with sexual dimorphism evident in some species. Ocelli slightly raised, appearing closer to centre of frons in species with eye stalks where frons is broadly rounded. Clypeus broadly rounded and sometimes projecting; palpus slender and subcylindrical to slightly compressed laterally; labium with sides rounded, with broad distal emargination and with one pair of pronounced setae. Back of head with small process above foramen magnum that in Diopsinae is slightly elongate and dorsoapically produced, articulating with bulbous dorsal concavity on pronotal collar ( Fig. 147 View FIGURES 143–152 ).

Thorax. Stout, well sclerotized and convex. Proepisternum shifted dorsally, displacing postpronotum posteriorly. Scutum narrowing anteriorly and sharply narrowing posteriorly, particularly in Diopsinae, leaving margin above wing base pronounced; vertical posterolateral section of scutum beside scutellum sometimes enlarged, displacing disc of scutum anteriorly. Anteromedial section of pronotum produced as pronotal collar; forming slight dorsomedial extension in Centrioncinae ( Figs 130–131 View FIGURES 124–133 ); larger in Diopsinae, incorporating some or all of proepisternum, sometimes very pronounced and elongate, with proepisterna enlarged and meeting, or nearly meeting dorsomedially ( Figs 149–150 View FIGURES 143–152 ). Precoxal bridge present or absent; some Diopsinae with membrane surrounding prosternum slightly sclerotized or forming semi-discrete plate; prosternum setose; postmetacoxal bridge present. Transverse suture (visible on lateral 1/3 of scutum) and margin of postpronotum clearly delimited by glabrous groove. Scutum with thin carina over wing base (bearing seta in Centrioncinae) that is produced into spine medially in some Diopsini. Anepisternum with vertical posterodorsal and ventromedial grooves that sometimes meet medially; Diopsinae with katepisternum and meron fused with suture sometimes reduced to almost entirely absent; coxopleural streak absent. Greater ampulla broad, shallow. Katatergite with bulging “callus” sometimes produced as a spine. Metasternum not extending between hind coxae and not attached to postmetacoxal bridge, which is straight along ventral margin. Metathorax with cylindrical extension meeting abdomen. Scutellum broadly attached to scutum with reinforced dorsal and ventral ridges extending laterally along scutal margin; apical scutellar setae on spines that are narrow and subcylindrical (Centrioncinae, Sphyracephalini and some Diopsini) to elongate conical (some Diopsini, with setae sometimes absent).

Wing. ( Figs 405–410 View FIGURES 403–410 ) Wing relatively narrow, with anal lobe and alula sometimes reduced or absent (Diopsinae), wing rarely reduced; clear to variably infuscated or otherwise patterned with spots or bands. Vein bm-m ab- sent; costa unbroken, extending to M 1; subcosta complete. Veins R 4+5 and M 1 subparallel to slightly converging. Vein CuA+CuP reaching wing margin (Centrioncinae), short (Sphyracephalini) or absent (Diopsini). Cell cu a relatively narrow in Diopsinae, becoming elongate in Diopsini; vein CuA long and straight in Centrioncinae, narrow and rounded in Diopsinae. Calypter hairs of moderate length, not long. Wings sometimes relatively weakly developed; Diopsina draconigena brachypterous.

Legs. Fore coxa elongate; fore femur swollen ( Fig. 131 View FIGURES 124–133 ) (narrower in some Diopsini ( Fig. 150 View FIGURES 143–152 ), particularly Diopsis ) with two distoventral rows of spinous setae (rows long to very short); Diopsinae with spines on fore femur sometimes accompanied by 2 (less commonly 1) pronounced rows of longer spinous setae; hind femur sometimes also swollen ( Eosiopsis Feijen ). Hind femur with short row of much smaller posterodistal tubercles in Centrioncinae. Femoral glands absent. Fore tibia with double ventral scalloped ridge that is often black and heavily sclerotized, and sometimes slightly curved to match contour of enlarged femur; Centrioncinae with fore tibial brush discrete, pale, visibly contasting surrounding dark setae. Fore tarsi usually shorter than fore tibia. Mid and hind tarsi with “sawlines” ( Fig. 131 View FIGURES 124–133 ) that are sometimes reduced in Sphyracephala .

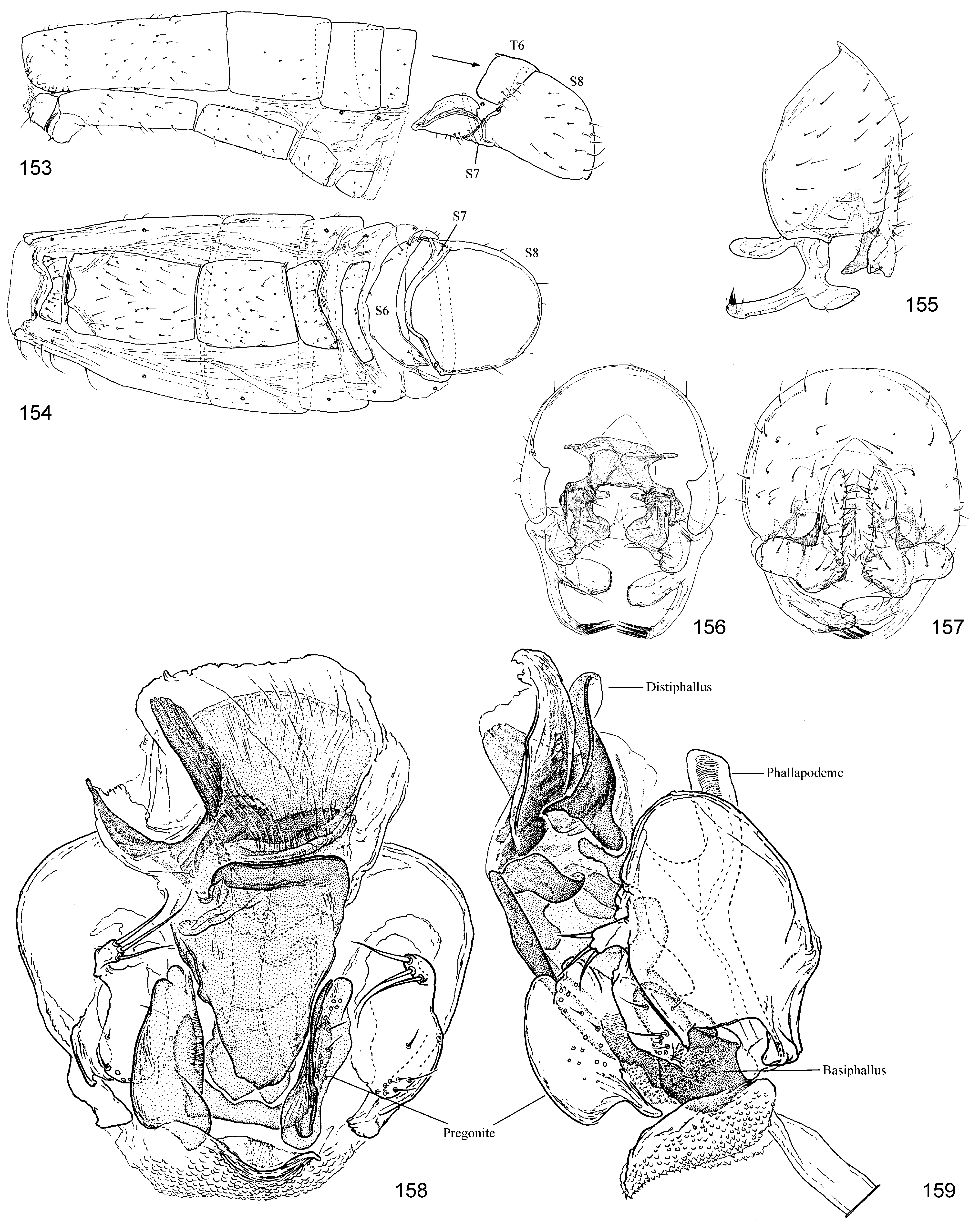

Abdomen. Abdomen narrowed basally, sometimes distinctly clavate or petiolate. Spiracles 1–7 usually in membrane below tergite, sometimes with spiracle 1 enclosed in tergite and sometimes female spiracle 7 enclosed in tergite ( Fig. 178 View FIGURES 177–183 ); male with last pair of spiracles enclosed in pregenital sclerites, or just anterior to them ( Figs 153–154 View FIGURES 153–159 ). Syntergite normally consisting of tergites 1 and 2, but sometimes also 3(4), with sutures variably evident. Sternite 1 well-developed, wider than long ( Fig. 154 View FIGURES 153–159 ); posteromedial margin of S1 with dark, thin transverse sclerotized band, often separated from sternite as separate, floating sclerite. Sternites 2 and 3 largest.

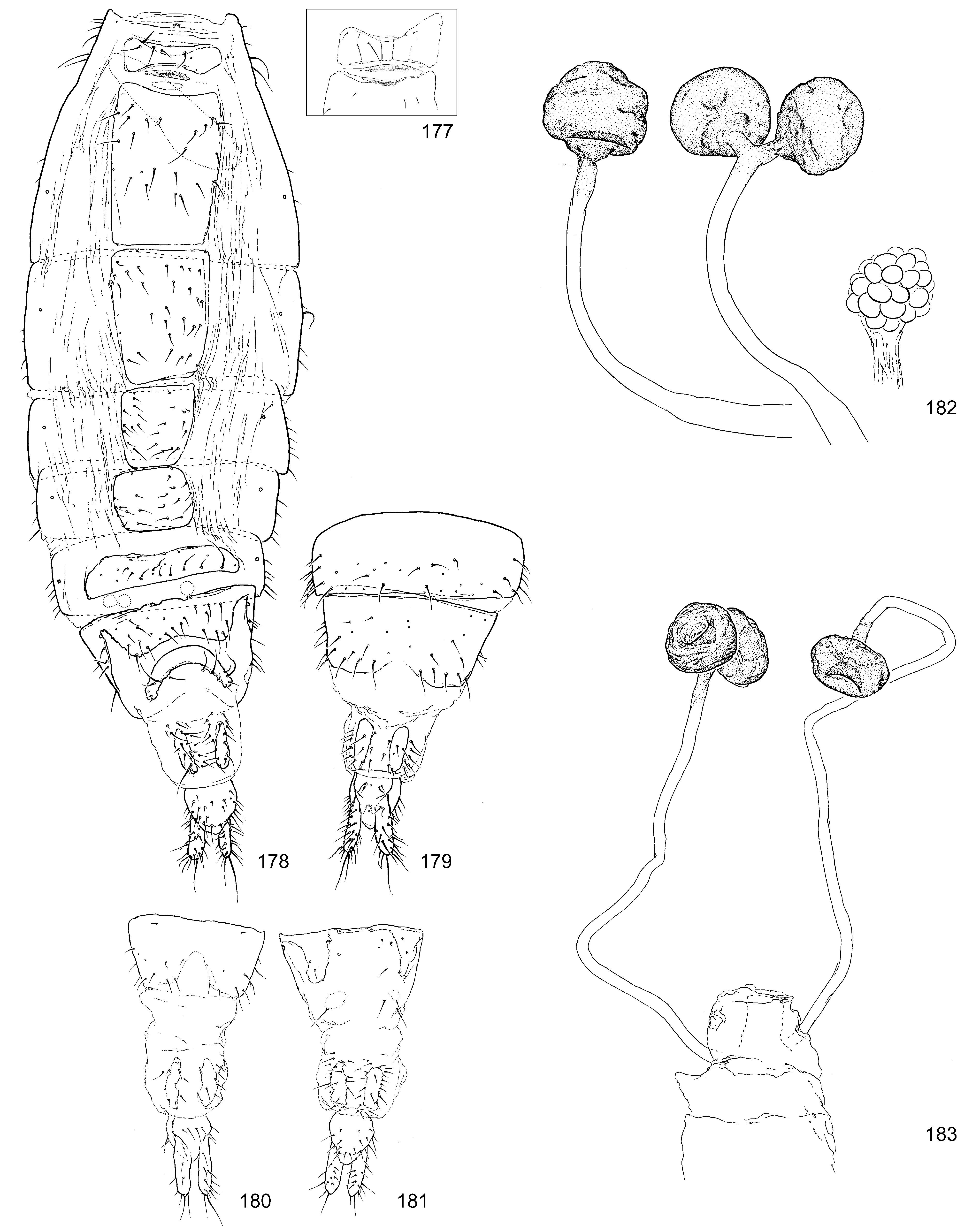

Female abdomen. ( Figs 177–190 View FIGURES 177–183 View FIGURES 184–190 ) Terminalia relatively short and broad, not telescoped or forming oviscape, but sometimes more abruptly narrowed past segment 6; sometimes deflexed apically. S7 and T7 usually united anterolaterally; S7 sometimes transversely divided with posterior section sometimes lost, or sometimes posterior and (less frquently) anterior section also divided longitudinally. T8 and S8 longitudinally divided, but sometimes halves of sclerite secondarily joined medially; S2–5 rarely with similar division. S10 short, variable in shape, setose. Cerci separate, variable in shape, with several setae. Non-sclerotized internal organs described in Kumar (1978) and Kumar & Nutsugah (1976). Usually three spermathecae on two long ducts, with one pair joined near apex of single duct; Diopsinae sometimes only one spermatheca on each duct; shape of spermatheca “egg-shaped” to more elongate and subcylindrical, with base often narrower and surface often rough, tuberculate, or with subconical projections; apex sometimes invaginated or duct telescoped within spermatheca; surface sometimes also with “[t]iny satellites, linked with fine filaments” ( Feijen, 1989); spermatheca and apex of duct pigmented. Ventral receptacle short with apical clustering of small sacs, sometimes forming dome confluent with genital chamber. Diopsinae with vaginal sclerite confluent with genital chamber wall, usually circular or ovate, and sometimes accompanied by additional separate distal semicircular band.

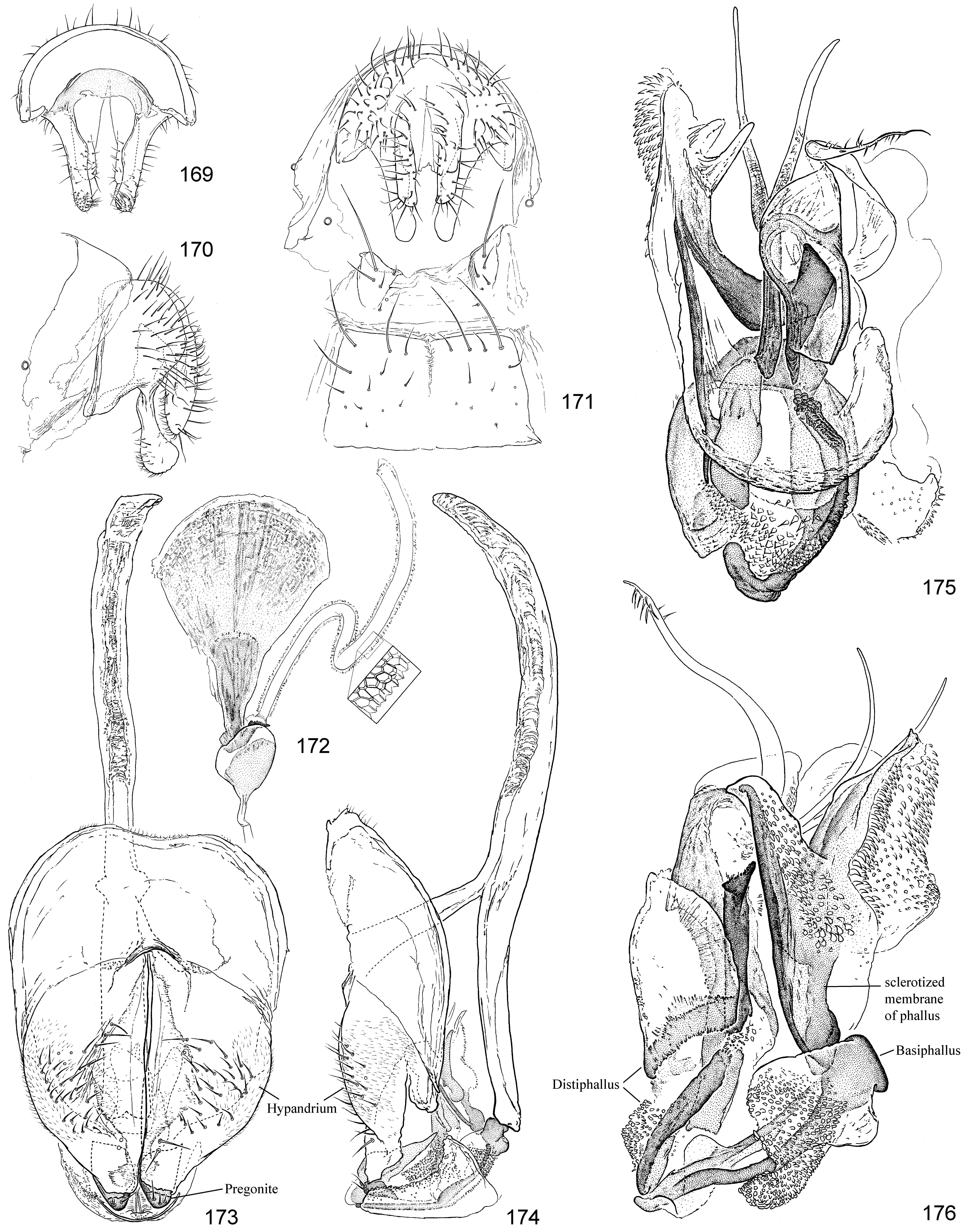

Male abdomen. ( Figs 153–176 View FIGURES 153–159 View FIGURES 160–168 View FIGURES 169–176 ) Sternites entire, with S6 divided longitudinally and moderately to highly reduced in Diopsinae; S5 also uncommonly divided. Tergite 6 usually short with setae along posterior margin. Sternite 7 band-like and fused to S8; Centrioncinae with ventral band reaching right margin of S8, which is large, dome-like and symmetrical ( Figs 153–154 View FIGURES 153–159 ). Epandrium and surstyli well-developed; surstyli converging and fused to epandrium in Diopsinae ( Fig. 160 View FIGURES 160–168 ); Centrioncinae with surstylus narrow and trilobed, with long spines on anterodistal branch and short tubercles on posterodistal branch ( Figs 155–157 View FIGURES 153–159 ). Cerci narrow, separate; Centrioncinae with cerci large and L-shaped, covering enlarged ventral lobe of subepandrial sclerite ( Fig. 157 View FIGURES 153–159 ). Subepandrial sclerite usually simple, curved and plate-like ( Figs 162 View FIGURES 160–168 , 169 View FIGURES 169–176 ), but Centrioncinae with one pair of enlarged setose ventral lobes with broad, setose distal section ( Fig. 156 View FIGURES 153–159 ). Phallapodeme narrow distally and with medial extension fused to hypandrium. Hypandrium broad and plate-like laterally with distal and medial setae (medial setae on lobe in Centrioncinae, surrounding by weakened/broken section of hypandrium; Fig. 158 View FIGURES 153–159 ); “arms” of hypandrium short, not fused dorsally. In Centrioncinae, pregonite large, setose and lobate ( Figs 158–159 View FIGURES 153–159 ); in Diopsinae, pregonite narrow, linear; apex setose in Diopsini ( Figs 173–174 View FIGURES 169–176 ), with long, parallel tubercles in Sphyracephala ( Figs 165–166 View FIGURES 160–168 ). Postgonite absent. Basiphallus U-shaped, elongate, sometimes asymmetrical. Epiphallus sometimes present as minutely spinulose membrane. Distiphallus with flat basal section (forked or longitudinally divided in Diopsinae) and complex, forked apical section with one pair of membranous “wings” (spinulose in Diopsinae) and dark medial sclerite; membranous region from base of basiphallus to posterior surface of distiphallus variably sclerotized, often thick and complex, acting as a supporting structure ( Figs 168 View FIGURES 160–168 , 176 View FIGURES 169–176 ). Ejaculatory apodeme with linear or fan-shaped blade with darker base sometimes with subbasal “flagellum” ( Fig. 172 View FIGURES 169–176 ); sperm pump with cup- or ring-shaped sclerotization.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.