Rhagomys septentrionalis, Moreno Cárdenas & Tinoco & Albuja & Patterson, 2021

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jmammal/gyaa104 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A13EAF98-6C6E-438E-B2BF-4458FC1AD80B |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10668550 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/6CA8F0DC-BE22-4BE2-B03E-A3BE26FC254E |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:6CA8F0DC-BE22-4BE2-B03E-A3BE26FC254E |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Rhagomys septentrionalis |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Rhagomys septentrionalis , sp. nov.

Northern Rhagomys View in CoL

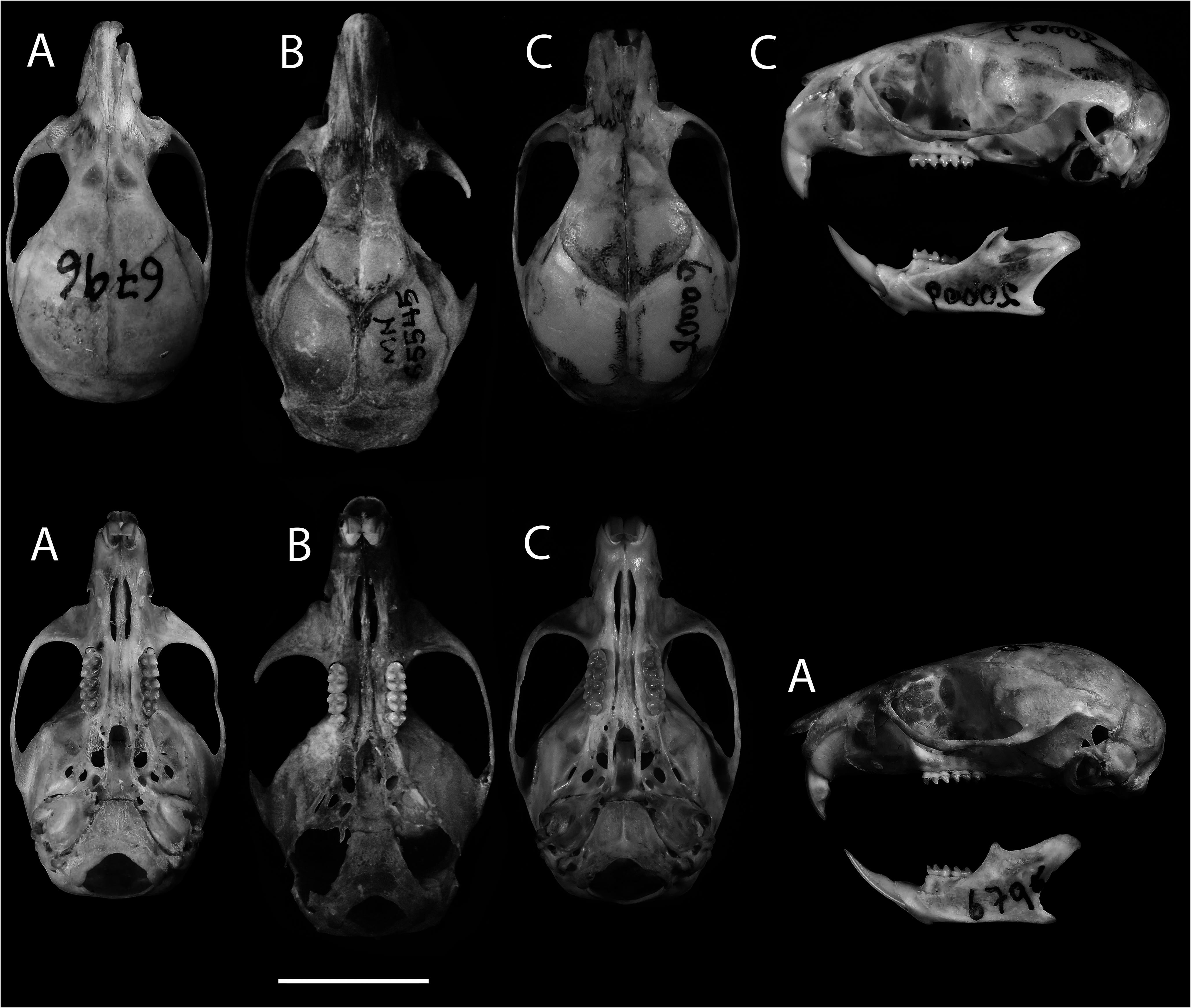

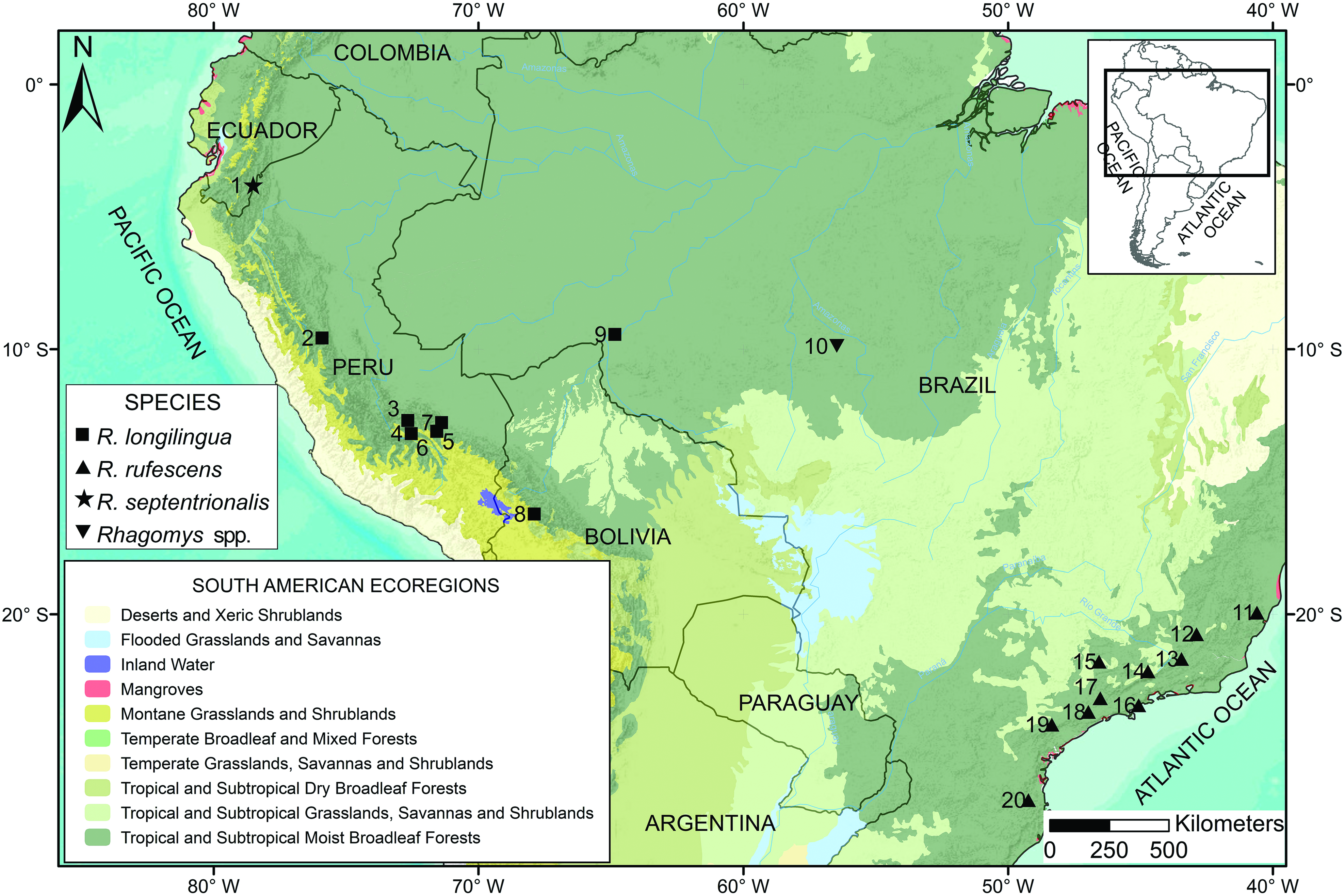

Figs. 3−6 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig ; Table 1 View Table 1

Holotype. —An adult specimen, with all molars fully erupted at occlusal level, age class 2, sex unknown, prepared as dry skin, cranium and skeleton in good condition and deposited in the Mammalogy collection of the Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas de la Escuela Politécnica Nacional del Ecuador ( MEPN 10898 ). The holotype was collected by Ramiro Barriga on 6 November 2008 and prepared by Luis Albuja .

Type locality. — Ecuador, Zamora-Chinchipe province, Refugio de Vida Silvestre “El Zarza,” on the shore of the Río Blanco, 2 km N San Antonio (town), 03°48 ′ 13 ʺ S, 78°30 ′ 10 ʺ W, 1,442 m elevation, in the western foothills of the Cordillera del Cóndor ( Fig. 1 View Fig ) GoogleMaps .

Etymology. —The name “ septentrionalis ” comes from Latin meaning “of the north,” referring to the distribution of this species at the northern edge of the generic range.

Diagnosis. —Orange-colored mouse with spiny hairs on the back and rump to the base of the tail, without a black ring of skin around the eyes, and without superciliary vibrissae. Hair color on the tail is the same above and below.

The interorbital region is narrow and hourglass-shaped, with slightly marked supraorbital cristae. The postorbital process is short and inconspicuous ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The ectotympanics are large and round. The lower extreme of the squamosal hamular process reaches halfway up the mastoid. A conspicuous transverse canal is located at the sides of the cranium at the base of the pterygoid. The incisive foramina are long and narrow. The M1 presents a procingulum interrupted by a prominent anterolabial conule that occupies virtually the entire leading margin of M1, and the anterolingual conule is almost inconspicuous, marked by a minute anteromedian flexus. The anteroloph of the M1 is directly connected to the posterior section of the anterolabial conule, without an intermediate connection (anterolophule). The anterior mure of M1 and M2 are directly connected to the anterior margin of the protocone and surpass the posterior margin of the protocone to shape the median mure, while the paracones of M1 and M2 do not connect with the median mure, joining the paraflexus with the mesoflexus. The m3 does not have an ectostylid on its labial margin.

Description. —The description is based solely on the holotype ( MEPN 10898). This specimen closely resembles the descriptions of other Rhagomys ( Thomas 1886, 1917; Luna and Patterson 2003; Percequillo et al. 2004) and is a mouse of medium size and weight (total length 190 mm and weight 23 g). The holotype has orange spiny pelage, small ears, flattened dental structure, without folds, with simple, conical cusps like those of the rodent genus Abrawayaomys , with a round nail embedded in the hallux of the foot, with large callous plantar pads.

External characters. —The body is covered by short hairs DFL = 9 mm ( Table 1 View Table 1 ), a bit longer on the nape and shoulders (10 mm) and completely covering the skin. The texture is spiny on the dorsum and belly, over which latter the pelage is shorter (5 mm). The color on the dorsum, the forehead, back, and sides of body, is Raw Umber (color 23). The muzzle, cheeks, rostrum, and post-auricular patches are paler and Cinnamon (color 39). The lower jaw, the insides of the arms and manus are Clay (color 123 B); a paler color extends towards the belly and continues inside the hind legs and towards the backs of the feet. There are two types of hair on the body: on the dorsum, the hair is flattened and coarse, like spines, with a transparent keel in the middle, thick edges, as in Neacomys , but with a smaller hair diameter than the spiny hair of Neacomys . The spiny nature of hair is less pronounced on the shoulders, neck, and head. This condition is probably a function of the specimen’s age. The color along the edges of the spiny hair of R. septentrionalis is Neutral Dark Grey (color 83) along the middle and Blackish Gray neutral (color 82) at the apex, where the transparent keel disappears. The color tone of the spiny hairs on the nape and head is darker.

The second class of hair is thin and curly, with the basal portion Dark Grey neutral color and the apical third of the hair colored in Spectrum Orange (color 17) that resembles the general tone over the dorsum and sides of the body.

The belly with spiny hair, Cream (color 54) at the base and Clay apically from the belly extending to the anus and insides of the legs. The thin hair on the belly is Clay throughout its length and denser than the spiny hair.

The ears are small, covered inside by inconspicuous silverplated hair, fringed by tiny orangish hairs; externally, the pinnae are blackish, clothed in short brown hairs, becoming whitish at the base.

The eye margins do not have a blackish ring of skin. The longer mystacial vibrissae (Weksler and Percequillo 2011) extend 1 cm beyond the ear. No superciliary vibrissa is present, but an elongated genal vibrissa exceeds the margins of the ear, there are two interramal vibrissae, and one very small submental vibrissa at the edge of the lower lip.

The tail is longer than the head-and-body, covered by hairs similar in color to the rump for about 10 mm from its base and with a little tuft, 4 mm long, at its tip. The scales on the tail form rings around it. The color on the upper part of the tail is Vandyke Brown (color 221) and it is covered by short spiny hairs 1.2 mm long of the same color that exceed by 2.5 times the length of the scales in the tail, and are projected in triads from the edge of each scale. The hair in the middle is a little longer than the ones at either side of each scale. Below, the color is paler and for about a third of its length, the tone is Draft (color 27), covered by shorter hairs than those dorsally, fading into Pale Pinkish Buff (color 121D) along the length and tip of each hair. Along the apical third of the tail, the ventral section is as dark as the upper section.

The characters of the manus are described from the dry skin. The digits match the description of Luna and Patterson (2003). They are long with round fingertips, with a deep depression in the front end of the apical pads. More proximally, the digits have parallel and transverse grooves, almost invisible as seen on the dry skin. There also are three interdigital pads, one hypothenar, and one thenar (Luna and Patterson 2003), all of them well-defined. The D3 and D4 are almost the same length, the D4 slightly longer. There is a vestigial thumb with a minute nail. The nails of the manus are very small (1 mm length), slightly surpassing the fingertips; the ungual claws are embedded in the fingertips, so they can scarcely be seen in ventral view, where one appreciates that they are concave and sharp at the tips. All the hairs at the base of the claws are transparent and greatly surpass the tips of the claws. Along their dorsal surface, the skin of the hands is covered by short transparent hairs.

The pes is blackish dorsally with five digits entirely covered by short orange hairs (Clay colored). As on the manus, pedal digits show transverse ventral grooves and rounded fingertips with apical indentations. The D2, D3, and D4, are the longest toes; the D5 exceeds by more than half the second phalanx of D4. The hallux is medium-sized, with a length of 3.25 mm from the union of the first phalanx with the metatarsus, surpassing the lower edge of the second interdigital pad to reach the middle of the first phalanx of D2. The hallux shows a flattened nail on the fingertip that does not appear as a claw. The pes has six plantar pads: four are interdigital, one hypothenar, and one thenar. The hypothenar is smaller than the thenar pad and is located beside the fourth interdigital pad. The claws on the pedal digits are longer than those of the manus, with an approximate length of 1.9 mm (except on the hallux) and width of 0.40 mm (on D3); on all of these, the claws surpass the tips in ventral view. The hair at the base of the claws is transparent, as on the manus, and slightly surpasses the tips.

The soles of the pes are completely naked. However, hair along the margins completely covers the calcaneum region.

Skull. —The skull is broad and robust. The rostrum is long, narrow, and ends in a tip. The interorbital region is narrow, with a broad, rounded braincase. The zygomatic arches are parallelsided, with a conspicuous jugal bone. The anterior margin of the upper incisors does not reach the anterior margin of the nasals, nor do their tips exceed the anterior edge of the premaxillary. The nasolacrimal capsule joins the premaxillary with an opening to the posterior proximal to the anterior margin of the zygomatic plate. The nasals are elongate, wider anteriorly but narrowed posteriorly to form a “ V ” shape at their frontal suture. The posterior projection of the premaxillary exceeds by 1 mm the hindmost extent of the nasal bones. The zygomatic notch is shallow ( Fig. 3 View Fig ).

The zygomatic arches converge anteriorly. The zygomatic plate is moderately wide, low, extending 5.31 mm from the maxillary root of the zygomatic arch to the lower part of the plate. The anterior border of the plate is slightly tilted posteriorly and is totally posterior to the nasolacrimal capsule. The antorbital bridge of the zygomatic maxillary root stands at almost the same height as the tip of the nasals in lateral view. The first maxillary molar (M1) lies at a level just behind the posterior edge of the zygomatic plate.

The interorbital region is wide posteriorly (on the frontals) and convergent anteriorly (towards the lacrimals), appearing hourglass-shaped ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The specimen has faint but noticeable supraorbital cristae. The interparietal is wide and does not contact the squamosal bone. The length of the supraoccipitalparietal suture is longer than the occipito-squamosal suture. The anterior section of the squamosal bone presents a faint postorbital process, visible from a dorsal view of the cranium as a small protrusion inside the orbit.

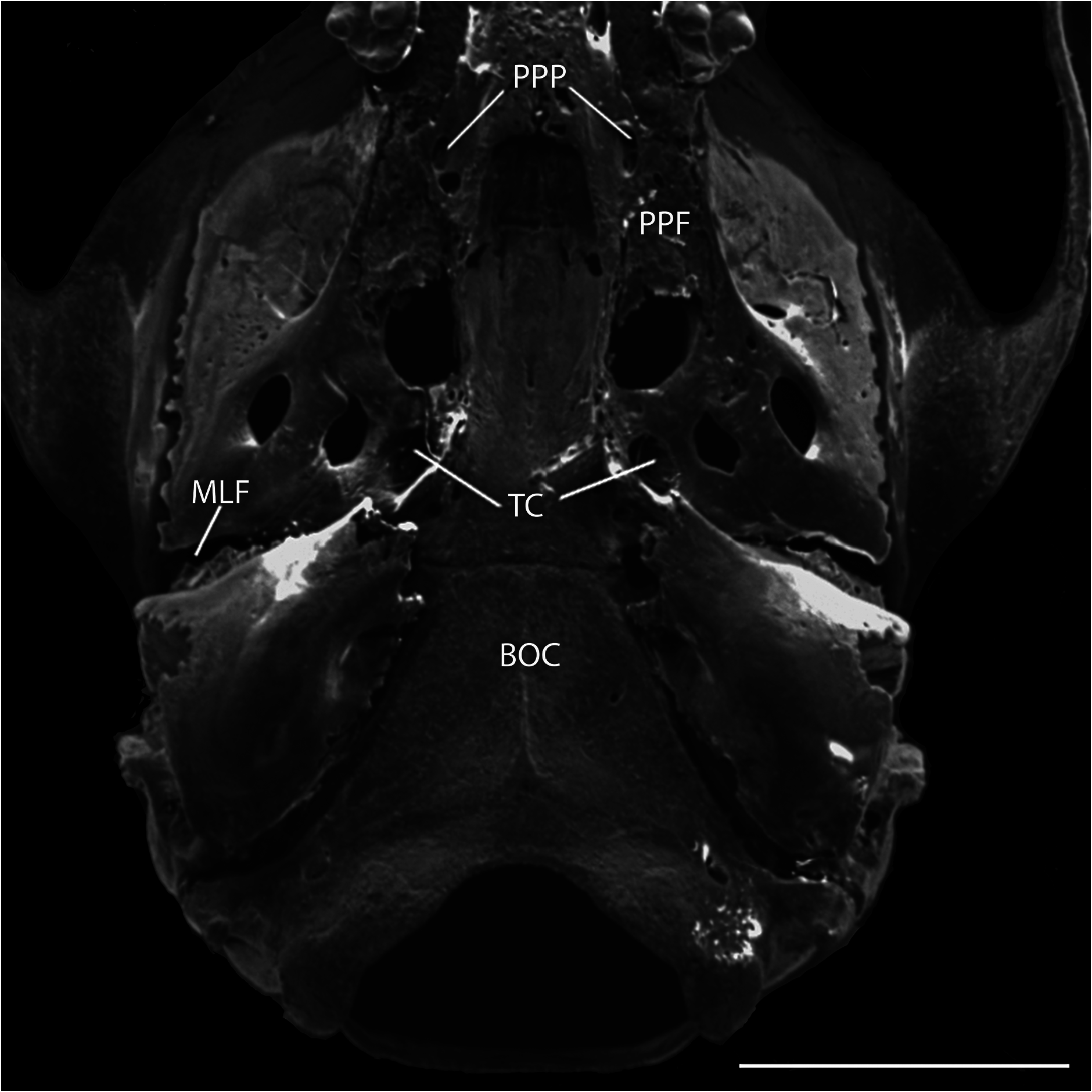

The alisphenoid strut is broad and partially hides the opening of the alisphenoid canal from lateral view. The foramen ovale accessorius is completely visible ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The pattern of the carotid circulation resembles pattern 3 ( Voss 1988): lacking squamosal-alisphenoidal grooves or a sphenofrontal foramen; in the ear region, without a stapedial foramen, the periotic is hidden by the ectotympanic. The auditory bullae have well-developed carotid canals. Under the basisphenoid, a conspicuous transverse canal is situated at the level of the hamular pterygoid processes ( Fig. 4 View Fig ). The posterior region of alisphenoid shows a marked posterior opening of the alisphenoid canal in oval shape, with a small middle lacerate foramen with a laterally widened shape ( Fig. 4 View Fig ). There is a groove for the infraorbital branch of stapedial artery in the posterior part of the pterygoid plate; this groove is long, running from the posterior opening of the alisphenoid canal into the middle lacerate foramen.

The foramen ovale is similar in size to the posterior opening of the alisphenoidal canal and is visible in ventral view, because the edge of the pterygoid plate located between the posterior opening of the alisphenoidal canal and the foramen ovale is flattened in the cranium of this genus and does not project outside it, as happens in other cricetids in which the foramen ovale is hidden ventrally by the edge of the pterygoid plate.

The parapterygoid fossa is shallow and wide ( Fig. 4 View Fig ), with a prominent pit. These pits are round, with thin and irregular edges. The tegmen tympani or petrosal overlaps slightly the posterior suspensory process of the squamosal bone. The squamosal hamular process is wide and widens posteriorly to contact the mastoid and the ectotympanic. The mastoid fenestra lies between the mastoid periotic suture and the exoccipital and is less conspicuous and elongated, located at the left side of the cranium. Another fenestra is located between the mastoid and the exoccipital over the paraoccipital process. The ectotympanic ends near the pterygoid hamulars in a short, wide eustachian tube. The carotid canal is small and situated near the end of the eustachian tube. The basioccipital surface is almost flat, and there is a small but noticeable median crista that extends from the anteroventral edge of the magnum foramen towards the anterior edge of the basioccipital.

The subsquamosal fenestra and the postglenoid foramen are well-developed. These foramina are shaped like parentheses, so they narrow and converge at the anterior and posterior margins. The premaxillary and maxillary suture ventrally bisects the incisive foramen. The septum of the incisive foramen occupies almost half of its total length. The masseteric tubercle is a small projection in the maxillary, anterior to M1.

The palate is large, with the posterior margin that extends beyond the M3 roughly the length of that tooth (0.52 mm). The posterior margin of the palate ends at a wide mesopterygoid fossa without a medial process or spine ( Fig. 4 View Fig ). The suture of the anterior part of the palatine with the maxillary lies at the level of the M1 hypocone, and its posterior sutures with the pterygoids lies at half the height of the parapterygoid fossa. The posterolateral palatal pits are very conspicuous in a defined fossa, containing two foramina at the right side and one at the left of the palatine ( Fig. 4 View Fig ). The posterolateral palatal pits surpass the posterior edge of the palatine and extend for a sixth part of its length into the mesopterygoid foramen. The dental maxillary rows are sub-parallel because they converge towards the anterior. The anterior margin of the mesopterygoid foramen presents square angles. In the roof of the mesopterygoid foramen, two small sphenopalatine vacuities are visible in the leading edges of the basisphenoids. The pterygoid hamular processes were slightly damaged during preparation, but they appear to diverge slightly towards the eustachian tubes.

Mandible. —The angular process is short and sharp ( Fig. 5 View Fig ). The coronoid process is short, with an anterior border straight up, that does not reach the level of articular condyle. The articular condyle is enlarged, narrow, oriented behind and with the same thickness as the neck of the condyloid. The angular notch of the mandible is shallow. The capsular process of the lower incisor is very conspicuous and visible in dorsal view. In lateral view, it is located at the midpoint of the mandibular notch. There is a conspicuous lower masseteric crest, whose anterior extent surpasses the anterior cingulum of m1. There is a wide and deep retromolar fossa, whose anterior margin reaches the entoconid of the m2, and its posterior margin is at the level of the posterior part of the articular process. There also is a well-developed digastric apophysis at the mandibular symphysis.

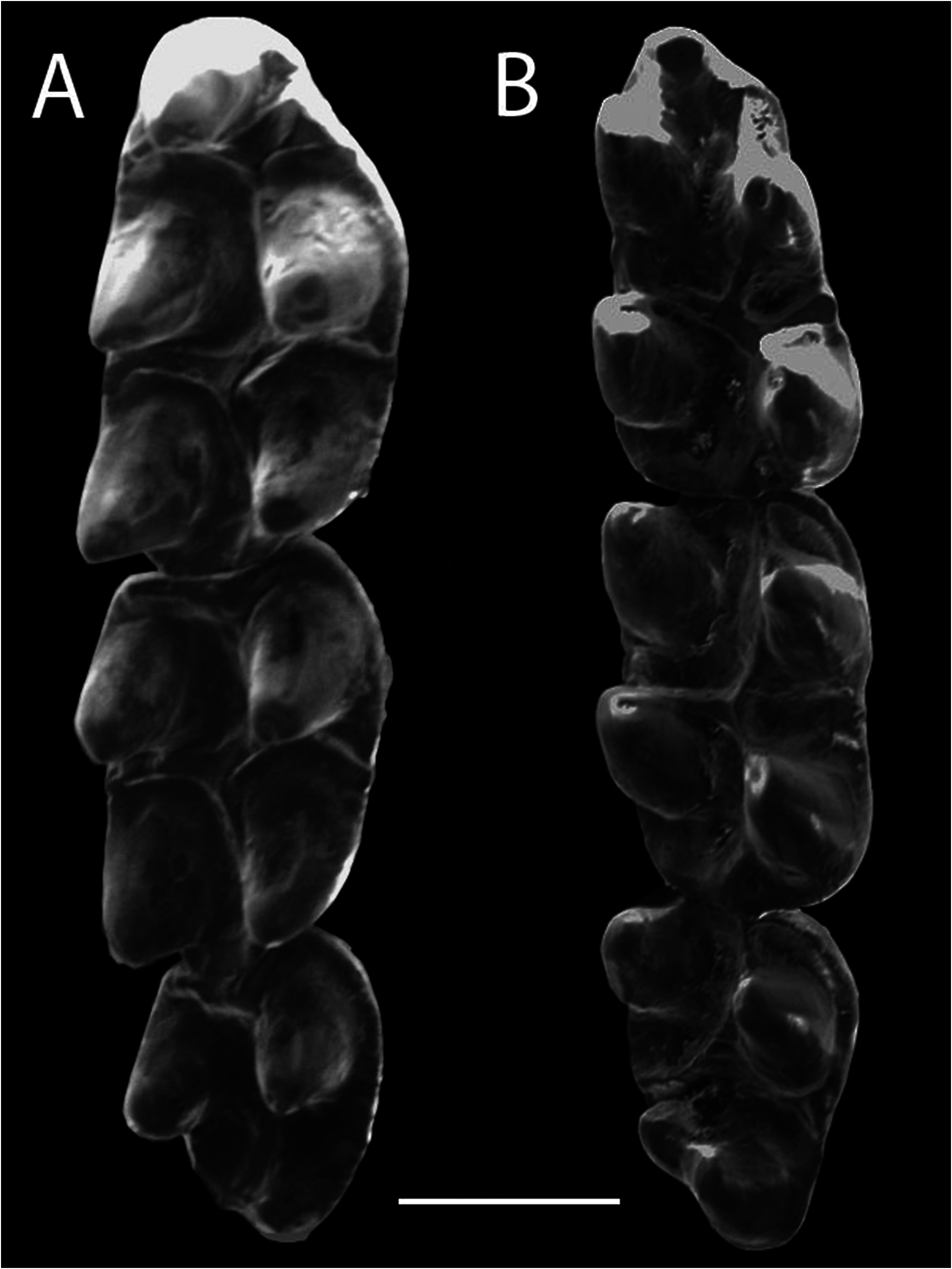

Dentition. —The incisors are orthodont and narrow, with a fine, straight fissure in the dentine that is visible in posterior view as a black line on the incisors. The molars are pentalophodont, containing a paracone, protocone, metacone, hypocone, and mesoloph ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). The molars are low crowned, with cusps similar to tubercles (bunodont) that are very noticeable. These cusps are narrow and oriented posteriorly on the upper molars; the flexi and flexids are wide and well-defined. The paracone and metacone of the M1 and M2 are not at the same level with the protocone and hypocone but rather are staggered behind them. The same occurs with the conids of the lower molars, where the protoconid and hypoconid are situated posterior to the metaconid and entoconid, respectively. M1 is longer than M2, M2 is longer than wide, and M3 is rounded and half the length of M2. The paraflexus and mesoflexus completely encircle the paracone, because posterior to the paracone, the paraflexus connects with the mesoflexus, but there is no connection between the paracone and the median mure ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). The metacone is almost completely encircled by the metaflexus on M1 and M2.

The anteromedial flexus is present but short and shallow, located between a well-developed anterolabial conule and a minute, inconspicuous anterolingual conule ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). There is no internal projection of the enamel on the anterolabial conule of M1 designated by Luna and Patterson (2003) as the anteromedial crista. The anteroloph adheres to the posterior part of the anterolabial conule. A small crista extends from the posterior part of the anterolingual conule to connect it with the anterior mure. On the M1 and M2, the anterior mure connects directly with the anterior margin of the protocone; on the protocone’s posterior margin, it shapes the median mure. This mure extends medially towards the mesoloph on both anterior molars. The anterolabial conule does not give any sign of an anterolophule or of a connection with the anteroloph, because the anterolabial conule and anteroloph are fused and reach the labial edge of M1, where there is a conspicuous parastyle. The paracones of M1 and M2 do not have an additional connection with the median mure and are isolated from the other molar cones ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). The anteroloph of M2 is fused labially with the anterior edge of the paracone that extends postero-lingually to form a shallow protoflexus. A posteroflexus is lacking on M1 and M2, but the posteroloph joins with the posterior part of the metacone. A long, conspicuous mesoloph is fused with a small mesostyle on M1 and M2. M3 is rounded and has an anterior mure that extends from the posterior edge of the anteroloph towards the anterior margin of the protocone and turns obliquely as a median mure from the posterior margin of the protocone to the posterior portion of the molar, where there is a structure that may be the hypocone. There also is a paraflexus anterior to the paracone.

The procingulum of m1 presents the anterolingual conulid in the most anterior part of m1 that extends near the labial end of the procingulum ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). The m1 lacks an anteromedial flexid. However, a protolophid is present and it ends in a conspicuous protostylid. The anterior murid is conspicuous and connects to the anterior margin of the protoconid, continuing from the posterior margin of the protoconid towards the median muride. There is no anterolophid. The mesolophid is fused with a conspicuous mesostylid at the lingual edge. The entolophulid is fused with the trailing edge of the mesolophid. The posterolophid is long and reaches the posterior margin of the lingual cingulum.

The entoflexid and posteroflexid join to encircle the entoconid almost completely. The mesolophid on m2 is fused with the anterior edge of the entoconid at its lingual end. The median murid connects with the anterior margin of the hypoconid. There is a short posterocrista (Luna and Patterson 2003) that extends from the posterior part of the hypoconid, reaching the posterior margin of m2.

The m2 and m3 differ in size and shape. The m3 is subtriangular with well-defined protoconid and metaconid; posteriorly, the hypoconid and entoconid are fused at their internal margins. The m2 and m3 present a mesolophid that on m2 joins with the entoconid, but on m3 does not reach the entoconid and continues towards the lingual cingulum of the molar ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). In addition, the hypoconid of m3 does not connect with the mesolophid to form a median murid and a posterocrista is lacking on the posterior cingulum of m3.

Comparisons.— Rhagomys species are very similar in color, but the spiny coat of Rhagomys in the Andean foothills of Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, clearly distinguishes them from R. rufescens , which has a soft coat.

Comparisonwith R.longilingua . ―Rhagomysseptentrionalis is similar in size to R. longilingua ( Table 1 View Table 1 ). Both species have spine-like hairs on the dorsum and belly. In both species, the length of the tail (individuals between ages 2 and 4) is almost the same as the length of the head-and-body, uniform in color, and covered with short hairs that are longer on the tip.

The cranium of R. septentrionalis is rounded but is more oval in R. longilingua . The orbital region of R. septentrionalis is narrower anteriorly, as the maxillary root of the zygomatic arch hardly projects laterally, whereas in R. longilingua the anterior part of the orbit is wider ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The interorbital region in R. longilingua is wide and converges anteriorly into a “ V ” shape, with its narrowest point just behind the lacrimal bones. In contrast, in R. septentrionalis , the interorbital region is narrowest more posteriorly and flares anteriorly towards the lacrimals, so that the region appears hourglass-shaped. Rhagomys septentrionalis has inconspicuous supraorbital cristae, unlike those of R. longilingua , which are evident even in young specimens ( Villalpando et al. 2006). The postorbital process in R. septentrionalis is shorter and less conspicuous than in R. longilingua . Relative to skull length, R. septentrionalis has a larger interparietal bone than R. longilingua viewed dorsally. The rostrum in R. septentrionalis is narrower than in R. longilingua , especially at the anterior nasal-premaxillary suture. Relative to cranial length, the rostrum is slightly longer in R. septentrionalis (28%) than in R. longilingua (26%). The diastema in R. septentrionalis also is enlarged, with the procingulum of M1 located just behind the posterior margin of the zygomatic plate, whereas in R. longilingua , the procingulum of M1 lies far behind the posterior margin of the zygomatic plate (by the length of M2). Its incisive foramen is enlarged ( IFL = 4.2 mm) relative to that of R. longilingua ( IFL = 3.76 mm; Table 1 View Table 1 ). However, its palate is shorter than in R. longilingua because the incisive foramina reach posteriorly to the procingulum of M1 ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The parapterygoid fossae in R. septentrionalis are shallow and the fontanelles are rounded, while in R. longilingua the parapterygoid fossae are deeper and the fontanelles are ovate. The posterior opening of the alisphenoid canal lies beside the oval foramen, because the posterior part of the pterygoid plate, which separates these two foramina in ventral view in all Rhagomys , is not as wide in R. septentrionalis as in R. longilingua . The auditory bulla in R. septentrionalis is larger than in R. longilingua , but its eustachian tubes are shorter, even compared with young specimens of R. longilingua ( Villalpando et al. 2006) . The eustachian tubes are wide and short and located near the hamular process of the pterygoids.

In lateral view, the cranium of R. septentrionalis exhibits a smaller postglenoid foramen than even young specimens of R. longilingua ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The supraorbital crest in R. longilingua can be seen in lateral view of the cranium (including on young specimens), especially along the frontals where it arises on its anterior edge, but in R. septentrionalis this crest is not seen in side view.

The maxillary cusps in the molars of R. septentrionalis are oriented posteriorly, while the cusps of the lower molars are oriented forward more than in R. longilingua . The maxillary toothrow in R. septentrionalis is similar in size to that of R. longilingua , although the toothrows of R. longilingua slightly converge anteriorly ( Fig. 3 View Fig ).

The M1 of R. septentrionalis is long (2.03 mm) as in R. longilingua , but its procingulum comprises a large anterolabial conule that occupies the entire anterior margin of M1 ( Fig. 6 View Fig ) and an inconspicuous anterolingual conule, making the anteromedial flexus minute. On the other hand, all Peruvian and Bolivian specimens of R. longilingua have a well-developed anterolingual conule and a deep anteromedial flexus (Luna and Patterson 2003; Villalpando et al. 2006; Medina et al. 2017) although this flexus is smaller in the recently reported Brazilian specimen ( Percequillo et al. 2017). The anterolabial conule of M 1 in R. septentrionalis lacks an anteromedial crista, which is present in Peruvian specimens but lacking in the Bolivian specimen of R. longilingua ( Villalpando et al. 2006) . The anteroloph of M 1 in R. septentrionalis is attached directly to the rear of the anterolabial conule, whereas in R. longilingua the two are connected via a secondary connection, the anterolophule (Luna and Patterson 2003). In R. septentrionalis , the anterior mure of M1 and M2 is directly connected to the anterior margin of the protocone and exits the posterior margin of the protocone to form the median mure; the paracone of both molars lacks a connection with the median mure, while in R. longilingua the paracone and protocone of M1 and M2 join the median mure by small connections. A posteroflexus is lacking on the M1 and M2 of R. septentrionalis because the posteroloph joins the metacone labially, whereas Luna and Patterson (2003) described a small, shallow posteroflexus on M1 and M2.

In R. septentrionalis , the hypoconid and the entoconid are fused along the posterior margin of m3 ( Fig. 6 View Fig ), whereas a median murid separates the hypoconid and entoconid in R. longilingua . In R. septentrionalis , a mesolophid is evident on m3 that joins neither with the entoconid nor with the hypoconid and does not form a median murid. However, R. longilingua has a median murid and a very conspicuous posterocrista on m3.

Comparison with R. rufescens . — Rhagomys septentrionalis also resembles R. rufescens in size ( Table 1 View Table 1 ), but some adult specimens of R. rufescens exceed the size apparently reached by R. septentrionalis . Tail length is similar in R. septentrionalis and R. rufescens . Externally, the main difference between these two species is that R. rufescens lacks flattened spines in its pelage; rather, R. rufescens has soft and dense pelage (Luna and Patterson 2003; Percequillo et al. 2004), whereas R. septentrionalis has spiny hairs covering its dorsum and belly.

Both species have an enlarged cranium with a longer, narrower rostrum than in R. longilingua . However, the cranium in R. rufescens is bigger ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The interorbital region of both species is narrowed at a midpoint, but the interorbital region in R. septentrionalis is more sharply narrowed, whereas R. rufescens has an interorbital region shaped like a parenthesis and is more smoothly tapered (Pavan and Leite 2011). Both species have nasals that extend far beyond the premaxillary, and are slightly downturned at the anterior end. The zygomatic notch is deeper and wider in adult R. rufescens than in R. septentrionalis ; although the zygomatic notch is tapered in younger specimens of R. rufescens ( Percequillo et al. 2004; Passamani et al. 2011), it remains more conspicuous than in R. septentrionalis . Both species have a faint supraorbital crista along the interorbital region, squarely angled but not overhanging the margin ( Percequillo et al. 2004). The interparietal in R. rufescens is larger in the sagittal plane than in the transversal one as in R. septentrionalis , and in neither species does it reach the squamosal bone at its lateral margins.

The incisive foramen in R. rufescens is short (57%) relative to diastema length ( Percequillo et al. 2004), whereas in R. septentrionalis , the incisive foramen is longer (64%), and its posterior margin reaches nearly the level of the M1 cingulum. The region of the masseteric tubercle in R. septentrionalis is smooth, whereas in R. rufescens , small fossae are evident near the anterior root of M1 ( Percequillo et al. 2004). The zygomatic plate in R. septentrionalis is narrower than in R. rufescens ( ZPB = 2.86 mm versus 3.3 mm; Table 1 View Table 1 ), and in both species the anterior edge of the zygomatic plate is straight and lacks a zygomatic spine. However, in R. rufescens , the zygomatic plate forms an acute angle over its antero-dorsal margin. The length of the orbital fossa in R. septentrionalis is shorter ( LOF = 9.35 mm) than in R. rufescens ( LOF = 10 mm, SD = 0.39, range = 9.34–10.65), resembling specimens of R. rufescens at age 1 ( Table 1 View Table 1 ). The mesopterygoid foramen of R. rufescens is narrow ( Percequillo et al. 2004; Pavan and Leite 2011), whereas the mesopterygoid foramen in R. septentrionalis is wide and square-shaped at its anterior end. Both species present sphenopalatine vacuities, but those in R. septentrionalis are smaller. The basioccipital of R. septentrionalis is wider posteriorly than in R. rufescens ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). The auditory bullae of R. septentrionalis are wider and longer with shorter Eustachian tubes. The occipital condyles of R. rufescens are farther from the upper molars in lateral view of cranium ( Percequillo et al. 2004) than the ones in R. septentrionalis . The squamosal hamular process in R. septentrionalis is narrow as in R. rufescens ; however, in R. septentrionalis , it is longer and contacts with the mastoid at medium height.

On the mandible, the mental foramen of both R.septentrionalis and R. longilingua lies at a level about midway beneath m1; in R. rufescens , the mental foramen is located ventral to the anterior margin of m1 ( Fig. 5 View Fig ). The upper masseteric crest in R. rufescens evident in figures 10–12 of Pavan and Leite (2011) is more conspicuous and straighter than in R. septentrionalis , where it is less conspicuous and more bowed. The capsular process of the lower incisor in R. septentrionalis is located at the middle of the angular notch of the mandible, whereas in R. rufescens this process is located in the posterior third portion of the angular notch.

The dental maxillary cusps of R. septentrionalis are narrower than in R. rufescens . The labial cusps of the upper molars are slightly posterior to the lingual cusps in R. septentrionalis ( Fig. 6 View Fig ), whereas in R. rufescens , the labial and lingual cusps are located at the same level ( Percequillo et al. 2004).

The anteromedial flexus of R. septentrionalis in M1 is short and shallow, whereas in R. rufescens it is well-defined and deep ( Percequillo et al. 2004). The anterolingual conule in R. septentrionalis is smaller than the anterolabial conule ( Fig. 6 View Fig ), whereas in R. rufescens the anterolingual conule is similar in size to the anterolabial conule. The m1 of R. septentrionalis presents the metaconid close to the posterior margin of the anterolingual conulid that reduces and narrows the metaflexid, while in R. rufescens , the metaflexid is wider and more conspicuous. In the m1 and m2 of R. septentrionalis , the mesolophid adheres to the former margin of the entoconid, and does not allow the entoflexid to reach the lingual side, whereas in R. rufescens the mesolophid of m2 clearly separates the mesoflexid and the entoflexid ( Percequillo et al. 2017). In both species, the m3 is very similar with a reduced entoconid that is joined with the hypoconid, so that the posterior margin of m3 is more triangular than square (as in R. longilingua ; Luna and Patterson 2003).

Natural history. —The type locality of R. septentrionalis lies in “El Zarza” (Wildlife Shelter “El Zarza”), located in Canton Yantzatza of Zamora-Chinchipe Province. This is a well preserved forest. Owing to peculiarities of local topography, humidity, and the atmosphere, the vegetation is characteristic of medium-height forests with canopy gaps. Some trees are covered by epiphytes. The forest in the area of San Antonio is very dense especially for the shrubby vegetation at the margins of Rio Blanco. The forest is periodically flooded in some areas close to the river. Great quantities of mosses and herbs cover the ground. According to Aguirre et al. (2013), El Zarza is part of the Evergreen foothill forest ecosystem of the mountain ranges of the Cóndor-Kutukú, characterized by dense vegetation. The representative trees species are: Aniba muca , Brosimum utile , Cecropia marginalis , Celtis schippii , Chimarrhis glabriflora , and Elaphoglossum latifolium (Aguirre et al. 2013) . This vegetation is characteristic of very humid forests located in the eastern foothills of the Andes in Zamora Chinchipe province (Aguirre et al. 2013), where many streams descend gentle slopes between 1,400 and 1,800 m. The specimen of R. septentrionalis was captured in one such stream in the “El Zarza,” opportunistically scooped out of the water with a hand fishing net. The habitat of the R. septentrionalis specimen was similar to the very humid habitats where R. longilingua was found in central and southern Peru, northern Bolivia, and Brazilian Amazonia ( Percequillo et al. 2017).

Other species of small mammals that MEPN surveys documented in the area of San Antonio are Didelphis marsupialis , Marmosops murina , Monodelphis adusta , Saccopteryx sp. , Anoura caudifer , Artibeus sp. , Carollia brevicauda , Myotis sp. , Molossus sp. , Euryoryzomys sp. , Nephelomys albigularis , and Hadrosciurus igniventris .

Remarks. —Our morphological and genetic results confidently recover the new mouse as a species of Rhagomys . The genetic results corroborate the position of that genus in the tribe Thomasomyini proposed by D´Elía et al. (2006) and Pacheco et al. (2015). Other members of the tribe include Aepeomys and Chilomys (both endemic to the Northern Andes), Thomasomys (endemic to the Northern and Central Andes), and the widespread genus Rhipidomys , found across most of the Neotropics. The discovery of Rhagomys septentrionalis extends the range of that genus 700 km northward from the records in central Peru at Santa Rita Alta, Huánuco ( Medina et al. 2017) and 1,400 km westward from the record near Jirau, Rondônia ( Percequillo et al. 2017). Despite the paucity of records for Rhagomys , its geographic range now rivals that of all 44 species of Thomasomys (mammaldiversity.org) in geographic spread and biome occupation.

The sigmodontine rodents appear to have diversified in the late Miocene (9.3–6 million years ago (mya); Vilela et al. 2013; Parada et al. 2015). From their origination 11.4–8.5 mya, sigmodontines began to colonize South America 7.96–6.49 mya (Steppan and Schenk 2017). The Thomasomyini radiated in northern South America and quickly colonized the Andean zones and adapted to Andean ecosystems ( Maestri et al. 2019); the divergence of Rhagomys from other thomasomyines was dated at 6.5 million years by Schenk and Steppan (2018). Subsequently, Rhagomys has acquired many remarkable apomorphies (Luna and Patterson 2003; Percequillo et al. 2011a), including its elongate facial vibrissae, a nail on the hallux, transverse grooves on digits tipped by crescent-shaped depressions with short, embedded claws, and its molar cusp arrangement.

The new record of Rhagomys in Ecuador calls attention to the need for additional field surveys and taxonomic studies on rodents and other mammal groups. The Ecuadorian Andes are one of the most diverse areas for Thomasomyini , as well as for other tribes of Sigmodontinae (Maestri and Patterson 2016). In addition, the Ecuadorean Andes are a locus of high endemism and represent the continent’s “hottest” hotspot for rodent species with highly restricted geographic ranges (Maestri and Patterson 2016).

The natural history and ecology of R. septentrionalis is uncertain because only a single specimen is known, thus there is a lack of knowledge about most of its habits. Its locomotory habits likely resemble those of other species of Rhagomys , because it shares the same characteristics of the hands, feet, and tail (Luna and Patterson 2003; Percequillo et al. 2011b). This genus has short, straight claws—not curved ones—and a narrow metatarsus, as in the arboreal-climbing rodents Rhipidomys and Oecomys ( Rivas-Rodríguez et al. 2010) . Its short legs and bulging finger tips without claws resemble those of some genera of arboreal marsupials and primates. Rhagomys also has been captured in traps placed on vegetation a meter or two aboveground (Luna and Patterson 2003). However, all these Rhagomys species are likely to have much broader ecological habits and ranges than are currently documented ( Percequillo et al. 2011a), simply because we have so few records of them.

Rhagomys septentrionalis was found living in a very mesic habitat crossed by many streams, raising the possibility that it might move in rivers. The holotype was actually captured in the middle of a river, although it lacks structures (interdigital webbing or stiff hairs along the margins of the pes or on the tail) typically present in semiaquatic rodents ( Voss 1988; Kerbis Peterhans and Patterson 1995). Although it could be natatorial, it seems equally probable that MEPN 10898 might have fallen into the river accidentally, while climbing on riparian vegetation. Only additional observations can clarify its natural history .

| V |

Royal British Columbia Museum - Herbarium |

| ZPB |

Herbarium Soutpansbergensis |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.